Manco

While he attacked Cuzco, Manco entrusted Quizo Yupanqui and his captains Ilia Tupac and Puyu Vilca with the conquest of the central highlands. Another general, Tiso, had already been fomenting rebellion among the natives of the Jauja area with some success. At the first hint of trouble, the Spaniards had despatched a punitive expedition of some sixty men, mostly foot-soldiers, under one Diego Pizarro. These operated in the Jauja area while Tiso vanished into the eastern jungles and reported back to Manco at Ollantaytambo.

Governor Francisco Pizarro first heard about the attack on Cuzco on 4 May, in his new capital Los Reyes, or Lima. He at once feared for his brothers and the other Spaniards isolated in Cuzco, and began organising relief expeditions. He sent thirty men over the mountains to Jauja, under Captain Francisco Morgovejo de Quiñones, one of the two alcaldes of Lima. This force marched inland in mid-May, with orders to proceed along the royal road and garrison the strategic crossroads of Vilcashuaman. It travelled through peaceful country beyond Jauja and as far as Parcos, an important tambo above the gorge of the Mantaro. Morgovejo de Quiñones learned here that the natives had killed five Spaniards travelling towards Cuzco. His reprisals were swift and vicious. He gathered twenty-four chiefs and elders of Parcos into a thatched building and burned them all alive. He hoped in this way to intimidate the natives so that he could proceed unmolested to a rendezvous with Diego Pizarro at Huamanga.

Pizarro also despatched another force of seventy horse under his relative Gonzalo de Tapia. This contingent took the middle route, descending the coast for some 120 miles and then climbing inland past Huaitará, which is still graced by Inca ruins, to cross the Andes at 15,000 feet and strike the royal road north of Huamanga. Tapia’s force crossed the desolate puna of Huaitará but was caught by the Indians in a defile on the upper Pampas river -‘ one of the worst passes in the land’. It had run into Quizo Yupanqui’s new army marching north from Cuzco.

These various parties of marching Spaniards were tempting prey to the rebellious natives. The superiority of Spanish horses and weapons was nullified by the Andean topography: for these central Andes are one of the most vertical places on earth, an endless succession of crumbling precipices, savage mountain torrents, landslides and giddy descents. Here, at last, the natives had a really effective natural ally. ‘Their strategy’, wrote Agustín de Zárate, ‘was to allow the Spaniards to enter a deep, narrow gorge, seize the entrance and exit with a great mass of Indians, and then hurl down such a quantity of rocks and boulders from the hillsides that they killed them all, almost without coming to grips with them.’ Using this tactic, the natives now succeeded in annihilating Tapia’s seventy horse – almost as many mounted men as were defending Cuzco. The few survivors were sent as prisoners to Manco Inca.

Quizo continued northwards and soon met Diego Pizarro’s sixty men, who were marching down the Mantaro towards Huamanga. The Indians repeated their successful use of topography. Quizo trapped and exterminated Diego Pizarro’s entire force near the same Parcos where Morgovejo had burned the chiefs a few weeks before. News of these great victories was sent back to Manco, together with some Spanish post, weapons and clothing, the heads of many dead invaders,’ and two live Spaniards, one Negro and four horses’. The messengers reached the Inca soon after he had heard the news of the loss of Sacsahuaman at the end of May. His son Titu Cusi remembered the great rejoicings over the victory. To show his appreciation, Manco sent his victorious general ‘ a coya wife of his own lineage, who was most beautiful, and some litters in which he could travel with more authority’.

When Pizarro learned of the rebellion of Manco Inca, the prince he had crowned and in whom he had such confidence, he resorted to the familiar tactic of finding a rival puppet Inca. He chose a royal prince, probably Cusi-Rimac, who was with him in Lima. This man was given a hasty coronation and dispatched towards Jauja, protected by thirty horse under Captain Alonso de Gaete. Shortly afterwards pro-Spanish native yanaconas started bringing alarming rumours of the fate of the other expeditions. Pizarro decided that Gaete’s thirty men were too vulnerable. He therefore sent a further thirty foot-soldiers under Francisco de Godoy, the other mayor of Lima for the year 1536, and they left in mid-July.

