Infantry bunker of the Mareth Line

A line from the Book of Job was among Bernard Law Montgomery favorites: “Yet man is born unto trouble, as the sparks fly upward.” He was a master of organization and training, of the set battle, of the theatrics of command. “Kill Germans, even padres—one per week and two on Sundays,” he told his soldiers. Not a man among the 200,000 in Eighth Army doubted that he was their leader, or that he would be stingy in spending their lives. That was something. A majority of his forty-three infantry battalions came from Commonwealth or allied armies, and he had enough political moxie to avoid prodigality with other nations’ troops. After taking command in Egypt in mid-August 1942 under Alexander’s indulgent supervision, Montgomery had whipped Rommel first at Alam Halfa, then a second, decisive time at El Alamein. That British attack on October 23, with more than a thousand tanks, cracked the much weaker Axis defenders across a forty-mile front. “The sheer weight of British resources made up for all blunders,” one account noted. Twelve days later, Rommel was in the full retreat that had led to southern Tunisia. Until Alamein, the British Army had been mostly winless; his victory in Egypt gave new life to Churchill’s government and to empire, at a cost of 13,560 British casualties but with more than twice as many exacted from his enemies. Church bells had pealed in Britain for the first time in three years. Fan letters arrived at Montgomery’s bivouac by the thousands, including some marriage proposals, and soldiers rushed to glimpse his passing car as if he were a film star, which now he was. “We all trust him to win,” one brigadier said. As a redeeming virtue, that too was something.

And yet. Sparks flew up around Montgomery. He was puerile, petty, and egocentric, bereft of irony, humility, and a sense of proportion. It would not suffice for him to succeed; others must fail. “If he admitted to an error, it was always minor, and served, like a touch of black in a color scheme, to throw up his general infallibility,” the historian Correlli Barnett would write after the war. Acknowledging the “chaos of his temperament,” his biographer Ronald Lewin described

a kindliness and intermittent humanity marred by ruthlessness, intolerance, and sheer lack of empathy; a marvelous capacity for ignoring the inessential, combined with a purblind insensitivity about the obvious; a deep but unsophisticated Christianity; a panache, a burning ambition, above all an individuality—such were the gifts which both good and bad fairies brought to Montgomery’s cradle.

He disdained the French—“quite useless except to guard aerodromes”—and especially the Americans, to whom he would be miserably yoked for the duration of the war. Montgomery dismissed Eisenhower, whom he had met in Britain just long enough to rebuke for lighting a cigarette, in four words: “Good chap, no soldier!” After their second meeting, soon to occur near Mareth, he would embroider his assessment of the commander-in-chief in a letter to Brooke: “He knows nothing whatever about how to make war or to fight battles; he should be kept right away from all that business if we want to win this war.” Before ever seeing the U.S. Army, he proclaimed that “the real trouble with the Americans is that the soldiers won’t fight. They haven’t got the light of battle in their eyes.”

Montgomery was perhaps most controversial among his own countrymen. He deemed Anderson “quite unfit to command an army.” First Army as a whole was worthless. “The party in Tunisia is a complete dog’s-breakfast,” he declared, “and there is an absence of good chaps over there.” He quipped that he intended to “drive the Germans and the First Army back into the sea.” A senior British general considered him “a thoroughly disloyal subordinate.”

Swaggering into Tunisia, Montgomery and his army were also thoroughly overconfident. He envisioned a grand sweep to Tunis, with more laurels and church bells awaiting him. “We will roll up the whole show from the south,” he told Alexander. Churchill tartly noted: “Indomitable in retreat, invincible in advance, insufferable in victory.” Yet the army lumbered like “a dray horse on a polo field,” in Correlli Barnett’s phrase, despite an enthusiasm for the amphetamine benzedrine, which was issued in tens of thousands of tablets “to all Eighth Army personnel” on Montgomery’s order.

Contrary to the Desert Victory mythology, pursuit after Alamein was hardly “relentless.” Rommel had escaped with the core of his army despite a fifteenfold British advantage in tanks, an artillery superiority of twelve to one, and an intimate knowledge of Axis weakness thanks to Ultra and other intelligence. Eighth Army had hugged the ancient Pirate Coast across Libya much closer than it hugged the retreating Axis. That lollygagging had allowed Rommel time to drub the Americans at Kasserine, return to Médenine for a drubbing of his own, then slip away again. “Once Monty had his reputation,” charged the British air marshal Arthur Coningham, “he would never risk it again.”

Now another chance to bag the enemy army obtained, thanks to a stand-or-die order from the Axis high command.

