Map of Thoroughfare Gap Battlefield core and study areas by the American Battlefield Protection Program

Pope heard nothing regarding command of the joint armies, and assumed Halleck himself would come out from Washington to take the command. Old Brains had no such intention. He—and everyone in the administration—fervently hoped that John Pope, with as much help from the Potomac army as need be, would prevail over the Rebels. A victory by the combined forces under Pope ought to dispose of McClellan without messy political consequences. Heintzelman called it a disgrace. “They want to be rid of McClellan & dont dare to go at it openly. This splendid army has to be broken up to get rid of him. . . .”

Lee fumbled his first advance against Pope’s Rapidan line, and Pope hastily pulled back behind the Rappahannock. His move caught General Meade’s attention: “It appears that Genl. Pope has been obliged to show his back to the enemy & to select a line of retreat.” Lee probed Pope’s new line. On August 22 Jeb Stuart swung around Pope’s western flank and raided his headquarters at Catlett’s Station on the Orange & Alexandria, the Army of Virginia’s supply line. Captured dispatches revealed Pope’s situation and the reinforcements he expected, and confirmed Lee’s appraisal of the situation—that he had scarcely a moment to spare to strike before Pope became too strong to strike at all.

Lee divided his forces to maneuver around Pope’s army and get in his rear—expanding Stuart’s raid on the Orange & Alexandria into a full-fledged offensive. On August 25 Jackson’s 24,000 men slipped away upstream to cross the Rappahannock at an unguarded ford, and turned north, disappearing behind the Bull Run Mountains. Longstreet’s 30,000 stretched their lines to cover Jackson’s old postings and continued skirmishing to occupy the Yankees in front of them.

McClellan’s lieutenants were uniformly pessimistic as the new campaign unfolded. George Meade told his wife the enemy “are evidently determined to break thro Pope and drive us out of Virginia, when they will follow into Maryland & perhaps Penna. I am sorry to say from the manner in which matters have been mismanaged that their chances of success are quite good.” John Reynolds was of like mind: “I am very fearful of the operations. . . . Pope’s Army has not seen or met anything like the force we know left Richmond before we did.” Phil Kearny wrote bitterly, “We have no Generals. McClellan is the failure I have proclaimed him. . . . He will only get us in more follies, more waste of blood, fighting by driblets. He has lost the confidence of all. . . .”

Fitz John Porter was the most public with his complaints. He continued feeding disparaging news and views to editor Marble’s New York World. Disaster was expected: “Military principles violated in case of Pope & putting Burnside where he is. . . . Pope is a fool. McDowell is a rascal and Halleck has brains but not independent.” He echoed McClellan’s wishful thought: “Would that this army was in Washington to rid us of incumbents ruining our country.”

John Pope, for his part, had no illusions about what to expect from the Army of the Potomac. Influence peddler Joseph C. G. Kennedy had passed around for all to see Porter’s July 17 letter with its belittling remarks about Pope. As Pope listened, Phil Kearny denounced the “spirit of McClellanism” infecting officers of the Potomac army and singled out Porter as not to be depended upon. Pope had no illusions about his own army either. He complained that Sigel’s troops must march, “because they will not fight unless they are tired and cannot run.” He insisted to Halleck that Sigel was “perfectly unreliable” and ought to be replaced. Banks’s corps, too, was weak and demoralized and would best be held in the rear. Only McDowell’s corps could be counted on.

On August 25, the day Jackson disappeared behind the Bull Run Mountains, Pope’s Army of Virginia was arrayed defensively behind the Rappahannock. Sigel’s corps held the line to the west and Banks’s to the east, with McDowell’s corps in support at Warrenton. The pieces of the Army of the Potomac were scattered widely. Jesse Reno’s two Ninth Corps divisions had made contact with Banks, but Fitz John Porter’s two Fifth Corps divisions were downstream at Kelly’s Ford. Porter wanted to know who was issuing orders—was it Halleck, Pope, Burnside? “Does General McClellan approve?” he asked plaintively. Reynolds’s Pennsylvania Reserves were attached to McDowell’s corps at Warrenton. Of Heintzelman’s Third Corps, Kearny’s division had reached Warrenton Junction, on the Orange & Alexandria, with Hooker’s division following. Sumner’s Second Corps and Franklin’s Sixth were en route from the Peninsula.

