Walther von Lüttwitz

The major move by the right to overthrow the revolutionary government of the Soci left and replace it with a military dictatorship came during March 13–18, 1920 at Berlin. This was what has come down in German history as the Kapp Putsch, although his purely civilian part in it was not its most important factor. That belonged to a Regular German Army officer instead.

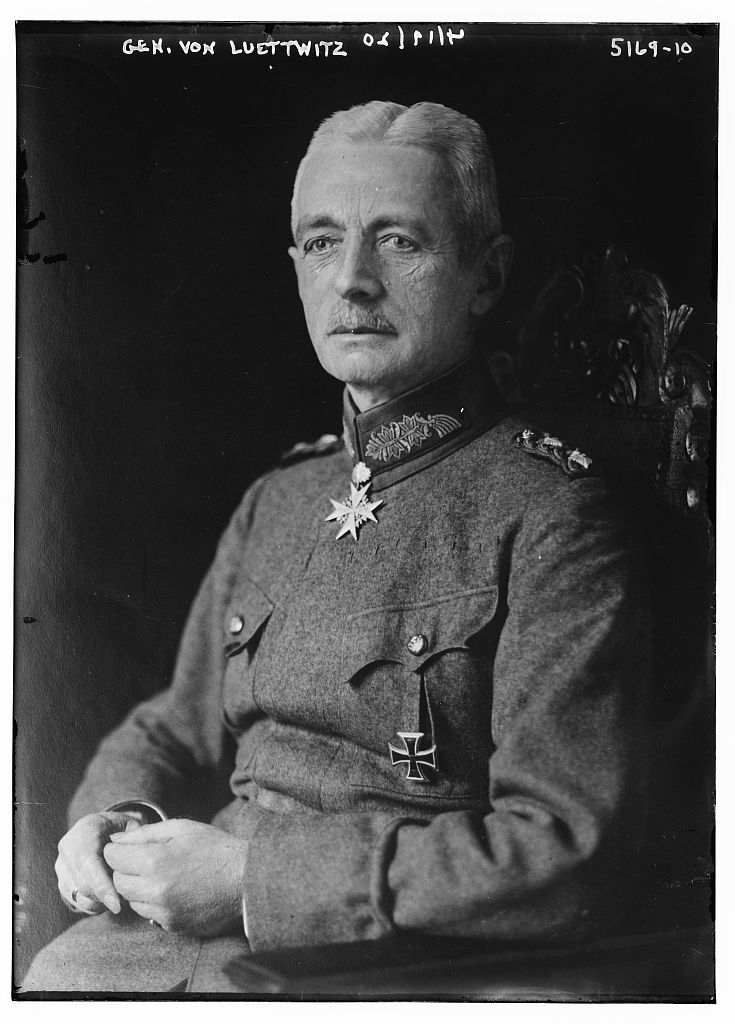

Gen. Walther von Lüttwitz

Gen. Walther Baron von Lüttwitz (February 2, 1859 to September 20, 1942) was born at Bodland near Kreuzberg in Upper Silesia, son of a head forest warden and levee overseer.

Commissioned an officer following his military training of 1878–87, von Lüttwitz graduated from the War Academy in 1890, serving at various postings during the next twenty-two years up to 1912, when he was appointed to the general staff at Berlin. His later commander, Imperial Crown Prince Wilhelm, described von Lüttwitz as “more a leader of men than army chief—more Blücher than Gneisenau.” Nevertheless, von Lüttwitz served as Little Willy’s own chief of staff in 1916 at Verdun, after having been the C.O. of 10th Army Corps during the Second Battle of Champagne in France.

In November 1916, he was returned to Army corps command of the 3rd, and during the Michael Offensive, he was awarded the Oak Leaves to his already given Blue Max, awarded for his leadership in the Battle of St Quentin/La Fère.

Postwar, on December 28, 1918, von Lüttwitz was named commandant of all military forces at Berlin, as well of the newly formed Freikorps units overall. During 1918–19, he earned the title “Father of the Freikorps” when he deployed them in place of the less reliable and politically Red-tainted Regular Army troops under his joint command.

