Thus was the scene set for depriving the Austrians of the one general who might have averted the multiple disasters that would fall upon their armies in the months of 1805. Because Charles argued so forcefully that ‘the Adige must therefore be considered the first and most preferable theatre of war’, it was only logical that the Archduke should take command of the 90,000-strong army in Italy, supported by his brother, the now not so inexperienced Archduke John in the Tyrol.

The Austrian forces north of the Alps were to coordinate their activities with the Russians, who numbered some 50,000 men under General Kutuzov. The 70,000 Austrian troops allotted to this theatre of operations were to be commanded by Mack. Charles instructed him to take special care to avoid confronting the French without the support of his Russian allies.

Mack, whose leadership in Italy in 1801 had not prevented the destruction of the pro-Austrian Neapolitan army, was a man whose imagination far outstripped his abilities. His qualities are hard to assess. He was a protégé of Lacy in the War of the Bavarian Succession and took part in the storming of Belgrade. His temperament appears to have been highly strung, and a fierce argument with Loudon after that campaign almost resulted in a court-martial.

In the campaigns in the Austrian Netherlands, Mack earned the praise of the Archduke Charles but the two men fundamentally disagreed on Austria’s strategy. Mack always favoured a more aggressive approach to the French. A severe head injury during one of the earlier campaigns had made him difficult to deal with and his Neapolitan troops were said to have contemplated doing away with him on many occasions during the disastrous campaign of 1801. Tolstoy has left us a very brief portrait of the ‘unfortunate Mack’ in War and Peace. It is not flattering.

Mack argued forcefully that the Austrians should push forward without waiting for the Russians and occupy Bavaria and its resources. When asked whether there was not a danger that his forces would be caught by a larger French army, he dismissed such warnings with the phrase : ‘All anxiety on this front is unfounded’. There was not ‘the slightest chance’ of the French intervening before the Russians arrived.