The victorious Quizo Yupanqui was also marching on Jauja. Most of the original citizens of Jauja had descended to the coast to settle in Pizarro’s new capital Lima, but there were still a number of Christians living in the former Inca city. According to Martin de Murua, these Spaniards were too arrogant to post sentries or make preparations to defend themselves. ‘ Quizo Yupanqui arrived one morning at daybreak. He came upon the Spaniards so suddenly that the first they knew was that they were surrounded on all sides. They did not even have time to dress, for they were still in bed. In this tumult they positioned themselves in an usno [temple platform] they had there as a fortress with any weapons they found most readily to hand. Anyone can imagine the confusion: for they never thought that the Indians would have the courage to attack them…. The fighting lasted from the morning when the Indians arrived until the hour of vespers … and the Indians killed them all, and their horses and Negro servants.’

As the thirty foot-soldiers under Godoy approached Jauja they met the pathetic figure of Gaete’s half-brother Cervantes de Maculas fleeing with a broken leg on a pack-mule. This man and one other Spaniard were the only survivors of Gaete’s force, which was reported killed by its own Indian auxiliaries. The puppet Inca apparently succeeded in crossing to the native side in the heat of the battle: a brother called Cusi-Rimache was later prominent in Manco’s camp. Francisco de Godoy decided not to risk sharing the fate of Gaete’s, Diego Pizarro’s and Tapia’s men. He turned around and rode back into Lima in early August ‘with his tail between his legs, to give Pizarro the bad news’.

Quizo had now succeeded in annihilating almost all the Spaniards between Cuzco and the sea, including the inhabitants of Jauja and many travellers and encomenderos along the Jauja-Cuzco road. He had also defeated three well-armed relief forces of Spanish cavalry – over 160 men. The only Spanish force still at large in the central Andes was the thirty men under Morgovejo de Quinones. These continued down the Mantaro after massacring the elders of Parcos. At one crossing they were trapped by hordes of native warriors, who occupied both banks of the deep canyon. Night fell, and Morgovejo’s men camped by the river bank. They left camp-fires burning and were able to slip away in the darkness. There was another skirmish in a defile before the expedition managed to reach the tambo of Huamanga. The men could not rest for long. Throughout the following day native forces massed on the slopes around the tambo, and Morgovejo’s men saw a cluster of handsome litters that evidently contained the general Quizo Yupanqui and his staff. But the Spaniards again escaped under cover of darkness. They climbed the hills behind the tambo, and even took their weeping native women and yanaconas, who feared the reprisals of their compatriots if their European masters were annihilated.

The exhausted expedition now attempted to ride back across the Andes to the coast. There were many days of marching and fighting around the ravines of the upper Pampas river. The Spaniards finally reached the last defile that separated them from the sanctuary of the coastal plain. But the local Indians had prepared another ambush. As the column entered the pass the air was filled with the echoing shouts of the warriors. Most of the Spaniards were trapped. The path was too narrow for them to fight, and they were caught in a barrage of boulders. Captain Morgovejo leaped from his exhausted horse and mounted the croup of another. But this animal was struck by a rock: both riders were thrown and Morgovejo’s thigh was shattered. The Spanish captain fought on for hours before he and his native attendant were killed. Four more of his men were killed at the passage of a river, but the shattered remnants reached the coast road and returned to Lima. They were almost the only survivors of some two hundred men sent into the sierra to relieve Cuzco.

It was now some months since Francisco Pizarro had heard from his brothers in Cuzco, and he feared that they must be dead. ‘The Governor was deeply worried by the course of events. Four of his commanders had now been killed, with almost two hundred men and as many horses.’ When the rebellion broke out, Pizarro at once tried to consolidate his forces in Peru. Alonso de Alvarado was recalled from the conquest of the Chachapoyas, beyond Cajamarca in north-eastern Peru; he eventually reached Lima with thirty horse and fifty foot. Gonzalo de Olmos brought some men and seventy horse from Puerto Viejo on the Ecuadorean coast; and Garcilaso de la Vega, the father of the historian, abandoned an attempt to colonise the Bay of San Mateo and took eighty men back to Lima. Pizarro’s half-brother Francisco Martin de Alcántara was sent along the coastal plain to warn Spanish settlers of the danger and to gather them back to Lima.

