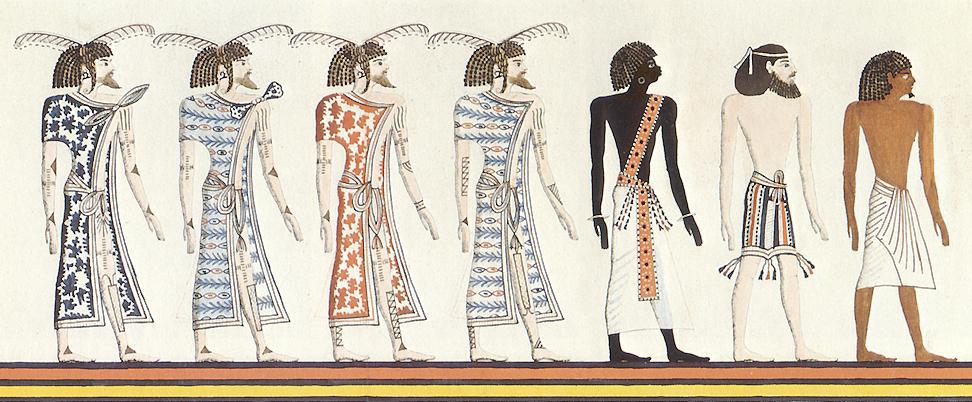

Modern Recreation of an Ancient Egyptian Relief Depicting the Races of Man Known to the Egyptians – From Right to Left: Egyptian, Canaanite/Asiatic, Nubian, and Four Different Libyan Chieftains

JERUSALEM THE GOLDEN

The separation of the two lands into their constituent parts might have been the new political reality, but it was anathema to traditional Egyptian ideology, which emphasized the unifying role of the king and cast division as the triumph of chaos. As the Hyksos had shown five centuries earlier, the sheer weight and antiquity of pharaonic beliefs had a tendency to win in the end. And, as the Libyan elite became more entrenched, more secure in its exercise of power, a curious thing happened. In certain important aspects, it started to go native.

It was at Thebes, heartland of pharaonic orthodoxy, that the first signs of a return to the old ways manifested themselves. After the “reign” of Pinedjem I (1063–1033), subsequent high priests eschewed royal titles, dating their monuments instead to the reigns of the kings at Djanet. Not that men such as Menkheperra, Nesbanebdjedet II, and Pinedjem II were any less authoritarian or ruthless than their predecessors, but they were willing to recognize the supreme authority of a single monarch. This was an important, if subtle, change in the prevailing philosophy. It reopened the possibility of political reunification at some point in the future.

That moment came in the middle of the tenth century. Near the close of the reign of Pasebakhaenniut II (960–950), control of Thebes had been delegated to a charismatic and ambitious Libyan chieftain from Bast, a man named Shoshenq. As “great chief of chiefs,” he seems to have been the most forceful personality in court circles. Moreover, by marrying his son to Pasebakhaenniut’s eldest daughter, Shoshenq reinforced his connections with the royal family. His calculations paid off. After Pasebakhaenniut’s death, Shoshenq was ideally placed to take the throne. The chieftain’s accession marked not just the beginning of a new dynasty (reckoned as the Twenty-second), but the start of a new era.

From the outset, Shoshenq I (945–925) moved to centralize power, reestablish the king’s political authority, and return Egypt to a traditional (New Kingdom) form of government. In a break with recent practice, oracles were no longer used as a regular instrument of government policy. The king’s word had always been the law, and Shoshenq felt perfectly able to make up his own mind without Amun’s help. Only in far-off Nubia, in the great temple of Amun-Ra at Napata, did the institution of the divine oracle survive in its fullest form (with long-term consequences for the history of the Nile Valley).

Despite his overtly Libyan name and background, Shoshenq I was still the unchallenged ruler of all Egypt. Moreover, he had a practical method of imposing his will over the traditionally minded south, and reining in the recent tendency toward Theban independence. By appointing his own son as high priest of Amun and army commander, he ensured Upper Egypt’s absolute loyalty. Other members of the royal family and supporters of the dynasty were similarly appointed to important posts throughout the country, and local bigwigs were encouraged to marry into the royal house to cement their loyalty. When the third prophet of Amun married Shoshenq’s daughter, the king knew he had the Theban priesthood well and truly in his pocket. It was just like the old days.

