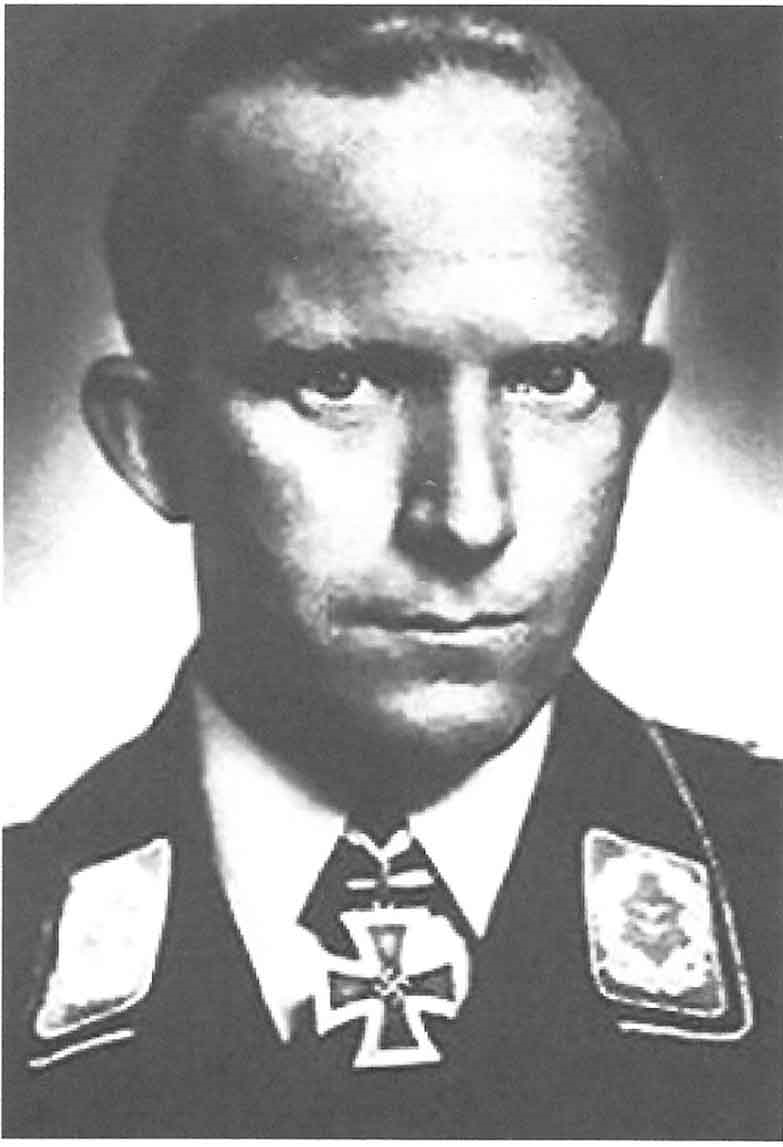

Generalleutnant Gustav Wilke, Commander of the 5th Parachute Division in Normandy. Although one of the Luftwaffe’s newest and least capable formations, the 5th Parachute Division would acquit itself well at Hill 122 and Monte Castre. Its accomplishments and sacrifices, however, have never been truly recognised

