San Martín was a fine example of Portuguese shipbuilding skills. Note the bonaventure mast, set well in-board and not requiring the precarious stern-boom fitted on Henry Grace à Dieu.

This painting by Charles Dixon (1872–1934) of the action between San Martín and Ark Royal in the Channel is indicative of how the English ships were smaller and handier than the massive Spanish vessels. Both were the flagships of the combating fleets.

Though built as a Portuguese man of war, San Martín achieved fame as a ‘Spanish galleon’, the victorious flagship in the Battle of Terceiro (1582) against France, but less fortunate as flagship of the Great Armada sent against England in 1588.

In 1580 Portugal was annexed to Spain and its naval strength was combined with Spain’s, including some fine ships of the galleon type. The Portuguese naval tradition was a strong one and the clean, simple lines of San Martín, with its two gun decks, exemplify the best warship design of 1570–80, and make an interesting comparison with those of ‘Great Harry’, which was still something of a floating castle rather than a fighting ship.

Evidently San Martín was better than anything Spain currently had, as it was very quickly given the status of capitana general, or flagship. On 15 July 1582 it led the fleet at the Battle of Terceiro, off the Azores, when the Spanish, commanded by the Marquis of Santa Cruz, defeated a 60-ship French fleet. This was the first fleet action between ships of the galleon type, and 10 French ships were sunk without claiming a single Spanish one.

Spanish Armada

Carrying so many guns, San Martín was purely a fighting ship, and had no further active deployment until May 1588, when a huge fleet was assembled for the invasion of England. Again San Martín was the headquarters ship, carrying the Duke of Medina Sidonia and his staff. The story of the Armada’s failure, against a combination of English tenacity and ill weather, is well-known. In the context of the history of the battleship, San Martín provides a lesson which may not have been so apparent at the time. The Spanish galleons were warships intended to engage in close combat and their guns were not effective at other than close range. Although generally smaller, the English ships had guns of greater range and could bombard the Spanish from a distance without risking being boarded by enemy soldiers.

San Martín, in an hour-long duel with the Ark Royal on 1 August and another with Triumph on the 4th, was holed beneath the waterline and was rescued by the intervention of other ships. After a few days partial respite, battle was joined again on the French side of the English Channel from 8 August, off Gravelines, and San Martín fought a fierce rearguard action against numerous English ships, including Sir Francis Drake’s Revenge, while the rest of the fleet moved northwards along the Dutch coast. This was a close action, but not so close that the galleons could grapple their fast-moving opponents, board them and force them to surrender. By 9 August it was obvious that the Armada was not able to command the sea and bring its invasion force to land. Its return to Spain round the stormy coasts of Scotland and Ireland left many ships wrecked. San Martín was one of the 67 which got home, out of over 130 ships, reaching Santander on 23 September.

The lesson was that the quality of guns and gunnery was important: not merely an extra but potentially decisive in a battle on the open sea. This was not necessarily palatable to seamen brought up in the old grappling and boarding tradition. The technology of cannon casting, and of the missiles fired – solid iron balls – was to change only slowly and gradually, and two hundred years later ships armed with far more and heavier guns would still seek to get alongside an opponent and storm its decks with armed men. But the value of cannon had been clearly shown.