Pope found the command status confusing. He assumed, he told Halleck, “you designed to take command in person.” Until then he did not know what forces were his to use. Was he to “command independently” against the enemy? On the subject of command Halleck was silent. McClellan too questioned Halleck. He asked “whether you still intend to place me in the command indicated in your first letter to me, & orally through Genl Burnside. . . . Please define my position & duties.” Halleck furnished him no satisfaction. On August 26 McClellan took ship for Alexandria and (as he told Ellen), like Mr. Micawber “am waiting for something to turn up.”

When he took command of the Army of Virginia, John Pope found the army’s railroad supply network in the hands of Herman Haupt, the railroad construction engineer and superintendent recruited by Secretary Stanton. Haupt had everything in working order and the trains running on time. He noted the evils he had corrected: “Military interference, neglect to unload and return cars, too many heads, and, as a consequence, conflicting orders.” The only way to run a railroad, said Herman Haupt, was under a single head, on a fixed schedule. Pope reasoned that since the railroad carried army supplies, he would put army quartermasters in charge and dispense with Haupt. In a matter of days the evils returned: Trains stopped running on time, and often just stopped running. Orders came from the field and from Washington and from everywhere in between. Troops lagged in reaching Pope. Supplies lagged reaching the front. Lack of forage crippled the cavalry. The War Department telegraphed Haupt, “Come back immediately; cannot get along without you; not a wheel moving on any of the roads.”

On Haupt’s return, Peter Watson of the War Department advised him, “Be patient as possible with the Generals; some of them will trouble you more than they will the enemy.” For example, Brigadier General Samuel Sturgis. On August 22 Sturgis brought the Orange & Alexandria to a standstill by commandeering four trains to take his division to the front. Haupt found Sturgis well primed with drink and threatening to arrest him, “for disobedience of my orders in failing to transport my command.” Haupt had strict orders from Halleck and Pope that he alone ran the railroads, and soon came a telegram from Halleck promising arrest for Sturgis unless he gave up the trains. Believing in his muddled state that the order came from Pope, Sturgis blurted, “I don’t care for John Pope a pinch of owl dung!” Savoring his construction, he repeated it several times before staff persuaded him that the order was from the general-in-chief. “He says if you interfere with the railroads he will put you in arrest.” “He does, does he?” said Sturgis, drawing himself up. “Well, then, take your damned railroad!”

When Jackson left the Rappahannock on his flank march, he did not escape notice. A Rebel column off to the west, “well closed up and colors flying,” was reported to Banks. He forwarded the sighting to Pope: “It seems to be apparent that the enemy is threatening or moving upon the valley of the Shenandoah via Front Royal, with designs on the Potomac, possibly beyond.” (Confederate interest in the Valley was well known to Nathaniel Banks.) Pope agreed. For Halleck he gauged the column as 20,000 strong and added, “I am induced to believe that this column is only covering the flank of the main body, which is moving toward Front Royal and Thornton’s Gap.”

Pope took comfort in this belief. Seeing the Rebels off to the Valley made them, in effect, someone else’s problem. There should now be time to properly combine the two armies, and with Halleck in command, meet the new threat. Pope did not set forces on the trail of the enemy column, nor did his cavalry track it.