5th Parachute Division

Among the ranks of the 3rd Parachute Division were the cadre and filler personnel for a second airborne formation that was being formed at the time and would be engaged heavily in Normandy, the 5th Parachute Division. To train this new formation, instructors and weapons were taken from the 3rd Parachute Division, undermining Generalleutnant Schimpf’s efforts to man and train his own unit. The 5th Parachute Division was formed in March 1944 and sent to Brittany in May. The division was commanded by Generalleutnant Gustav Wilke. Born in Deutsch-Eylau, West Prussia, on 6 March 1898, Wilke had entered the German Imperial Army in 1916, serving as an officer candidate in the 4th Grenadier Regiment and ending the war as a second lieutenant before leaving service in 1920. During the post-war period he served in various grenadier, infantry, and even artillery regiments. On 1 October 1935 Wilke transferred to the Luftwaffe, where he served in a series of increasingly noteworthy positions. During the campaigns of 1940 he was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross and he continued to rise through the officer ranks, commanding Luftwaffe Infantry Regiment Wilke in 1942 as a colonel on the Eastern Front and then the newly formed 1st Luftwaffe Field Division in 1943, which he led into battle in the Lake Ilmen area of Russia. Promoted to generalmajor, he was appointed commander of the 2nd Parachute Division shortly after it was transferred to the Eastern Front. The division was almost wiped out over the next several months in the heavy fighting that ensued and by January 1944 was down to 3,200 paratroopers. Nonetheless, it continued to hold its 13-mile long sector. In April 1944, Wilke was given command of the 5th Parachute Division. Like most of his Fallschirmjäger contemporaries, Gustav Wilke was an extremely knowledgeable and combat-hardened veteran.

The 5th Parachute Division’s organisation included three parachute infantry regiments. The 13th Parachute Regiment was commanded by forty-five-year-old Major Wolf Werner Graf von der Schulenburg, a Knight’s Cross recipient and First World War veteran. Schulenburg had participated in the airborne invasions of Holland and Crete, served two tours on the Eastern Front with the 1st Parachute Division’s Parachute Regiment 1, and fought with the same division at Monte Cassino in Italy. Major Herbert Noster led the 14th Parachute Regiment. A former policeman, Noster was a veteran of the General Göring Regiment, which later became the 1st Parachute Regiment. He fought with the 2nd Parachute Regiment in the airborne invasion of Holland 1940 and was taken prisoner during the battle for Ypernburg airfield, which initially went very badly for the Germans. Noster was one of many paratroopers, including officers, captured by the Dutch Army and transported to Great Britain. Promoted to major in absentia, he was released from British captivity in November 1943, due to his heavy war wounds, in a POW exchange between Great Britain and Germany. The 15th Parachute Regiment was led by thirty-seven-year-old Major Kurt Gröschke. Gröschke was a recipient of the German Cross in Gold and a future recipient of the Knight’s Cross. The regimental commanders in the 5th Parachute Division were as strong as in any formation in the German Seventh Army, including the 3rd Parachute Division.

Each of the three parachute infantry regiments consisted of three battalions, with each made up of three companies and a heavy weapons company (81mm mortars and Panzerschreck or Panzerfausts). In addition, each regiment possessed two heavy weapons companies, one with 120mm mortars or light artillery pieces (75mm mountain or light guns) and another with anti-tank guns (75mm AT guns and Panzerschreck or Panzerfausts). For support, the division had the 5th Parachute Artillery Regiment (with three artillery battalions); 5th Parachute Anti-Aircraft Battalion (with one battery of 88mm guns); 5th Parachute Anti-Tank Battalion (with three batteries of 75mm guns); 5th Parachute Engineer Battalion (with four companies); and 5th Parachute Signals Battalion. The 5th Parachute Engineer Battalion was commanded by twenty-five-year-old Major Gerhart Mertens, a recipient of the German Cross in Gold and future recipient of the Knight’s Cross and Wound Badge in Gold. There was no shortage of exceptional leaders in Wilke’s division.

