TRIUMPHS

The tradition of holding triumphs was well established in the Republic, and especially so during the period of heavy fighting following the Second Punic War. When a triumph was awarded, a major public celebration followed in which the general, now hailed imperator, decorated the best performing and bravest soldiers, handing out the booty to his men and sometimes also to the general public, any surplus paying for public works. Then the general would ride into Rome in his chariot with his family on horseback, followed by the rest of the army on foot. The climax was the execution of prisoners and religious ceremonies of thanksgiving at the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill.

Thirty-nine such events were celebrated between 200 and 167 BC, an average of more than one a year, and a further 46 from then till 91 BC.64 The consul Gnaeus Manlius Vulso was one recipient. He committed the outrageous act of going to war on his own accord on the Galatian Gauls in Asia so that he had the chance of a prestigious victory to brag about. And that was exactly what he got. Though he was censured for his actions, Vulso’s opponents soon relented when he was voted a triumph by the Senate in 187 BC and was able to parade vast quantities of gold and silver through Rome while his soldiers sang songs in his praise.

In 168 BC Aemilius Paullus held a three-day triumph to celebrate his defeat of Perseus of Macedon at Pydna that year. It was a particularly pointed gesture since he was the son of the consul of the same name killed at Cannae: he had restored his family’s reputation. Enormous quantities of gold and silver seized from the defeated king were paraded before the Romans, after which Perseus’ children and their attendants were forced to walk along and hold out their hands in supplication, followed by the bewildered and humiliated Perseus himself. The climax was the sight of Aemilius in his chariot, accompanied by his army, the soldiers singing traditional ballads interspersed with bouts of mockery, as well as songs celebrating their victory and Aemilius’ leadership. One can easily imagine the raucous and noisy exultation of Aemilius’ troops as they pranced through Rome boasting of their achievements.

Some generals had an eye for a more permanent monument. In 119 BC the moneyer Marcus Furius issued an unusual silver denarius. Instead of the customary bust of Roma, the coin bore the head of Janus, and on the reverse a figure of Roma crowning a trophy. It commemorated a victory won over the Gaulish Allobroges and Arverni tribes in 121 BC by the consuls Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus (consul in 122 BC) and Quintus Fabius Maximus (121 BC), the latter completing the campaign the following year and being awarded a triumph and the name Allobrogicus. Out of the booty Fabius Maximus paid for a triumphal arch known as the Fornix Fabianus to span the Via Sacra in the Roman forum. Fragments of the arch are still visible in the forum today, close to the remains of the later temple of the deified Julius Caesar. It was an interesting turnaround for Fabius Maximus. As a youth he had been considered the ‘most disreputable’ member of his generation, yet military success transformed his status. He ended up a ‘most distinguished and respectable’ old man.

The prospect of a triumph was so attractive that every Roman general was desperate to have one to add to his own and his family’s glory. In the aftermath of the Second Punic War so many were staged that eventually, at some point between 180 and 143 BC, a law was passed to place a minimum requirement that 5,000 enemy soldiers be killed before a triumph could be voted. Triumphs were also expensive – hugely so. No wonder Suetonius said that Caesar paid for his with ‘barefaced pillage’. Some prisoners made a great show of their capitulation in advance of these great events. Vercingetorix, the Gaulish king who had led the war against Caesar’s conquest of Gaul, surrendered at Alesia. In 46 BC, after ‘putting on his most beautiful armour and decorating his horse [he] rode out through the gate. He made a circuit around Caesar, who remained seated, and leaped down from his horse, stripping off his suit of armour’, well aware that because of his height ‘he made an extremely imposing figure’. Vercingetorix then sat quite still beside Caesar until he was led off to await the triumph in Rome, where he was publicly executed.