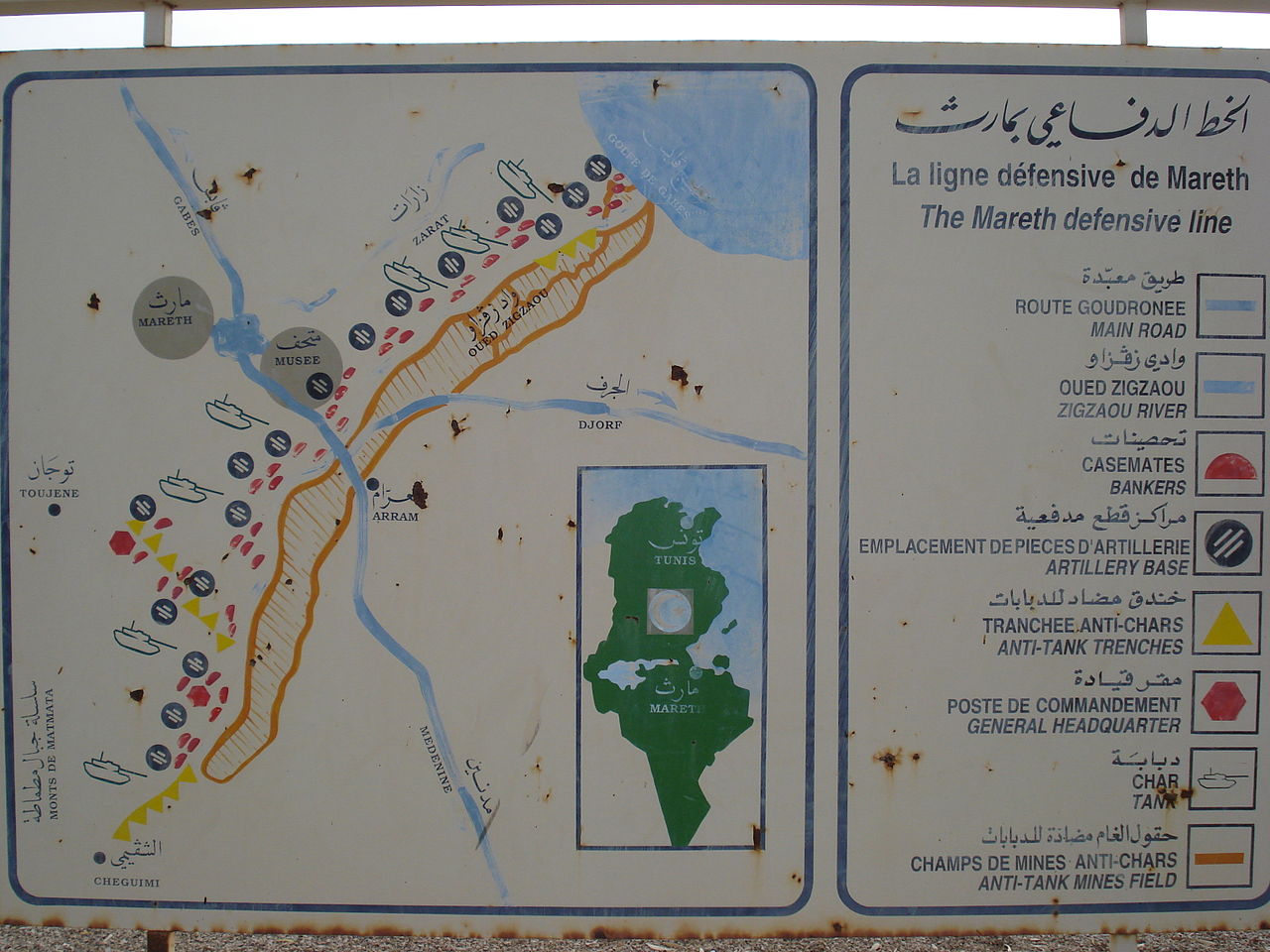

This time the last ditch was to be dug at Mareth, a line of fortifications stretching twenty-two miles between the Mediterranean and the rugged Matmata Hills in the south. For centuries, the narrow coastal gap had been the main portal into southern Tunisia for trans-Saharan caravans carrying slaves and ivory. It was said that traveling merchants seized by Berber highwaymen were forced to drink vats of hot water to flush out any gold they had swallowed.

Although Hitler had vacillated before ordering Mareth held, Kesselring—ignoring Rommel’s skepticism—considered the position a suitable place to begin converting Tunisia into “one vast fortress.” A retreat farther up the Tunisian coast, toward Gabès or Sfax, might allow the merger of Alexander’s two armies; it would also shorten Allied bombing runs to Tunis and Bizerte. Under orders issued by Comando Supremo on March 17, Mareth was “to be defended to the last.” With Rommel gone to Europe, Arnim would command the Axis army group that comprised his own Fifth Panzer Army in the north and Panzer Army Africa, renamed First Italian Army, in the south. The latter included remnants of the Afrika Korps among its 50,000 Germans and 35,000 Italians, and was commanded by General Giovanni Messe, who for the past two years had led the Italian expeditionary corps in Russia.

