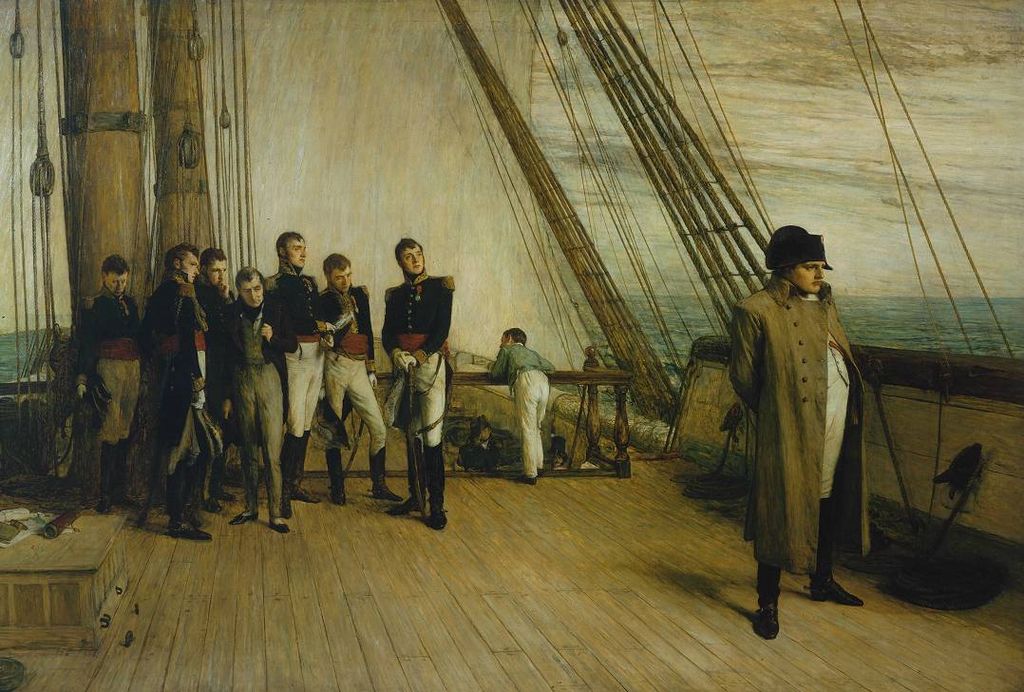

Napoleon Bonaparte on board the British ship Bellerophon by Sir William Quiller Orchardson

Riding in the Basque Roads near Rochefort on the morning of July 15, 1815, the two-decker Bellerophon rocked comfortably in the long swells as a lookout sighted a boat coming out from shore. A familiar-looking figure-running to fat and wearing a cocked hat and a flowing olive overcoat over a green uniform-huddled in the stern sheets. A general’s guard of honor snapped to attention and the boatswain’s whistle wailed a salute as he came through the vessel’s entry port. “At 7 received on board Napoleon Bonaparte, late Emperor of France,” Bellerophon’s log recorded laconically.

Napoleon had regained the empire he had lost in the mountains of Spain and the snows of Russia for a hundred days only to lose it again in the mud at Waterloo. Now, with every escape route closed, he had made arrangements to surrender to the most implacable of his enemies, the Royal Navy, in the person of Frederick Maitland, the “Billy Ruffian’s” captain.

Restive in his exile on Elba, Napoleon had escaped from his Lilliputian domain little more than three months before to find the Napoleonic legend still vibrant in France. Troops sent by the Bourbons to arrest him as he made his way to Paris went over to his standard, and crowds of Frenchmen cheered him everywhere. Facing leveled muskets and bayonets at Grenoble, Napoleon stepped forward and threw open his coat to expose his chest. “Soldiers, if there is one among you who wishes to kill the Emperor he can do so,” he declared. “Here I am!” Following a moment’s hesitation, the muskets were lowered amid cheers and cries of “Vive l’Empereur! Vive l’Empereur!”

The European sovereigns, meeting in Vienna to make the world safe for autocracy, were attending a great ball given by Metternich. As the shocking news buzzed about the ballroom, the dancers abruptly broke off the waltz and stood uncertainly on the floor. Under the menace of the dreaded Bonapart’s return, the monarchs set aside the internal quarrels that had delayed the making of peace to outlaw the Corsican ogre and to pledge themselves to his final destruction. The Continent’s armies were mobilized and the duke of Wellington was appointed to command the advance guard in the Low Countries-the doorway to France-until the immense forces of Austria and Russia could be brought to bear.

Most of Wellington’s Iberian Peninsula veterans were still in America, or on the high seas returning from that country, but every man available was sent in haste to Flanders. For the Royal Navy, the renewal of the war came after many of its ships had been paid off and were being dismantled. Ships that had just been laid up were hurriedly refitted and sent to sea to reimpose the blockade of the French coast. Lord Keith was appointed to command the Channel fleet, and Sir Edward Pellew was sent to the Mediterranean. “I am sending out all I have to look for Boney if he takes to the sea,” Keith told his wife. By mid-June some two dozen men-of-war were on station between Ushant and Finisterre.

