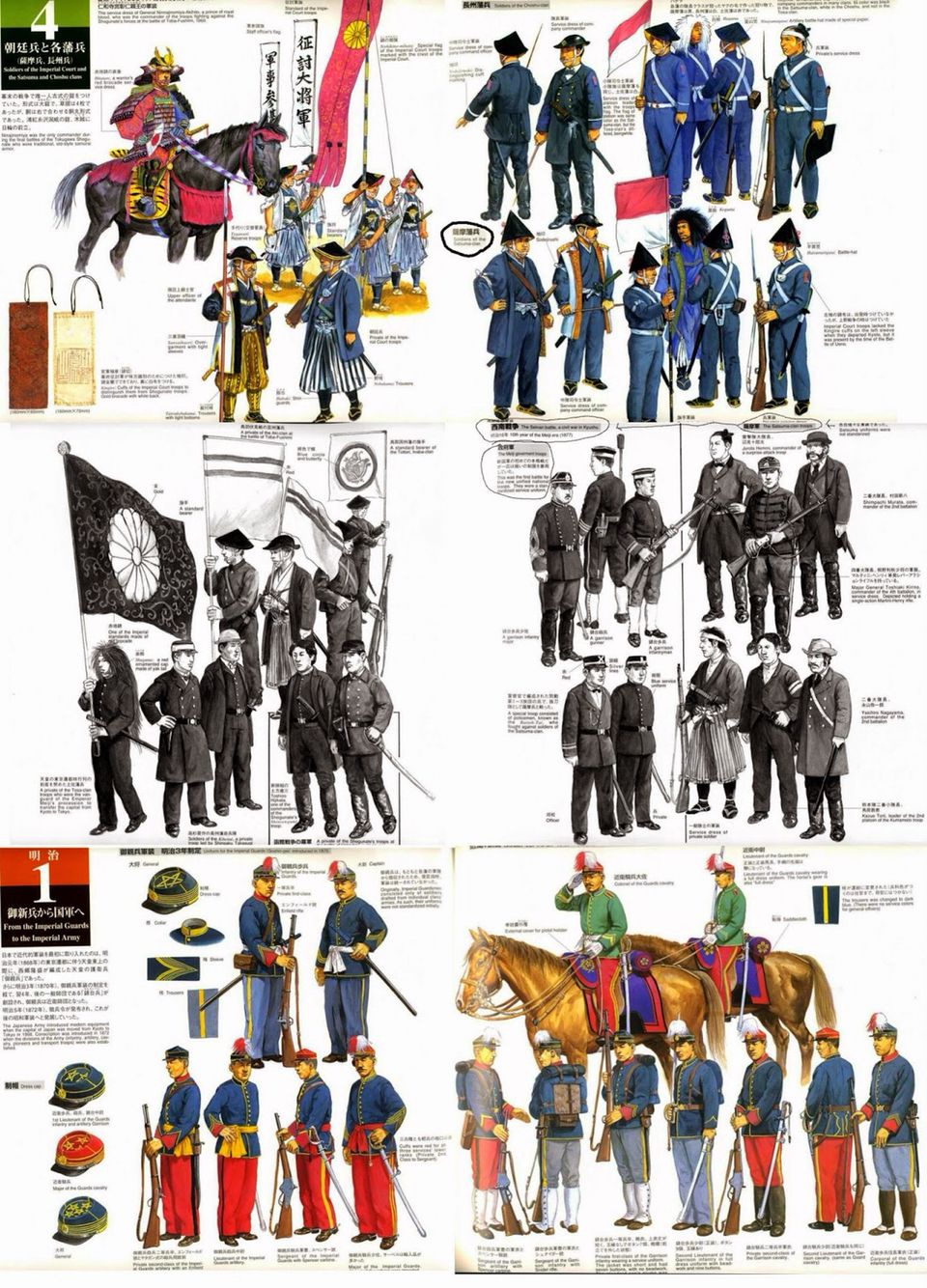

Uniforms during the Boshin War and Meiji era

On May 14, 1878, the most powerful man in Japan, Minister of Home Affairs Ōkubo, was riding alone in his unescorted carriage from his Tokyo residence to a morning appointment. Six sword-wielding former samurai surrounded his carriage in a narrow lane and hacked and stabbed him to death. The ringleader later admitted that the killers feared an Ōkubo dictatorship and had planned to murder him since they heard of Saigō’s suicide. One captured assassin joked to interrogators that if life was a stage, their act might be seen as a cheap burlesque.