Built by the French in the 1930s to thwart Italian aggression from the east, the Mareth Line by an odd turn was now garrisoned by twenty-two Italian battalions backed and flanked—“corseted”—by ten German infantry battalions and the 15th Panzer Division with thirty-two functioning tanks. Wadis were scarped into antitank ditches—more than a hundred feet wide and twenty feet deep in places. Thick plaits of barbed wire screened the front, which was four miles deep and seeded with 170,000 mines. Twenty-five decrepit French blockhouses marked the line, some with concrete walls ten feet thick. The Axis flank to the west beyond the hills was protected by chotts—desert salt lakes—and was marked on French maps as terrain chaotique.

These engineering nuances were known to the Allies, of course. Anglo-American intelligence possessed not only the Mareth blueprints but also the former French commander, who, Beetle Smith reported, was indulged in Algiers with six aides—“one for himself and five for his wife. The five were always borrowing ham and bacon and sugar for Madame.” On March 12, Alexander offered his assessment of enemy intentions at Mareth in a lilting if ambiguous message drawn from the twelfth chapter of Revelation: “The devil is come down unto you, having great wrath, because he knoweth that he hath but a short time.”

Mareth Fortifcations

The Mareth Line was a system of fortifications built by France in southern Tunisia in the late 1930s. The line was intended to protect Tunisia against an Italian invasion from its colony in Libya. The line occupied a point where the routes into Tunisia from the south converged, leading toward Mareth, with the Mediterranean Sea to the east and mountains and a sand sea to the west.

The line ran along the north side of Wadi Zigzaou for about 50 km (31 mi) south-westwards from the Gulf of Gabès to Cheguimi and the Djebel (mountain) Matmata on the Dahar plateau between the Grand Erg Oriental (Great Eastern Sand Sea) and the Matmata hills. The Tebaga Gap, between the Mareth line and the Great Eastern Sand Sea, a potential route by which an invader could outflank the Mareth line, was not surveyed until 1938.

After the French Armistice of 22 June 1940, the Mareth Line was demilitarised under the supervision of an Italo-German commission. Tunisia was occupied by Axis forces after Operation Torch in 1942 and the line was refurbished and extended by Axis engineers into a defensive position by building more defences between the line and Wadi Zeuss 3.5 mi (5.6 km) to the south but French-built anti-tank gun positions were too small for Axis anti-tank guns which had to be sited elsewhere.

The Mareth Line consisted of casemates surrounded by barbed wire and built for all-round defence in the main and reserve lines, the obstacles being doubled on the fronts and sides. The strongpoints in the main line included flanking machine-gun casemates and anti-tank gun positions; in the reserve line artillery emplacements provided covering fire in the gaps between the strongpoints in the main line. Some of the flanking casemates for machine-guns covering the gaps were connected by galleries; strongpoints on the plain and in hills had anti-tank positions. An anti-tank obstacle of vertical rails was built along the front of the line and the sides of Wadi Zigzaou were steepened. Eight artillery casemates, forty infantry casemates or blockhouses and fifteen command posts were built. The eastern sector had twelve strongpoints in the main line and eleven in the reserve line. The western sector had eleven strongpoints in the main line and seven in the reserve line.

In the Matmata hills, Ksar el Hallouf covered an anti-tank ditch which continued the position beyond the main line which ended on the foothills. An infantry position was dug into the Matmata hills at Ksar-el-Hallouf and in the Dahar beyond, a strongpoint at Bir Soltane had two 75 mm turrets, removed from Char 2C tanks built in 1918. At Ben Gardane an advanced position was built consisting of a square redoubt inside an anti-tank ditch with casemates on the flanks and concrete infantry shelters. Small triangular strongpoints at the corners were surrounded by anti-tank rail obstacles that continued around the position. The Mareth line was equipped with obsolescent 75 mm and 47 mm naval guns for anti-tank defence and a few new 25 mm anti-tank guns and infantry small arms. The artillery casemates with 75 mm guns and most of the blockhouses and casemates had embrasures for automatic weapons. In 1938 work the Mareth line was so important that work on coast defences was stopped and in 1939 the line was occupied by colonial divisions and some locally raised units. After the outbreak of the war, a line of advanced positions (avant-postes) was built on high ground at Aram 6.2 mi (10 km) south of the main line.