The Gaulish triumph turned out to be the first of five held by the vainglorious Caesar, four of them in little more than a month. The occasion was almost a disaster because he nearly fell from his chariot after the axle broke. Caesar’s triumph celebrating his defeat of Pharnaces II of Pontus climaxed with 40 elephants carrying lamps to light his way, and his famously alliterative showcase inscription veni, vidi, vici (‘I came, I saw, I conquered’) which was displayed during the procession. During the triumph to celebrate the war in Gaul one of the most memorable moments came when his soldiers burst into song:

All the Gauls did Caesar vanquish, Nicomedes vanquished him;

Lo! now Caesar rides in triumph, victor over all the Gauls,

Nicomedes does not triumph, who subdued the conqueror.

This was a salacious reference to rumours that as a young man Caesar had had a sexual relationship with Nicomedes IV of Bithynia. Such jibes seem to have been a common occurrence during triumphs.

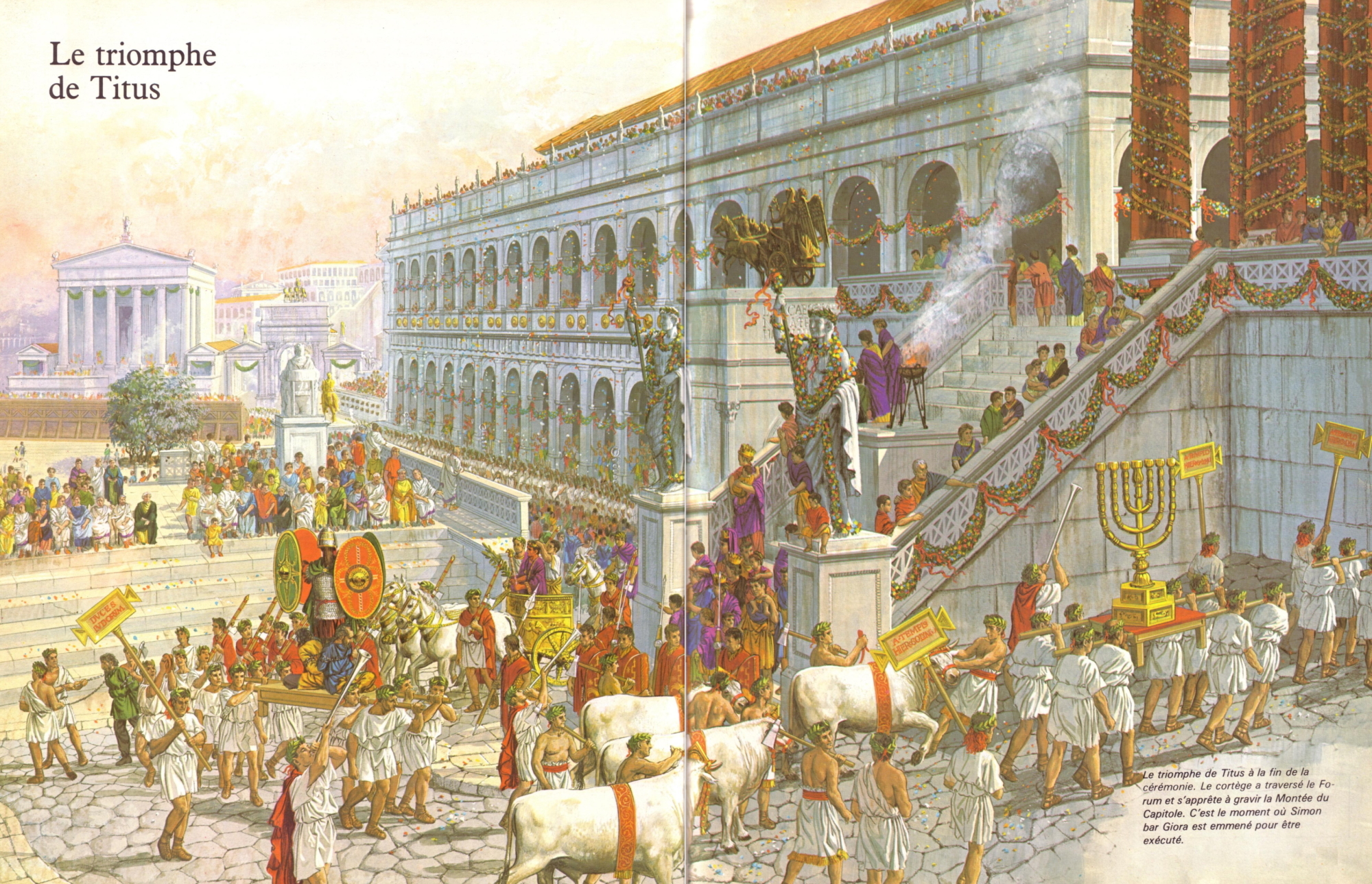

One of the greatest descriptions of a Roman triumph comes from Josephus, who saw the festivities put on by the emperor Vespasian and his son Titus in Rome in 71 to commemorate the Jewish War after Titus’ return to the capital. Josephus depicts a scene like that from an epic motion picture, and the comparison is not inappropriate. The occasion was designed to be as magnificent and as theatrical a spectacle as possible. The two men spent the night in the temple of Isis, near the upper palace on the Palatine Hill. In the morning they donned robes of purple silk and laurel wreaths before going out to be greeted by the senators and the equestrians. The two men were seated on ivory chairs as the army hailed them, before Vespasian raised his hand as the sign for them to fall silent. He drew a robe over his head in the manner of a priest and said the appropriate prayers, followed by Titus. Vespasian made a speech – which must realistically have been almost inaudible to the assembled troops – and sent the men off to a celebratory breakfast. He and Titus then left to have breakfast themselves before changing into triumphal robes, and made sacrifices to the gods. Next they walked through the theatres of Marcellus, Balbus and Pompey in the Field of Mars so that the crowds gathered in the buildings could get a better look at them.

