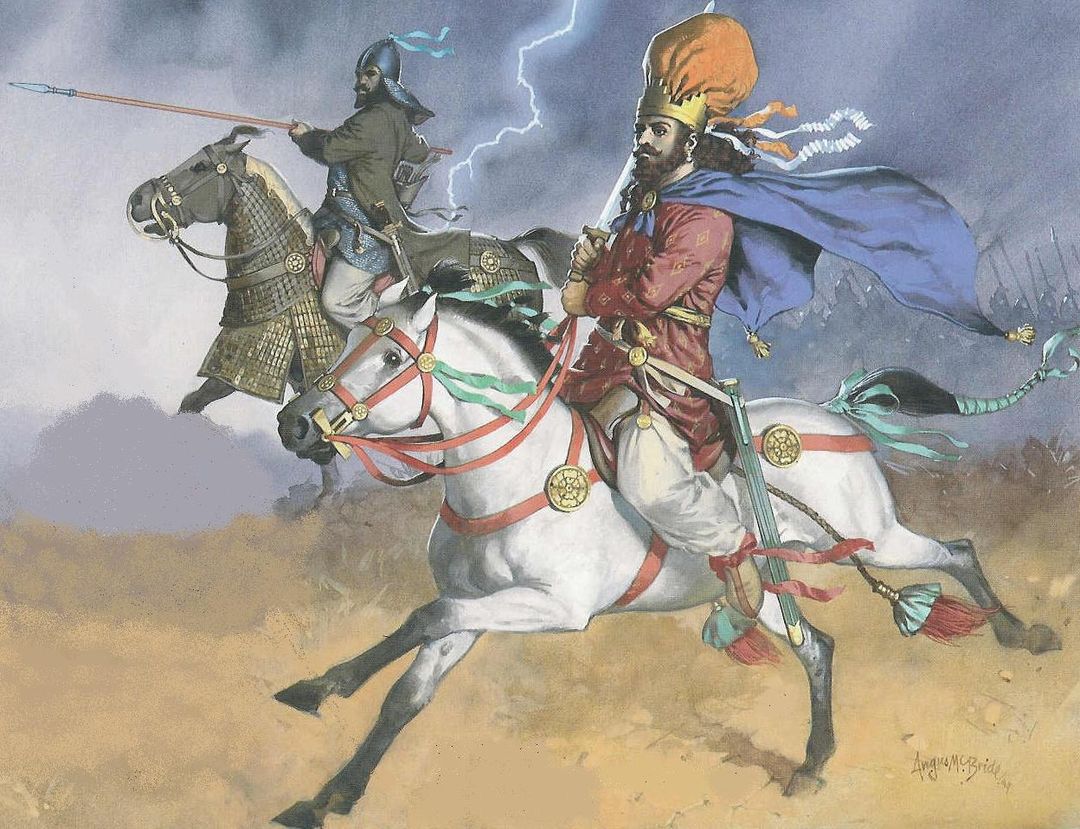

SHAPUR I

‘As for you wretched Syria, I weep for you with great pity. To you too will come a fearful attack by bow-shooting men, which you never expected to befall you. The fugitive of Rome will come, brandishing a great spear, crossing the Euphrates with many thousands, who will put you to the torch and maltreat everything….Having despoiled you and stripped you of everything, he will leave you roofless and uninhabited. Suddenly anyone who sees you will weep for you.’

The Thirteenth Sibylline Oracle (c. AD 253)

In 253 Roman forces had marched against one another in order to defend their choice of emperor. Valerian and his son, Gallienus, had been the victors in that relatively bloodless showdown, north of Rome. Bloodless it may have been, but Valerian had marched into Italy at the head of an army that he had been ordered to raise for a campaign on the upper Danube. Valerian had been given that job by emperor Trebonianus Gallus and once news of Gallus’ assassination reached Valerian, he had decided to move the Danube legions into Italy – he planned to take the throne away from the usurper, Aemilianus.

This crisis of succession and of legitimacy in 253 obscured the real danger. Not only had the Danube frontier been weakened by the removal of its troops to support Valerian’s claim on Rome, but in the east the ruin and destruction wrought by the energetic Shapur, ruler of Sassanid Persia, still smouldered.

Shapur Takes the East

The wicked Shapur of whom I have spoken succeeded him (Ardashir) and lived on for thirty-one years more, doing great harm to the Romans

Agathias 4.24

Valerian was not a young man, he was already fifty-eight when he took the throne and his son, Gallienus, was forty. In a way this provided the new emperor with a nominated successor and a loyal co-emperor from day one of his reign. This situation might have been able to provide the stability that the empire desperately needed, but Fate would cruelly intervene. Leaving his son to organise the defence of the west, the emperor set out immediately for Syria in order to restore the situation there. He would never return.

