The new engine, deriving from a Merlin type that had been in development for eight years and was powering the increasingly successful Spitfire fighter, arrived with perfect timing. The twelve-cylinder, 60-degree, upright V-shape engine delivered 1,280 horsepower and was to become its standard plant, propelling the aircraft and providing the hydraulic power for the gun turrets and other onboard functions.3 The Merlins drove four three-bladed propellers with a diameter of 13ft, and could get the crew home even if only two were functioning. One engine was enough to keep the bomber airborne, often for long enough to make the difference between capture and safety, death or survival.

There was to be no co-pilot, unlike in the Manchester; a flight engineer would take overall responsibility for the aircraft’s mechanical smooth-running, and act as support pilot should the need arise. The Manchester, for all its faults, had paved the way for a revolutionary new aircraft, the most advanced bomber the world had yet seen.

After the Boscombe Down tests, the design was approved and officially adopted, and its new name formally accepted. On 28 February 1941, a new British legend, the mighty Lancaster bomber, was born. Its fuselage was just over 69ft long, and its wingspan 102ft. It stood a little over 20 feet high, and was powerful enough to take off at an overall maximum weight, depending on variant, of 68,000lb. In the air, it could achieve speeds of up to 282mph and could climb to a height of 21,400ft, at a rate of 720ft per minute, carrying a normal bombload of 14,000lb. Protected by two 0.303-inch Browning Mark II machine guns in the nose and mid-upper turret, and four in the rear turret, the aircraft was designed to carry the largest possible number of bombs the greatest possible distance. It was an airborne bomb carrier, built to the highest specifications, and its business was destruction.

With sleek yet businesslike lines, massive and reassuring to its friends, menacing and deadly to its foes, it was like nothing that had come before. Its fuel capacity of over 2,000 gallons and range of 2,530 miles meant it could take the battle to the very heart of Nazi Germany, and, alongside the young men training to fly her, the Lancaster would have a profound effect on the course of the war.

Thomas Murray had his first crack at flying a Lancaster prototype early in October 1941 and was an immediate and enthusiastic convert. ‘It took off like a startled stallion.’ It was as light as a feather and handled beautifully, almost dancing in the air. Amazingly manoeuvrable, Thomas found it ‘a tonic after the lumbering Manchester’. Very soon, the bomber had acquired its affectionate nickname – the ‘Lanc’. And, as promised, ‘It flew happily on one of its four engines!’

The early-production Lancaster, the B1, took its maiden flight on 31 October 1941. Almost two months later, 44 Squadron, based at Waddington, took delivery of the operational aircraft.

Pip Beck remembered their arrival.

‘On Christmas Eve 1941, 44’s first Lancasters arrived – a magnificent Christmas present for the squadron. It was with intense interest that everyone in Flying Control watched their approach and landing. As the first of the three taxied round the perimeter to the Watch Office, I stared in astonishment at this formidable and beautiful aircraft, cockpit as high as the balcony on which I stood and great spread of wings with four enormous engines. Its lines were sleek and graceful, and yet there was an awesome feeling of power about it. It looked so right after the clumsiness of the Manchester. Their arrival meant a new programme of training for the air and ground crews and there were no operations until the crews had thoroughly familiarised themselves with the Lancasters. There were one or two minor accidents – changing from a twin-engined aircraft to a heavier one with four engines must have presented some difficulties, but the crews took to them rapidly. I heard nothing but praise for the Lancs.’4

There was a special feeling of bonhomie on Christmas Day 1941, as the officers, in time-honoured tradition, donned aprons and served the ‘other ranks’ their Christmas dinner. That winter was a particularly bitter one, but somehow hope had now dared to raise its head. One of Pip Beck’s special friends was a Rhodesian named Cecil, after his country’s founder, Cecil Rhodes. Cecil had come to Britain to work as an RAF aircraft fitter while waiting for a place on a pilots’ course.

‘Cecil had a food parcel from home containing all sorts of good things, including a gorgeous rich fruitcake. He decided to have a party, since discipline was somewhat relaxed for Christmas Day. We fell on the contents of the food parcel with great enjoyment and appreciation, demolishing the rich tinned soup, tinned ham, and sweetcorn served on toast – and, of course, the fruitcake and some chocolate. It was all delicious. The only thing not available was alcohol, but I don’t think we noticed; our spirits were high enough anyway.’

Hope was in the air. Perhaps Christmas 1941 might be the last Christmas at war?

