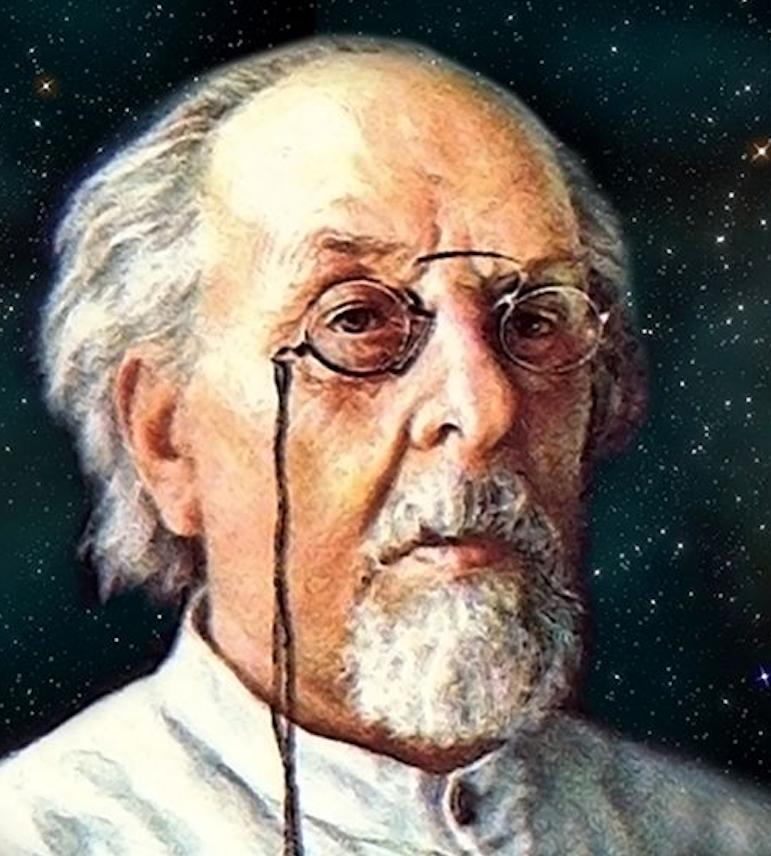

Tsiolkovsky

Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky was born on September 17, 1857, in the Russian village of Izhevskoye in the rural province of Ryazan, one-hundred twenty miles (195 km) southeast of Moscow. As a young boy, he was full of energy and displayed an eager quest for knowledge. But at age ten he was stricken with scarlet fever, which left him with a severe deafness problem for the rest of his life. Konstantin called his mother the spark of the family, and the one who guided him in coping with his disability. Her early death in 1870, when he was only thirteen, was a most unfortunate hindrance to his developing years.

Shortly thereafter, Konstantin dropped out of school. So the years from 1868 to 1871 marked an understandably frustrating period in the young adolescent’s life. With first the handicap and then the loss of his mother, he cut himself off from the surrounding world. Nevertheless, at age fourteen, he awakened and his appetite for self-education took sudden acceleration.

Tsiolkovsky’s father Eduard must be given credit for holding the family together, and doing what he could on limited means. A forester by trade, he lost his job in 1867, then becoming a clerk. While not particularly successful in his professions, he was a man of strong integrity, devoted to his children, and a believer in hard work. Young Tsiolkovsky took his parents’ positive traits and applied his own brilliant mind, especially to a craving for mathematics, physics, astronomy, chemistry, and mechanical creations.

In 1874, when Konstantin was age sixteen, Eduard sent him to Moscow for self-study in the hope that this would lead to entrance to a technical school. He was on starvation wages, but his needs were few and desire for learning high. He continued overcoming his handicap, spending his days at the renowned Rumyantsev National Library and delving into books on mathematics and the sciences. He was also befriended by an influential, eccentric philosopher of the day by the name of Nikolai Fyodorov.

Fyodorov was known for mentoring young men in libraries who were poor – students like Tsiolkovsky. Fyodorov was a believer in a philosophy known as Russian “cosmism,” which espoused that a type of human immortality and salvation could be found through travel to the cosmos: outer space and its moons, planets, and stars. Humans were not to permanently die, but be reconstituted into another kind of life form and settle throughout the universe. Spaceflight and advanced technology were key tenants of the philosophy. So it was during this period that Konstantin was first exposed to visions of space exploration. He would say in later years that the writings of Jules Verne were also an inspiration.

