Like many tribal societies, the ethnic groups of Ethiopia put a strong emphasis on martial ability. Boys were trained from early childhood in the use of the sword, spear and shield. Every man yearned to own a gun, not just for what it would do for him on the battlefield, but also for hunting.

The Italians faced an Ethiopian army larger and more organized than in all of its recent history. Menelik had centralized and streamlined the taxation system, bringing in more goods to the central government. This allowed Menelik to keep a larger standing army, and support a huge temporary army at need. Most taxes were in kind – food or labour that went directly to support the soldiers. Menelik also ordered an extensive geographical survey in order to increase revenue, and to identify land that could be given to soldiers as a reward. His government also enjoyed the revenue from customs duties on ever-increasing international trade.

Mobilization and logistics

While the emperor maintained only a relatively small standing army, the entire countryside could be mobilized when a Negus ordered a kitet, or call to arms. This was made by proclamations in marketplaces and other gathering spots, and large negarit war drums were beaten to alert outlying farms. One even acted as a platform for the messenger, who stood on an upturned drum and read the proclamation while a slave held his lance and robe next to him as symbols of his rank. While the king was not always in full control of his territory, `beating the kitet’ was generally effective; it usually summoned men to fight against a common enemy, and always offered a chance for plunder and prestige. The Ethiopian army on the march looked more like a migration. Many warriors brought their families along, and wives and children would cook and gather provisions and firewood. During the march there were no stops until a camp was found for the night. The was assembling might run into difficulties of supply, especially considering that some regions he planned to march through were suffering from famine, so he ordered depots of food to be placed at regular intervals along the lines of march. This allowed Menelik to wait out the Italians on a couple of occasions.

This need for strategic speed affected how the Ethiopians made war. They avoided long conflicts in favour of big showdown battles in which they could destroy the enemy army and force favourable terms from the enemy commander. Drawn-out campaigns could prove counterproductive, since the army would have to ravage the very land they sought to conquer, forcing the inhabitants to flee. During Menelik’s long wait before Adowa the area was picked clean of food and most of the trees were chopped down for firewood. Shortages of ammunition, and the often fragile coalitions among the leaders, also encouraged quick campaigns.

To aid the advance, teams of workmen moved ahead of the main army clearing the way of trees and stones and searching out the best passes through the mountains. The Negus Negasti kept a group that outsiders called the `Royal Engineers’, but while some were undoubtedly skilled at complex operations such as building bridges, most were simply labourers.

Tactics

Ethiopians favoured a half-moon formation in order to outflank and envelop an enemy, although extreme terrain often made this impossible. Despite having a general plan, warriors fought more or less as individuals, advancing and retreating as they saw fit. Chiefs only had a loose control over their men, and never kept them in close formation except for the final charge, when everyone bunched together and hurried to be the first to reach the foe. Considering the lethal effectiveness of late 19th-century rifles, this loose mode of fighting was actually in advance of its day. The Ethiopian tendency was to get in close to ensure a good shot, although rushing en masse when the enemy appeared weak did lead to great losses. The Italian army, especially the ascari, showed good discipline under fire, and inflicted heavy casualties on the Ethiopians; the majority of these tended to be suffered during the final rush. When charging, the Ethiopians used various battle cries depending on their origin: the Oromo shouted `Slay! Slay!’, while warriors from Gojjam cried `God pardon us, Christ!’, and those from Shewa rallied to the call `Together! Together!’

The Ethiopians had no formal medical corps. Healers trained in traditional medicine followed the army, but were too few to care adequately for the huge numbers of casualties. Still, traditional healers did the best they could at setting limbs and cleaning out wounds. One method for sanitizing gunshot wounds was to pour melted butter mixed with the local herb fetho (lapidum sativum) into the wound. In battle the warriors’ families cared for the wounded, collected guns from the fallen to distribute to poorly armed warriors, and fetched water for those wealthier warriors had servants to carry their equipment and mules or horses to ride. All these extra people and animals had to be fed, increasing the need to keep mobile. While some food was carried by the men themselves or on muleback, the army was expected to live off the land, and foragers spread out over a large area. The central highlands of Ethiopia are green and filled with game, so as long as an army kept moving it could feed itself, and, being relatively unburdened, it could move quickly. If it stopped for long, however, it would soon starve; this was a major problem if the army had to besiege a fortification, or – as in the run-up to Adowa – wait for an enemy to make the first move. Menelik realized that the large force he fighting. This last detail was important; at Adowa, Itegue Taitu had at least 10,000 women bringing water to the warriors, while the Italians suffered from thirst throughout the day.

