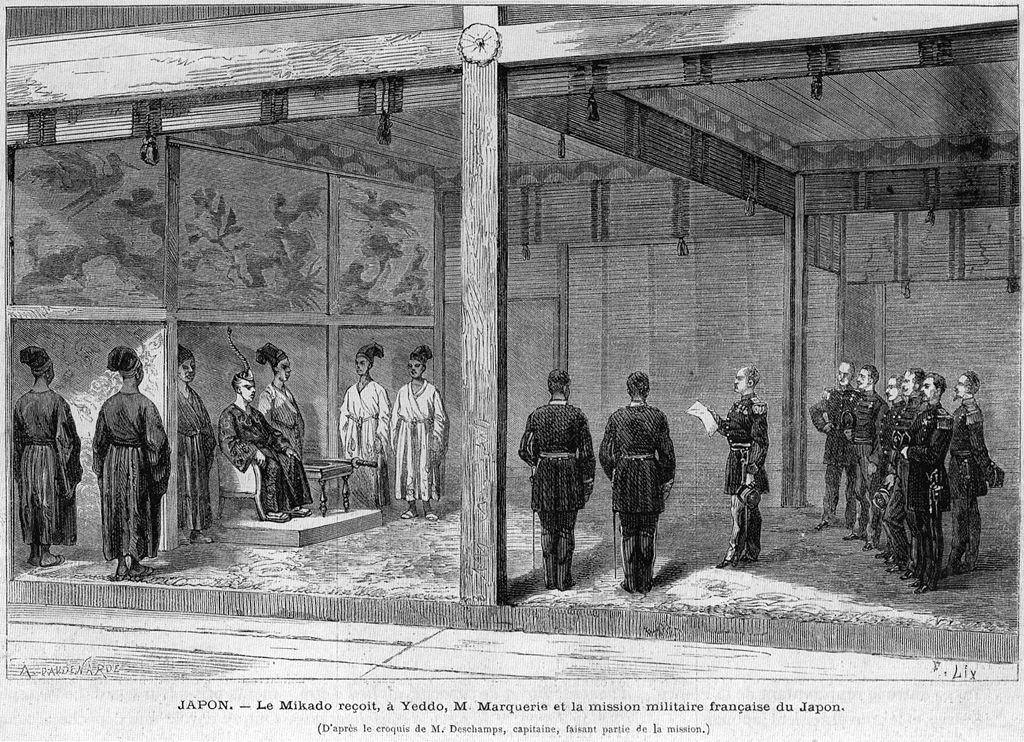

Reception by the Meiji Emperor of the second French Military Mission to Japan, 1872

The Conversion to Divisions

In January 1880 Yamagata had warned the emperor of the dangers posed by Russia’s remorseless advance into East Asia and China’s military modernization. Japan’s lengthy coastlines left it especially vulnerable to attack from multiple directions or to a naval blockade and isolation. Yamagata would neutralize such threats by fortifying small off-shore islands as the nation’s first line of defense and completing the coastal battery construction projects around Tokyo Bay that the government had suspended to pay for the Satsuma Rebellion. He voiced a recurrent theme: without a strong military, Japan could not maintain its sovereignty from the European powers—who, he claimed, built armies and navies regardless of national wealth or poverty.

The army’s January 1882 budget proposed a ten-year plan to field seven modern infantry divisions with supporting troops, improve coastal defenses, and upgrade weaponry, especially artillery. It reflected Yamagata’s concern over the growing tension with Korea and China, which appeared to justify a larger army. Since 1877 the army had expanded slowly from around 40,000 officers and men to more than 46,000 by 1882, and its budget grew accordingly, from about 6.6 million yen (US$6 million) to 9.4 million yen (US$8.5 million), respectively. Army expansionism to counter perceived continental threats was consistent with the 1870 calls for a Korean expedition and overseas expansion. Yet it also demonstrated the government’s concern that Korea under foreign (non-Japanese) influence would pose an unacceptable threat to Japan’s home islands and that a larger military was necessary for self-defense against invasion.

Outbursts of anti-Japanese violence in Korea during the summer of 1882 culminated that July with the murder of the Japanese military adviser to the newly organized Korean army and an attack against the Japanese legation in Seoul. Tokyo sent two infantry companies to restore order, made demands on the Korean court, and moved large forces to Kyūshū opposite Korea during the so-called Jingo Incident. The Korean court promptly sought assistance from China, which dispatched 5,000 troops that eliminated pro-Japanese elements in the rebellious Korean army, installed a pro-Chinese Korean faction in power, and reasserted Chinese influence throughout the peninsula.