To demonstrate his newfound supremacy, Shoshenq consulted the archives and turned his attention to the activities traditionally expected of an Egyptian king. He ordered quarries to be reopened and sat down with his architects to plan ambitious building projects. While ordering further removals of New Kingdom pharaohs from their tombs in the Valley of the Kings, he nonetheless took pains to portray himself as a pious ruler and actively sought opportunities to make benefactions to Egypt’s great temples. For the first time in more than a century, fine reliefs were carved on temple walls to record the monarch’s achievements—even if the monarch in question was unashamed of his Libyan ancestry. But for all the piety and propaganda, the art and architecture, Shoshenq knew that there was still one element missing. In days of yore, no pharaoh worthy of the title would have sat idly by as Egypt’s power and influence declined on the world stage. All the great rulers of the New Kingdom had been warrior kings, ready at a moment’s notice to defend Egypt’s interests and extend its borders. It was time for such action again. Time to reawaken the country’s long-dormant imperialist foreign policy. Time to show the rest of the Near East that Egypt was still in the game.

A border incident in 925 provided the perfect excuse. With a mighty army of Libyan warriors, supplemented—in time-honored fashion—by Nubian mercenaries, Shoshenq marched out from his delta capital to reassert Egyptian authority. According to the biblical sources,1 there was murky power politics at play, too, with Egypt stirring up trouble among the Near Eastern powers and acquiescing in, if not actively encouraging, the breakup of Solomon’s once mighty kingdom of Israel into two mutually hostile territories. Whatever the precise context, after crushing the Semitic tribesmen who had infiltrated Egypt in the area of the Bitter Lakes, Shoshenq’s forces headed straight for Gaza, the traditional staging post for campaigns against the wider Near East. Having captured the city, the king divided his army into four divisions (with distant echoes of Ramesses II’s four divisions at Kadesh). He sent one strike force southeast into the Negev Desert to seize the strategically important fortress of Sharuhen. Another column headed due east toward the settlements of Beersheba and Arad, while a third contingent swept northeast toward Hebron and the fortified hill towns of Judah. The main army, led by the king himself, continued north along the coast road before turning inland to attack Judah from the north.

According to the biblical chroniclers, Shoshenq “took the fortified cities of Judah and came as far as Jerusalem.” Curiously, the Judaean capital is conspicuously absent from the roll call of conquests that Shoshenq had carved on the walls of Ipetsut to commemorate his campaign, but it is possible that he accepted its protection money without storming the walls. The city’s lament—that “he took away the treasures of the house of the Lord and the treasures of the king’s house; he took away everything”3—may indeed be a true reflection of events.

With Judah thoroughly subjugated, the Egyptian army continued its devastating progress through the Near East. Next in its sights was the rump kingdom of Israel, with its new capital at Shechem—the site of a famous victory by Senusret III nearly a millennium earlier. Other localities, too, echoed down the centuries as the Egyptians took Beth-Shan (one of Ramesses II’s strategic bases), Taanach, and finally Megiddo, scene of Thutmose III’s great victory of 1458. Determined to secure his place in history and prove himself the equal of the great Eighteenth Dynasty warrior pharaohs, Shoshenq ordered a commemorative inscription to be erected inside the fortress of Megiddo. Having thus secured an overwhelming victory, he led his army southward again, via Aruna and Yehem to Gaza, the border crossing at Raphia (modern Rafah), the Ways of Horus, and home. Once safely back in Egypt, Shoshenq fulfilled the expectations of tradition by commissioning a mighty new extension to the temple at Ipetsut, its monumental gateway decorated with scenes of his military triumph. The king is shown smiting his Asiatic enemies while the supreme god Amun and the personification of victorious Thebes look on approvingly.

Yet if all this sword-wielding and flag-waving was supposed to usher in a new era of pharaonic power, Egypt was to be sorely disappointed. Before the work at Ipetsut could be completed, Shoshenq I died suddenly. Without its royal patron, the project was abandoned and the workmen’s chisels fell silent. Worse, Shoshenq’s successors displayed a lamentable poverty of aspiration. They reverted all too easily to the previous model of laissez-faire government and were content with limited political and geographical horizons. Egypt’s temporary renaissance on the world stage had been a false dawn. The country’s renewed authority in the Near East withered away just as quickly as it had been established. And, far from being overawed by Shoshenq I’s brief display of royal authority, Thebes became increasingly frustrated at rule from the delta.

The specter of disunity stalked the city’s streets once more.

