Shaka’s Zulu Kingdom and the Mfecane Wars, 1817–1828

The Zulu Kingdom and the Mfecane

Until the late eighteenth century the Bantu-speaking mixed farmers south of the Limpopo River lived in small chiefdoms. By the 1830s, when white people began to invade southeastern Africa beyond the Fish River in substantial numbers, however, society throughout the region had been drastically transformed. The nucleus of change lay in northern Nguni country. There, in the country between the mountain escarpment and the Indian Ocean, the Zulu kingdom had incorporated all the northern Nguni chiefdoms. The royal family and its Ntungwa clan constituted a new ruling class. They controlled a standing army of conscripted warriors and exacted tribute from the commoners. Moreover, in a process known as the Mfecane (Zulu) or Difaqane (Sesotho), meaning time of troubles, emigrant bands from modern KwaZulu had created new kingdoms as far north as modern Malawi, Zambia, and Tanzania. The Mfengu, who arrived among the Xhosa and became allied with the Cape Colony, were among the refugees displaced by these events.

This transformation was in essence an internal process within the mixed farming society in southeastern Africa. By the last quarter of the eighteenth century, the relation between the population level and the environment was changing. Previously, the society had been expansive and the scale of political organization had remained small in spite of the tendency of the population to increase, because members of ruling families had frequently split from their chiefdoms with their followers and founded new chiefdoms between or beyond existing settlements. Gradually, however, the population of the region had been increasing to a level where that expansive process was no longer possible. Farmers were reaching the limits of land with arable potential on the verge of the Kalahari Desert in the northwest and in the rugged mountains at the southern end of the highveld. Throughout southeastern Africa, as the possibilities for further expansion diminished, competition for land and water supplies grew more acute.

Changing climatic conditions exacerbated the crisis. Rainfall decreased significantly throughout the region during the first three decades of the nineteenth century, with an exceptionally severe drought between 1800 and 1807, followed by another between 1820 and 1823. The problem was especially serious in the northern Nguni area. There, the terrain is marked by steep hills and deep valleys, which create widely different environments within short distances, and it was necessary for people to move their cattle seasonally from one type of pasture to another. As the land filled up, pastures began to deteriorate through overstocking and people began to interfere with the customary movements of cattle. By the end of the eighteenth century, strong chiefdoms were subduing their neighbors and incorporating them into loosely structured kingdoms. Then came the first great drought of the century, which people remembered as the time when “we were obliged to eat grass.”

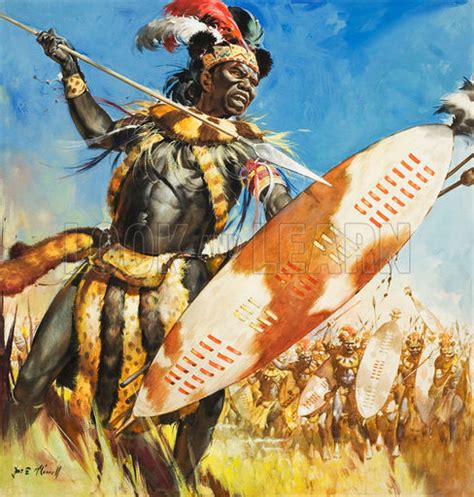

By the 1810s, there were two rival kingdoms in the area: the Ndwandwe kingdom, led by Zwide, and the Mthethwa kingdom, led by Dingiswayo, who created a standing army composed of age regiments. The two kingdoms clashed repeatedly and with unprecedented ferocity. The outcome of the crisis was shaped very largely by Shaka. The eldest son of Senzanga-kona, the chief of the small Zulu chiefdom, Shaka was illegitimate, since his father never married his mother, Nandi. Rejected by his father, Shaka grew up among his mother’s relatives. In Zulu tradition, he was “a tall man, dark, with a large nose, and was ugly,” and “he spoke with an impediment.”

When he was about twenty-two, Shaka joined the army of Dingiswayo, king of the Mthethwa, where he acquired a reputation as a brave warrior and a man of original ideas and became commander of his regiment. When Senzangakona died in about 1816, Dingiswayo helped Shaka succeed to the Zulu chieftaincy over the heads of his numerous legitimate half-brothers. Shaka then equipped the Zulu warriors with short stabbing spears in addition to the traditional long spears and trained them to fight in close combat. A year or two later, the Ndwandwe captured and killed Dingiswayo. The Mthethwa kingdom then disintegrated and Shaka’s Zulu conquered and incorporated its chiefdoms. In 1818, the Zulu defeated the Ndwandwe in a decisive battle at the Mhlatuse River and became the dominant power throughout northern Nguni territory. By the mid-1820s, Shaka’s Zulu had established control over most territory from the Pongola River in the north to beyond the Tugela River in the south and from the mountain escarpment to the sea.