The proceedings had of course barely started. Josephus said it was difficult to find words that could possibly describe the magnificence on display. He saw works of art and all manner of riches that provided a graphic illustration of the power and wealth of the Roman Empire. Given that, only a few years previously, Rome had been badly damaged by the fighting during the Civil War, the visual impact must have been even greater. Josephus compared the parade to a flowing river of floats laden with gold, silver and ivory as jewels, artefacts and statues of gods were carried past. As Vespasian and Titus had started the day wearing purple robes, so did purple feature prominently because of the enormous expense involved in antiquity in manufacturing the dye. There were tapestries of purple, and the men driving the animals in the parade wore purple uniforms. Even the prisoners had been dressed in expensive clothing, with the distasteful purpose of diverting attention from their injuries.

Josephus was more intrigued by the way the floats had been constructed. Some had four levels, one above another, and curtains with gold and ivory fittings. The purpose was to provide a mobile depiction of the progress of the war. In this respect it too was almost cinematic, recreating in visual form the sort of scenes and events more normally experienced by ordinary Romans in the epic poetry of Virgil and Homer. These included battles, images of ravaged enemy territory and of people being captured and imprisoned, cities under siege, the Roman army bursting in through the walls and massacring the inhabitants, the destruction of houses and temples, and rivers flowing through a devastated land on fire. The crowd would have recognized instantly the echoes of the imagery of Rome’s past wars, climaxing in Augustus’ victory over Antony and Cleopatra and ending on civil war, on the mythical shield fashioned by Vulcan for Aeneas and described in book 8 of Virgil’s Aeneid.

In the contemporary setting, the triumph was designed to celebrate and showcase the success of the new regime that had followed the Civil War of 68–9 and before that the chaotic and disastrous reign of Nero. It also bought into the Romans’ vision of themselves as the divinely ordained conquerors of the world. The graphic depictions of brutality were entirely in harmony with the way the Romans venerated and enjoyed violence. Josephus, despite being a Jew himself, unhesitatingly blamed the Jews for bringing this all upon themselves.