TROUBLE AND STRIFE

Shoshenq i’s policy of putting his own son in control of Thebes had succeeded in its objective of bringing the south under the control of the central government. This achievement, as much as Shoshenq’s drive and determination, had made his Palestinian campaign possible. It gave the king the ability to levy troops and supplies from the whole of Egypt, and to recruit mercenaries from Nubia. But the ethnic tensions between the largely Egyptian population of Upper Egypt and the country’s Libyan rulers were never far below the surface, and the capital city of Djanet was a world away from Thebes, both culturally and geographically. It was only a matter of time before southern resentment boiled over.

The king who tempted fate too far was Shoshenq I’s great-grandson, Osorkon II (874–835). During his long reign, he lavished attention on his ancestral home, Bast, especially its principal temple dedicated to the cat goddess Bastet. Most impressive of all his commissions was a festival hall to celebrate his first thirty years on the throne. The hall stood at the temple entrance and was decorated with scenes of the jubilee ceremonies, many of them harking back to the dawn of Egyptian history. In conception, it was every inch a traditional pharaonic monument. In execution, too, it stood comparison with the grand edifices of the New Kingdom. But its location—the remote central delta, not the religious capital of Thebes—betrayed its patron’s provincial origins. Osorkon II further underlined his loyalty to his home city by building a new temple in Bast, dedicated to Bastet’s son, the lion-headed god Mahes. Yet, far from lionizing their sovereign for such pious works, the Thebans looked on in disgust.

Eventually, Upper Egyptian frustration reached the breaking point. The inhabitants of Thebes desperately wanted self-rule and looked for a figurehead to lead the charge. The spotlight, not unnaturally, fell upon the high priest of Amun, Horsiese. The fact that he was Osorkon II’s second cousin mattered less than the symbolic potency of his office. As head of the Amun priesthood, Horsiese represented the economic and political strength of Ipetsut and of Upper Egypt in general. So, in the middle of Osorkon II’s reign, Horsiese bowed to local opinion and duly proclaimed himself king in Thebes. Two centuries earlier, other high priests had similarly claimed kingly titles and ruled the south as a counterdynasty, separate from the main royal line in the delta but connected to it by family ties. Horsiese and his backers had obviously studied their history.

The declaration of independence by Thebes marked the end of Shoshenq I’s united realm, the end of his superpower dream, and a return to the fractured state of the post-Ramesside era. But the current sovereign, Osorkon II, seemed not to mind. For him, the devolution of power to the provinces was an honorable tradition, one that could be safely accommodated within the tribal system of alliances that was his inheritance from his nomadic forebears. He could tolerate breakaway rulers, as long as they were relatives. Keeping it in the family was the Libyan way.

In fact, Horsiese’s independent reign was a short-lived affair. Relations with the delta continued much as before, and any notion of real Theban independence was illusory. But the Amun priesthood, having savored the sweet taste of self-determination, had no appetite for a return to centralized control. The principle of southern autonomy had been reestablished, apparently with the tacit approval of the main royal line. The genie was out of the bottle. Henceforth, temple and crown would go their separate ways, with profound consequences for Egyptian civilization.

In 838, the new high priest of Amun, Osorkon II’s own grandson Takelot, picked up where his predecessor had left off, proclaiming himself king (as Takelot II) and establishing a formal counterdynasty at Thebes. Osorkon died just three years later, reconciled, it seems, to the explicit division of his realm and the diminution of his royal status. On his grave goods, he had himself shown undergoing the Weighing of the Heart, to decide if he was good enough to win resurrection with Osiris in the underworld. In the past, kings had enjoyed (or presumed) an automatic passport to the afterlife; only mortals had had to face the last judgment. Osorkon was not so sure on which side of the line he stood. In a gesture of farewell, the dead king’s faithful army commander carved a lament at the entrance to the royal tomb, but it was a threnody for a fellow traveler, not an elegy for a divine monarch. Within six years of Osorkon II’s death, even sporadic recognition of the northern dynasty ceased at Thebes, all monuments and official documents being dated to the years of Takelot II’s independent reign (838–812). The whole of Upper Egypt, from the fortress of Tawedjay to the first cataract, recognized the Theban king as its monarch. The future of the south now belonged to Takelot and his heirs.

But not everyone in Thebes rejoiced at this turn of events. Takelot and his family had their detractors, and their effective monopoly of the Amun priesthood’s great wealth caused serious resentment, not least among jealous relatives who harbored ambitions of their own. If the Libyan feudal system allowed for regional autonomy, it also encouraged vicious squabbles between different branches of the extended royal clan. Just a decade into Takelot II’s rule, one of his distant relations, a man by the name of Padibastet (perhaps a son of Horsiese’s), decided to chance his arm. In 827, with tacit support from the northern king, he proclaimed himself ruler of Thebes, in direct opposition to Takelot. There were now two rivals for the southern crown. For a dyed-in-the-wool Libyan such as Takelot, there was only one solution to the crisis—military action. From the safety of his fortified headquarters at Tawedjay—which was named, with characteristic lack of understatement, the “crag of Amun, great of roaring”—he dispatched his son and heir, Prince Osorkon, to sail south to Thebes with an armed escort to oust the pretender and reclaim his birthright.