Besides Ōkubo’s brazen murder, lingering questions of loyalty and obedience to orders clouded the national army’s victory over Saigō’s warriors. In the aftermath of the rebellion, many units felt slighted by a government that neither recognized nor rewarded their wartime sacrifices. For example, the Imperial Guard artillery battery, despite its prominent wartime role, received belated commendations and smaller monetary awards than soldiers had expected. The parsimoniousness reflected the government’s financial retrenchment policy deemed necessary to repay the enormous cost of the war, including more than 30 million yen in supplemental funding (five times the army’s annual budget). In order to balance the national budget, in December 1877 the council of state ordered 20 percent across-the-board reductions to ministry budgets. The following May the army ministry reduced military pay by 5 percent and temporarily suspended work on its showcase coastal fortification construction projects. These actions only added to the list of soldiers’ grievances.

On the night of August 23, 1878, about 200 noncommissioned officers and enlisted men of the Guard artillery battalion garrisoned near Tokyo’s Takebashi Bridge mutinied, murdered their commanding officer and the officer of the day, perfunctorily shelled the finance minister’s official residence, and demanded to speak directly to the emperor. The army ministry, having been tipped off in advance, quickly crushed the insurrection. Courts-martial held in October sentenced 55 mutineers to death and punished over 300 more (including accomplices in other units) with prison terms or banishment. Unrewarded wartime service had sparked the so-called Takebashi Incident, but the trials also revealed that many of the enlisted troops were active in the nascent liberty and people’s rights movement, a popular national political campaign demanding democratic rights from the Meiji government that leaders like Yamagata regarded as subversive and dangerous.

Yamagata sought to inoculate the army from the virus of mutiny by appealing to a romanticized imperial past. Fifty days after the Takebashi Incident, the army distributed his Admonition to Soldiers (gunjin kunkai) to all its company commanders. The instructions, aimed specifically at the officer corps, stressed that strict military discipline and unquestioning obedience to a superior’s orders were the foundation of the military institution. He portrayed officers as the heirs to a glorious samurai tradition in which loyalty and valor were the “way of the warrior” (bushidō).3 Real samurai were discredited, so officers and conscripts were indoctrinated to aspire to the greatly romanticized version of idealized warriors.

Yamagata also warned that disobedience to orders led to military involvement in political activities and spread subversion among the ranks. He justified that claim with another dubious assertion: that in ancient times the army had belonged to the emperor and was therefore above politics. By equating obedience to a superior’s orders with compliance to a direct imperial order, Yamagata further implied that a superior’s orders had to be followed unquestionably, regardless of legality. In sum, Yamagata wanted an apolitical army under his control to prevent a reoccurrence of the Satsuma Rebellion or Takebashi Incident, and one means to achieve this goal was to make the military directly responsible to the emperor, thereby insuring imperial control of the army.

Institutional Reforms

In the decade following the Satsuma Rebellion, the army thoroughly reorganized. The process was gradual, but the reforms were radical. The army’s fundamental institutions—a general staff, an inspector general, a general staff college, and a division force structure—evolved, but only after acrimonious debates within the army that pitted Francophile traditionalists against pro-Prussian reformers.

In the wake of rebellion, mutiny, and popular demonstrations, Yamagata feared that antigovernment politicians would restrict the army’s freedom of action, or that antigovernment forces might incite the ranks to revolt and overthrow the government. These concerns justified reforms to ensure an apolitical army by removing the supreme command from the political arena. The ruling oligarchy concurred because they wanted no more Saigō Takamoris—men who held dual military-civilian appointments and might use their military power to usurp the civilian government. One possible solution was to create a general staff with direct access to the emperor that could execute imperial commands unencumbered by the agenda of civilian political leaders or military administrators.

The idea was an extension of Yamagata’s 1874 establishment of the sixth bureau, augmented with fresh ideas from Europe. Capt. Katsura Tarō, one of Yamagata’s many Chōshū protégés, had spent the Satsuma insurrection studying at the Prussian military academy at his own expense. He returned home in 1878 convinced of the merits of a general staff that was independent of the army ministry’s administrative control and enjoyed direct access to the emperor. That October, apparently on Katsura’s advice, Yamagata formally recommended to the council of state the separation of staff and administrative functions.