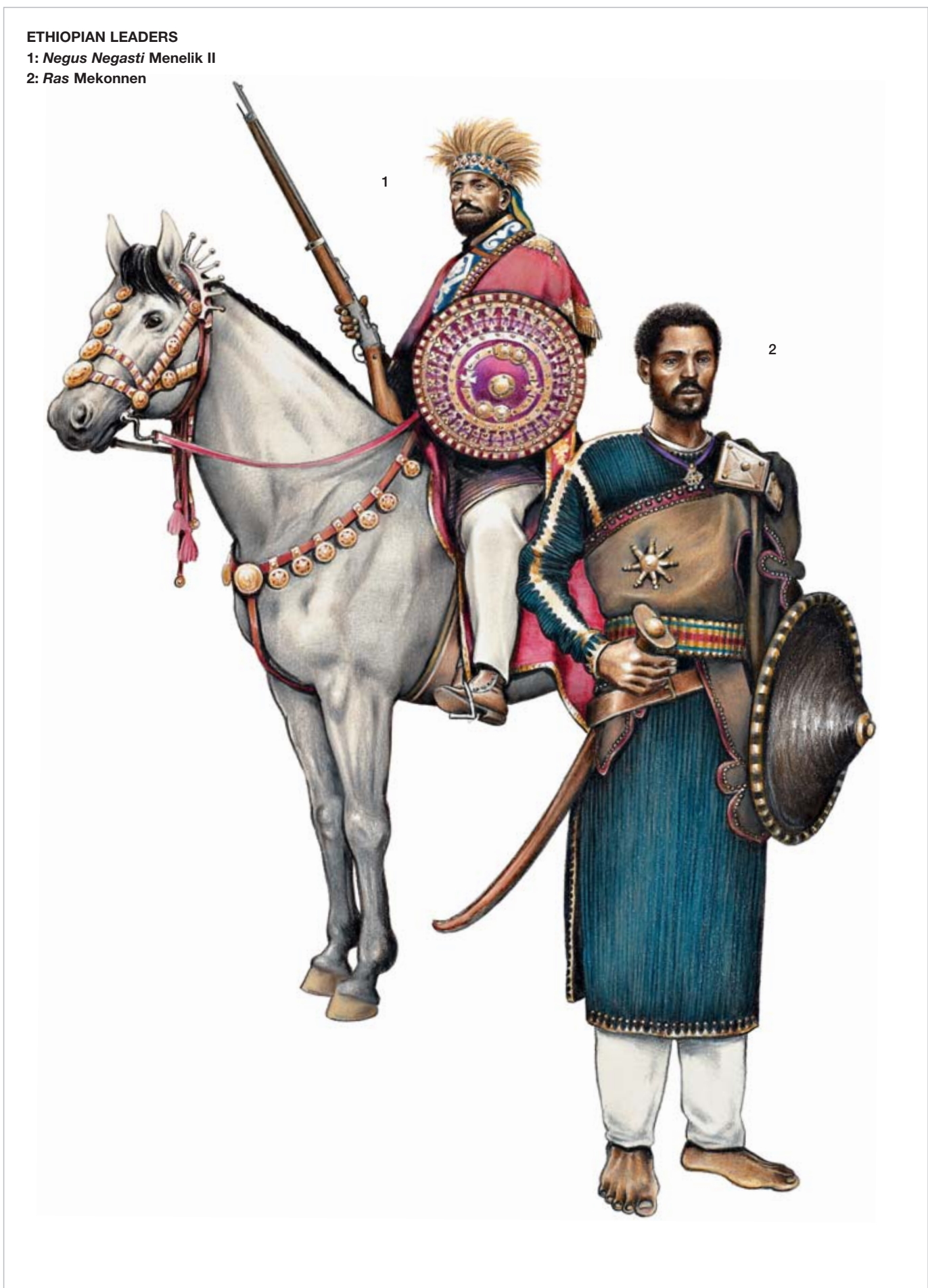

The Ethiopians lacked uniforms; common warriors wore their everyday clothing – generally a white, cream, or brown length of cotton called a shamma that was wound around the body in various ways. Chiefs and higher nobility wore a variety of colourful garments, including the lembd, a ceremonial item vaguely resembling the cope or dalmatic of Christian churchmen. If a man had slain a lion during his career, his formal clothing could be embellished with the lion’s mane.

Rifles

Despite Western preconceptions, and the employment of antique firearms by the poorest warriors, the majority of Ethiopians were armed with large-calibre, breech-loading, mostly single-shot rifles no more than 30 years old since they had first appeared in Western armies. It is estimated that Menelik’s army may have had as many as 100,000 of such weapons in 1896. Until the collapse of diplomatic relations he had been able to purchase large numbers of rifles from the Italians, and also from the Russians, French and British. After Italian sources dried up Menelik strove to increase his other imports, and a key figure in this trade was Ras Mekonnen of Harar, a city in eastern Ethiopia with trade links to the Red Sea. Individual chiefs also stockpiled arms, and issued them to their best warriors in times of need.

The types used by the Ethiopians included the elderly British 1866/67 Snider – an 1856 Enfield muzzle-loader converted into a single-shot breechloader. Used on the British Magdala expedition of 1867-68 against the Emperor Tewodros II, it had a massive 14.6mm calibre and a hinged breech action. However, the Ethiopians also had considerable numbers of the superior 1871 Martini-Henry – the classic British single-shot, lever-action, falling-block weapon of the colonial wars, firing 11.43mm bullets. The French 1866 Chassepot was another second-generation breechloader, a bolt-action, single-shot weapon taking 11mm paper and card cartridges; but again, the Ethiopians also had larger numbers of more modern 1871 Le Gras rifles, in which the Chassepot’s paper cartridges were replaced with 11mm brass rounds. Menelik’s warriors even had some 1886 Lebel 8mm bolt-action magazine rifles; with eight cartridges in the tubular magazine below the barrel, one in the cradle behind the chamber and one `up the spout’, these took ten rounds. The Lebel’s smaller-bore, smokeless-powder ammunition was the most advanced in the world (all the other types took black-powder rounds, which produced a giveaway cloud of white smoke and fouled the chamber fairly quickly with continuous firing).