The centrepiece of Vespasian and Titus’ triumphal procession was the treasure seized from the temple at Jerusalem, including a gold table and seven menorah candelabras. One of these at least was made of gold and was designed to hold lamps on each of its seven branches. The final component in the display of spoils was a book of Jewish laws. At the rear came figures of Victory made of ivory and gold, and finally Vespasian and Titus themselves in chariots, with Vespasian’s younger son Domitian riding alongside. The procession’s destination was the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, which had been rebuilt since it was set on fire during the Civil War in 69 (it would be burned again in 80). The triumph had now reached its climax. Simon bar Giora, the principal leader of the Jewish forces, was beaten and dragged into the forum where he was executed. With this done, and sacrifices performed, Vespasian and his sons returned to the palace while the rest of the city enjoyed what remained of the day.

Ironically, the war was not even yet over. Legio X Fretensis had been left behind to mop up any remaining Jewish strongholds, and it was not until the siege and fall of Masada in 74 that the conflict ended. Moreover, it would be a mistake to assume the soldiers were automatically cheering on Titus and his father. Soldiers were known habitually to poke fun at their generals during triumphs, as Caesar’s men had done. In around 84, during the reign of Domitian, the poet Martial described how the new emperor had been subjected to jests during his own triumphs, and asserted that it was no bad thing for a general to be the butt of jokes.

Vespasian followed up the triumph with the construction of a temple of Pax on a large site across the forum from the Palatine Hill and close to Augustus’ temple of Mars Ultor (‘the Avenger’). The temple became an art gallery but also displayed some of the Jewish treasures. Several years later, after Vespasian died and Titus succeeded him, the Arch of Titus was erected on the Via Sacra leading south from the forum, recalling Fabius Maximus’ arch from two centuries before. Today its reliefs depicting the triumph of 71, including the Jewish booty being carried in the procession, and Titus in his chariot, are still in situ.

LAUGHING STOCKS

Some campaigns risked humiliating the emperor and his army. Caligula’s notorious attempt to invade Britain in 40 – something Augustus had also considered – was recalled in Roman military lore as an occasion like no other. By that point in Caligula’s reign a serious illness and a complete psychological inability to cope with the extent of his power were beginning to have a dramatic effect. Caligula arrived at the English Channel on the north coast of Gaul and ordered his soldiers to line up on the sand, equipped with ballistas and other artillery. He boarded a trireme which sailed out to sea and then returned. Once back on the shore he instructed his soldiers to attack by gathering up shells from the beach. These were his ‘booty’, which would be taken back to Rome. He was delighted, believing he had ‘enslaved the ocean’, and in celebration set up a lighthouse to guide ships. The soldiers must have been not only incredulous but appalled at the lack of any opportunity to seize real booty, a blow doubtless softened by a gift of 100 denarii each (about five months’ pay at the time). The episode was of course an absurdity – but at some point serious preparations must have been put together, because after Caligula’s assassination in 41 it was possible for his successor Claudius to carry out a real invasion.

However, the Claudian invasion of Britain in 43 also came close to falling apart before it had even started. Anxious to throw off his reputation as the family idiot and the stooge of the praetorians who had made him emperor two years earlier, Claudius had ordered the expedition because he was keen to show the Roman army and the Roman people that he was worthy of being emperor. Almost a century earlier Julius Caesar had invaded Britain twice, but had not succeeded in holding on to the island, if indeed he had ever intended to. Claudius believed a military triumph would be the best way of achieving the necessary prestige to consolidate his hold on power. Matching, and exceeding, his glorious forebear’s achievements (Claudius was descended from Caesar’s great-niece Octavia, sister of Augustus) would be an excellent means of doing that.