Force won the day, and “what had been destroyed in every city in Upper Egypt was reestablished. Suppressed were the enemies … of this land, which had fallen into turmoil.” On reaching Thebes, Prince Osorkon took part in a religious procession to confirm his pious credentials before receiving homage from the entire priesthood of Amun and every district governor. Nervously, they all made a public declaration, swearing that the prince was “the valiant protector of all the gods,” chosen by Amun “amongst hundreds of thousands in order to carry out what his heart desires.” And well they might, knowing as they did the alternative. Once back in control, Prince Osorkon showed the rebels (some of whom were his own officials) no mercy. In his victory inscription, he callously describes how they were bound in fetters, paraded before him, then carried off “like goats the night of the feast of the Evening Sacrifice.”6 As a brutal warning to others, “Every one was burned with fire in the place of the crime.”

With his enemies literally reduced to ashes, Prince Osorkon set about putting Theban affairs in order. He confirmed the temple revenues, heard petitions, presided at the inauguration of minor officials, and issued a flurry of new decrees. And all this administrative activity came with an admonition:

As for the one who will upset this command which I have issued, he shall be subject to the ferocity of Amun-Ra, the flame of Mut shall overcome him when she rages, and his son shall not succeed him.

To this he added, modestly, “whereas my name will stand firm and endure throughout the length of eternity.” The stones of Ipetsut must have echoed back their approbation: after all the vicissitudes of recent history, here was a prince in the old mold.

The following year, Prince Osorkon visited Thebes on no fewer than three occasions, to take part in major festivals and present offerings to the gods. He had evidently calculated that more frequent public appearances might win over the doubters and prevent further trouble. He was sorely mistaken. Far from cowing the dissenters, his harsh treatment of the rebels had merely stoked further resentment and hatred among the priesthood. A second, full-scale rebellion broke out in 823, once again with Padibastet as its figurehead. The “great convulsion” precipitated outright civil strife, with families and colleagues divided between the two factions. This time around, Padibastet was the winner, thanks to support from senior Theban officials. He moved quickly to consolidate his position, appointing his own men to important offices. Thebes was lost to Prince Osorkon and his father, Takelot II. They retreated to their northern stronghold to lick their wounds and bemoan their fate. “Years elapsed in which one preyed upon his fellow unimpeded.”

But if recent events had shown anything, it was that Theban priests were fickle friends. Another decade later, and Prince Osorkon was back in Thebes, restored as high priest of Amun to the groveling acclamation of his followers: “We shall be happy on account of you, you having no enemies, they being non-existent.” It was, of course, all hot air. Padibastet had not gone away, and the death soon afterward of Prince Osorkon’s father, Takelot II, merely strengthened the rival faction. A third rebellion in 810 saw Padibastet seize control of Thebes once more, but by 806, Prince Osorkon was back in town and presenting lavish offerings to the gods. A year later, Padibastet had the upper hand again. The prince’s faction could not so easily bounce back from this latest setback, and Osorkon once again retreated to the “crag of Amun” to ponder his next move.

Finally, Padibastet’s death in 802 shuffled the pack anew, and his successor showed none of the same determination. So, in 796, nearly a decade after his latest expulsion, Prince Osorkon sailed again for Thebes. This time, he took no chances. His brother, General Bakenptah , was commander of the fortress of Herakleopolis, and hence was able to call upon a significant military contingent. Together, the two brothers stormed the city of Amun and “overthrew everyone who had fought against them.”

After a power struggle lasting three decades, Prince Osorkon was finally able to claim the kingship of Thebes uncontested. For the next eighty years, under him and his successors, the destiny of Thebes and Upper Egypt did indeed lie with the descendants of Takelot II, just as the old king had hoped. The family’s public devotion to Amun of Ipetsut had paid off. However, far to the south of Egypt, in distant upper Nubia, another family of rulers, even more devout in their adherence to the cult of Amun, had been watching the turmoil in Thebes with increasing alarm. In their minds, true believers would never stand for such discord in the supreme god’s sacred city. And so they came to a stark conclusion: only one course of action would cleanse Egypt of its impiousness. It was time for a holy war.