The Peabody-Martini was an 1870 Swiss modification of an 1862 Peabody design from the United States. Widely manufactured across Europe, it had a single-shot, falling-block action in various calibres from 10.41mm to 11.43 mm. Probably the single most common rifle in Ethiopian use was the `rolling-block’ Remington, another American design very widely built under licence in the 1860s-80s, in calibres up to 12.7mm (.50 calibre). The Winchester 1866 was a lever-action 11.18mm calibre weapon with a tubular magazine taking 12 rounds; several later models used a box magazine. The Russians had supplied the Ethiopians with a fair number of US-designed, Russian-made Berdan 1864 and 1870 rifles; both were single-shot 10.75mm weapons, the 1864 model with a hinged `trapdoor’ breech and the 1870 with a bolt action. Sources also mention German Mausers, most likely the 11mm single-shot, bolt-action 1871 model. The Ethiopians also had some examples of the Austrian 1878 Kropatschek, an 11mm bolt-action repeater with an eight-round tubular magazine.

This wide variety of rifles and calibres inevitably created local shortages of ammunition. Menelik instituted a quartermaster system, and individual leaders may have helped supply individuals who were short of cartridges, but in general each man was expected to supply his own (and probably `collected his brass’ for artisan reloading). Cartridges were so valuable they were often used as currency; being hoarded, they tended to be older than was ideal, but Menelik and other leaders strove to purchase as much new ammunition as possible, and it appears that his forces at Adowa were well supplied. Still, out of habit the Ethiopian soldier conserved his ammunition, preferring to get up close before firing. Wylde noted they `made good practice at up to about 400-600 yards, and at a short distance they are as good shots as any men in Africa, the Transvaal Boers not excepted, as they never throw away a cartridge if they can help it and never shoot in a hurry’.