Although the general staff had an 1880 operational plan for offensive operations in north China, it was premised on wishful thinking because Japan was too weak militarily to confront the Chinese empire. During the Korea crisis the army remained passive, fearful that China might seize Tsushima Island to use as a springboard to attack Kyūshū. If that occurred, the navy would support the Tsushima garrison by cutting the sea-lanes from China or Korea, and the army would defend strategic locations on the Kyūshū coast.

The Chinese intervention unmasked the government’s and the army’s inability to protect Japanese interests in Korea. In August 1882 Yamagata reiterated to the throne the need for military expansion to counterbalance China’s military modernization program and conduct in Korea. In his view this necessitated expanding the navy to forty-eight warships and restructuring the army into seven divisions plus a 200,000-man reserve by 1885. Lt. Gen. Miura Gorō along with Lt. Gen. Soga Sukenori, both of whom had previously petitioned the emperor on the Hokkaidō sale issue, opposed a larger standing army. Much like Yamada Akiyoshi in the 1870s, they advocated a small standing army, perhaps 30,000 men, organized as a one-division force backed by a home guard available for duty during emergencies. Their proposal would also reduce the current three-year active duty obligation for conscripts to a single year.

The general staff’s western bureau director, Col. Katsura Tarō, however, insisted on a streamlined modern division structure because combining garrisons during wartime created patchwork and unwieldy units with huge administrative and personnel overhead that were too large to move rapidly. Yamagata supported Katsura and expected the finance ministry to impose new taxes on tobacco to pay for the enlarged military and division conversion expenses. But Finance Minister Matsukata Masayoshi cited the perilous state of Japan’s finances that made additional military spending impossible. In September, Minister of the Right Iwakura Tomomi advocated an emergency tax to underwrite military expansion and modernization. Emperor Meiji endorsed Iwakura’s recommendation and in November notified prefectural governors that military expansion was a matter of vital national security. The next month the government enacted emergency tax legislation to pay the increased personnel costs associated with the conversion to a seven-division force structure and the improvement of coastal fortifications.

About half of the additional annual tax revenue went to the army (1.2 million yen), with the remainder divided between naval shipbuilding and coastal defense construction programs spread over eight years. The National Defense Council (kokubō kaigi), established in March 1883, coordinated coastal defensive responsibilities between the army and the navy, establishing Japan’s first line of defense on the high seas, its second along the coast, and its third, and final, on homeland soil.

Advocates of a larger standing army, including Yamagata, Ōyama, Katsura, and the commander of the 2d Guard Infantry Brigade, Maj. Gen. Kawakami Sōroku, next rewrote conscription legislation to create a much larger reserve force. Reforms in 1883 created a first reserve with a four-year obligation and second reserve with five additional years of military commitment. The new legislation also eliminated paid substitutes, tightened restrictions on exemptions, and provided for volunteer one-year enlistments.

Although army budgets increased substantially in 1883 and 1884 and personnel grew from 42,300 in 1880 to 54,000 by 1885, division conversion lagged behind schedule because the purchase of new weapons and equipment, the coastal defense projects, and naval expansion created trade imbalances and unacceptable government deficits. These were especially sensitive issues because Foreign Minister Inoue Kaoru, hoping to impress the western powers with Japan’s fiscal responsibility during renewed negotiations to secure treaty revision, rejected running a deficit to pay for military modernization. At the same time, however, Inoue and imperial councilor Itō Hirobumi recognized the need for a stronger military to offset the rise of Chinese and western influence in northeast Asia. French and British naval squadrons were active around Taiwan and Korea, respectively, the Russian Vladivostok Squadron routinely operated in Korean waters, and China was modernizing its Northern Fleet to control the Yellow Sea.

Inoue would economize by cutting the army by 20,000 men, reducing terms of conscription by six months, and establishing a joint general staff. The savings would pay for limited naval expansion. Japan would rely on alliances either with England or Russia to ensure national security at a cheaper cost. Inoue drew support from big-army opponents like Miura, army Vice Chief of Staff Soga Sukenori, Minister of the Left Prince Arisugawa, and the retired but influential generals Tani and Torio. Yamagata, War Minister Ōyama, and Katsura adamantly opposed the initiative. According to Katsura, the hallmark of a first-class nation was an army capable of operating beyond its national borders, and Japan’s inability to project military power overseas would relegate it to the status of a perpetual second-class power.