After three years in Moscow, Konstantin returned to his hometown as a tutor. In 1879, he passed the examination required to become a teacher, and the next year took a math and science teaching position in provincial Borovsk. There he continued his readings, began some experiments in a home laboratory, and started recording his findings in a methodical manner. But his ruminations, calculations, and sketches at this time were on a wide variety of scientific problems. He was not yet mentioning rocketry and spaceflight.

Tsiolkovsky would always prove to be a superb teacher; he was one who could present material to his students with enthusiasm. He incorporated the latest teaching methods, and believed in practical experimentation to go along with theory and bookwork.

During his time in Borovsk, he married Varvara Sokolova, who he’d met during his Moscow years. She would prove to be a stalwart supporter of his work during their lifetime together. They would have seven children, although tragically four of these offspring would die during adolescence.

In 1881, at age twenty-four, Konstantin sent a report on the kinetic theory of gases to the Society of Physics and Chemistry in St. Petersburg. While his findings were not earth-shattering, and indeed had already been formulated by others, the esteemed scientists there saw that he had potential.

Then in 1883 he wrote a short work – more a long diary entry and unpublished at the time – titled “Free Space.” In it, he demonstrated a true understanding of the principle of obtaining motion in the vacuum of space by the reaction method. He also described concepts of life in space and zero gravity, drew a primitive design of a spacecraft, and proposed a gyroscope for stabilizing a flying vehicle.

Tsiolkovsky spent the next fifteen years testing the physics and mathematics of his various theories, all the time becoming somewhat more known in Russia through publication of articles in newspapers and his contacts with the Society. But he had many scientific interests at this stage of life. He constructed a wind tunnel – thought to be Russia’s first – and explored topics like air resistance and dirigibles (blimps or zeppelins).

In 1892, Konstantin gained a higher teaching position in the provincial town of Kaluga, to which he moved, living there the rest of his life. The home he eventually resided in with his family had an upstairs workshop. During his free time and among his handmade lathes, wind tunnel, tools, and assorted machines, he theorized and experimented on his inventions.

In 1898, he published research on air resistance in a scientific journal. Due to the interest generated, Konstantin submitted a request for funding in 1899 to the Imperial Academy of Sciences to support further efforts in this field. The Academy granted him some minor funds to continue studies. It was during these very last few years of the 19th century that Tsiolkovsky decided to also turn more of his attention toward solving the problems of the rocket, the reaction process, and flight in space.

Konstantin’s notes show that, from 1898 to 1903, he developed his famous mathematical equation (or formula) the “rocket equation” –which describes rocket acceleration in terms of (1) the velocity of gas exiting from the engine nozzle, and, (2) the decreasing mass a rocket has after liftoff due to consumption of propellants. While others in the 19th century had derived the basic equation, and used it in analysis of flight paths of various objects including rockets, Tsiolkovsky was the first to thoroughly describe and analyze all aspects of this fundamental formula of rocketry. His notes also reveal that he became convinced only liquid propellants – and not any of the known powder combinations – could provide the thrust necessary to launch a rocket-type vehicle out of the atmosphere.

He summed up his findings and sent them to the Russian journal Naootchnoe Obozreniye (Scientific Review). In 1903, Konstantin’s work would be published under an article titled “Investigation of World Spaces by Reactive Vehicles.”

This article was truly significant, as Tsiolkovsky described his rocket equation and the reaction rocket as the necessary vehicle for traveling to and in space. The vehicle he proposed for the mission was elongated to produce little aerodynamic drag, mixed and fired its propellants together in a combustion chamber, and had a compartment for passengers. He addressed multiple-stages as necessary to reach space, and also the propellants liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen as the most powerful combination. He continued on to provide detailed mathematical calculations on the required escape velocity that his liquid-propellant rocket would have to achieve to break free from Earth’s gravitational force. This was all trailblazing material for the time. Sergei Korolev, in later years, would also give Tsiolkovsky credit for these ideas: a flared cone for the rocket nozzle, a combustion chamber to which propellants were supplied by pumps, and foreseeing the need for regenerative cooling.

After the article, Tsiolkovsky’s findings were not given much recognition of note. Konstantin would later blame this lack of early publicity on his being a self-taught scientist, laboring in the provincial town of Kaluga This was at a time when science was controlled by what he called the Tsarist cliques in the main Russian cities of Moscow and St. Petersburg. There was truth to his charges. Discouraged at trying to publish rocket theory, he would actually focus, over the first decade of the 20th century, on improving his dirigible designs and solving problems in the growing science of aeronautics.