Traditional weapons

Despite the wide availability of firearms, many Ethiopians still went into battle with more traditional weapons. The shotel was the favoured type of sword, a heavy steel weapon curved like a scimitar, but with the sharpened edge usually on the inside of the curve so that the warrior could stab around the edge of an opponent’s shield. It was carried slung on the right side, so that the left (shield) arm had a full range of movement. Steel-headed spears were pretty much universal among men and boys for defending their flocks from wild animals; generally about 6ft long with a leaf-shaped head, they could be thrown, but were more often used for thrusting. Small shields completed an Ethiopian warrior’s kit. Styles varied among the tribes, but the most common was a circular, conical shield made of hide and covered on the front with coloured cloth such as velvet. Many were decorated and strengthened with strips of brass, tin or more valuable metals; a shield was an easy way for a warrior to show off his wealth and status, and many were quite elaborate.

Cavalry was common in the Ethiopian lowlands, and the horsemen of the Oromo were especially renowned. Horses were useful and acted as a status symbol, so every warrior wanted one. The Ethiopian horse is smaller than its European counterpart and can negotiate terrain that would stop a European steed. Nevertheless, Ethiopia’s mountainous terrain and dense thickets of thorn-bushes often meant that battles had to be fought on foot. Weaponry for cavalrymen was identical to that for footsoldiers.

Artillery

The Ethiopians had 42 guns at Adowa. It is unclear what types of cannon were used, but sources agree that they were a mix of older guns bought or captured from various sources. They included Krupps, and mountain guns captured from the Egyptians when they tried to take Ethiopian territory in 1875 and 1876, or left behind when the Egyptian garrison evacuated Harar in 1885. One source describes the artillery as `of all calibres and systems’. There was a chronic shortage of shells, and thus crews had little chance to practise. While the Ethiopians were capable of bombarding a fort, as at Mekele, they had difficulty in manoeuvring guns and laying down accurate fire in broken terrain against a moving enemy; Italian eyewitnesses said that the Ethiopian artillery made a poor performance at Adowa.

More effective were the several automatic cannon that Menelik brought to Adowa. A detailed listing is unavailable, but Maxim weapons are mentioned, and perhaps six were 37mm Hotchkiss pieces. Produced by an American company from 1875, these were later licence-built in Europe, particularly France. Early versions were multi-barrel revolvers, fired by turning a crank like a Gatling gun; later models had a single barrel and were fed by a belt. These later-model `pom-poms’ fired both solid and explosive rounds, and were superior in range and accuracy to the Italian artillery.

THE MAHDIST CHALLENGE, 1890–94

SUDANESE MAHDIST WARRIORS

1: Baqqara cavalryman This warrior is protected by quilted armour under an iron helmet and long ringmail shirt; note too the extensive quilted horse-armour and leather chamfron. He is armed with a spear with a broad leaf-shaped head, and a kaskara sword and flintlock pistol carried on his saddle. The Dervishes plundered many Martini-Henry rifles from defeated Egyptian soldiers, but the only modern touch to disrupt the splendidly medieval impression created by this warrior is a holstered revolver at his hip.

2: Sudanese footsoldier This infantryman, too, wears quilted armour; while useless against firearms, this was still fairly effective against the spears and swords of the Mahdists’ tribal enemies. He is armed with a spear, and a kaskara sword carried in a crocodile-skin scabbard; the flared end of the scabbard is purely stylistic, as the blade has conventional parallel edges. His concave hide shield with a large boss and nicked rim is of a type common in the Sudan.

A challenge to the Italians came from the loosely structured Mahdiyya army in the Sudan. The Mahdi claimed to be the new prophet of Islam, and his devout followers drawn from disparate peoples made great gains against the British-sponsored Egyptians and neighbouring tribes. There had been a longstanding rivalry between these Muslim warriors and the mostly Christian Ethiopians. Emperor Yohannes campaigned against the Dervishes, but, while at first successful, he was defeated and fatally wounded at the battle of Metemma on 9 March 1889.