Claudius was handed a pretext on a plate when a tribal leader called Verica, ousted by his rivals, turned up in Rome asking him to intervene. Claudius placed the invading army under the command of Aulus Plautius, ‘a senator of great renown’, but despite the man’s reputation he struggled to persuade the soldiers to take to the ships and cross over to Britain. Working back from later evidence dating to the time of the Boudican Revolt, it is possible to be reasonably sure that all or most of the II Augusta, VIIII Hispana, XIIII Gemina and XX legions were involved, together with vexillations of other legions, detachments of praetorians and about the same number of auxiliaries. This amounted to in total roughly 40–50,000 men, all of whom had to be gathered on the Gaulish coast to make the voyage. Roman soldiers were notoriously superstitious and the occasion could not, in their eyes, have been more inauspicious. They were, said Dio, ‘indignant at the thought of carrying on a campaign beyond the limits of the known world’ and refused to embark. Fortunately, Plautius’ entourage included an imperial freedman called Narcissus, one of Claudius’ closest advisers.

Claudius was still in Rome, waiting for news that the invasion had been successful, at which point he would travel to Britain to lead the army into the Britons’ principal settlement at Colchester. In the meantime his freedman Narcissus loyally stood in for the emperor and decided to address the gathered force. This appalled the soldiers, who were disgusted at the thought of a former slave exhorting them to do their duty. They barracked and heckled Narcissus, who was unable to get a single word out. The climax came when they remembered that at the festival of the Saturnalia in December it was customary for slaves and masters to swap roles. They promptly saw the amusing side of the incident and began chanting ‘Io Saturnalia’, before deciding that they had better decide for themselves to get on with the job, rather than endure any more humiliation. They abandoned their protests and agreed to cross the Channel to Britain. The delay caused by their complaining had pushed the invasion back until late in the summer, but the soldiers were emboldened when a flash of lightning rose ‘in the east and shot across to the west’. It seemed to be showing them the way to Britain, and since lightning bolts were thought to be sent down by Jupiter, it was all they needed to feel optimistic. The invasion went ahead and Britain, or at least most of it, would remain a province of Rome until 410.

A GRAND TRADITION

Although the later Empire is outside the scope of most of this book, there were incidents where Rome’s soldiers managed remarkable feats in the face of adversity honouring the grand tradition of their forebears. From the mid-second century on Rome was increasingly on the back foot. Conquest and the opportunity for glory belonged mainly to the past, replaced by defensive and civil wars.

Ammianus Marcellinus is our best source for events in the third quarter of the fourth century. He recounted how in 359, during the siege of the city of Amida in Mesopotamia by Shapur II of Persia and where he was present, two Gallic legions were enraged by the way the Persians were carrying off Roman captives to their camp. They demanded to be allowed to attack the Persians, threatening to kill their own officers if refused. An agreement was reached and the Gallic soldiers burst out through a gate, and caused mayhem in the Persian camp, killing the sleeping enemy. Even when the remaining Persians woke up and fought back, the Gauls fought back bravely and with absolute determination. Despite their losses they only retreated slowly, and re-entered the city at dawn. The emperor Constantius II (337–61) ordered that statues of the Gallic officers in full armour were to be erected in their honour at Edessa. The siege, however, ended in disaster when the Persians captured it, and killed everyone left.

A few years later Constantius’ successor, Julian the Apostate (360– 3), took the war into Persia, initially with great success. After crossing the Tigris with his army in 363, he soon after met the Persians in battle. Showing brilliant leadership Julian kept encouraging his men until the Persian line broke. The Persians broke into retreat and fled back to the city of Ctesiphon, the Roman soldiers having to be restrained from following them through the gates. Ammianus compared their heroics to those of Hector and Achilles, and recorded the Persian losses at 2,500 for the cost of only 70 Romans.

Roman soldiers, under the right circumstances and leadership, were capable of extraordinary achievements and rightfully gained an unsurpassed reputation for resilience and resourcefulness. These were qualities that belonged to a tradition stretching back to Rome’s earliest days, and explained how the city had risen from obscurity to unmatched power and success. Inspired by the feats of his predecessors, every Roman soldier knew he had a great deal to live up to, and many met the challenge. However, nothing could alter the fact that military glory and success were only won with violence, sometimes on a horrific scale. The Roman army’s history was punctuated by innumerable tales of extreme brutality.