After 1941, the Balkans provided a much-required supply of natural resources for the Reich. One source, citing post-war reports from the Nuremberg trials, stated the Balkans provided “50% of petroleum, 100% of chrome, 60% of bauxite and 21% of Copper” for the German war machine. To protect both this vital source of resources and the lines of communication for its substantial occupation forces in Greece, Germany had some 18 Divisions in Yugoslavia, along with numerous other independent formations. This was an ulcer in the side of Germany as they sought to find troops to bolster their deteriorating position on the Eastern Front. These forces were still not sufficient to dominate the country and consequently they occupied the major urban areas and important communication nodes, while Partisan forces controlled the rugged countryside and were free to attack at will. The resulting situation for the Germans was dismal. In fact, in some areas morale was so low amongst German troops that many thought their prospects were better against the Russians and took the extraordinary move of volunteering for transfer to the Eastern Front rather than take their chances against the Partisans.

To Field Marshal Maximilian Freiherr von Weichs, who was not only the Commander of Army Group F responsible for Yugoslavia and Albania but also oversaw Luftwaffe General Alexander Löhr’s Army Group E in Greece, it was very apparent that he lacked the manpower and equipment to gain total victory in the field over the Partisan masses. The terrain was extremely well suited for guerrilla operations and very much favored the Partisans. He believed that the elimination of Tito, the personification of the Partisan movement and its center of gravity, would eliminate their will to fight. Hitler, who had personally ordered the elimination of Tito, shared this belief.

The task to locate Tito was assumed by several German intelligence organizations, including SS special operations expert Major Otto Skorzeny, operating independently on Hitler’s direct orders, and elements of the Brandenburg Division, the Abwehr’s special operations arm. The Brandenburgers had been involved on the attack on Jajce and now had their agents looking for clues as to Tito’s new location. The detailed task went to the Brandenburg Lieutenant Kirchner and his troops, and in a series of events to be discussed later, Tito and his headquarters were discovered from several sources to be in Drvar.

Planning and Preparation

Planning for the operation began in earnest. Field Marshal von Weichs signed the order on 6 May, and balancing synchronization of the operation with operational security, General Lothar Rendulic issued the Second Panzer Army order for Operation RÖSSELPRUNG two weeks later, on the 21st of May, allowing only three full days for subordinates to conduct battle procedure. Given potential security leaks in the form of Partisan agents, this was a prudent move. Rendulic, whose Second Panzer Army paradoxically did not include any panzer divisions, directed that the XV Gebirgs (Mountain) Army Corps, commanded by Lieutenant-General Ernest von Leyser, was to execute the operation.

A heavy bombardment of Partisan positions in and around Drvar by Fliegerführer Kroatien (Air Command Croatia) aircraft was to precede a parachute and glider assault by 500 SS Fallschirmjäger Battalion whose task it was to destroy Tito and his headquarters. Concurrently, XV Corps elements would converge on Drvar from all directions, in order to linkup with 500 SS on the same day, 25 May 1944. Speed, shock and surprise were key for the paratroopers of 500 SS to accomplish their mission.