The transformation of the northern Nguni was accentuated by external factors. Some historians believe that foreign trade was crucial in the rise of the Zulu kingdom. Traders from the Portuguese settlement on Delagoa Bay were increasingly active in this period, bartering beads, brass, and other imported commodities for ivory and cattle. Creating competition for control of the trade route, they probably intensified the conflicts and the centralizing process. The available evidence, including the recorded oral traditions of the African informants, however, does not seem to warrant the conclusion that the trade was sufficient to have been the primary cause of the transformation.

One historian has gone so far as to assert that external forces—white slave traders and white colonists and their Coloured allies—bore most of the responsibility for the transformations in southeastern Africa. According to him, the export trade in slaves from Delagoa Bay precipitated the changes among the northern Nguni, and Griquas and Whites from the Cape Colony were the principal disrupters of the African chiefdoms in the modern Transvaal and Orange Free State. The first claim is palpably false: scarcely any slaves were being exported from Delagoa Bay before 1823; subsequently there was a rise in slave exports, but that was a result, not a cause, of the warfare in the area. The second claim draws attention to a previously underestimated factor: Griquas did cause considerable havoc in some parts of the highveld; nevertheless, the main agents of that disruption were Nguni emigrants from modern KwaZulu.

The Zulu kingdom was the end product of radical changes in northern Nguni society that had begun in the late eighteenth century. It was a militarized state, made and maintained by a conscript army of about forty thousand warriors. Instead of the initiation system, which had integrated young men into the discipline of their particular chiefdoms, men were removed from civil society at about the age of puberty and assigned to age regiments, living in barracks scattered throughout the country. During their period of service they were denied contact with women and subjected to intense discipline. They were employed on public works for the state, but their most conspicuous duties were military. In warfare, their standard tactic was to encircle the enemy and then, in close combat, to cause havoc with short stabbing spears. They celebrated a victory by seizing booty, principally in cattle, and, sometimes, by massacring women and children. Survivors were incorporated into the Zulu kingdom under chiefs whose tenure depended on their loyalty.

In earlier times, there had been no standing armies, women and children were seldom killed, and defeated chiefdoms were rarely incorporated. Men, women, and children had lived in their homesteads throughout their lives and had forfeited only a relatively modest amount of their produce to their chiefs. Under Shaka, grain and cattle flowed in larger quantities to the royal residence and the regimental barracks; and, with a high proportion of their mature men absent, women had greater responsibility for rural production and for managing the homestead.

To foster loyalty to the state, Shaka and his councillors drew on the customary Nguni festivals. They assembled the entire army at the royal barracks for the annual first-fruits ceremony and before and after major military expeditions, when they used spectacular displays and magical devices to instill a corporate morale. The traditions of the Zulu royal lineage became the traditions of the kingdom; the Zulu dialect became the language of the kingdom; and every inhabitant, whatever his origins, became a Zulu, owing allegiance to Shaka. Nevertheless, as Carolyn Hamilton, drawing on Zulu evidence, points out, “The process of centralization was far from smooth. . . . . There were . . . great inequalities within the Zulu kingdom, deep-seated divisions and considerable disaffection. . . . [0]utbreaks of rebellion . . . prompted continued coercive responses from the Zulu authorities. These included merciless campaigns and stern sentences for individual rebels. . . . The Zulu authorities fostered this image through carefully managed displays of despotism and brutal justice at the court, using terror as a basis for absolute rule across a huge kingdom.”

During the 1820s, the Zulu kingdom became increasingly predatory. Shaka sent the army on annual campaigns, disrupting local chiefdoms to the north and the south, destroying their food supplies, seizing their cattle. Tensions within the royal family came to a head on September 24, 1828. While the army was away on a campaign to the north, Shaka’s personal servant and two of his half-brothers assassinated him. One of those half-brothers, Dingane, eliminated his rivals and succeeded to the kingship, maintaining Shaka’s domestic and external policies, though he lacked Shaka’s originality and panache.