#

Roy Chadwick’s aim had been to keep the design as simple as possible. The Lancaster would be built in a series of sections, each fully finished, so that they could be transported – by road and rail – from any given factory to a different assembly site, close to an airfield. Each Lancaster cost around £50,000 to produce – more than four times as much as a Spitfire5 – but its simplicity made for shorter man-hours, and as 1941 and the first half of 1942 saw the Germans still in the ascendant, the need for a speedy production line was vital.6

‘Keeping it simple’ may have been Roy Chadwick’s watchword, but a great deal went into achieving that, involving thousands of male and female workers, huge factories, vast drawing offices and an efficient, smooth-running timetable. The process wasn’t always perfect, and simple though its essential design was, each Lancaster was made up of around 55,000 separate parts, if you included the rivets and nuts and bolts that held it together. To assemble a Lancaster took 500,000 different manufacturing processes, occupying over 70,000 man-hours. Nevertheless, 7,377 rolled off the production lines during the five years of its manufacture.

Ted Watson visited a factory and was enormously impressed.

‘We could watch the Lancasters being assembled – here were some of the machines I would go to war in. We were even allowed to help on the production line. The process was impressive and it gave confidence that everything was being done correctly! We had a tour round a brand-new Lanc and it looked so smart and pristine, everything was in order, it was clean and calm, and as we looked over each crew position it looked like an impressive workshop – a nice place to work. Of course, I had no idea how that sense of calmness would change when we were working in the Lanc in its proper role!’7

The oval fuselage, aluminium sheets riveted onto a light-alloy skeleton, was designed to be produced in five sections, which not only made transport easier, but meant that if one were damaged, it could be easily replaced. The wings comprised fourteen segments. The central sections were attached by massive spar booms which crossed the fuselage at thigh height. Lancasters were built to dispense bombs, not for comfort. The main spar was just aft of the radio operator’s seat; the rear one about 8ft further back, near a stowage area for parachutes. This crucial assembly, checked and checked again before release from the factory, was vital to the Lancaster’s safety. Tailplanes were also divided into units: the 12ft fins and the 33ft span.