Antioch was the second city of the Roman Empire and the shock of its fall and destruction resonates in the writings from the time. Although Roman forces had been soundly beaten at the battle of Barbalissos in 252 and much of Syria then occupied and plundered by Persian raiding forces, it seems that its jewel, Antioch, fell to King Shapur a year later. The city was offered to the Persians by the traitor, Myriades. This man had been a wealthy senator who had been expelled from the city for embezzling funds that were destined for the chariot races. In revenge Myriades offered his services to Shapur and led the troops directly to the gates. The rich fled from Antioch at the approach of the Persians, leaving behind the restless masses who seemed to be quite content with a change of government.

Shapur had ordered a huge battering ram to be fashioned, its head was indeed in the shape of a ram and solidly made of iron. It was massive, and once it had served its purpose was dragged to the city of Carrhae and abandoned. A hundred years later this same ‘antique’ ram would be dragged to the city of Bezabde by the legions in order to dislodge the Persians from that city. The fall of Antioch must have been sudden and unexpected, Eunapius writes how a comic actor on stage within the city suddenly declared to his audience, ‘Am I dreaming or are the Persians here?’ His audience fled in terror as missiles rained down upon them, the houses and temples were plundered, inhabitants killed or taken into captivity and the city set on fire. The treacherous Myriades, history records, was executed by Shapur once the city had been captured.

Valerian mustered his Roman forces and fought the Persian garrisons left behind by Shapur. It must have seemed to the emperor that he was making light work of the Persian occupation and raiding troops, but the King of Kings was holding his elite cavalry forces in reserve further east. An unnamed Roman victory in 257 was even substantial enough to be commemorated on an issue of coins bearing Valerian’s name.

When Valerian discovered that Shapur was besieging Edessa with great difficulty in 260, he launched a military expedition to fight the Persians there. However, the plains around Edessa and Carrhae were much suited to Persian cavalry and in addition the Roman troops were far outnumbered. Not only that but the equites Mauri (the Moorish cavalry) were stricken with the plague. Suffering a terrible defeat in June of that year and forced to retreat behind the walls of Edessa, Valerian had run out of options. Persian inscriptions claim that the Roman force had numbered 70,000 and that a great number were captured and deported to Iran. The emperor decided to attempt negotiation, it was perhaps the only option left to him. Shapur insisted he leave Edessa to talk, accompanied only by a small retinue of advisors and officers. Upon receiving the Roman delegation, the ‘wicked and bloodthirsty’ king captured them all. Valerian, the emperor of Rome, as well as high ranking Roman senators, the praetorian prefect and many others, were all enslaved. No emperor had ever been captured by the enemy before; the news stunned Rome.

Free now to roam at will, Shapur attacked Syrian cities in a renewed military campaign, sacking Seleucia, Iconium, Nicopolis, Tyana and, once again, Antioch. The Persian army even reached Cappadocia. The Roman forces, smashed outside Edessa, were little match for the Persian army. There was some spirited resistance in Cilicia where a Roman general named Ballista rallied Roman stragglers and made attacks on the Persians, now divided into smaller, more mobile raiding parties. He was able to capture the harem of Shapur along with a great deal of booty and his troops were able to wipe out a force of three thousand Persians.

Shapur, realising he had outstayed his welcome, turned his forces east and headed for home. He first had to bribe the fierce citizens of Edessa in order that he might pass unmolested. Odaenathus, king of Palmyra, a wealthy caravan city allied with Rome, could not be bribed – and he harried the retreating Persians along the Euphrates river frontier. Thousands of prisoners were marched east by the Persians, fed on the bare minimum to support life and allowed to drink once a day, being driven to water by their guards like cattle. According to the writer Zonaras, at one point the retreating column reached a gorge impassable to Shapur’s baggage animals. The king ‘ordered the prisoners to be killed and thrown into the gorge so that when its depth was filled up with the bodies of the corpses, his baggage animals might make their way across.’

Of course Valerian was now also a prisoner. Accounts differ about how long he survived; Aurelius Victor claims that he was quickly hacked to death, but others insist the emperor lived out his life in servitude to Shapur. As a common slave, Valerian, a man in his sixties, was humiliated and forced to stoop and allow Shapur to step on his back to mount his horse. Lactantius claims that when Valerian eventually died, the Persian king had his body skinned. The old man’s skin was dyed with vermillion and then stretched upon a wall so that future ambassadors from Rome might look upon poor Valerian evermore as a symbol of Rome’s military vulnerability.