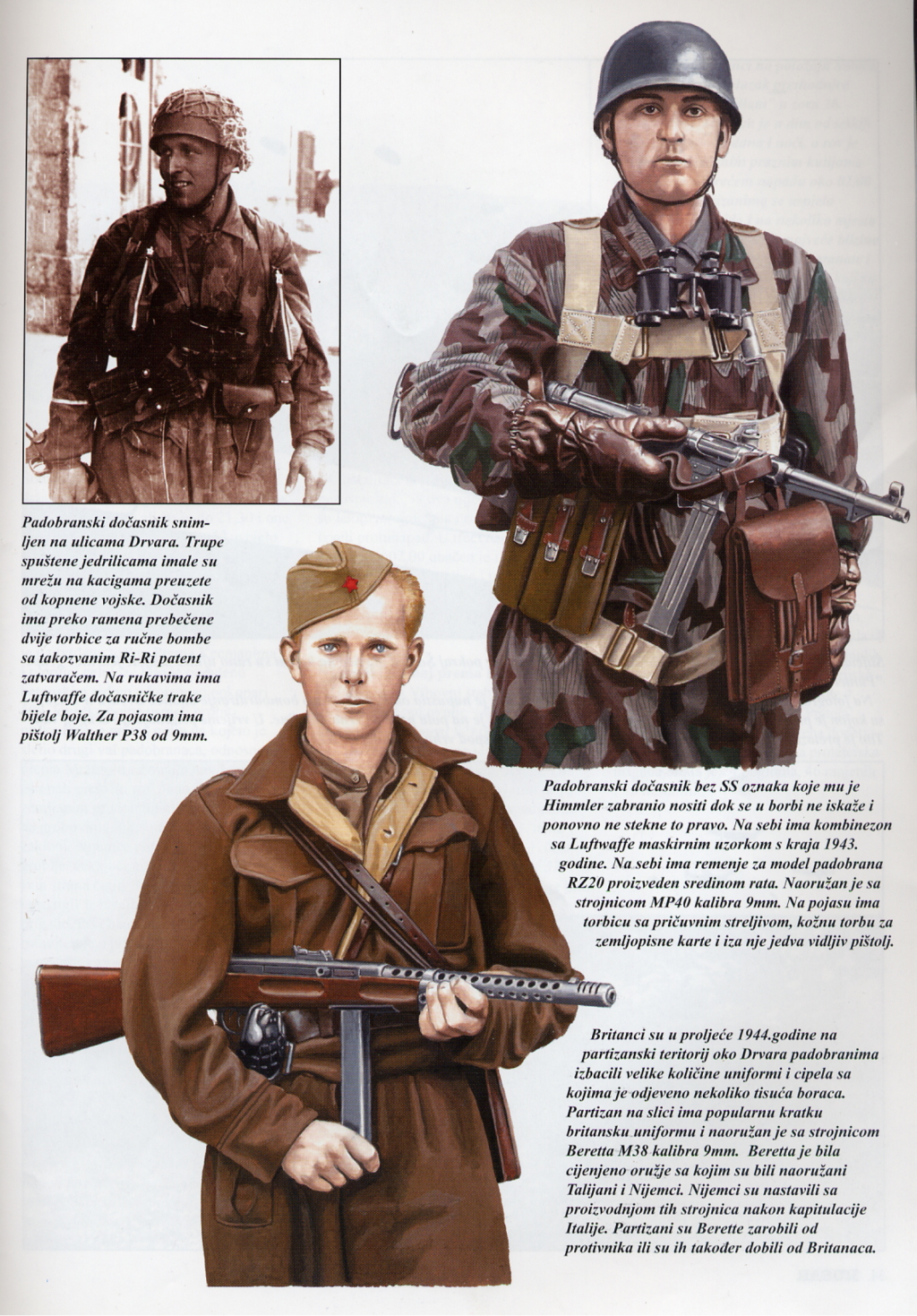

500 SS Fallschirmjäger Battalion was a relatively new unit. It was formed in the autumn of 1943 by direction of Hitler’s headquarters for the purpose of performing special missions. Sometimes referred to as a penal unit, it included many volunteers but for the most part initially, the enlisted ranks came from ‘probationary soldiers’. These were soldiers and officers who were serving sentences for minor infractions of a disciplinary instead of a criminal nature, imposed in the draconian environment of the Waffen SS. Dishonored men of all ranks of the SS could redeem themselves in this battalion and once joined had their rank restored. The unit conducted parachute school at the Luftwaffes’s Paratroop School Number Three near Sarajevo, Yugoslavia in November and finished in Papa, Hungary, early in 1944, as the school relocated there. After training was completed the unit participated in several minor Partisan drives before returning to its training grounds on the outskirts of Sarajevo in mid-April and remained there under strict security measures. While there, the 27-year-old SS Hauptsturmführer (Captain) Kurt Rybka took command of the battalion.

