Thomas Murray was born in Dorset at the end of May 1918, four months after the RAF was created from the army’s Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service. Thomas’s father, a former Royal Marines officer, had been involved at its inception, setting up the RAF’s secretarial branch, and rising to the rank of Group Captain. Charles Murray, however, wanted his son to go into his old service – the navy – and although young Thomas grew up in an RAF family, he hadn’t initially felt any great interest in flying himself. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he didn’t make model aircraft or read books about the heroics of the early aviators. But in 1929, when his father was stationed at RAF Halton in Buckinghamshire, all that changed.

‘I remember the moment I knew I was going to be a pilot. I was lying in a field near my school, right next to the airfield. The sun was out and I was watching a Hawker biplane. He performed a spin right over my head! I was totally captivated – as he spiralled down, he was pointing straight at me. I knew, at that moment, I would go into the Air Force. My first flight was at the age of eleven at RAF Halton. The pilot told me what a wonderful privilege it was to be up in the air, at one with the birds. To show this, he found a heron flying along a stream, which he formatted on!’

Thomas underwent a full medical examination at his father’s RAF station and had several hours’ experience under his belt by the time he went up to the RAF College at Cranwell in Lincolnshire. On 5 February 1937 he first went solo – ‘Fifteen glorious minutes of freedom! – Aerobatics and spinning, with some low flying thrown in for good measure!’ He also learned that ‘just flying the aircraft, performing aerobatics well, and formation flying, were not the only skills to be mastered for the new era of RAF pilot. The importance of being able to fly on instruments [flying ‘blind’ in cloud or at night] was becoming a higher priority.’

Thomas joined the RAF at a time when it was expanding and changing. Bomber Command was formed in July 1936, and during the second half of the decade a number of twin-engined bombers were belatedly developed – Blenheims, Hampdens, Whitleys and Wellingtons. But there was a need for heavier, longer-range aircraft that were also capable of carrying a bigger bombload.

The first of these four-engined bombers to enter service was the Short Stirling – notoriously difficult to handle on take-off and landing – in 1940. The Handley Page Halifax followed in November that year. It wasn’t the answer either. Crews quickly nicknamed it the ‘Halibag’. It could carry a 14,500lb payload, but not high enough to avoid enemy interceptors. More powerful engines were installed, but the capacity of its bomb bay couldn’t be increased. The Stirling was withdrawn from Bomber Command service about halfway through the war. The Halifax flew on operations until the end. But something better was needed.

#

The Avro Lancaster was something better. It came into existence almost by accident, and as a result of private determination rather than official encouragement, born of its forerunner, the ‘Manchester’.

A. V. Roe & Company was founded in 1910 in Manchester by Alliott Verdon Roe and his brother Humphrey. In 1911, Alliott hired the volatile but gifted eighteen-year-old Roy Chadwick as his personal assistant. By 1918, Chadwick, a talented draughtsman, had become a designer in his own right. Avro ran into financial difficulties owing to a lack of post-First World War orders, and by 1935, both founding brothers having left the company, it had become a subsidiary of Hawker Siddeley. Chadwick stayed on as designer-in-chief, and paired up with a new managing director, the energetic and equally fiery Roy Dobson, who’d joined in 1914 at the age of twenty-three. By mid-1940, they were working on a new, improved version of their twin-engined bomber, which they’d named after the city of their birth.

At the time of the Manchester’s introduction in November 1940, Thomas Murray was an experienced and seasoned pilot on Hampdens. Thomas flew his first sortie as a second pilot/navigator on 21 December 1939 against the pocket battleship Deutschland, holed up in a Norwegian fjord. ‘We never found it as we had no radio transmitters then, and had to send each other coded letters via a signal lamp, which made things even more complicated. I remember seeing something which looked like a pocket battleship, so we all roared towards it with open bomb doors. It turned out to be a lighthouse on a low-lying island! We must have scared the lighthouse-keeper somewhat.’

Mine-laying and ‘nickelling’ sorties (dropping propaganda leaflets over German cities) followed. At this early stage of the war, ops were usually limited to small numbers of aircraft. The crews were trailblazing for Bomber Command – six-hour night flights, with no autopilot, navigating by compass and stopwatch – and the lessons learned would be invaluable later.