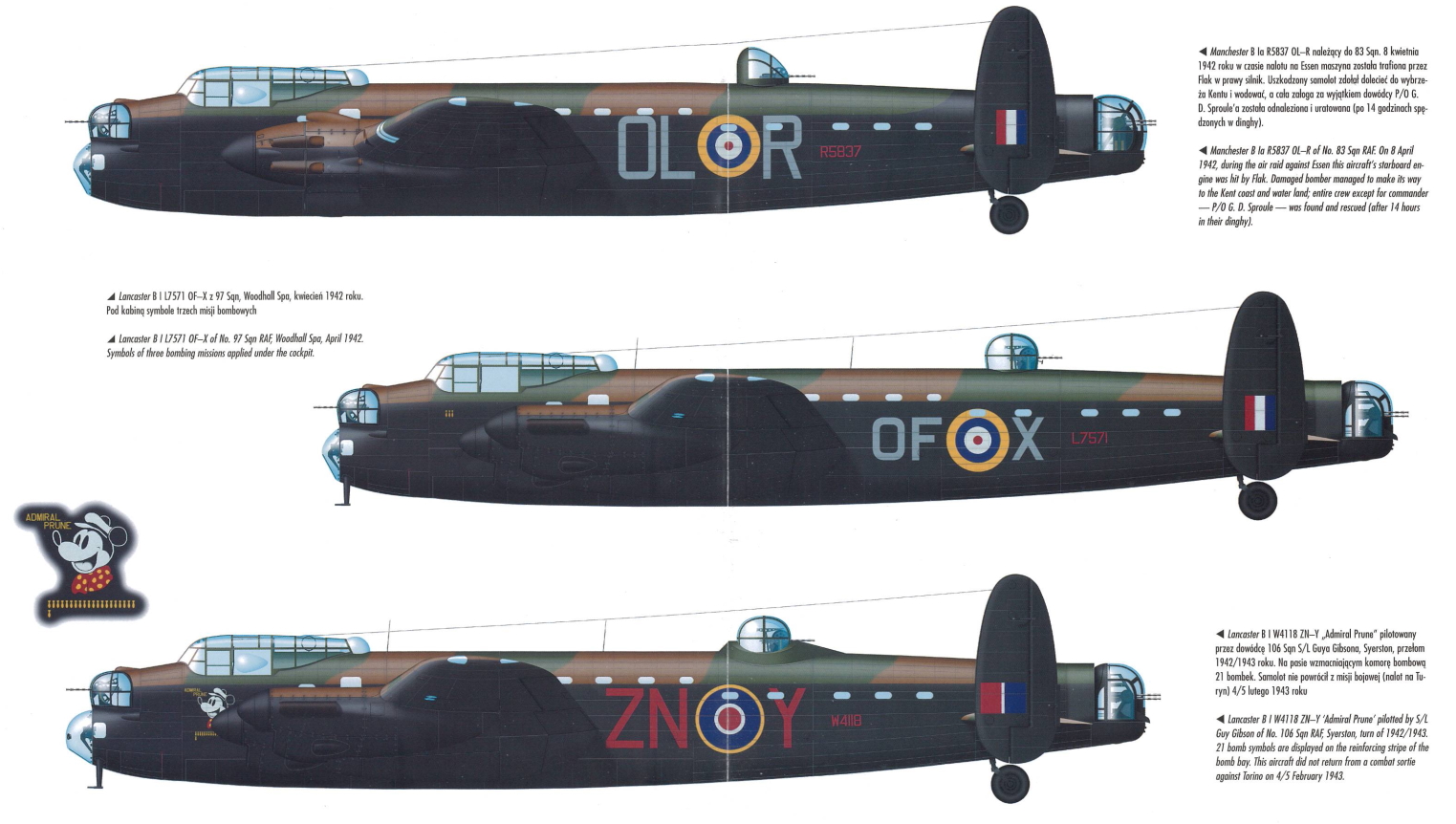

The final touch was the paint; greens and browns on the upper surfaces, matt black underneath. The RAF roundels and the identification numbers and letters were the only bright spots on the entire aircraft. Painting was not an easy job, however. Protective face masks were not yet used, and conditions for workers weren’t easy overall. Machinist Lilian Grundy8 recalled working ten-hour days making bolts for the Lancaster. The conditions were dreadful: ‘It was like going into a dungeon and the noise was horrendous. They had you at the machines all the time.’ At the height of production, shifts were twelve hours long, and the factories worked twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.

Chadderton, Avro’s massive factory near Oldham, complete with an impressive art-deco façade, was responsible for producing over 3,000 Lancasters. It was built in 1938 with the help of a government grant of £1 million. With a floor area of around 750,000 square feet, it was by far the largest aircraft factory of the time, twice the size of any other, and by 1939 it had become Avro’s headquarters. Initially used to build Blenheims, it was given over to Lancaster production from autumn 1941. At night the factory was cavernously dark – the only lights were those used to illuminate the workbenches and the work areas – and the noise was perpetually deafening. Panel-beaters, working without ear shields, had one of the worst jobs. Geoff Bentley, aged fourteen when he started at Chadderton, described it as ‘a hell of a factory’.

‘You could see the Lancasters for miles, fifty of them lined up at a time. Chadderton was a lovely building at the front, with a beautiful big reception and staircase, a bit like a film set. But the factory was so noisy. The riveters would be going all day. I worked for a while in the machine shop, and when those massive presses dropped down, the whole place shuddered.’9

The hard work at the factories soon began to pay off. Thomas Murray’s squadron was stood down to convert to the Lancaster shortly after their last disastrous raid on Essen in a Manchester.

‘At last we had a reliable aircraft with an excellent bombload, rate of climb, and operational ceiling,’ Thomas said. Everyone was more than ready to welcome the new arrival, with new hope and vigour in their hearts. And it wouldn’t be very long before the new aircraft would be getting its first taste of action. Early in 1942, Lancasters were being delivered to Bomber Command squadrons for operational use, replacing outmoded models faster and faster as production increased. Thomas could almost hear the aircrews’ sigh of relief. The effect on morale was palpable.

George VI and Queen Elizabeth paid a visit to the largest factory at Yeadon, Yorkshire, in March 1942. Two recently completed Lancasters were named in their honour. The Times later reported that the King and Queen had both displayed extensive technical knowledge of aviation in their conversations with Chadwick and Dobson – the ‘two Roys’ as they’d become known.

Triumphantly reported by Pathé Gazette, another visit to the Avro factories a month or so later by Squadron Leader John Nettleton and his much-decorated crew from 44 Squadron had an even greater significance for the panel-beaters, pop-riveters, electricians, hydraulic engineers, draughtsmen and everyone else who contributed to the creation of the new bomber. They had recently returned from the Lancaster’s first significant venture, during which Nettleton had been awarded the Victoria Cross, the nation’s highest award for valour, in recognition of his ‘unflinching determination and leadership’.

Kay Mitchell had a newspaper picture of John Nettleton pinned to her workbench instead of the portraits of film stars favoured by the other factory workers. She was overjoyed when the Squadron Leader, looking every bit as pleased and shy as she did, was invited to sign it.