The 5th Parachute Division had an authorised strength of 17,455 men but reported a ration strength of 12,836 men on 22 May 1944. This made the division the only German formation of its size in Normandy to have the strength of what the British termed a ‘second-quality’ infantry division (12,000 soldiers). In comparison, four other infantry divisions in Normandy were much weaker than what the Germans termed ‘defensive infantry divisions’ (10,000 men). The soldiers of the 5th Parachute Division were a mixed lot, with many apparently poorly trained and equipped. ‘Actually, you could divide the men into two groups,’ observed Obergefreiter Karl Max Wietzorek, a member of the division. ‘The first lot had been stationed in France for a year and did not believe in an invasion, only in the Thousand-Year Reich and their beloved Führer, Adolf Hitler. The second group consisted of all the men who had come from the Russian front; mostly sick soldiers, in shoddy patched uniforms, not interested in any more fighting.’ Wietzorek was one of the latter. While he had been in hospital recovering from wounds, his unit had been annihilated at Zhitomir on the Kiev road and in February 1944 he was sent back to the Channel coast near St-Malo. ‘I was a parachute corporal, wearer of the black wound badge, wearer of the Iron Cross second class, wearer of the parachute badge,’ he recounted, ‘in other words, a “fully-licensed” parachute soldier, completely entitled to my ration of six cigarettes a week, plus some inferior food, just like my comrades.’

In addition to the questionable quality of his troops, Wilke noted that many of his units were seriously short of equipment, especially artillery and anti-tank guns. And like most Wehrmacht formations in France, the 5th Parachute Division was short of motor vehicles, possessing only 30 per cent of the number authorised. ‘The 5th Parachute Division was of little combat value,’ assessed Major Friedrich August Freiher von der Heydte, somewhat harshly. Perhaps his unforgiving evaluation was simply a case of an ‘old’ veteran paratrooper taking the measure of a new generation of Fallschirmjäger that simply couldn’t measure up to the giants that came before them. Von der Heydte, a veteran first-generation Fallschirmjager, was the commander of 2nd Parachute Division’s 6th Parachute Regiment in Normandy. Evaluating the 5th Parachute Division on the eve of the Allied invasion, he wrote: ‘Less than 10 per cent of the men had jump training [and] at most 20 per cent of officers had infantry training and combat experience’. ‘Armament and equipment [were] incomplete; only 50 per cent of authorised number of machine guns; one regiment without helmets, no heavy anti-tank weapons; not motorised.’ The highly opinionated von der Heydte rated the officers of the division as ‘extremely poor’, noting that they consisted mainly of Luftwaffe ground personnel without any infantry experience or tactical knowledge. And he recorded that the 5th Parachute Division’s commander, Generalleutnant Gustav Wilke, ‘was regarded by all the parachute troops as an ignoramus.’ Later, a battalion commander of the 6th Parachute Regiment ordered to take command of a regiment of the 5th Parachute Division would report to the First Parachute Army that command and control of the division ‘were absolutely shocking’. Finally, the division had had only 60 per cent of its authorised manpower, 25 per cent of its light weapons, 23 per cent of its heavy weapons, and only 9 per cent of its motor vehicles. The 5th Parachute Division was the last Fallschirmjager division to receive jump training.

‘The Seventh Army was aware of the extremely low combat efficiency of 5th Parachute Division,’ recorded Generalleutnant Max Pemsel, the Army Chief of Staff. As a result of its low readiness, the German Seventh Army planned on committing the parachute infantry regiments of the 5th Parachute Division piecemeal to the fighting in Normandy once the invasion began and then only for a short period of time in order to ensure that each formation fed into the battle was as trained and combat ready as possible. The intense and prolonged nature of the battle, however, along with heavy losses and the shortage of replacements would doom Wilke’s Fallschirmjäger to remain on the front lines, where they would suffer calamitous attrition.

At the time of the Allied invasion, the 5th Parachute Division sector was located between St-Michel and St-Brieuc. The division command post was located 4km south-south-east of the Dinan, with the 13th Parachute Regiment located at Plancoet, 6km to the north-west; the 14th Parachute Regiment located at Amballe, 19km to the east-south-west; and the 15th Parachute Regiment located 13km to the north-east of Dinan. The division staff, supply and administrative units were located at Evran to the south-south-east. ‘The mission assigned was to prevent enemy groups from landing,’ recorded General Wilke. ‘To repulse by attack any group that had perhaps landed; to hold the positions to the last man.’ Under II Parachute Corps, one of the Luftwaffe’s best and most capable combat ready formations in June 1944, the 3rd Parachute Division, would be paired with one of its newest and least capable, the 5th Parachute Division. This was a situation all too familiar to German commanders in France on the eve of the Allied invasion.