However, he and his rocket work were not going totally unnoticed. In 1912, a Russian aeronautics journal republished the 1903 paper, having Tsiolkovsky expand on functions such as air resistance and atmospheric pressures on the rocket. Two years later, he self-published a supplement in which he detailed types of propellants to use with rocket engines, as well as further exploring space travel. These publications fit in nicely with a noteworthy pre-revolutionary surge of interest in all types of flight among the Russian populace. Works of popular science and space fiction were particularly sought after by enthusiasts.

The First World War erupted in August 1914, overwhelming all other events. At age fifty-six, Tsiolkovsky was too old to be considered for active duty with the military. Through the war years, Konstantin the genius would soldier on in Kaluga, teaching his pupils during the day, and after school doing research and theorizing on his various interests. In regards to rocketry and space exploration, he wrote science-fiction novels, technical papers, and short pamphlets, not only attempting to popularize these subjects, but to supplement his meager income.

But his lack of success in getting more widespread scientific recognition actually led to states of depression and withdrawal around 1916. Contributing factors were also his low teacher’s salary and failure to get any consistent financing for his experiments.

The Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, and the ensuing turmoil that lasted up to the formation of the Soviet Union in late 1922, produced chaos that did not enhance most scientific work. The battle to the death between the remnants of the Tsarist regime (White Armies) and the Bolsheviks (Reds) would bring both positives and negatives to Tsiolkovsky’s fortunes.

On the upside, Konstantin benefitted from several initiatives. In 1918, the new regime’s revamped school system resulted in a better teaching opportunity. He also began receiving a small local education pension.

The revolutionary era had produced a thirsting among the masses for new ideas, science, and technology – all a reaction to discarding the primitive system of the tsars. There was hope for leading better lives. Tsiolkovsky’s ideas on space and aeronautics paralleled the new themes and dreams nicely. Demand for his talents would lead to Konstantin giving lectures on rockets and air flight at local universities, with this boosting his name recognition.

In July 1918, the Bolsheviks established a Socialist Academy of Social Studies as a center to promote Marxist ideas. One of the Academy’s policies was to be more egalitarian in the nature of who could enter its ranks. This standard immediately appealed to Tsiolkovsky, who with no formal education, had always felt shunned by the Imperial Academy elites.

In August 1918, Konstantin sent a letter to the new Socialist Academy promoting his ideas. The initiative was mainly a bid to get monetary support for his work. There has never been any evidence that Tsiolkovsky was politically active; he was first and foremost a pure scientist and theorist simply looking for a funding source. Shortly thereafter, he would be elected as a junior member to the organization for recognition of his achievements. He even started receiving a monthly stipend for this honor.

But in 1919, the revolution demonstrated the turmoil it could bring to individual lives. Konstantin’s initiative to the Academy took a disastrous turn when the money started drying up and he vocally complained; he thus fell into disfavor. He would next find himself ejected from the organization in July 1919, most likely for not being political enough in his views.

Tsiolkovsky’s fortunes continued to plummet. He would be arrested in November 1919 by the Soviet secret police and shockingly jailed in the notorious Lubianka prison in Moscow, charged with being a spy for the White Russians. He received a one-year sentence to a labor camp. Thankfully, a high-level official intervened and ordered him freed while he was still in Moscow, ruling that a former associate of Tsiolkovsky’s was unstable and had made false charges. But Konstantin barely survived the whole ordeal, staggering around the huge city after his release in a daze. He finally found his way to a train station and made his way back to Kaluga.

The year 1921 marked the beginning of the New Economic Policy (NEP) in Russia; this a term used by the Bolsheviks for policies attempted from 1921 to 1927 to rejuvenate the generally pathetic state of affairs. One of the tenants of the NEP was to try to improve the lives of scientists. With his constant promotion of rockets and spaceflight, and dirigibles and aeronautics in general, Konstantin would find assistance under this policy.

The Council of People’s Commissars voted him a small government pension for his lifelong works. Added to his local education pension, this new state-level pension meant he could retire from teaching and truly devote himself to research and writing creativity He would receive these benefits the rest of his life, albeit irregularly. Another problem was that the two pensions really didn’t amount to much. Money troubles always plagued Konstantin, right up to his last years.

But Tsiolkovsky’s life had commenced an upward path by the early 1920s. With his retirement from the schoolhouse, he could focus on the cosmos – and his timing was perfect, as during the 1920s significant numbers of people were embracing rocketry and space travel.

Two main promoters of the subjects, in the Soviet Union, were a physics professor and editor of popular journals, Iakov I. Perel’man, and, another professor and space historian by the name of Nikolai Alexsevitch Rynin. Both men were inspired by the ideas of Tsiolkovsky, were in contact with him, and as part of their publications turned the genius’s theories and technical minutia into popular works for the masses.