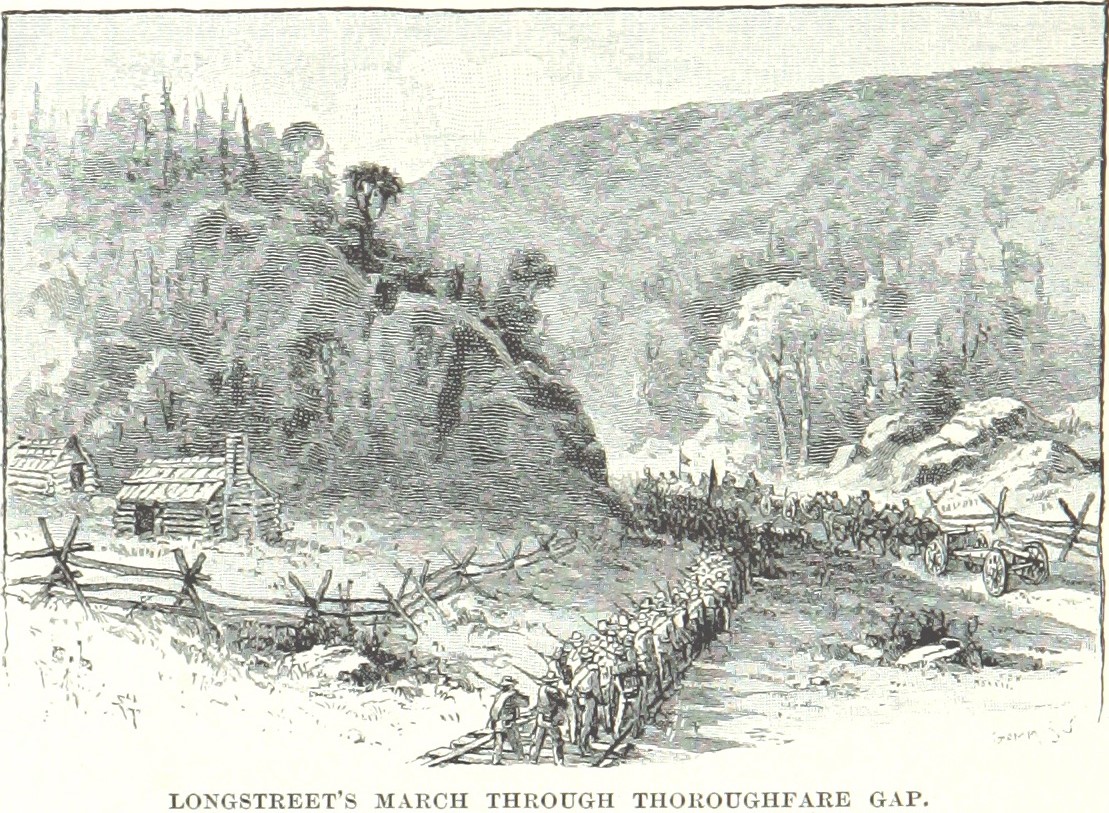

Before dawn on August 26, near the village of Salem midway between the Blue Ridge and the Bull Run mountains, Jackson roused his column from its bivouac. A turn west (which John Pope anticipated) would lead to Manassas Gap in the Blue Ridge and Front Royal and the Shenandoah. A turn east would lead to Thoroughfare Gap in the Bull Run Mountains and the rear of the Army of Virginia. By noon Jackson’s column was passing through Thoroughfare Gap. No Federals barred the way, or sounded the alarm. That afternoon, Lee with Longstreet’s troops left the Rappahannock and set out on the same route Jackson had taken.

At 8:00 p.m. on the 26th Colonel Haupt’s telegrapher at Manassas Junction reported, “No. 6 train, engine Secretary, was fired into at Bristoe by a party of cavalry—some say 500 strong. . . .” Haupt passed the news to Halleck. Jackson’s vanguard, it developed, had cut the Orange & Alexandria at Bristoe Station, then five miles up the line captured Manassas Junction, the Army of Virginia’s principal supply depot. By day’s end General Pope was aware that his communications were cut, and by more than a party of cavalry. It was belatedly reported to him that a substantial body of Confederate infantry, artillery, and cavalry had traversed Thoroughfare Gap and just then was squarely between his army and Washington.

Once over his surprise, Pope saw opportunity here. McDowell made the case: “If the enemy are playing their game on us and we can keep down the panic which their appearance is likely to create in Washington, it seems to me the advantage of position must all be on our side.” This flanking column of Jackson’s may have cut communications with the capital, but Pope held the central position in the area of maneuver. If they moved quickly, the Federals might fall on Jackson from two, possibly three directions.