But Pizarro could look for help beyond Peru. His invasion of the country was only one tentacle of Spanish colonisation of the Americas. Pizarro hoped at first to crush the rebellion from his own resources: he sent Juan de Panes to Panama in July to buy arms and horses with 11,000 marks of his personal fortune that were lodged there. But he soon realised that the rebellion was too serious and decided to appeal for help to all the Spanish governors in the Americas. In his desperation he even wrote on 9 July to Pedro de Alvarado, Governor of Guatemala, the man who had attempted to invade Quito and been humiliated and bought off by Pizarro only eighteen months previously. Pizarro now wrote him an eloquent plea: ‘The Inca has the city of Cuzco besieged, and for five months I have heard nothing about the Spaniards in it. The country is so badly damaged that no native chiefs now serve us, and they have won many victories against us. It causes me such great sorrow that it is consuming my entire life.’ Diego de Ayala took this letter to Guatemala and sailed on to Nicaragua, where he eventually recruited many good men. At the same time Licenciate Castañeda passed through Panama on the way to Spain, and Pascual de Andagoya wrote to the Emperor from Panama at the end of July that ‘ the Lord of Cuzco and of the entire country has rebelled’. ‘The rebellion has spread from province to province and they are all coming out in rebellion simultaneously. Rebellious chiefs have already arrived forty leagues from Lima. The Governor [Pizarro] is asking for help and will be given everything possible from here.’

News of the Peruvian revolt gradually reached Spain itself. As early as February 1536 the aged Bishop Berlanga of Tierra Firme, who had just returned from a royal mission to Peru, reported to King Charles that Governor Pizarro was allowing his conquistadores to violate the ordinances for good treatment of the natives. He also reported ominously that ‘the Governors have exploited the Inca, Lord of Cuzco, and so have any other Spaniards who wished to’. In April, Licenciate Gaspar de Espinosa wrote from Panama telling the King of the first killings of isolated Spaniards in the Cuzco area. But news of the full siege of Cuzco did not arrive across the Atlantic until late August. The first reports of the rising said that ‘Hernando Pizarro caused this rebellion, for it is said that he tortured the chief cacique so that he would give him gold and silver.’

Manco Inca, delighted by Quizo’s victories, ordered him to descend on Lima ‘and destroy it, leaving no single house upright, and killing any Spaniards he found’ except for Pizarro himself. But Quizo wanted to ensure that his rear would be secure. He therefore spent July recruiting Jaujas, Huancas and Yauyos, trying to persuade these anti-Inca tribes to join his rebellion. Quizo was understandably reluctant to engage Spaniards on the level ground and unfamiliar surroundings of the coastal plain unless he had overwhelming strength. He succeeded in recruiting a large force from the tribes along the western slopes of the Andes, and eventually brought his great colourful army down to the lowest range of Andean foothills, within sight of the hazy waters of the Pacific. The first news of them was brought by Diego de Aguero. He ‘arrived in flight at Los Reyes, reported that the Indians were all under arms and had tried to set fire to him in their villages. A great army of them was approaching. The news deeply terrified the city, all the more so because of the small number of Spaniards who were in it.’ Governor Pizarro sent seventy horse under Pedro de Lerma to try to prevent the Indians moving down on to the plain. A sharp engagement took place, in which many Indians lost their lives, ‘one Spanish horseman was killed and many others wounded, and Pedro de Lerma had his teeth broken’. The native army continued its advance on the European city.

‘When the Governor saw this multitude of enemy he had no doubt whatsoever that our side was completely finished.’ Quizo’s warriors advanced across the plain and some even entered the outlying houses of the city. But ‘the cavalry were hidden in ambush, and at the appropriate moment they charged out, killing and lancing a great number of them until they retreated and climbed into some hills. A strong guard was mounted by night, with the cavalry patrolling around the city’. Quizo now moved his army on to the Cerro de San Cristobal, a steep sugarloaf hill just across the Rimac river from the heart of Lima. This hill is encrusted today with a dusty slum, a tawny wart of poverty rearing above the modern city. Another hill was occupied by troops from the valleys of the Atavillos to the north-east of Lima – men better accustomed to the low, sea-level altitude and heavy atmosphere of Lima than their companions from the highland tribes. Other native warriors occupied hills between Lima and its port, a few miles away at Callao. The Spanish settlement was thus surrounded and almost severed from its communications with the sea.

The Spaniards were desperately anxious to dislodge Quizo’s men from San Cristóbal. Cavalry were useless against its steep flanks. A bold night attack, normally successful ‘since Indians are very cowardly at night’, seemed suicidal against so steep a hill occupied by so many enemy. Nevertheless, five days were spent preparing for such an attack. ‘It was agreed to build a shield of planks as protection against rocks. But when this was made it proved impossible to carry it.’