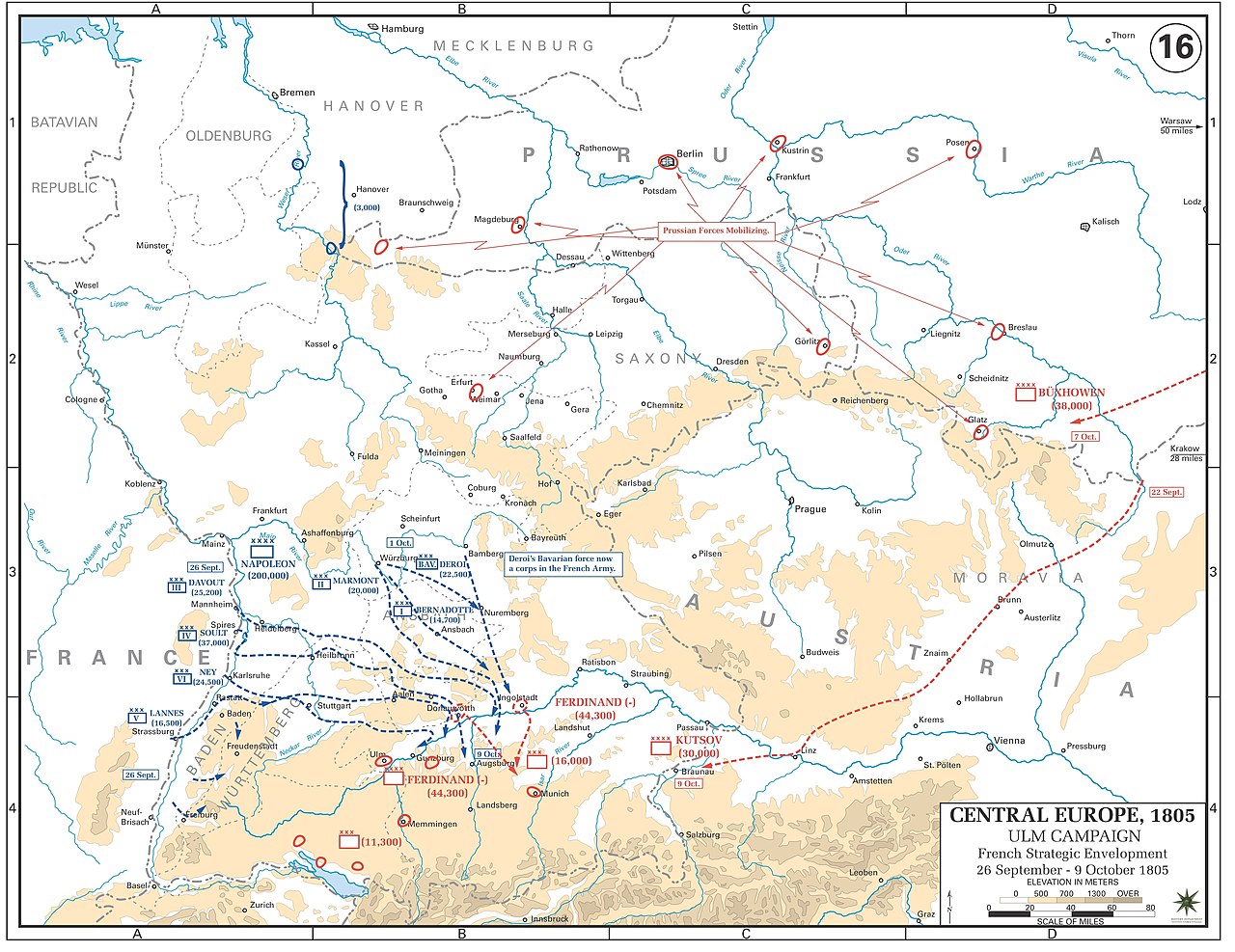

Mack drove his army into Bavaria, where the Elector carefully welcomed the Habsburg forces but made sure that his own troops were withdrawn to the valley of the Upper Main where eventually they would side with the French. It was one of many Bavarian moves that displayed traditional anti-Austrian proclivities. By the beginning of October 45,000 Austrian troops were strung along the 150-mile-long front between the Inn and Ulm. The supply train barely kept up with Mack’s progress and his artillery lagged far behind. But Mack was convinced his dispositions would confront the French as they attempted to break out of the Black Forest. Another Austrian force under Jellačić was approaching from the direction of the Tyrol, and a small but significant body of troops under Kienmayer, positioned to the rear of Mack’s force, would establish contact with General Kutuzov’s Russians.

It is hard to know whether Mack’s plans might have worked against an eighteenth-century opponent but Napoleon was arguably at the height of his powers as a continental strategist and he now moved to strike quickly and effectively against his principal continental foe. Contrary to the Archduke Charles’s supposition, Napoleon intended to strike the mortal blow at Vienna from north of the Alps. While Masséna was sent with 50,000 troops to face the Austrians in Italy, Napoleon marched his men to the Rhine, which they reached in twenty-nine days.

More than 75,000 infantry, 30,000 cavalry and 400 guns then marched from the Rhine to the Danube. One by one the German princes offered to help Napoleon. Since Napoleon’s coronation as Emperor of France the previous year, the German princes, or Reichfürsten, had increasingly orientated themselves towards Paris. Already in 1803, the Reichdeputationshauptschluss (the conclusion of the Reich deputation) had come to a decision in Regensburg that undermined Emperor Francis’s prerogatives. The ‘Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation’ over which Francis II was supposedly emperor had become nothing more than a polite fiction. Napoleon’s ambitions had illustrated vividly the shell of a concept which, its centuries-old history notwithstanding, could not survive the combination of French military might and revolutionary ideas. He had mediatised the German princes, altering the political map of their lands. In Vienna, the Emperor and court had seen the direction the wind was taking and already had begun to take steps to adjust to the new realities. The historic title of Holy Roman Emperor was becoming utterly meaningless and needed to be converted into something altogether more in keeping with the zeitgeist. Thus on 14 August 1804 barely two months after Napoleon had crowned himself Emperor of France, Francis II of the Holy Roman Empire became Emperor Francis I, Kaiser Franz I, of Austria.

Kaiser von Oesterreich

The new title of ‘Emperor of Austria’ was an invention. Francis was not interested in an ‘Empire of the Austrians’. The Empire was that of the Casa d’Austria (House of Austria) but in taking the double-headed eagle of the Holy Roman Empire to be the flag of what was now called the Austrian Empire, the Emperor was not sacrificing an iota of Imperial continuity. At the same time, the new concept gave emphasis to his ‘crown lands’: a slightly more cohesive and durable ship in which to sail in these stormy times than the loose grouping of unreliable and spineless German Reichfürste. His two brothers, Charles and John would exploit the opportunity to capitalise on Napoleon’s ambitions for Germany by stirring the pot of German nationalism and pushing Vienna towards leadership of the German ‘nation’. But in 1805, such ideas were barely moving and Kaiser Franz was certainly not fighting for ‘Germany’s honour’ as Mack’s forces gathered around Ulm. Mack’s army was to fight as it had always fought: for the dynasty.