Rybka received an outline of the operation on 20 May and more detailed orders the following day. Realizing there were not enough gliders or transport aircraft to deploy 500 SS in one lift, he devised a plan where 654 troops would conduct the initial assault at 0700 hours, and a further 220 would reinforce as a second wave some five hours later. The intelligence picture that was portrayed to him was based on available sources, and recent air photos were used to aid in the planning. The suspected location of Tito’s headquarters, a cemetery on dominating ground, was given the codename ‘Citadel’ and the important crossroads in town was entitled the ‘Western Cross’.

The town was to be secured by 314 parachute troops. They were split into Red (led by Rybka), Green, and Blue Groups and were based on elements of the unit’s three rifle companies. Another 354 troops, based on remaining members of the rifle companies and the heavy weapons company, were split into six assault groups for specific missions. Panther Group of 110 soldiers, the largest, was to capture Citadel and destroy Tito’s headquarters. Greifer Group of 40 soldiers was to destroy the British military mission. Sturmer Group of 50 men was to destroy the Soviet military mission. Brecher Group of 50 men was to destroy the U.S. military mission. Draufgaenger Group was to capture the Western Cross and the suspected nearby Partisan communication facility. Of the 70 personnel in Draufgaegner Group, 40 belonged to the Brandenburg Benesch Group (some of whom were Chetniks and other local Bosnians) and six came from an Abwehr detachment commanded by Lieutenant Zavadil. These attachments were given specific intelligence collection, translation and communication tasks. Beisser Group of 20 soldiers was to seize an outpost radio station, then assist Greifer group. Finally, the second wave, base on the Field Reserve Company (basically the training company) and the remainder of the unit was to insert by parachute at 1200 hours.

For security reasons, the Battalion’s soldiers were not briefed on the operation until several hours before it was launched, but preliminary moves began on 22 May as the unit, dressed in non-descript Wehrmacht uniforms for security reasons, was transported by truck to three assembly areas, Nagy-Betskerek, Zagreb and Banja Luka. There they linked up with their Luftwaffe transport from Fliegerführer Kroatien, some of which had been brought in from France and Germany specifically for the operation. The 1st and 2nd Squadrons of Towing Group 1, and 2nd and 3rd Battalions of Air Landing Group 1, all with 10-passenger DFS 230 gliders and towed by either Hs 126 or Ju 87 (Stukas in a towing role) aircraft, would transport the glider-borne force. The 2nd Battalion of Transport Group 4, with about 40 Ju 52 transports, would deliver the parachute force. By 24 May, battle procedure was complete.

Partisan Disposition

German intelligence claimed about 12,000 Partisans were active in the area of operations, but Yugoslav sources place this number around 16,000, not including auxiliary support, schools, or members of the SKOJ (Communist Youth League of Yugoslavia). Immediately surrounding Drvar were the First (Nikola Tesla) and Six Proletarian Divisions of the First Proletarian Corps, with the Corps HQ based six kilometres to the east in Mokronoge. Of immediate concern was the Third Lika Brigade of the First Division stationed five kilometers south of Drvar in Kamenica, whose four battalions of were the most potent reaction force.

Within Drvar itself there was a mixed bag of military liaison missions, support and escort troops and both the Supreme Headquarters of the NOVJ and the Central Committee of the Yugoslav Communist Party. The Central Committee of the Communist Youth League of Yugoslavia was located in town, and had just held a congress of over 800 youths in attendance, some of whom were still in the process of departing. As well, the AVNOJ (Anti-Fascist Council of the National Liberation of Yugoslavia) had their headquarters on the outskirts of town and in the nearby village of Sipovljani there was the Partisan officers’ school with about 130 students. The Soviet Union, Britain and the United States all had military missions to Tito’s headquarters in some of the adjoining small villages. Finally, Tito’s Escort Battalion of three companies, two of which were with him, was present to provide personal protection to the Marshal and the various headquarters and missions.