There was the usual confusion of loyalties during the siege. ‘Many Indian servants of the Spaniards went out to eat and live with the enemy and even to fight against their masters, but returned at night to sleep in the city.’ Francisco Pizarro suspected an Indian concubine of treachery. Atahualpa’s sister Azarpay, whom ‘he had in his lodging’, was accused by Pizarro’s chief love Doña Inés of encouraging the besiegers. ‘So, without further consideration, he ordered that she be garrotted, and killed her when he could have embarked her on a ship and sent her into exile.’ There were, on the other hand, ‘some friendly Indians in the city who fought very well. Because of them the horses were spared from over-exertion, which they could not otherwise have endured.’

On the sixth day of the investiture of Lima, the native commander decided to end the stalemate with a full-blooded attack on the city. This was the critical moment of the rebellion, the attempt to drive the Spanish invaders back into the Pacific. Quizo Yupanqui ‘determined to force an entry into the city and capture it or perish in the attempt. He addressed his forces as follows: “I intend to enter the town today and kill all the Spaniards in it…. Any who accompany me must go on the understanding that if I die all will die, and if I flee all will flee.” The Indian commanders and leaders swore to do as he said.’ The native leader also promised his men enjoyment of the handful of Spanish women then in Lima – probably not more than fourteen women including Francisca Pizarro’s three godmothers. ‘We will take their wives, marry them ourselves and produce a race of warriors.’ The Spaniards had been busily creating the same race of mestizos ever since they set foot in Peru – but their unions with native women were not for eugenic purposes.

Quizo Yupanqui planned a simultaneous attack on Lima from three sides. He himself advanced from the hills to the east; the tribes of the Atavillos and north-central sierra marched in along the coastal road from Pachacamac. The most determined attack was that of the Incas under Quizo himself. It possessed splendour and reckless bravery, the magnificent futility of the French at Agincourt, the British at Balaclava or the Confederates at Gettysburg. ‘The entire native army began to move with a vast array of banners, from which the Spaniards recognised their determination. Governor Pizarro ordered all the cavalry to form into two squadrons. He placed one squadron under his command in ambush in one street, and the other squadron in another. The enemy were by now advancing across the open plain by the river. They were magnificent men, for all had been hand-picked. The general was at their head wielding a lance. He crossed both branches of the river in his litter.

‘As the enemy were starting to enter the streets of the city and some of their men were moving along the tops of the walls, the cavalry charged out and attacked with great determination. Since the ground was flat they routed them instantly. The general was left there, dead, and so were forty commanders and other chiefs alongside him. It was almost as if our men had specially selected them. But they were killed because they were marching at the head of their men and therefore withstood the first shock of the attack. The Spaniards continued to kill and wound Indians as far as the foot of the hill of San Cristóbal, at which point they encountered a very strong resistance from the Indian redoubt.’† Manco Inca had lost his most successful general, the gallant Quizo Yupanqui.

With the slaughter of so many of their leaders, the fight went out of the Indians. The more agile Spaniards were planning a night attack on San Cristóbal, but the native army melted away into the mountains before the venture was attempted. The highland Indians were uncomfortable in the hot, close atmosphere of the coast: their lungs are specially evolved to live at high altitude. They despaired of driving Pizarro from his coastal city: the superiority of the Spanish horsemen was too crushing on a flat, open plain at sea level. The coastal tribes conspicuously failed to join in the highland revolt against the invaders, and the Spaniards had a number of coastal curacas in protective custody in Lima.

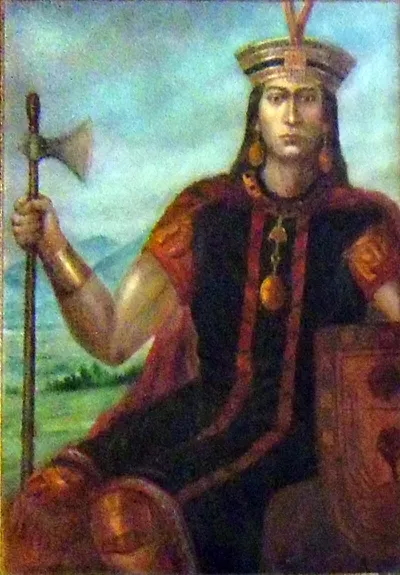

Who was Quizo Yupanqui?

Quizo Yupanqui was an Incan general for Manco during the Great Inca Rebellion.

What was Quizo Yupanqui’s military strategy?

Quizo Yupanqui used different military strategies depending on the engagement. In general, Quizo was successful at using stealth and surprise to surrounding the enemy.