Out of this popularization of space would come an informal network of believers, who then provided funding for Tsiolkovsky’s writing efforts. These money sources allowed the publication and dissemination of his prolific works during the decade.

In October 1923, attention came Konstantin’s way when the central government newspaper Investiia published a short article by an anonymous author that lauded the just released book Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen (The Rocket into Interplanetary Space) by Hermann Oberth. Praise was heaped upon the German for his superb writing in regards to rocketry and spaceflight theory. Tsiolkovsky was given no mention or credit whatsoever in the piece.

This indignity spurred popular writers like Perel’man to rush to Tsiolkovsky’s defense, noting in a spate of articles the priority of the 1903 “Investigation.” Konstantin then found himself, in the last phase of his life, with recognition he never imagined. He personally got caught up in the wave; he was motivated to ensure his rightful place in rocket and space history.

He started by convincing some associates to assist in republishing an updated version of his 1903 work under the new title “A Rocket into Cosmic Space.” In 1924, the thirty-two page brochure was distributed mainly in Moscow, and proved highly popular among space enthusiasts.

Significant Russian interest in rockets and space travel in the 1920s was made apparent by a series of exhibitions that were sponsored by the Interplanetary Section of the Moscow Society of Inventors in 1927. Exhibits featured displays on Jules Verne, Robert Goddard, Oberth, and of course the homegrown hero Tsiolkovsky.

During the last eight years of his life, Konstantin was cast in the role of the wise and respected old “rocket sage” residing at his Kaluga outpost, in contact with and a hero to a new generation of Russian rocketeers. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, he was sought out for advice by enthusiasts of the newly formed Gas Dynamics Laboratory of Leningrad (St. Petersburg) and Group for the Study of Reaction Motors in Moscow – the two historic groups which formed the basic organizational pillars of Russian modern rocketry.

Tsiolkovsky was a “living legend” and still publishing voluminously, but reaching the physical end. His works in later years included The Reaction Engine (1927–28), A New Aeroplane (1928), Jet-propelled Aeroplane (1929), The Theory of the Jet-Engine (1930–34), The Maximum Speed of a Rocket (1931–33), and a massive volume on multi-stage rockets titled Space Rocket Trains (1924–1934).

In the early 1930s, Konstantin was bestowed with an even higher level of recognition when the Stalinist state embraced him as a national hero and founding father of cosmonautics. He was honored as an example of a scientist who had struggled against adversity and could excel in the socialist system. The state also decided to finally start sponsoring his work.

Inserted here is a most interesting story concerning the origins of the term cosmonautique (“cosmonautics” equates to “astronautics”). In November 1933, the term itself was first introduced by Ary Sternfeld in his manuscript “Initiation à la Cosmonautique” (Introduction of Cosmonautics). Sternfeld was originally from Poland, studied and lived in France in the 1920s and early 1930s, then immigrated to the Soviet Union – attracted by the country’s socialist ideals – in 1935. While still living in Paris in 1934, he had been awarded the REP-Hirsch Prize for his manuscript. In the Soviet Union, he would find himself mostly relegated to working in his cosmonautics field of expertise in solitude, with his achievements receiving close to nil recognition the remainder of his life.

In 1932, the Communist Party awarded Tsiolkovsky the Order of the Red Banner of Labor, and his meager pension was doubled in size. He would show his appreciation by bequeathing all his personal papers and works to the state and party. In 1935, Konstantin was invited to give the feature speech at the May Day Parade in Moscow. Too frail and sick to attend, he taped a message that was broadcast over Red Square as planes and dirigibles flew overhead in formation – all a most dramatic presentation.

The late acclaim for Tsiolkovsky came despite a decline in interest among the populace toward space in the mid-1930s. Soviet leadership had directed a turn toward more practical rocketry, all due to the very real concerns associated with Hitler and the Nazis coming to power in Germany.

The visionary Tsiolkovsky died at age seventy-eight on September 19, 1935, and has been given the following credits:

––The first individual who thoroughly analyzed the reaction function in relation to rockets launched to outer space, and use of the rocket within space/vacuum.

––Advanced the rocket equation for use with spaceflight.

––Produced groundbreaking mathematical calculations, such as proving a very high escape velocity was required for a vehicle to exit Earth’s atmosphere.

––Earned the title “Father of Cosmonautics” in Russia.

The Soviet Union mythologized Tsiolkovsky late in his life, then let his legacy slip upon his death for two decades. But with satellite launches in 1957 coinciding with the centennial of the distinguished scientist’s birth year, his life and achievements were once again celebrated.