By the second week of October, Napoleon was at the Danube. A short and sharp encounter at Wertingen between Murat’s cavalry and a force of 5,000 Austrians under Auffenberg revealed a demoralised and passive Habsburg army virtually unchanged since the disaster at Hohenlinden. This was a portent of things to come. Mack became obsessed with Ulm as ‘the key to half Germany’ and imagined that his forces were not only superior in numbers to the French but also in possession of all the topographical advantages. Ulm would be an offensive base for launching powerful actions against the French. Because the Russians would never have consented to serve under someone as lowly born as Mack, the Emperor Francis had appointed another archduke, the Archduke Ferdinand as titular head of Mack’s army.

The relationship between these two men left much to be desired. Mack and the Archduke Ferdinand did not cooperate even along the lines of the Archduke John and Lauer four years earlier, and the subordinate generals began to sense the tension between the two men. Mack, clearly insecure and over-challenged, confused activity with progress. Half-baked schemes to advance one unit here or there were quickly abandoned to be replaced with other schemes that were never fully carried out. All the while his opponent gathered his strength to pounce.

On 11 October the approaching Russian army was estimated to be nearly 200 miles away, or at least more than two weeks’ march distant. Napoleon realised that Mack, by concentrating his forces around Ulm, had actually made the job of defeating his opponents piecemeal much easier. At the same time, at Austrian headquarters, the grim reality of Mack’s position was becoming clearer by the hour. His scouts reported French units everywhere. Napoleon spurred his troops on, noting that but for Mack’s forces he and his army ‘would be in London now, avenging six centuries of outrage’.

On the same day at Albeck, a large force of Austrians, led by Mack, probing for indications of French deployment and for possible routes of a breakout, came into contact with the 5,000-strong division of General Dupont. In the ensuing action Mack managed to drive the isolated French back but he did not follow this up, perhaps because he was slightly wounded in the engagement. The victorious Austrian force simply returned to Ulm.

The Capitulation of Ulm, by Charles Thévenin

Schwarzenberg’s breakout. Ulm’s surrender

There the Archduke Ferdinand, increasingly exasperated by Mack, secretly planned with Prince Schwarzenberg a nocturnal breakout to the north with the 6,000 cavalry. These rode out of Ulm at midnight on 14 October hotly pursued by French dragoons but by two o’clock they had made good their getaway. The following day Mack attempted a further breakout but was checked by Marshal Ney at the Battle of Elchingen where the Austrians were forced to fall back to Ulm in driving rain.

Two days later, a staff officer of Napoleon, Ségur, reached Ulm and at three in the morning asked Mack to surrender. Mack played for time and agreed to surrender on the 25th if the Russians had not arrived. But the morale of the Austrians was beyond repair. A storm on the 18th caused the Danube to burst its banks and carry away much of the Austrian camp as well as the unburied corpses that had turned Ulm into a ‘pestilential latrine’.

A day later Napoleon summoned Mack to Elchingen. In return for a written declaration that the Russian army was still impossibly far away, the Austrian agreed to surrender his army and the city, ‘the Queen of the Danube’ to the French the following day. As the rain ceased, the sun came out to reveal a long column of Austrian soldiers winding out of Ulm. On the small hill overlooking the city a party of seventeen Austrian generals resplendent in their white tunics and scarlet breeches looked hesitantly at Napoleon. A French officer asked one of the Austrians to have the kindness to point out which of their number was their commander. The Austrian replied: ‘Moi monsieur: l’homme devant vous. Je suis le malheureux Mack en personne.’ When presenting his sword to Napoleon, the Frenchman savoured the moment and returned it with the words: ‘I return the general’s sword and ask him to pass on my best wishes to his Emperor’.

Francis was less obliging. On his return to Vienna, Mack was court-martialled, stripped of his rank and decorations, including the Maria Theresa Order, and then sentenced to a two-year spell in prison. The Habsburg ire was understandable. Mack had lost 51 battalions of infantry, 18 squadrons of cavalry and 60 guns. The Archduke Ferdinand reached Bohemia with barely 2,000 cavalry and the Austrian forces under Jellačić advancing from the Tyrol, unsupported and outnumbered, were forced to surrender on 14 November. The road to Vienna now lay wide open and an army of 75,000 Austrian troops, fully equipped to guard its approaches, no longer existed.

Marshal Kutuzov’s Russian soldiers were still several days’ march away but the forces they had hoped to link up with had literally vanished into thin air. Kutuzov had achieved prodigious feats of human endurance in marching his army from distant Galicia to the Danube valley. Thousands of stragglers had had to be abandoned and the footwear of most of those who had reached Austria was sorely in need of repair. By the time Kutuzov reached Braunau on 27 October, rumours of the disaster at Ulm were beginning to circulate.