Napoleon mustered an army of 128,000 men and marched into Belgium to prevent the Prussians and the British from uniting against him. He was brought to bay at Waterloo on June 18, and fell victim to the steadfastness of the British soldier and the timely arrival on the field of the black-clad Prussians. In one final throw of the dice, Napoleon sent the elite Imperial Guard forward to attack Wellington’s position on a plateau overlooking the battlefield. Undeterred by the pounding of enemy artillery, the guardsmen pressed forward like a rising tide. It crested the ridge, and for a moment the British line disappeared. And then, in a wild hail of bullets, the wave faltered and receded. By nightfall, Napoleon’s last campaign was over, and 50,000 men-French, British and Prussian-had been killed or wounded.

For the third time, the Emperor abandoned an army in the field and hastened back to Paris. But there was no support for him there, and the empire slipped through his fingers. He toyed with the idea of trying to run the British blockade in a French frigate or a neutral American vessel and sailing to the United States, where anti-British sentiment was strong. No decision was made and in the confusion, Napoleon left Paris for Rochefort, riding past his unfinished Arch of Triumph with a few faithful followers. On the way he stopped at Malmaison, where he had lived with Josephine before their divorce. Briefly, he lingered alone in the room where she had died the previous year. Then he said his farewells to his mother and other relatives, including his two illegitimate sons.

From a window of the grim, gray house on the Gironde where he took shelter, the Emperor could see Bellerophon standing offshore like a sentinel blocking his escape. No ship better epitomized the British sea power that had always stood in the way of his conquests. The old ship had fought at the Glorious First of June, the very first fleet action of the war against France in 1794; at the Nile, where his dreams of oriental glory were dashed; and finally at Trafalgar, where his fleet had been annihilated. One morning, he heard Bellerophon firing her guns to celebrate the allied capture of Paris and the return of the Bourbons.

Always a master of the unexpected, Napoleon had one final surprise. Realizing at last that escape was impossible, he decided to throw himself on the mercy of the British. Writing directly to the prince regent, he asked permission to retire to the English countryside outside London and made arrangements to surrender to Captain Maitland. Like all other British naval officers who might capture Napoleon, Maitland had instructions to immediately return with the prisoner to the nearest English port. While the problem of what to do about him was debated, Napoleon remained on board Bellerophon, which went first to Tor Bay and then to Plymouth, where she remained offshore.

As close as Napoleon Bonaparte ever got to the United Kingdom- as ‘guest’ aboard HMS Bellerophon (74). Beautiful oil painting by John James Chalon: Scene in Plymouth Sound in August 1815

As she lay in the sound there, the ship became a tourist attraction. Hundred of small boats surrounded her, and Napoleon enjoyed the attention of his foes. Each day, no matter what his anxiety about his fate, he appeared on deck in plain view of the tourists, wearing the uniform of a colonel of the Imperial Guard. Sometimes he smiled and raised his hat to the ladies. He also expressed a keen interest in the operation of Bellerophon, questioning her officers and men about their duties. Language was no barrier; a number of the ship’s complement spoke some French or Italian, his two languages. A midshipman would recall with delight many years later that when he gaped at the emperor, “the great Napoleon” smiled at him, cuffed his head lightly, and pinched his ear.

On July 31, Napoleon learned his fate. Much to his anger, he was told that he was to be banished to the remote South Atlantic island of St. Helena, from which it was thought he would be unable to escape and again upset the balance of Europe.* With a handful of oddly assorted followers, he sailed a week later in Northumberland, seventy-four, for his place of exile. Once at St. Helena, he entered into a strange half world between freedom and prison. There he spent the remaining six years of his life, gazing out to sea, rewriting history, and placing on others the blame for all that had gone wrong.

The navy that had played such a vital role in bringing about Napoleon’s downfall did not long survive his reign. As soon as peace was assured, the ships were paid off, and the crews were mustered out. One by one, the twenty-seven ships of the line that had fought at Trafalgar met their fates: Agamemnon, “Nelson’s favorite,” had already broken her back in the River Plate; Defence was wrecked off Jutland and Minotaur at the mouth of the Texel; Defiance was degraded to a prison ship, and the same fate befell Leviathan as well as Bellerophon after her moment in the limelight; Ajax caught fire and blew up at Tenedos; Collingwood’s Royal Sovereign was not even allowed to keep her name but finished her career as Captain, the receiving ship at Plymouth; Téméraire-“The Fighting Téméraire”-went to the shipbreakers, but not before being immortalized by J. W. Turner in a famous painting. Wreck, fire, convict hulk, target ship, the breaker’s yard complete the roll. With the exception of Victory. Nelson’s Victory. all vanished, leaving only a glorious memory.

In the end, Napoleon Bonaparte best summed it all up. While on board Bellerophon, the Emperor discussed with Captain Maitland the defense of Acre, in which the captain had taken part. Napoleon concluded by saying:

If it had not been for you English, I should have been emperor of the East;

but wherever there is water to float a ship, we are to find you in our way!