The council of state abolished the general staff bureau on December 5, 1878, and established a general staff separate from the army minister and directly responsible to the emperor, although without clearly delineating the new staff’s authority. During peacetime the general staff controlled the Imperial Guard and regional garrisons, and the chief of staff, an imperial appointee, also served as the emperor’s highest military adviser. During wartime the chief of staff assisted the emperor with military matters but lacked command and decision-making authority, those formally being the prerogatives of the emperor. He could, however, issue operational orders in the emperor’s name. This provision institutionalized the prerogative of the independence of command (tōsuiken) executed in the emperor’s name as supreme commander (daigensui).

The new general staff had two bureaus divided by geographic interest. The eastern bureau was responsible for the garrisons in the Tokyo and Sendai military administrative districts as well as Hokkaidō, Siberia, and Manchuria; the western oversaw the other four regional garrisons plus Korea and China. Each bureau had operational and intelligence functions, and two smaller subsections handled administration, prepared gazetteers, translated materials, and archived documents.

Within days of creating a general staff, Yamagata, who became the first chief of staff, established a superintendency on December 30 as a separate headquarters in Tokyo. It too reported directly to the emperor, coordinated army-wide training, standardized tactics and equipment, ensured that units carried out the general staff’s orders, and enforced army regulations. The superintendency had no director, and the duties of its headquarters in Tokyo were limited, but its three regional superintendents enjoyed broad authority because they reported directly to the emperor, bypassing the general staff and army ministry. In peacetime each regional superintendent was responsible for the education and training at two garrisons and in wartime commanded a two-division corps formed by combining the garrisons’ forces.

The three regional superintendents were superimposed on the existing garrison system, and each was of lieutenant-general rank; Tani supervised the eastern commandaries, Nozu the central, and Miura the western. Each had the authority to enforce orders issued by the general staff with imperial approval. This reorganization of the army’s administrative system with a new inspectorate and an independent general staff was an attempt by Yamagata and Army Minister Ōyama to consolidate their power and, by extension, the Satsuma-Chōshū monopoly on senior army positions.

The Satsuma Rebellion had exposed the need for trained staff officers to plan and coordinate operations, formulate strategy, and remedy deficiencies in operational planning. In 1882 the army had a total of forty-nine staff officers: fourteen assigned to the general staff, five to the army ministry, and the remaining thirty to the various garrisons, the Imperial Guard, or the military districts. That year the army opened the general staff college to train and educate officers for future staff assignments. Nineteen students were selected for the three-year course. The first year was remedial and concentrated on the study of foreign languages (German and French), mathematics, and drafting for engineering and map-making purposes. Officer-students studied military organization, mobilization, tactics, and road march formations in their second year; their third year focused on the mechanics of overnight unit bivouacs, reconnaissance, strategy, and military history. Instruction in tactics and strategy was initially limited because of a lack of qualified Japanese instructors and the continuing debate within the army over adopting French or German doctrine. From its inception, the staff college had a close association with the throne, personified by the emperor’s personal presentation of an imperial gift to the top graduates: a telescope in the case of the first six graduating classes, and thereafter a sword.

Another manifestation of the link between emperor and army was the conversion of Ōmura’s Shōkonsha concept of a public memorial to commemorate those who died in the Boshin Civil War to a state-sponsored Shintō shrine to promote imperial divinity and Japanese uniqueness. In June 1879 the Shōkonsha was renamed the Yasukuni Shrine, with a status second in ranking only to the imperial shrines. The home ministry, army, and navy administered the shrine while the army paid for its upkeep. For purposes of army morale, the army reinterred its war dead from the Satsuma Rebellion at the Yasukuni and announced that they had been transmogrified into spirits guarding the nation. Interment was strictly limited to those killed in action; soldiers who died on active service during peacetime were interred in army-designated regional cemeteries.