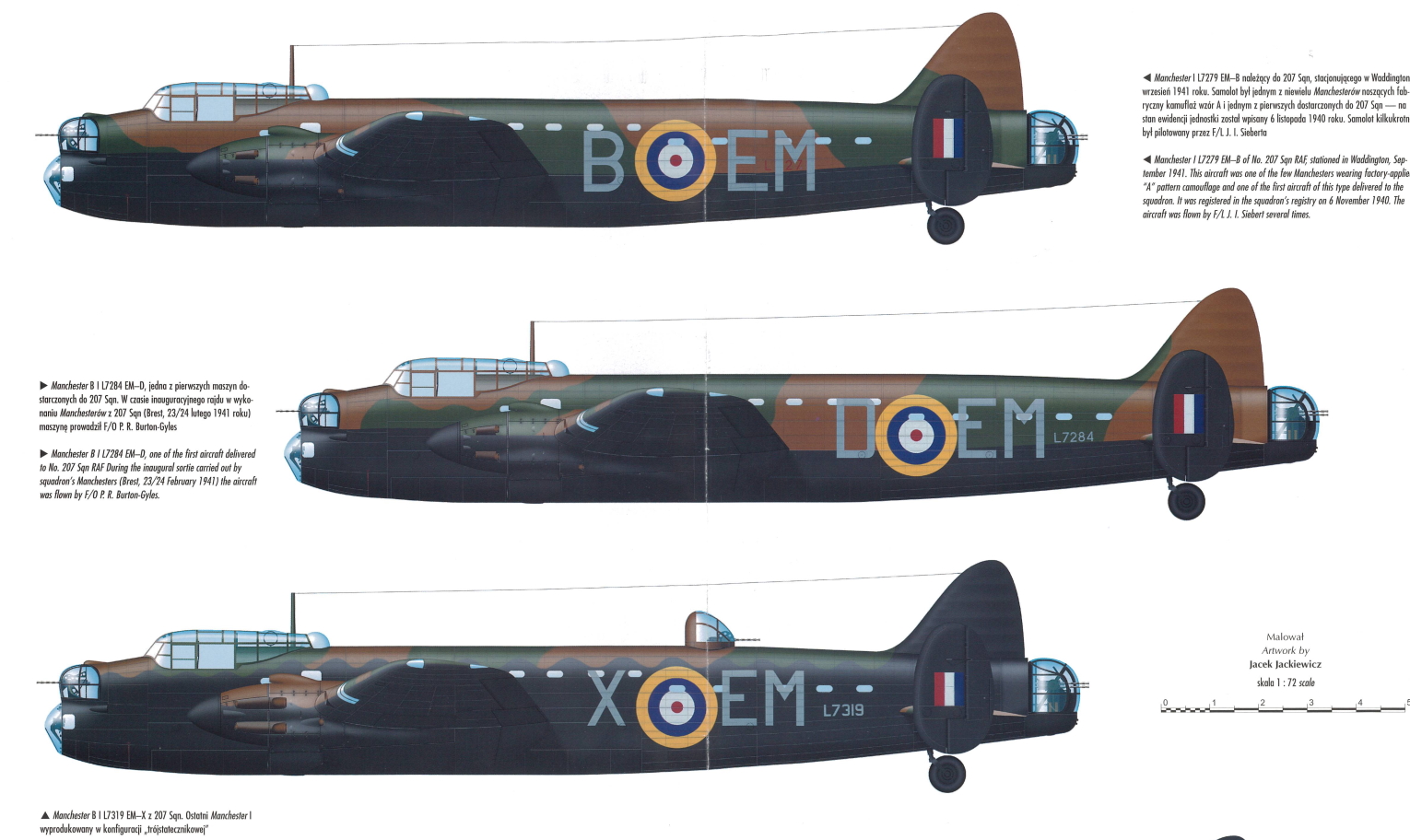

When the first Manchesters were delivered to Thomas’s squadron at RAF Waddington in Lincolnshire, they were seen as a big improvement on the twin-engined aircraft already in service with Bomber Command. With a crew of seven, it was ultimately powered by a pair of Rolls-Royce Vulture IIs, comprising four cylinder blocks from the earlier Peregrine engine, joined by a common crankshaft and mounted on a single crankcase. They delivered around 1,500 horsepower, about 250 less than anticipated, and once in operational service, from early 1941, it quickly became apparent that they weren’t capable of climbing above German anti-aircraft fire. Worse still, the engines were prone to sudden failure, and if one Vulture failed, the remaining engine couldn’t bridge the gap. Improvements were attempted, but with little effect.

Thomas Murray took a Manchester up for the first time on 1 May 1941, and then flew them for a week or so to ‘really get to grips with its handling’, prior to his unit’s conversion from Hampdens. ‘My first impression was that it was a very big aircraft compared with the Hampden. Although it was pleasant to fly, light on the controls, it was colossally underpowered. Our training was on the squadron and not all that methodical – we learned as we went along. These were desperate times, so the aircraft was rushed into service long before it was operationally fit, and while it still had many teething problems. It was light on the ailerons, but unfortunately not at all reliable.’