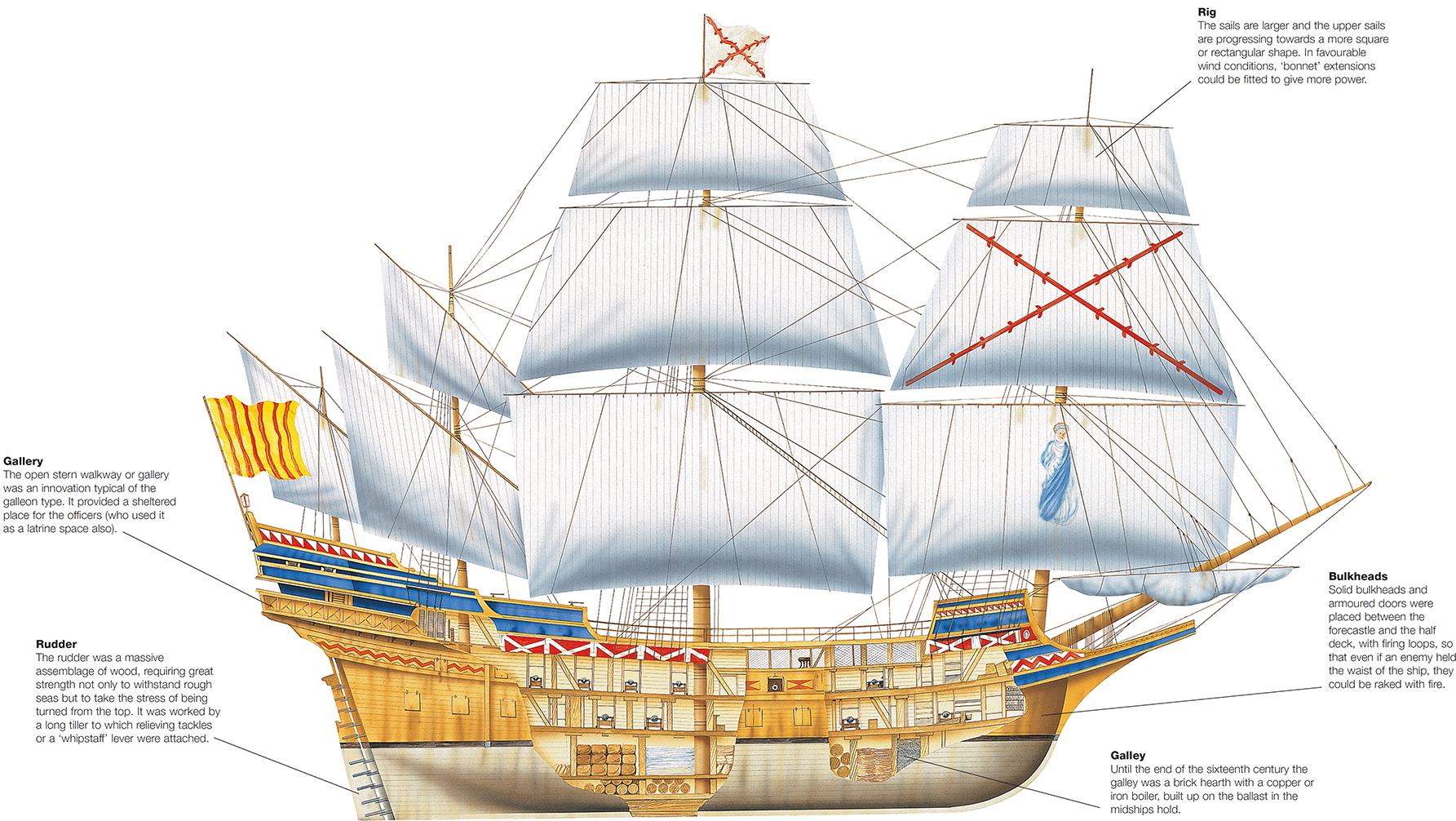

The galleon

The galleon was a large ship, typified by a narrow length-to-beam ratio, a lower freeboard (deck height above waterline) than was usual and a square stern. It was not built as high at forecastle and sterncastle as preceding ships, and had three, occasionally four, masts. The deck extended in a pointed beak over the bow. The aim was to produce a fighting platform that was faster and easier to work than the high-built warships typical before 1575. Gun-decks were built-in and usually held the latest models of cannon. The English Revenge (1577) carried 2 demi-cannon, 4 cannon-periers, 10 culverins, 6 demi-culverins and 10 sakers, apart from smaller guns. All the major seafaring countries built galleons: England, France, Holland, Spain, all with similar features but varying in size, type of armament and even rig: the term (first used in English around 1529) is not a precise one in ship-design.

Size, strength and manoeuvrability

Ark Royal, the flagship of the English Admiral, Lord Howard, was of 629 tonnes (694 tons) burthen compared to San Martín’s 907 tonnes (1000 tons), but carried four masts and 38 guns, including four 60-pounders, four 30-pounders and twelve 18-pounders. Like most of the other English ships, it was more manoeuvrable than the bigger Spanish vessels, but despite superior gunnery, the English fleet did not have the power to destroy the massive galleons. Size and strength counted for something, too. After September 1588, San Martín must have been in poor condition, badly in need of repair and refitting. The war was not over, and the Spanish had to regroup and reform their naval forces against attack from England, France and the Netherlands. All effective craft must have been kept in action, or quickly restored, but San Martín’s subsequent fate is unknown.

Specification

Dimensions:

Length 37.3m (122ft 3in); Beam 9.3m (30ft 9in) Displacement 907 tonnes (1000 tons)

Armament: 48 heavy guns, plus light pieces

Rig: 3 masts, square rig (possible 4th stern mast)

Complement: 350 seamen and gunners; 302 arquebusiers and musketeers