Promulgating a New Ideology

Political agitation since the mid-1870s for a constitution and a parliament gradually matured into a campaign for freedom and people’s rights, a broader-based political movement whose origins lay in samurai discontent. By the late 1870s, peasant unrest had also increased because the government resorted to deflationary fiscal policies to repay the foreign loans that underwrote the military costs of suppressing Saigō’s rebellion. Retrenchment caused a sharper decline in market prices for rice and raw silk, the cash crops of the peasantry, than in overall consumer prices. Many peasants fell into debt, borrowed money to buy seed or pay land taxes, and in some cases were unable to repay the loans. Disaffected peasants organized into groups seeking debt relief, and outbreaks of armed violence—some led by local political party branch members—erupted in central Japan during 1882.

Soldiers had also been active in the people’s rights movement since its inception. In January 1879 police arrested several enlisted men assigned to the Guard infantry regiment for conspiring to murder their company commander and high-ranking government officials. Sometime later they apprehended a disgruntled artillery officer who was threatening to bombard the imperial palace. Dissatisfied over the awarding of medals, troops also complained about the five-year term of active service for those assigned to the Guard, demanded special pay and allowances, and sought political redress for grievances over the living conditions of enlisted men in garrisons.

Yamagata did initiate reforms that shortened the Guards’ length of service and reduced pay inequalities. Conscription reforms in October 1879 extended terms of reserve duty from four to seven years by creating a first (three-year) and second reserve (four-year), halved the fee to purchase a substitute, and tightened deferments. Yamagata refused, however, to allow soldiers greater political expression, believing that it would undermine military discipline. As if to underscore his fears, in 1880 a soldier stationed in Tokyo committed suicide in front of the imperial palace when the government refused to accept his petition calling for the opening of a parliament.

Internal army dissent also targeted the government and Yamagata, particularly the council of state’s fire sale of the Hokkaidō Colonization Office’s assets to private Mitsubishi interests allegedly to defray the retrenchment costs. Among the most vocal and persistent critics were four general officers: lieutenant generals Torio Koyata, Guard commander; Tani Tateki, commandant of the military academy and the Toyama Infantry School; Miura Gorō, superintendent of the western commandary district; and Maj. Gen. Soga Sukenori, acting superintendent of the central commandary district. The four claimed to be acting from bushidō principles when in September 1881 they petitioned the throne to reverse the transaction.

The people’s rights movement also criticized the sale, and the generals’ petition forged another link in the chain of protests during the so-called crisis of 1881, which climaxed that October when the emperor canceled the sale and promised a national assembly by 1890. To prepare for the assembly, a cabinet system of government would replace the council of state in 1886 (the change actually occurred in December 1885).

Liberal members of the government resigned to join the popular rights movement in anticipation of greater political opportunity. The four generals remained on the active duty list, continued to hold important positions, and formed the conservative opposition to Yamagata’s efforts to reorganize and unify the national army. The involvement of enlisted troops and senior officers in political activity stimulated army chief of staff Yamagata’s fears about the military’s security and reliability.

On January 4, 1882, Yamagata promulgated the imperial rescript to soldiers and sailors to remedy what he perceived as lax military discipline and military involvement in the popular rights movement. Its audience was the army rank and file, and the language was clearer and easier to understand than the highly stylized 1878 injunctions to officers. The message, however, was the same. Yamagata reemphasized respect for superiors, the spirit of courage and sacrifice, and absolute obedience because superiors’ orders were direct commands from the throne. Soldiers and sailors, he wrote, should loyally serve the emperor, their commander-in-chief, “neither being led astray by current opinions or meddling in political affairs,” and always recalling that “duty is heavier than a mountain while death is lighter than a feather.” Yamagata again relied on hoary martial values to send a message of modernity based on loyalty to the emperor and nation, not one’s former domain, and issue a caution against political involvement. The 1882 memorial would shape official popular ideology and the notion of duty and loyalty to the emperor.

The army’s role in controlling domestic disorders peaked in the autumn of 1884 when troops suppressed a large popular uprising in Chichibu, west of Tokyo. That October a 5,000-man-strong peasant army protesting usurious interest rates and demanding lower taxes and debt relief attacked government offices and moneylenders. In early November government troops used overwhelming force to restore order and shatter the popular rights movement, whose members disbanded rather than risk being labeled traitors for supporting insurrections. By that time, the army was engaged in reorganizing its basic force structure and command and control apparatus.