The plight of Kutuzov now merged with the plight of defenceless Vienna. While Napoleon detached significant forces to guard the Alps and prevent the forces of the Archduke Charles marching to the relief of the Imperial capital, he manoeuvred the bulk of his army to cross Bavaria to find and annihilate the Russians.

Kutuzov, who had linked up with some Austrian remnants, abandoned Braunau and withdrew to a tighter line of defence 60 miles east on the banks of the river Enns. On the last day of October a firefight broke out between a large French force and some Austrians supported by Russian light troops at Traun. The allies conducted a disciplined withdrawal. As Kutuzov retreated along the Danube, he paused at Amstetten. While a French force under Mortier was dispatched to the north bank of the Danube at Linz to find the Russians, Kutuzov was reinforced by another Russian column, which had marched from the Turkish frontier.

The Russian scouts reported Mortier’s position and, with the help of an able Austrian staff officer called Schmidt, Kutuzov drew up plans to defeat Mortier under the ruins of Durnstein castle so beloved of legend as the place where Richard the Lionheart was rescued by the minstrel Blondel. The skirmish was short but sharp: the gifted Schmidt was one of the fatalities but after a fierce fight the French withdrew to the south bank under the cover of darkness.

Lannes seizes the Wiener Donaubrücke

Napoleon immediately drew up plans to bring more of his army over the Danube to the north side and so prevent the Russians from linking up with any Austrians positioned around Vienna. The key to this strategy was to be the seizure of the Wiener Donaubrücke, a series of very fragile structures which carried the main road across the river to the north of Vienna.

Though the bridge was primed for destruction and guarded by the Austrians, the French generals simply walked across and announced to the astonished Austrians that, as an armistice had been declared, there was simply no point in any more blood being spilt. It struck one Austrian officer that all was not well when he saw the French grenadiers marching in step across the bridge but Marshal Lannes assured him his men were simply briskly marching ‘to keep warm’ in the cold temperatures.

The Austrian commander at the Donaubrücke had been retired for fifteen years. Count Auersperg was certainly not in the first flush of youthful energy. But as a later historian has pointed out, Auersperg’s failure to defend the bridge denotes a failure ‘of the will and intellect, if not downright imbecility’. Even the French could not believe it. But Lannes was after all a Gascon.

The passage of Lannes over the Danube not only threatened Vienna, it severely compromised Kutuzov. Moreover, if Vienna were lost, Austrian troops coming up from south of the Alps would face a formidable obstacle in their path before they could link up with their Russian allies.

Kutuzov moved as rapidly as he could to get his army out of harm’s way and withdrew north while his colleague, Bagration, threw up a screen at Schöngrabern, which Murat mistook for the entire Russian army. He sent an envoy to Kutuzov offering an armistice ‘now there was peace between France and Austria’. Bagration was not taken in by the lie and Kutuzov paid the French back in their own coin by sending two staff officers to discuss terms and drag the talks out for 24 hours while Kutuzov got his army safely away. When Napoleon heard of the ‘armistice’ he was incandescent and sent a swingeing note to Murat who, when he received it, began to wake up to the fact that the Russians in front of him were not as numerous as he had first thought. By the time Murat attacked it was almost dark and the Russians detonated Schöngrabern to create a formidable obstacle to any pursuit. Covered by a regiment of Jaeger, Bagration confused the French sufficiently for Kutuzov to pass safely into Moravia by the following morning. By the time Napoleon reached Znaim to settle things with Murat his mood had blackened, not least because he had just been given an account of the Battle of Trafalgar.

Kutuzov continued to Brünn (today Brno in Moravia) where, joined by a strong Austrian force under Liechtenstein, he managed to bring his forces up to a formidable 80,000 men. Moreover, further reinforcements were on their way. Ten thousand elite troops of the Russian Imperial Guard were at Olmütz (Olomouc) in northern Moravia, having marched all the way from St Petersburg. More troops were marching from Poland and nearly 10,000 Austrians were assembled under the Archduke Ferdinand in Bohemia.

Above all, the Archduke Charles had managed to bring his army out of Italy in brilliant style, suddenly turning and attacking his pursuers. Meanwhile in Moravia, Napoleon was greeted with great warmth by the local population, famous for the beauty of their womenfolk, their native charm and wit. The Moravians found the French an altogether more agreeable occupying force after the Russians. But the French army was not in brilliant shape. Exhausted by its forced marches and far away from home, it needed a swift victory. If it were to retain its cohesion it would be as well to fight the decisive battle as soon as possible.