With these forces, it was von Lüttwitz who defeated the Red Spartacist Revolt of January 1919 at Berlin, and the following May, the Soci government duly promoted him to command all Reich forces in case of more such risings or renewed war with the Allies. That July, however, he became a plotter to overthrow the very government that had just named him to defend it. When ordered to disband a pair of the most anti-government Marine FKs, Gen. von Lüttwitz instead commanded the Marinebrigade Ehrhardt Freikorps to occupy the capital and overthrow the Soci government itself on March 13, 1920.

As the troops carried out their orders, Gen. von Lüttwitz brought into his leadership circle, among others, Ludendorff and Reichstag Deputy Wolfgang Kapp. Their joint goal was to set up an authoritarian regime that would restore the old Bismarckian Reich’s 1871 federal establishment, although not necessarily that of any monarchs per se.

The leaders met at the Brandenburg Gate on the 13th to launch the coup, and they quickly occupied the downtown central government ministries quarter. Deputy Kapp declared himself the new Reich chancellor, and under him von Lüttwitz as his Minister of Defense.

Kapp located his new government in the Old German Reich Chancellery after the ousted Socis fled Berlin altogether, first to Dresden and then to Stuttgart, in disarray.

Gen. von Seeckt infamously refused to defend the ousted government by firing on the plotters, waiting to see which side would prevail.

This turned out to be the government’s own civil servants who refused to work with the plotters, and also Berlin’s workers, who called and enforced a general strike of all transportation that simply shut down Reich Capital Berlin. The revolt collapsed.

Gen. von Lüttwitz resigned his commands on March 18, 1920 on the revolt’s sixth day, seeking political asylum in Hungary, returning via an amnesty to Germany in 1924. He died at the age of eighty-three at Breslau on September 20, 1942, when it seemed most likely that then Nazi Germany would win both the Battle of Stalingrad and also World War II.

Kapp fled to Sweden, returning from exile two years later in April 1922 to stand trial at Leipzig, but he died of cancer while in police custody before he could be tried.

Mrs. Ludendorff as Insider Eyewitness to the Kapp–Lüttwitz Putsch (My Married Life)

After Ludendorff’s return from Sweden, [where he had written his memoirs during his brief 1918–19 exile] we lived in the Hotel Adlon in Berlin … Herr Adlon … had the tact to give us a room with a separate exit on to the Wilhelmstrasse.

By this means, we avoided contact with the officers of the Entente, [whose Berlin headquarters it also was] and in all the months I was there, we never encountered them. [Later, they moved to a flat] with a view of the Tiergarten.…

There were conferences in all the rooms, and all those who later took part in the Kapp revolt were in and out of our house: Gen. von Lüttwitz, Gen. von Oven, Col. Bauer, Capt. Pabst, and many others.… Kapp himself came often, so that I got to know him.

He was a man with an insinuating personality—highly gifted as an orator—so that people listened eagerly to his clever speeches, and yet how pitifully he failed!… What was planned and contemplated was a dangerous game.…

Later—when I realized the true state of things—I never understood how it was that Ludendorff was the only person to be snared by the alluring eloquence of these men.… It is inconceivable that a man like him—with his scientific outlook and solidity—should have taken part in an affair that was deficient in any and every detail of organization.

When the Kapp conspirators had fled to the four winds, they left behind them an office that was conducted with almost criminal carelessness and entirely devoid of system.… Ludendorff never possessed any knowledge of human nature, otherwise he could never have been at the mercy of those influences that brought about his downfall. Even quite dubious elements did not hesitate to approach him.…

Even before Ludendorff left Berlin, we were already in grave difficulties, and our lives were threatened. Capt. Ehrhardt placed at our disposal a bodyguard of 24 men—splendid fellows!—devoted body and soul to their leader.

They protected us faithfully—and it was imperatively necessary—since the excitement of the populace knew no bounds, and all their rage and all their hate was concentrated on Ludendorff.

His friends saw to it he escaped from this danger, and provided him with a refuge in a Bavarian castle.

Remarkably, he was not brought to account by the restored Soci government afterwards.