Had Valerian left no heir it is likely that a new round of civil wars would have torn through the empire. However, Valerian had entrusted the western half of the empire to Gallienus, his capable son and co-emperor. But if Romans had thought that the future could not get any worse, they were sorely mistaken.

The Era of Pretenders

Now let us pass on to the twenty pretenders, who arose in the time of Gallienus because of contempt for the evil prince.

Historian Augusta, Life of Gallienus 21

While Valerian spent his final years of freedom in the east waging war against the Persian army, his son Gallienus was no less busy on the northern frontier. German tribes beyond the Danube river were beaten back during the years 254 to 256, and once that frontier was secure, the focus shifted to the defence of the Rhine. Attacks came thick and fast. Although Gallienus claimed the title of ‘Germanicus Maximus’ for himself five times and issued coins celebrating his victories beyond the Rhine, he was soon back on the Danube (258). Yet, despite his furious fire-fighting Gallienus could not be everywhere at once and further west the Juthungi broke through the military frontier (limes).

From the North Sea, the river Rhine snaked southwards to provide a natural barrier against the German tribes to the east. Meanwhile, Italy, Pannonia and Thrace received the protection of the river Danube which ran from southern Germany eastwards to the Black Sea. North of this frontier, German and Sarmatian tribes squared off against the local Roman garrisons. However, these ‘wet’ frontiers, formidable natural moats that took great effort to breach, did not meet. This vulnerable gap at the headwaters of the Danube and the Rhine was kept free of German invaders with only a man-made defensive line. The modern-day German state of Baden-Württemberg represents the vulnerable provincial settlement known as the Agri Decumates that lay behind this frontier.

For the previous twenty years attacks had been frequent and punishing on this defensive weak point. At Castra Vetoniana (modern Pfünz) excavations seem to suggest that the soldiers of cohors I Breucorum had been so surprised in one attack that gate guards had no time to grab their shields. Repeated Germanic attacks eroded the military installations and their garrisons to a point that made the 259 invasion possible. The Juthungi descended on Italy and marched toward Rome where a hastily assembled army turned them back – they were defeated near Mediolanum (Milan) by the forces of Gallienus. The weakened sector of the frontier had exposed Italy to the ferocity of the northern tribes. Rome, a city without fortifications, had not felt this vulnerable since the first century BC.

Unsurprisingly, the Agri Decumates was hastily abandoned – that frontier was now considered untenable. Yet attacks continued relentlessly. The Alemanni invaded Italy in 260 while other raiders ravaged as far as Gaul and Spain. The northern borders were crumbling, as was confidence in the emperor Gallienus. Beleaguered provincials who were threatened with continued barbarian attacks, and some of the emperor’s own generals, had lost faith in Gallienus’ ability to defend the empire.

The Usurpers

The invasion of northern Italy and the abandonment of the Agri Decumates region, coupled with the Roman defeat at Edessa and capture of Valerian, triggered a wave of usurpers all eager to prove that they could do better. Although the Historia Augusta talks of twenty pretenders, there were in fact fewer serious contenders. First was Ingenuus, governor of Pannonia and Moesia, with plenty of legions at his command. He was defeated in battle at Mursa, northwest of modern Belgrade, by a Roman army led by one of Gallienus’ top generals called Aureolus. This seething frontier produced another discontented general, Regalianus, who was proclaimed emperor by the remnants of Ingenuus’ broken army in late 260. He was murdered by his own troops.

Syria had more right than most to be discontented and late in 260 the legions there threw their support behind Macrianus and Ballista, the two generals who had pulled together some kind of military response to the terrible Persian onslaught following Valerian’s capture. Macrianus was hailed as emperor by the eastern troops he commanded but being of advanced age and infirm, he passed that title to his two sons, known together as the Macriani. The two brothers were named Fulvius Iunius Macrianus and Fulvius Iunius Quietus. Proclaimed joint emperors and enjoying the support of the war-weary eastern provinces they planned to take control of the empire. Macrianus (the older of the two brothers) marched against Gallienus with an army numbering 45,000. Again the general Aureolus counter-attacked and in 261 his forces encircled the army of the rebels in Illyricum (the region of former Yugoslavia). The trapped legionaries suddenly switched sides and ended the rebellion.

Quietus, the younger of the Macriani, had remained in Syria with Ballista and both men had taken refuge within the city of Edessa. Here, Gallienus was able to call on Odaenathus, an ally in the east on whom he could depend. As the ruler of wealthy Palmyra, untouched by Persian aggression, Odaenathus commanded the premier fighting force on the eastern frontier. Following the earlier Palmyrene attacks on the Persian columns and the capture of Shapur’s harem, Gallienus had rewarded Odaenathus with the honorary title of dux Romanorum (‘regional commander’). Edessa was soon besieged by the Palmyrene prince who executed Quietus and Ballista once the city had fallen. He did this on behalf of Gallienus.