Pope’s orders for August 27 had his forces abandon the Rappahannock line and pivot 180 degrees. On the left, McDowell with his own corps, Sigel’s corps, and John Reynolds’s division would advance from Warrenton northeasterly to Gainesville, on the road Jackson had followed to Manassas Junction. Jesse Reno’s two Ninth Corps divisions, with the Third Corps’ Phil Kearny, were to march north from the Orange & Alexandria to support McDowell. Banks’s corps and Porter’s two Fifth Corps divisions would move in support from Warrenton Junction. Joe Hooker’s division, Third Corps, was directed up the railroad toward those Rebels who might still be at Bristoe Station. The total force came to some 70,000 men.

These Potomac army units brought a sense of relief to the beleaguered Army of Virginia. David Strother of Pope’s staff was curious to meet the Peninsula generals so praised in the papers. “Hooker is a fine-looking man, tall, florid, and beardless,” he noted in his diary. “Heintzelman is a knotty, hard-looking old customer with a grizzled beard and shambling one-sided gait. Evidently a man of energy and reliability.” Another of Pope’s officers, Carl Schurz, described meeting the famous Phil Kearny: “A strikingly fine, soldierly figure, one-armed, thin face, pointed beard, fiery eyes,” wearing a jauntily tipped cap that gave him the look of a French legionnaire.

Irvin McDowell saw here the chance to retrieve his fortunes. Washington Roebling of the staff wrote in his journal, “All day long McDowell was in an excited but exhilarated state of mind, very hopeful and confident, but savage as a meat axe, as one poor Wisconsin private can testify, his head being half knocked off because he straggled.” Francophile McDowell was heard to mutter that tomorrow would see “une grande bataille, une grande bataille, une grande bataille. . . .”

Pope designed his orders to press Jackson from the west and south with every man then under his control. Advancing on Jackson from the east, by Halleck’s order (and Pope’s request), was to be Franklin’s Sixth Corps of McClellan’s army, just then at Alexandria. Colonel Haupt, intent on getting his railroad running, pitched in on his own account. He collected an idle brigade of Franklin’s, under George W. Taylor, and two Ohio regiments of Jacob Cox’s division, just arrived from western Virginia, and sent them with a work train down the Orange & Alexandria to see how far they could get.

On the map this convergence of Union forces looked most promising. However, these forces were widely scattered to start with, and under a varied lot of generals from a varied range of commands. To further complicate matters, the Potomac army units were arriving from the Peninsula short of cavalry, artillery, transport, ammunition, and provisions. Most columns marched without cavalry in the lead. “Every minute came a new order,” Alpheus Williams wrote; “now to march east and now to march west, night and day.”

While most Federals spent August 27 marching, three clashes with Stonewall Jackson marked the day. When word reached Washington of the affair at Manassas Junction, the 2nd New York Heavy Artillery was sent out to put things right. At daybreak the “heavies,” acting as riflemen in this their first venture outside the capital, stumbled into Jackson’s men and met a storm of fire. Colonel Gustav Waagner admitted his men “became a little scattered, but nevertheless the retreat was conducted in tolerably good order.” Soon the trains with Colonel Haupt’s ad hoc expedition reached the scene. George Taylor’s New Jersey brigade (Phil Kearny’s ex-command) deployed against the supposed party of raiders and was startled by the same deadly fire that drove off the heavies. Taylor ordered a withdrawal. In the Jerseymen’s scramble to get back across the railroad bridge over Bull Run, Taylor fell mortally wounded.

The third clash with Jackson originated on Pope’s orders. Sam Heintzelman had his Third Corps at Warrenton Junction, and despite the delays and headaches, he was encouraged. “The rebels have lost the opportunity to defeat Pope,” he told his diary. “Our reinforcements are coming in position too rapidly”—just a day or two more. But he was troubled by a command void: “No one appeared to know what to do, or rather to think it necessary to do anything.” In Pope’s realignment, the Third Corps became the right wing. Phil Kearny and Joe Hooker were two of the best fighting generals in the Potomac army, yet Pope elected to deliver only a half swing. He split the Third Corps, assigning Kearny to the center and Hooker to advance alone up the railroad.