Looking to save money, Emperor Meiji agreed with Arisugawa, Miura, and Soga, who also had the support of Prime Minister Itō. But Ōyama insisted that the volatile international situation placed Japan in such grave danger that the larger force structure was essential. When his obstinate opposition threatened to rupture Satsuma-Chōshū political hegemony, Inoue gave in to Ōyama’s demands.

The military share of the budget increased substantially, from about 15 million yen in 1885 to more than 20.5 million yen the next year, with the army getting an additional 2.2 million yen and the navy 3.5 million. The resulting huge deficit ruined Inoue’s fiscal plans, and when serious negotiations on treaty rectification began in 1886, western insistence on certain prerogatives produced a political and popular backlash that made amendment impossible. Tani resigned his portfolio to protest the terms of the proposed treaty revision, and Miura’s and Soga’s unwavering opposition to the government’s concessions on the emotional issue of treaty revision cost them Inoue’s and Itō’s backing. Their fall was attributable to their loss of patronage and support from the prime minister and the foreign minister over the intertwined issues of army expansion, treaty revision, and fiscal retrenchment. The break-up of the opposition coalition of conservative generals, the court, and civilian ministers left Yamagata and Ōyama free to implement their plans. Between 1875 and 1882 the ordinary military budget ranged from about 14 to 19 percent of the national budget. Thereafter naval construction and army modernization (the conversion to divisions) steadily increased it to a 31 percent share in 1892.

Construction started in late 1886 to improve Tsushima’s coastal defense fortress, and the next year the emperor’s personal donation of 300,000 yen to the army engineer branch launched a nationwide campaign that solicited 2.3 million more yen from wealthy individuals to employ additional laborers for work on an expanded network of fortifications. The same year the army assigned division numbers to the respective garrisons; for example, the Tokyo garrison became the 1st Division. The army then projected that the conversion process would take two years, but recurrent funding shortages ultimately delayed the Guard conversion. Nevertheless, in May 1887 the army officially abolished the garrisons and adopted the division force structure. Picked officers who would lead and staff the new divisions were sent to Europe for extended study of military organization and force structure. By the time conversion was completed in 1891 the army fielded seven modern divisions and had a reserve mobilization capability of 240,000 troops.

The army modeled its original 1888 division force structure on the Prussian mountain division, but with a larger peacetime establishment of about 9,000 officers and men that would double in wartime with the addition of an infantry brigade, a cavalry squadron, and various support units. The 1893-type division was organized around two infantry brigades each with two infantry regiments (a so-called square division) and had 18,500 officers and men at wartime strength as the gradual expansion of the active ranks, reform of conscription system, and volunteers provided cadre and reserves for rapid wartime expansion. The modern mobile division complemented the fixed coastal fortresses already under construction by enabling troops to move rapidly and reinforce threatened points or contain enemy landings.

The phased transition to a division structure is often regarded as prima facie evidence that Japan harbored offensive continental aspirations and tailored its army for overseas deployment and aggression. No doubt some high-ranking officers dreamed of imperial expansion on the Asian continent, but not until 1900 did the general staff begin formal planning for offensive operations there. In the meantime, the army continued to emphasize coastal defense against a Russian attack, and as late as 1891 the theme of the annual grand maneuvers was repelling an amphibious invasion.

It would likewise be inaccurate to say military preparations were not aimed at an external threat, but an operational offensive capability was part of a larger policy of strategic defense designed to spare Japan from foreign invasion. Rather than an indication of imminent aggressive warfare, the division force structure was a long-considered adaptation of the most up-to-date western military organization at a time when Japan was striving to master the secrets of the West’s success. Rectification of the unequal treaties, rebuilding the financial and political system, and checking the Russian threat from the north were the priorities of the Meiji government. In that context, the division organization was simultaneously offensive, because of the possibility of intervention in Korea due to deteriorating relations with China, and defensive, because of the emerging Russian threat in northeast Asia.

Educational Reforms and the Influence of Maj. Jakob Meckel

The growing number of critics of oligarchic rule during the mid-1880s, the violence of the people’s rights movement, and the specter of antigovernment political parties in control of the promised Diet fed Yamagata’s determination to isolate the army from those who would control it for political ends different from his own. One means to this end was to reorganize the army’s administrative system.