The eastern uprising had been quashed but plenty of bitterness and resentment circulated throughout the empire. Mussius Aemilianus was governor of Egypt and had been part of the Macriani revolt. Now he claimed the throne but like the Macriani, he was defeated in battle and executed early in 262.

Even Aureolus, the emperor’s trusted general, rebelled in 262 but he was forced to back down and make peace with his master. Unusually, the emperor let him retain not only his life but also his position and power. Perhaps he needed the military talent of Aureolus too much to have him executed.

Fragments of Empire

Upon the news of Valerian’s capture and enslavement, the governor of Lower Germany, Marcus Cassianus Latinus Postumus, rose in revolt against Gallienus. Postumus had ably dealt with a Germanic attack and on the strength of this victory, had his troops proclaim him emperor. In the autumn of 260 he marched to Colonia Agrippina (modern Cologne) where the young son of Gallienus, Salonius, had been installed as co-emperor with his father. Postumus refused to give up the siege of the city unless Salonius was handed over to him. Once the folk of Colonia Agrippina agreed to the demands, both the boy and his guardian were executed.

Unlike past usurpers who had usually gathered together a military force and then made a dash to Rome, Postumus seemed content to remain beyond the Alps. Using the Rhine legions, he was able to clear the western provinces of barbarians and in doing so he earned the loyalty of the British, Spanish and Gallic provinces. The governors and legionary commanders decided to recognise Postumus as the legitimate emperor over those territories. This was not a re-run of power-sharing between Clodius Albinus and Septimius Severus in 193, Postumus had, in a stroke, created an alternative Roman Empire, one based primarily upon the defence of the western provinces that was ruled from Augusta Treverorum (modern Trier). Postumus made it clear that he was satisfied with the western provinces and did not spoil for a fight, this was just as well, for Gallienus was struggling to cope with a series of usurpers from 260 to 262.

It was not until the spring of 265 that Gallienus felt confident enough to challenge Postumus and marched a Roman army deep into Gaul. An early victory led to the bottling up of Postumus within a city (possibly Lugdunum, modern Lyons) followed by a siege. While the emperor inspected the siege works constructed by his troops, a defender shot Gallienus in the back with an arrow, seriously wounding him. He was evacuated back to Rome in order to recover and although Aureolus was left in charge of the conflict he seems to have made some kind of deal with Postumus, lifting the siege and letting the usurper escape. The Gallic Empire was thereafter left unmolested by Gallienus who continued to face the inevitable distractions – the renewed invasions that would continue to batter what was left of the Roman Empire.

This break-away Gallic Empire survived as an independent state for the next fourteen years; it was made up of the three provinces of Gaul (Aquitania, Narbonensis and Lugdunensis), the two German provinces (Upper and Lower), the three Spanish provinces (Tarraconensis, Lusitania and Baetica), Raetia and the two British provinces (Superior and Inferior). Raetia was taken back by Gallienus in 263 and the Spanish provinces, along with eastern Narbonensis (that area east of the Rhône) were all recovered in 269. However, a measure of the Gallic Empire’s success can be gleaned not just from its relative longevity but also from the fact that all of its four emperors refused to march on Rome and they instead focused on protecting the territory from incursions beyond the Rhine. The third century ‘disease’, that of imperial succession by military assassination plagued the successors of Postumus just as it did Rome; all but the last of the Gallic emperors were murdered.

In a sense, the Gallic Empire depicts the Roman Empire cracking and disintegrating under pressure, and as events in Syria would soon show, it was not just the west that wanted to go its own way. The mass eastern support of the Macriani in 260 indicated a similar provincial sentiment – that of a desire for firm local control in the face of a foreign onslaught. In 270 the east would officially break away from Rome which effectively created three separate imperial powers.

In 266, as the emperor Gallienus recovered from his arrow wound, Odaenathus, the ruler of Palmyra, spearheaded his own military campaign against Persia. Driving deep into Mesopotamia he was able to win a stunning victory at Ctesiphon, the Persian capital, an achievement matched only by three Roman emperors before him. These men had the weight of Rome’s military behind them; Odaenathus had his elite Palmyrene cavalry backed by the military forces of the eastern provinces. It was clear that this potentate was running the show in Syria and Mesopotamia.

From the viewpoint of Gallienus, looking outwards from Rome, the Gallic Empire in the west was dealing effectively with German raids. In the east, the Roman proxy Odeanathus was thrashing the Persians on their own territory. Meanwhile, the Danube frontier was quiet. Did this mean peace for Rome at last?