Tito’s personal headquarters was initially located in a cave immediately north of Drvar and overlooked the town. When rumors surfaced that this location had become compromised, he moved his main headquarters to another cave in the town of Basasi, some seven kilometres to the west. His Drvar cave was used primarily during the day and he would return to Bastasi at night for security reasons. The location the Germans believed housed his headquarters, the cemetery at Slobica Glavica (Objective Citadel), was, in fact, sparsely manned.

Tito’s birthday was the 25th of May. On the evening of the 24th, a celebration was held in Drvar, and, due to the festivities finishing late, Tito decided to spend the night in his Drvar cave. Despite his initial concerns that caused him to relocate to Bastasi, he felt confident all would be quiet. It almost proved to be a fatal error.

The Battle

Tito, still somewhat sluggish from the previous evening’s celebration, awoke to the attack on Drvar. Operation RÖSSELPRUNG began according to plan on 25 May with a preparatory aerial bombardment of suspected Partisan location in Drvar, including the cemetery. This bombardment was to begin at 0635 hours and consisted of five squadrons of Ju 87 Stuka dive-bombers, older He 46 medium bombers, and Italian made Ca 314 and Cr 42 medium-bombers. It appears that the plan was closely followed. P-Hour began at 0700 hours. Although dense smoke from the bombardment reduced visibility, most pilots were able to orient themselves on the Western Cross and land gliders or drop their paratroops relatively close to designated objectives. Several gliders did land off course, including one in front of the main headquarters cave in Bastasi, where members of the Escort Battalion immediately killed the occupants before they could exit. Between two and four others landed in Vrtoce and the occupants had to fight their way into Drvar. German sources claim the parachute jump was made at 60 to 75 metres above ground level, but pictures taken from the ground of the jump indicate the it was somewhat higher.

Once on the ground, the Fallschirmjägers quickly seized control of Drvar. Panther Group, supported by Red Group, rapidly overcame token resistance at the cemetery and Rybka established battalion headquarters behind its walls. The only forces of consequence located there were the crews manning three anti-aircraft machine guns, of which two escaped. Needless to say, neither Tito nor his headquarters were found. Greiffer and Brecher Groups came up empty handed as the British and American missions were not present in their accommodations. Elements of Sturmer Group landed in a field immediately south of the cave and came under fire from Escort Battalion members positioned in the high ground surrounding Tito’s location. The most intense fighting was with Draufganger Group in the area of the Western Cross who assaulted what they believed to be the Partisan communications center, but was in fact the office building for the Communist Party’s Central Committee. After intense close quarter combat against fanatical resistance, the building was basically leveled with satchel charges.

Also subject to very fierce fighting were Blue and Green Groups, who were attempting to establish a cordon in the eastern part of town, where most of the population was located. Although not mentioned in German reports, Yugoslav accounts proudly cite a Partisan counter-attack by four captured Italian CV-34 tanks. Not inflicting any noteworthy damage, three tanks were quickly disabled and the remaining one escaped to Bastasi. Also creating a problem for the Germans, especially in the more populated areas, was resistance from the members of the Communist Youth League of Yugoslavia who remained in Drvar and whose enthusiasm in taking up arms (whatever were available) against the attackers could explain some accounts of spontaneous uprisings.

Immediately upon realizing the nature of the attack, the candidates from the officers’ school marched to the sound of gunfire. Armed with only pistols and the odd rifle, they split into two groups. The smaller group crossed to the north side of the Unac River and advanced west along the rail line with the aim of protecting Tito’s headquarters. The larger group, bolstered by the retrieval of several misdirected drops of German ammunition and arms, attacked Green and Blue Groups in their eastern flank beginning at approximately 0800 hours. Although the officer candidates suffered severe casualties, the pressure of their attack on this flank was maintained throughout the day.

By about 0900 hours, the Germans had secured the majority of Drvar, but they still had no trace of Tito. Before the operation, every Fallschirmjäger was issued with a picture of him[36] and they now went door to door, brutally questioning those civilians they could find. There are many Yugoslav based stories of German atrocities against the civilian population at this point in the battle, including herding people into houses to be burned alive, but it is difficult to determine where the Germans would find the time to do this based on the influence of other events.