2nd Parachute Division

Elements of two other German parachute divisions, the 2nd and 6th, would also fight in Normandy. The 2nd Parachute Division in France was commanded by General der Fallschirmtruppe Hermann Bernhard Ramcke, a living legend, even among Hitler’s elite paratroopers. He had distinguished himself during the First World War as a member of the Marine Assault Battalion and was commissioned an officer. After the end of the First World War he transferred to the Army, fought with the Freikorps, and was accepted into the Reichswehr, the armed forces of the German Weimar Republic, where he commanded an infantry company and then a battalion. In July 1940 he transferred to the Luftwaffe’s 7th Flieger Division (which would later become the 1st Parachute Division). Ramcke earned his parachutist–rifleman badge and joined the ranks of the Fallschirmjäger at the age of fifty-one. Following the battle of Crete, he was awarded the Knight’s Cross. In the summer of 1942, he oversaw the formation of the Italian elite Folgore Parachute Division. He went on to command the Ramcke Parachute Brigade in North Africa, which distinguished itself in combat against the British, earning him the Oak Leaves to his Knight’s Cross. In February 1943, Ramcke was named the commanding officer of 2nd Parachute Division. The following month he and his paratroopers were sent to the Eastern Front. The 6th Parachute Regiment, which was left in Germany to serve as the cadre for the 3rd Parachute Division in Normandy, was reconstituted under the direct command of the First Parachute Army but remained a formal part of the 2nd Parachute Division. Ramcke led the division in intense fighting against the Russians on the Eastern Front and took command again in expectation of the Allied invasion. Three other officers had commanded the division in the interim; Generalmajor Walter Barenthin, Generalleutnant Gustav Wilke and Oberst Hans Kroh. An extremely tough and demanding commander and adversary, Bernhard Ramcke would squeeze the very best performance from the men of his division.

The 2nd Parachute Division, which had been badly mauled on the Eastern Front, was moved in May 1944 to Köln-Wahn for a period of rest and rebuilding. It comprised the 2nd Parachute Regiment, commanded by Oberst Hans Kroh; 6th Parachute Regiment, commanded by Major Friedrich August Freiherr von der Heydte; and 7th Parachute Regiment, commanded by Oberstleutnant Erich Pietzonka. Each parachute infantry regiment consisted of three battalions each. The division also consisted of the 2nd Personnel Replacement Battalion; 2nd Replacement Training Battalion; 2nd Parachute Artillery Regiment (with three artillery battalions of three batteries each); 2nd Anti-Aircraft Battalion; 2nd Parachute Anti-Tank Battalion; 2nd Parachute Mortar Battalion; 2nd Parachute Machine gun Battalion; 2nd Parachute Engineer Battalion; 2nd Parachute Signals Battalion; and 2nd Parachute Medical Battalion. Of these units, the 6th Parachute Regiment and 2nd Anti-Aircraft Battalion would be detached from the division and assigned to various higher formations during the battle for Normandy. The division would not begin arriving in Brittany until 19 June and would not complete its concentration until the end of the month. During this period, it would remain part of the German Seventh Army reserve in the Quimper–Landerneau area still building its strength. It was far from combat ready, suffering from a number of deficiencies. Although authorised 306 officers and 10,813 NCO and enlisted personnel, it could muster only 161 officers and 6,470 personnel. As for heavy armament, it could only muster four anti-tank guns (of the sixty authorised), twenty-eight mortars (of the 108 authorised), 497 machine guns (of the 739 authorised) and 171 motorcycles, passenger cars, and trucks (of the 1,875 authorised). During the Normandy Campaign, the division, (minus the 6th Parachute Regiment) would find itself defending the port of Brest in western France under the XXV Army Corps and Army Group D.