Army doctrine, training, and education were haphazard well into the 1880s, relying on at least five different versions of translated French infantry manuals between 1871 and 1885. Military organization followed the French model: training a peacetime establishment in drill and ceremonies, military courtesy, and proper care of the uniform and equipment. Tactics stressed junior officer and NCO responsibilities as small-unit leaders (battalion echelon and below) but were learned by rote and consequently lacked practical application and originality. French instructors at the military academy, for example, taught cadets to prepare detailed tactical orders and rigidly apply approved formations (columns shifting to skirmisher lines) to small-unit (battalion and below) tactical problems. Senior Japanese officers believed that the overemphasis on minor tactics and technical expertise had hampered strategic planning for large-unit operations during the Satsuma Rebellion. Their hard-won experience in that conflict seemingly made foreign instruction irrelevant, and in 1879 the government terminated the French military mission’s contract. But startling European advances in military science and weaponry could not long be ignored. Many officers admired the emerging Prussian doctrine, proven against the French in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, and thought it more suited for higher-echelon operations involving brigades and divisions.

In 1884 a delegation composed of four senior officers—Army Minister Lt. Gen. Ōyama; Lt. Gen. Miura, now commandant of the military academy; Col. Kawakami Sōroku, commander of the 1st Guards Infantry Regiment; and Col. Katsura conducted a year-long inspection tour of European armies. With the exception of Miura, who had been trained by the French, the delegation favored the Prussian military system, which was widely regarded as the standard for modern armies. Miura’s views were well known, and he had likely been included to balance regional sensibilities; Ōyama and Kawakami were from Satsuma, and Katsura and Miura hailed from Chōshū. In any case, Ōyama overrode Miura’s objections and asked Prussian War Minister Paul von Schellendorff to recommend a senior instructor for Japan’s staff college. Von Schellendorff nominated Maj. Colmar von de Goltz, but the Chief of Staff, Helmut von Moltke, wanted Goltz to rebuild the Turkish army, which had been recently defeated by Russia. Moltke then nominated 43-year-old Maj. Klemens Wilhelm Jakob Meckel, a tactician, not an instructor, for the assignment. The delegation returned to Japan in January 1885, and Meckel arrived in Tokyo two months later.

Tall, ramrod straight, and imposing, the bald-headed Meckel looked like the stereotypical Prussian officer martinet. Indeed, he was an exacting taskmaster and demanded the same attention to duty and detail from students. But he lacked arrogance, enjoyed drinking, and was a genial personality.

Unlike the large French advisory mission, which had numbered as many as forty officers in the mid-1870s, Meckel’s advisory group never numbered more than seven. The army also retained four or five French advisers into the early twentieth century as language instructors and ordnance experts. Several Italian military advisers served in Japan between 1884 and 1896, a period when the army relied on Italian-produced bronze artillery guns.

Meckel and his team introduced the Prussian military education model, which switched the emphasis from technical proficiency to a more general military education, especially in the staff college, whose course was extended to three years. Meckel’s dominance at the staff college changed the way Japanese officers thought about warfare, and his intellectual synthesis of modern strategy and traditional martial values held widespread appeal among the officer class. Meckel, for instance, preached that victory or defeat in battle was not simply a function of advanced weaponry. The decisive feature was élan, and he stressed the importance of the psychological dimension of warfare and offensive spirit, a philosophy of warfare that meshed nicely with the army’s existing concepts of seishin, or fighting spirit. With the exception of foreign languages, Meckel refocused the new curriculum almost exclusively on military art and science—tactics, military history, ordnance, gunnery, fortification, communications, terrain studies, equestrian arts, and health and sanitation matters. His slighting of logistics in favor of instruction devoted to techniques of operational planning and command found a receptive audience, but it left students with a poor grasp of the planning and organization of the movement of troops, equipment, and supplies and little knowledge of the science of modern military logistics.

Meckel used primary source documents and staff rides to educate officers in the application of theory on tactics and the influence of terrain on maneuver and battle, basing instruction on military history, not military theory. Lessons placed a premium on resolute decision making and glossed over intelligence gathering because that could delay action. Language was a problem because the question-translation-answer-translation format of Meckel’s classroom lectures made them lengthy and boring. Written translations of the lectures were, however, widely distributed to officers throughout the army as study materials.