Hooker scouted the Rebel position at Bristoe Station, then swiftly deployed his three brigades to engage Jackson’s lieutenant Dick Ewell. Under Cuvier Grover, Joseph B. Carr, and Nelson Taylor (filling in for Dan Sickles, busy politicking in New York), the Yankee brigades fought their way around the Confederates’ flank. At sunset Ewell withdrew to Manassas. Limited ammunition prevented any pursuit. Absent Kearny’s division, Hooker’s fight at Bristoe Station fell short of its promise.

Herman Haupt’s estimate of 20,000 Rebels holding Manassas Junction and blocking Pope’s supply line came as sobering news for General Halleck—and for General McClellan. From Alexandria he wrote his wife on the morning of the 27th, “Our affairs here now much tangled up & I opine that in a day or two your old husband will be called upon to unsnarl them.” Only Franklin’s Sixth Corps and Sumner’s Second, some 25,000 men, remained under McClellan’s command, and Halleck was calling on him to send Franklin’s corps to Pope “as soon as possible.”

It soon developed that General McClellan doing anything “as soon as possible” was impossible. With Jackson cutting Pope’s telegraph link to Washington, reports from the front originated with Fitz John Porter, who retained a roundabout link with Burnside at Falmouth. Announcing battle was imminent, Porter waxed contemptuous: “Would that I were out of this; I don’t like the concern.” “The strategy is magnificent, and tactics in the inverse proportion.” “I find a common feeling of dissatisfaction and distrust in the ability of any one here.” “I wish myself away from it, with all our old Army of the Potomac, and so do our companions.” Burnside warned Porter about his imprudent language but was obliged to forward these dispatches to headquarters. From reading them McClellan framed his own distinctive view of events.

His first thought was to hold Franklin’s corps at Alexandria until it could be massed with Sumner’s arriving corps. Halleck said that Franklin “should move out by forced marches.” McClellan said the Sixth Corps was not yet fully equipped; Franklin could not “effect any useful purpose in front.” The real threat was not to Pope but to Washington itself. “I think our policy now is to make these works perfectly safe, & mobilize a couple of Corps as soon as possible, but not to advance them until they can have their Artillery & Cavalry.” He had no time for details, replied the harried general-in-chief. “You will therefore, as ranking general in the field, direct as you deem best.” So it happened that no marching orders were issued to the Sixth Corps on August 27 . . . and no marching orders were issued for August 28, either. Franklin told his wife, “We are still in status quo, and I hardly think we will move for a while yet.”

David Strother closed his August 27 diary entry with the prediction “Tomorrow there will be a grand denouement.” That was Pope’s prediction as well. His orders for the 28th breathed fire and purpose. He told Phil Kearny, “At the very earliest blush of dawn push forward with your command with all speed to this place . . . and we shall bag the whole crowd.” He repeated the image to McDowell, and added, “Be expeditious, and the day is our own.” His orders directed all his forces to or toward Manassas Junction.

General Pope’s exploits in the Western theater had involved static, fortified enemy positions—Island No. 10 in the Mississippi, New Madrid in Missouri, Corinth in Mississippi—and that experience perhaps fed his confidence that the next day, August 28, he would find Stonewall Jackson waiting at Manassas to receive his attack. Even the sight during the night of a giant conflagration at his supply base, easily visible to every Yankee soldier within 10 miles, did not persuade him that perhaps his quarry had finished his work there and was moving on.

As was indeed the case. Through the night, the Confederates slipped out of burning Manassas north by west, by various routes, to take up a position on the edge of the battlefield of First Bull Run (as henceforth it would be numbered) just north of the hamlet of Groveton on the Warrenton Turnpike. Jackson and Lee, in communication by courier, were confident now of reuniting the two wings of the Army of Northern Virginia. Their task was to engage Pope in battle before the arrival of any more of McClellan’s army made the odds too long.