The authorities had indeed been frantic to get a new, improved bomber into the skies, and turned a blind eye to the Manchester’s failings. Always a man of measured judgement, Thomas Murray became increasingly sceptical. ‘When you were taxiing out with a full bombload, the centre of gravity was slightly wrong, so that the tailwheel would shimmy and be damaged. It meant changing that wheel before you took off. That delay killed a friend of mine. He was at the end of the runway waiting to have his tailwheel changed. As he took off and climbed away, a [marauding German] fighter took him out.’

He had further concerns: ‘The engines themselves were totally unreliable. There were spots where the coolant couldn’t reach so the engines would overheat and start engine fires after a few hours’ running. The hydraulics system, on which the operation of the flaps, undercarriage, bomb doors and turrets depended, was subject to leaking and consequently failure.’

Thomas felt that flying a Manchester demanded the advanced skills of a test pilot, rather than those of a ‘regular’ bomber pilot. Unnervingly, the aircraft were grounded again and again during May 1941 due to recurring engine problems, and when they did fly, ‘I remember my first full bombload take-off. I got the thing airborne and that’s all I could do. It flew along the runway but it looked as if I’d hit the hedge at the end. So I banged the aircraft back down on the ground and fortunately it bounced back into the air, staggering over the hedge. RAF Waddington is on a ridge, and as I went over the edge I managed to get the aircraft’s nose down and increase the speed sufficiently to climb away. We had to fly straight ahead, carrying on for about 5 miles before we dared turn. If you had an engine go on take-off you were a goner.’

A desperate plan was concocted to fly a Manchester continuously around the country until an engine failed, in the hope that the aircraft would nevertheless be able to land safely, the faulty component be identified and sent to Rolls-Royce for examination. On one such flight, Thomas Murray’s own squadron commander headed for Land’s End before turning north towards the Isle of Man. Hardly had he done so than the starboard engine caught fire. He immediately lost height, and ordered the crew to jettison the guns and the dummy bombload to lose weight. He changed course again – for a fighter base near Perranporth in Cornwall, where the strip was too short to land the giant bomber so they had to retract the undercarriage. Skidding along the runway they smashed through two hedges and across a road before a parked lorry finally brought them to a standstill. ‘So Rolls-Royce got their engine and I had to fly down and pick up the crew the following day.’

Thomas Murray flew his last raid in a Manchester over the Krupp’s plant in Essen, in the Ruhr industrial area – ‘Happy Valley’ as the bomber crews called it – with a new navigation system on several of the aircraft. Known as GEE (Ground Electronic Equipment), it received two synchronised pulses transmitted from Britain and determined its position – accurate to within a few hundred yards and effective at up to 350 miles – from the time delay between them. But there were teething troubles. During Thomas’s Krupp’s raid, the GEE-equipped aircraft marking the target with flares were followed by bombers with incendiaries, which obscured the view of the target, causing the next wave to drop their high explosives to little effect.

‘It was one of the worst trips I had to the Ruhr,’ Thomas recalled.

This failure added to the increasing despondency of Manchester pilots. Pip Beck, a nineteen-year-old WAAF radio operator at Waddington, summed up the situation: ‘Anyone who could survive a tour on a Manchester could fly, and was also lucky!’

Further development of Vulture engines was cancelled at the end of 1941 – ‘much to the relief of Rolls-Royce’, as Thomas said – and the Manchesters were withdrawn in mid-1942, after nearly two years’ service, during which they managed 1,269 sorties and dropped 1,826 tons of bombs. Only 209 were built, a disastrous 40 per cent were lost on operations, and a further 25 per cent crashed.

The Ministry of Aircraft Production requested that the Avro plant now be turned over to production of the Halifax, but Avro’s Chadwick and Dobson believed that within their failed twin-engined bomber lay the seeds of a much better, four-engined aircraft. And many of the machine tools used in the production of the Manchester could continue to be used in its production, thus avoiding huge extra costs. So it was that Roy Chadwick persisted in the teeth of initial indifference and even obstruction in official circles, and he and Roy Dobson finally won through. Their partnership – overseeing design and production respectively – was, fortunately for Britain, a brilliant one.

After a series of successful test flights at Ringway (now the site of Manchester International Airport) by test pilot Harry Albert ‘Sam’ Brown, the first four-engined Manchester III BT308 was delivered in late January 1941 to the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment at Boscombe Down in Wiltshire for evaluation. As well as a distinctive twin-finned tailplane, it boasted an extra fin at the rear of the fuselage. A second prototype, fitted with four improved Rolls-Royce Merlin XX engines, took to the skies in mid-May, minus the middle fin. This prototype, DG595, was to be the model for future production, which continued with little variation, except for adaptation for specific tasks and to carry specific bomb-loads, throughout the war.