By mid-morning it became apparent to Rybka that Partisan resistance was concentrated to the north in the area of the headquarters cave. He surmised that there must be something to protect in this area, and if Tito was in Drvar this would be his likely location. Launching a red flare as a pre-arranged signal, he rallied his soldiers for an attack on the new objective. Around 1030 hours he launched a frontal attack across the Unac River, supported by at least one MG-42 medium machine gun firing into the mouth of the cave. They made it as far as the base of the hill leading up to the cave, less than fifty metres from its mouth, before being repulsed. The Fallschirmjägers from 500 SS, already parched from a lack of water, had suffered severe casualties.

Concurrent with the mounting and execution of this attack, more Partisan forces were beginning to converge on Drvar. From the west and southwest came three of the battalions of the Third Brigade of the Sixth Lika Division. One battalion attacked directly towards the German position at the cemetery while the other two swung around to the west through Vrtoce to hit the Germans in the western flank with a view to relieve pressure on the cave area.

At approximately 1115 hours, during a lull in the fighting and after the attack had been repulsed, Tito managed to escape from the cave. This act has been inaccurately described in many accounts. After the first attack failed, Tito, escorted by several staff, climbed down a rope through a trap door in a platform at the mouth of the cave. He then followed a small creek leading to the Unac River, then diagonally climbed the heights to the east of the cave, a route which would provide cover for most of the way. From the Klekovaca ridge overlooking Drvar, he began his withdrawal east to Potoci.

1200 hours was P-Hour for the reinforcing second wave of 220 Fallschirmjägers who jumped in two groups just to the west of Objective Citadel. Their drop zone was situated within Partisan fields of fire and thus the wave suffered many casualties as they hit the ground. Newly armed with the remaining reinforcements, Rybka attempted another assault, but by now the pressure on his flanks was too great and the attack again floundered. Fighting continued throughout the afternoon with both sides taking heavy casualties. By late afternoon Rybka, realizing that the capture of Tito was improbable at this point and that the linkup with ground forces would not happen as planned, ordered a withdrawal. He initially planned to have a defensive perimeter encompassing both the cellulose factory and the cemetery, but after realizing the extent of his casualties and his consequent inability to hold the large perimeter, he reduced his defensive position to include just the cemetery. At about 1800 hours, while withdrawing under fire, he was injured by a grenade blast and was out of the battle.

The withdrawal to the cemetery was done under considerable pressure. At least one group of Fallschirmjägers was cut-off and wiped out. By about 2130 hours, the remnants of the Battalion had consolidated in the cemetery. Partisan forces had the remnants of 500 SS completely surrounded. Throughout the night attacks against the German position continued. The fourth battalion of the Third Lika Brigade, which had arrived later than the other three and been kept in reserve, was launched with the remnants of the other three battalions against the cemetery. Elements of the Ninth Dalmatian Division joined the attacks at some point during the night, increasing the pressure. The Fallschirmjägers continued to hold their ground, but casualties were mounting. At 0330 hours the final Partisan attack was launched, breaching the cemetery wall in several locations, but the German defence held.

Throughout the day, the progress of the converging elements of XV Mountain Corps was not as rapid as had been planned. Unexpected resistance from I, V, and VIII Partisan Corps along their axis of advance greatly hindered their movement. Most post-operation reports cite extremely poor radio communications amongst the different elements, causing a plague of coordination difficulties. It would also appear that Allied aircraft, based in Italy, attacked the linkup forces with several sorties throughout the day, however air support from the Luftwaffe was also present throughout. In fact, an unarmed Fiesler Stork reconnaissance plane, initially intended to whisk Tito away once taken, was able to land and extract casualties, including Rybka.

After the last attack failed to penetrate the German defences and knowing that relief in the form of XV Mountain Corps was on the way, Tito ordered the Partisan forces to withdraw, and then made good his escape. Escorted by elements of the Third Krajina Brigade, he first went to Potoci, where he met up with a battalion from the First Proletarian Brigade, and, after discovering German troops in force in the area, made his way to Kupres. In the Kupres Valley, a Soviet Dakota aircraft stationed at a Royal Air Force base in Italy and escorted by six American Aircraft picked him up on 3 June and took him to Bari, Italy. On 6 June, a Royal Navy destroyer delivered him to the Island of Vis, along the Dalmatian Coast, to re-establish his headquarters.