Thanks to what cavalry was still functioning, McDowell was aware of Longstreet’s approach to Thoroughfare Gap. Commanding almost half the combined Federal forces, he initially thought to post four divisions to defend the Gap. But none of Pope’s orders for August 28 mentioned Longstreet or any threat he might pose, and his orders were explicit: McDowell to “march rapidly on Manassas Junction with your whole force.” McDowell decided to not quite obey. He directed James Ricketts’s division of his corps to Haymarket, three miles east of Thoroughfare Gap. Ricketts was to keep close watch to the west, and should an enemy force appear, “march to resist it.” While less than even a half measure, this seemed to McDowell better than doing nothing.

Then, on August 28, nothing went according to plan. All morning Pope “nipped into delinquents of all grades,” wrote Colonel Strother. One delinquent was Fitz John Porter, whose delayed start earned him a black mark in Pope’s book. Another was Franz Sigel, whose slow assembly held up those behind him. Sigel then marched off in the wrong direction. This proved merely an irritant, for there was no Stonewall Jackson to fight. Kearny reached Manassas Junction about noon to find Pope’s supply base one square mile of ruins. “Long trains of cars lately loaded with stores of all kinds were consumed as they stood on the track, smoking and smoldering, only the iron work remaining entire,” Strother wrote. “The whole plain as far as the eye could reach was covered with boxes, barrels, military equipment, cooking utensils, bread, meat, and beans lying in the wildest confusion. The spoilers had evidently had a good time and feasted themselves while they destroyed.”

Interrogation of stragglers had Jackson headed to Centreville. Pope ordered McDowell to redirect his pursuit to Centreville. Pope’s courier crossed one from McDowell carrying a cavalry report of Longstreet at Thoroughfare Gap. This caused Pope to think of changing his target to Longstreet. Defeating him or driving him away would isolate Jackson and ensure his defeat as well. New orders, sent at 2:00 p.m., went to McDowell: Halt the march to Centreville and instead assemble at Gainesville, on the Warrenton Pike east of the Gap. Heintzelman’s and Reno’s corps would also be directed there. That should be force enough to crush Longstreet.

But just then came fresh evidence regarding Jackson, as noted by Heintzelman: The enemy at Centreville “are reported 30,000.” By this point John Pope was being swayed by whatever latest word reached him. He abandoned the short-lived movement against Longstreet and reverted to pursuing Jackson—and reverted as well to his conviction that (as he later testified) “we were sufficiently in advance of Longstreet . . . to be able to crush Jackson completely before Longstreet by any possibility could have reached the scene of action.” At 4:15 p.m. yet another set of orders went to McDowell: “Please march your command directly upon Centreville from where you are.” Also redirected to Centreville were Sigel, Kearny, Reno, and Hooker. Figuratively throwing up his hands, McDowell set off to find Pope for a face-to-face meeting.

“A dozen orders were given & countermanded the same day and the troops subjected to a lot of useless marching,” complained staff man Washington Roebling. Meanwhile, James Ricketts found himself confronting the vanguard of Longstreet’s wing of Lee’s army. Ricketts’s orders were to “march to resist,” so while the rest of McDowell’s troops pushed east to seek out Jackson, he pushed west with his division to contest the advance of 30,000 Confederates.

In the forty hours since they learned of Jackson’s raid on Manassas, Pope and his confidant McDowell had neither met nor exchanged dispatches to craft joint operations for the swiftly evolving campaign. On August 28, except for his brief flurry of interest in Longstreet, Pope simply ignored that half of the Rebel army and devoted all his energies to cornering Jackson. McDowell had serious concerns about Longstreet’s threat, but failed to communicate them to Pope. Had he exercised command discretion and twelve hours earlier attempted to block the narrow defile of Thoroughfare Gap, in the manner of the Spartans at Thermopylae, he might have created a problem for Lee. As it was, Ricketts engaged in a forlorn hope.