Under Meckel’s guidance the army switched to the German field manual that emphasized importance of the company echelon in tactical formations. Standardized training and procedures accompanied the shift to the new manual. Until 1887 individual regiments had determined their training tables, but that year troop training regulations standardized training army-wide. In keeping with the Prussian reforms, the army adopted the so-called family training concept, which placed the company commander in charge of conscripts’ training. The army expected junior officers to both lead and teach and demanded proficiency in military art as well as the ability as instructors to inculcate the ideal of fighting spirit into the ranks. By 1889 the Prussian draft 1884 field service regulations had been translated into Japanese, and two years later the army completed the transition from the French to the Prussian training regimen and immersed recruits in training and drilling according to the new infantry manual.

Rightly praised as the father of modern military education in Japan, Meckel exerted a significant and enduring influence on the army. Yet his departure from Japan was clouded, apparently because certain influential Japanese officers suspected Meckel was a German spy. He received gifts and accolades but had to insist to get the emperor’s personal seal on his commendation and was awarded a lesser-grade medal. Nonetheless, Meckel took lasting pride in his accomplishments and his Japanese students.

As the military education system became institutionalized, officers took competitive entrance examinations for admittance to the staff college (in 1886 the course was extended to three years). At a minimum, candidates had to be first lieutenants, be in good health, possess a good service record, and demonstrate intellectual ability. Other qualifications mandated a minimum of two years service with a troop unit, an age limit of 28 (specialists like artillerymen and engineers were eligible until age 30 because of the extra technical schooling required in those branches), and the recommendation of the candidate’s commanding officer. Transportation branch officers initially were ineligible for admission because there was no logistics branch on the general staff, another indication of the army’s low regard for the services of supply.

Normally it took a junior officer two or three years to prepare himself for the staff college examination. Because a candidate’s admission to the staff college reflected favorably on his regiment, over time it became customary for battalion or regimental commanders to assign their most promising junior officers to light duties to enable them to study and prepare for the exam. At first, class ranking was critical, and beginning in 1887 the commandant or his deputy reported student grades to the chief of staff, who used the results to determine subsequent assignments and promotions. After the turn of the century, class ranking declined in importance as a factor in promotion, at least to the general officer ranks, and battlefield valor and practical experience with troop units were given greater consideration.

The army also schooled promising officers at foreign military institutions. In 1882 there were nine student-officers in France and three in Germany; in 1898 there were three in France and twelve in Germany. Throughout its existence the army routinely assigned officers to foreign military schools, almost all in Europe, and like their navy counterparts, a high proportion of senior army officers had overseas assignments as students, attaches, or observers on their service records. Popular wisdom credits the imperial navy with producing cosmopolitan and sophisticated officers while dismissing army officers as provincial bumpkins ignorant of the West. But the army routinely dispatched its best and brightest to Europe for study and professional grooming.

Branch schools were established to educate officers and train troops in their respective military specialties. The army ministry created the transport corps bureau in 1885 and issued the transport corps field manual the next year. The army managed its own medical training school in 1871 but because of the length of medical training and the expertise demanded of instructors in 1877 abolished it and used the Tokyo University Medical School to train military doctors. After graduation they received specialized instruction in military medicine. In 1888 the army reestablished its medical school as a postgraduate center for army doctors, to offer the latest surgical techniques to reserve doctors and to train medical orderlies. In 1894 it became the army sanitary school.

Prussian influence likewise changed the military academy. After 1890 cadets no longer received commissions upon graduation. Instead, using the Prussian model, before entering the academy they spent one year serving in a unit (six months if preparatory school graduates) as cadets, nineteen months at the academy, and six months after graduation as cadet aspirants with a unit. If the aspirant successfully completed his duty assignment, he received a commission as a second lieutenant. Later reforms in 1920 added a two-year preparatory course at the academy followed by six months attached to a unit as a cadet, then twenty-two months at the academy’s main course, followed by two months with a unit as an aspirant.

In 1896 the army adopted the Prussian system of separating the central military preparatory academy from regional preparatory academies. Thirteen-year-old boys entered the three-year course to prepare themselves for a two-year course at the central preparatory academy in Tokyo. Except for the sons of deceased soldiers or senior bureaucrats, the preparatory schools charged tuition, making it difficult for the poor to send their sons into officers’ careers. After graduation, cadets spent six months with a unit before entering the military academy. Maj. Gen. Kodama Gentarō insisted on emphasizing spiritual education in the cadet academies, where it became a standard feature of the curriculum from the 1890s.