Although the Mahdi died in June 1885 the fight was continued by his successor, the Khalifa. Between 1885 and 1896, when the reconquest of the Sudan was undertaken by the Anglo-Egyptians.

The Mahdists fought the Italians for the first time at Agordat on 27 June 1890. About 1,000 warriors raided the Beni Amer, a tribe under Italian protection, and then went on to the wells at Agordat, on the road between the Sudan and northern Eritrea. An Italian force of two ascari companies surprised and routed them; Italian losses were only three killed and eight wounded, while the Mahdists lost about 250 dead. In 1892 the Mahdists raided again, and on 26 June a force of 120 ascari and about 200 allied Baria warriors beat them at Serobeti. Again, Italian losses were minimal – three killed and ten wounded – while the raiders lost about 100 dead and wounded out of a total of some 1,000 men. Twice the ascari had shown solid discipline while facing a larger force, and had emerged victorious. The inferior weaponry and fire discipline of the Mahdists played a large part in these defeats.

Major-General Oreste Baratieri took over as military commander of Italian forces in Africa on 1 November 1891, and also became civil governor of the colony on 22 February 1892. Baratieri had fought under Garibaldi during the wars of Italian unification, and was one of the most respected Italian generals of his time. He instituted a series of civil and military reforms to make the colony more efficient and its garrison effective. The latter was established by royal decree on 11 December 1892. The Italian troops included a battalion of Cacciatori (light infantry), a section of artillery artificers, a medical section, and a section of engineers. The main force was to be four native infantry battalions, two squadrons of native cavalry, and two mountain batteries. There were also mixed Italian/native contingents that included one company each of gunners, engineers and commissariat. This made a grand total of 6,561 men, of whom 2,115 were Italians. Facing the Mahdists, and with tension increasing with the Ethiopians, this garrison was soon strengthened by the addition of seven battalions, three of which were Italian volunteers (forming new 1st, 2nd and 3rd Inf Bns) and four of local ascari, plus another native battery. A Native Mobile Militia of 1,500 was also recruited, the best of them being encouraged to join the regular units. Like all the other colonial powers, the Italians also made widespread use of native irregulars recruited and led by local chiefs.

The first big test came at the second battle of Agordat on 21 December 1893. A force of about 12,000 Mahdists, including some 600 elite Baqqara cavalry, headed south out of the Sudan towards Agordat and the Italian colony. Facing them were 42 Italian officers and 23 Italian other ranks, 2,106 ascari, and eight mountain guns. The Italian force anchored itself on either side of the fort at Agordat, and from this strong position they repelled a mass attack, though not without significant losses – four Italians and 104 ascari killed, three Italians and 121 ascari wounded. The Mahdists lost about 2,000 killed and wounded, and 180 captured.

When the Mahdists launched raids across the border in the spring of 1894, the Italians decided to take the offensive and capture Kassala, an important Mahdist town. General Baratieri led 56 Italian officers and 41 Italian other ranks, along with 2,526 ascari and two mountain guns. At Kassala on 17 July they clashed with about 2,000 Mahdist infantry and 600 Baqqara cavalry. The Italians formed two squares, which inflicted heavy losses on the mass attacks by the Mahdists, before an Italian counterattack ended the battle. The Italians suffered an officer and 27 men killed, and two native NCOs and 39 men wounded; Mahdist casualties numbered 1,400 dead and wounded – a majority of their force. The Italians also captured 52 flags, some 600 rifles, 50 pistols, two cannons, 59 horses, and 175 cattle. This crushing defeat stopped Mahdist incursions for more than a year, and earned Baratieri acclaim at home. (In 1896 the Mahdi’s followers would make several more incursions into Eritrean territory, but without success. Fighting the Italians seriously weakened the Mahdiyya, and contributed to its defeat at the hands of Kitchener’s Anglo-Egyptian army at Omdurman in 1898.)