Meanwhile, militant bands of people who had been driven from their homes by the Ndwandwe, the Mthethwa, and the Zulu created the widespread havoc throughout southeastern Africa that became known as the Mfecane. By the early 1830s, organized community life had virtually ended in some areas—notably, in modern Natal, south of the Zulu kingdom, and in much of the modern Orange Free State between the Vaal and the Caledon river valleys, where the only human beings were small groups of survivors trying to eke out a living on mountaintops or in bush country. Settlements were abandoned, livestock were destroyed, fields ceased to be cultivated, and in several places the landscape was littered with human bones. Demoralized survivors wandered round singly or in small groups, contriving to live on game or veld plants. Some even resorted to cannibalism—the final sign of society’s collapse. A self-proclaimed former cannibal later told a missionary: “Many preferred to die of hunger; but others were deceived by the more intrepid ones, who would say to their friends . . . : here is some rock rabbit meat, recover your strength; however, it was human flesh. Once they had tasted it, they found that it was excellent. . . . Our heart did fret inside us; but we were getting used to that type of life, and the horror we had felt at first was soon replaced by habit.”

By that time, a rival Nguni kingdom controlled much of the central highveld. In about 1821, one of Shaka’s allies, a chief named Mzilikazi, fled over the escarpment to the highveld with a small band of warriors. There, they became known as Ndebele (Nguni) or Matabele (Sotho). Using Zulu military methods, they carved out a state between the Vaal and the Limpopo rivers, conquering several Sotho and Tswana chiefdoms and incorporating many of their people as subordinates, exacting tribute from others, and, like the Zulu, sending impis out to terrorize more distant communities.

Other states were developing on the periphery of the areas dominated by the Zulu and the Ndebele. Several militant bands of refugees from the northern Nguni area, enthused with similar zeal for conquest, struggled to establish themselves in modern Mozambique. The most successful were those led by Soshangane, who created the Gaza kingdom there and drove out others led by Zwangendaba and Nxaba, who eventually carved out new chieftaincies for themselves in parts of modern Malawi, Zambia, and Tanzania. Similarly, a Sotho community known as the Kololo, harrassed by the Ndebele, fled northward from the highveld and eventually founded a kingdom in modern Zambia. In mountainous territory northwest of the Zulu, meanwhile, an Nguni chief named Sobhuza, who had been driven out of land near the Pongola River by Zwide’s Ndwandwe, absorbed several Sotho as well as Nguni communities and created a durable kingdom that became known as Swaziland after Sobhuza’s son and heir, Mswati.

Perhaps the most significant of the new states was Lesotho. Its leader was Moshoeshoe, the senior son of a Sotho village headman, who gathered the survivors of the wars in the Caledon River valley. Besides Sotho, who had belonged to numerous different chiefdoms before the invasions began, they included people who had arrived in the area as members of invading Nguni bands. From headquarters on a flat-topped mesalike mountain named Thaba Bosiu, the Basotho warriers warded off attacks by a series of aggressors, including an Ndebele impi and Griqua raiders.

Lesotho differed fundamentally from the Zulu kingdom. It was the scene of postwar reconstruction on pacific rather than coercive principles. Although Moshoeshoe placed his sons and other relatives over chiefs of other lineages, he never created a standing army, he remained on easy, familiar terms with all and sundry, he encouraged his people to debate public questions freely in public meetings, and he tolerated a great deal of local autonomy. “Peace,” he said, “is like the rain which makes the grass grow, while war is like the wind which dries it up.” With its humane leader and its central position in southern Africa, Lesotho played an important role throughout the next half-century.

In transforming the farming society of southeastern Africa, the Mfecane wrought great suffering. Thousands died violent deaths. Thousands more were uprooted from their homes. Village communities and chiefdoms were eliminated. A century later, Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje, a Motswana, started his novel Mhudi with tragic incidents in the Mfecane. Yet, in Thomas Mokopu Mofolo’s well-known novel Chaka, written in Sesotho and translated into English, German, French, and Italian, and in an epic poem by Mazisi Kunene, the name of Shaka has passed into African literature and the consciousness of modern Africans as a symbol of African heroism and power.

Besides the destruction, the immediate consequences of the wars were twofold. First, thousands of Basotho and Batswana from the highveld, as well as Mfengu and Xhosa from the coastal area, poured into the Cape Colony in search of subsistence, which they were able to obtain by working for white colonists. Second, the wars provided Whites with unprecedented opportunities to expand into the eastern part of southern Africa. In much of the central highveld, the population was sparse throughout the 1830s. The surviving inhabitants, fearing further disruptions, tended to conceal themselves from intruders, which gave white travelers the impression that the area was uninhabited and unclaimed. In fact, however, the rulers of the newly created Zulu, Ndebele, Swazi, and Sotho kingdoms assumed that, jointly, they had dominion over the entire region, though they contested its distribution among themselves. In particular, Dingane and Mzilikazi continued to send impis through the sparsely occupied southern highveld.