The remnants of 500 SS were to spend the rest of the night of 25/26 May in their hasty defensive positions. They received some support at 0500 hours as a German fighter-bomber formation attacked the withdrawing Partisans. At 0700 hours, the unit finally established radio contact with the Reconnaissance Battalion of the 373rd Division but physical linkup in Drvar with XV Mountain Corps did not occur until 1245 hours when the lead elements of the Second Battalion of the 92nd Motorized Grenadier Regiment arrived.

Despite not eliminating Tito, the Germans were unwilling to admit defeat and viewed this operation as a success with blind arrogance. According to a self-congratulatory report from Second Panzer Army:

“The operation against the partisans in Croatia [this area of Bosnia was included as part of Croatia at this time] enjoyed considerable success. It succeeded in 1) destroying the core region of the communist partisans by occupying their command and control centers and their supply installations, thereby considerably weakening their supply situation; 2) forcing the elite communist formations (1st Proletarian Division and the 3rd Lika Division [incorrect designation] to give battle and severely battering them, forcing them to withdraw due to shortages of ammunition and supplies, and avoid further combat (the 9th, 39th and 4th Tito Divisions also suffered great losses); 3) capturing landing fields used by Allied aircraft, administrative establishments, and headquarters of foreign military missions, forcing the partisans to reorganize and restructure; 4) giving the Allies a true picture of the combat capability of the partisans; 5) obtaining important communications equipment, code keys, radios, etc. for our side; 6) achieving these successes under difficult conditions that included numerous enemy air attacks.”

The future commander of 500 SS was even more sanguine: “Overall the operation with its jump and landing was a success. Unfortunately Tito and the Allied military delegations managed to escape.” With an understanding of the German mission, this becomes a rather contradictory statement.

The overarching intent of Operation RÖSSELPRUNG was the elimination of Tito, the man who personified the Partisan movement. To the German high command, Tito was the center of gravity for the Partisans and his elimination would greatly diminish the resolve of the movement to continue. “Tito is our most dangerous enemy,” Field Marshal von Weichs was to claim before the operation. Despite the words of praise, the costly operation only netted the Marshal’s uniform, in for tailoring, a Jeep, which was a gift from the American mission, and three British journalists, one of whom later escaped. Even the intelligence information gathered, contrary to the above report, was not of much use. When the operation failed to eliminate Tito, it failed to achieve its underlying intent for being launched, and thus by no stretch can be considered to have achieved its purpose.

Ironically, Tito’s dramatic escape further solidified his deity-like stature amongst the Yugoslav population, and became part of the mythology surrounding this cult of personality. Although NOVJ headquarters, along with several other Partisan organizations, had their operations temporarily disrupted and several higher level personnel killed, they were quick to recover and set up in different locations. Drvar reverted to Partisan control within weeks.

Many accounts of `Rösselsprung’ state that SS-Fallschirmjäger-Bataillon 500 was `destroyed’ in the fighting, claiming that of the 874 men that had landed at Drvar only some 200 survived fit for service at the end of the battle, but this assertion needs to be differentiated. According to official German after-action figures dating from June 10, the battalion had 61 killed, 114 seriously and 91 lightly wounded and 11 missing, making for a total of 277 casualties. An earlier report from June 7 quoted even lower figures: 50 killed, 132 wounded and six missing, i. e. a total of 188. Even if one allows for the casualties suffered by the attachments (of the 36 glider pilots five had been killed and seven wounded; of teams Zawadil and Benesch two men had been killed and 24 wounded, etc) this is far from the reputed 650 casualties.

It continued throughout the rest of the war as the sole SS parachute unit, with its designation later changed to 600 SS Fallschirmjäger Battalion, but Operation RÖSSELPRUNG was to be its only combat jump of the war.