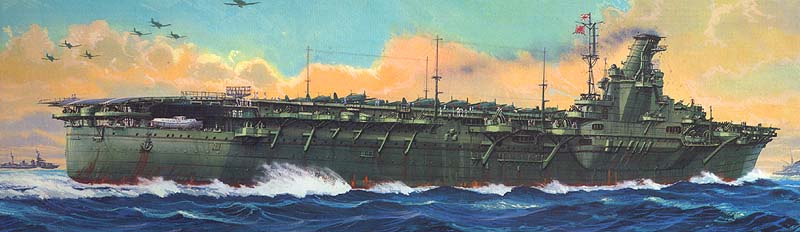

IJN Junyo

IJN Shokaku

Movement of opposing forces, 16—17 June 1944.

Movement of opposing forces, 18 June 1944.

On the morning of 11 June Admiral Ozawa received the first reports of TF 58’s strikes on the Marianas. At first he thought these raids were nothing more than diversionary attacks meant to take the heat off the Biak landings. The next day, however, brought more detailed reports about the American forces attacking the islands.

Japanese reconnaissance planes had snooped TF 58 and had estimated the composition and position of the attacking forces as: two carriers, one light carrier, and one battleship ninety miles east of Saipan; two more carriers ninety miles northeast of Saipan; a third group of two carriers, two light carriers, and three battleships ninety miles southeast of Saipan; and a final group of five carriers at an unreported position.

These reports painted an accurate picture of the disposition of the American forces, and Ozawa now knew that TF 58 was out in force. However, until it could be clearly confirmed that the Marianas were actually the target of a full-scale invasion, Ozawa was limited in his actions. Biak was still a slim possibility for a fleet action, and Ozawa’s big battleships, the Yamato and Musashi, were tied down at Batjan for the KON Operation.

On the 13th the situation became clearer to the Japanese. American battleships were reported shelling Saipan. It was now obvious the island was to be the target for an amphibious landing. At 0900 on the 13th the Mobile Fleet weighed anchor and began to sortie from Tawi Tawi, bound for Guimaras anchorage between Panay and Negros. Actually this sortie was not a reaction to the U.S. incursion into the Marianas, as it had already been planned. The increasing attention U.S. submarines had been paying to the area—and the paucity of destroyers to combat them—along with the lack of airfields for the training of the green flight crews had made Tawi Tawi a poor spot for massing the Mobile Fleet. Therefore, on 8 June Ozawa decided to move his fleet to Guimaras, or even Manila. That same day the 2nd Supply Force, which had been sent to a position east of the Philippines on the 3rd, was ordered to Guimaras.

As the Mobile Fleet steamed out of Tawi Tawi on the 13th, it was picked up by the submarine Redfin. Commander M.H. “Cy” Austin, the sub’s skipper, attempted to close the advanced force—destroyers and a pair of heavy cruisers—but their maneuvers kept him out of range. Two hours after the first vessels left Tawi Tawi, the main body came steaming out. Again Austin was unable to get into an attack position, but he could observe the movements of the Japanese and was able to send a vital contact report at 2000 that night. Nimitz, Spruance, and Mitscher now knew that six carriers, four battleships, several cruisers, and a number of destroyers were on the move.

Ozawa began consolidating his forces on the 13th. At 1727 the order “Prepare for A-GO Decisive Operation” was sent. Five minutes later the KON Operation was “temporarily” suspended and the Yamato, Musashi, Myoko, Haguro, Noshiro, and five destroyers were told to rendezvous with the rest of the Mobile Fleet in the Philippine Sea. Both supply forces were put on a thirty-minute standby status, and the battleship Fuso began transferring most of her fuel to the oilers of the 1st Supply Force at Davao. This last step is an indication of how strapped the Japanese were for oil.

The sortie of the Mobile Fleet was cursed by misfortune from the start. Just after the fleet left Tawi Tawi an inexperienced pilot made a bad landing on the flagship Taiho and crashed into some parked aircraft. The ensuing fire destroyed two Zekes, two Judys, and two Jills. This accident was thought to be a bad omen; a bad beginning for this all-important battle.

A second mishap struck the Japanese one day later. The 1st Supply Force departed Davao late on the 13th bound for a refueling rendezvous in the Philippine Sea. Just after midnight on the 15th sailors on the destroyer Shiratsuyu thought they detected an enemy submarine and the destroyer began to maneuver radically. Unfortunately, one of her turns brought the Shiratsuyu close, too close, across the bow of the Seiyo Maru. The oiler sliced the fantail off the destroyer and the Shiratsuyu quickly went down. There was no time to set depth charges on “safe” and these exploded as the ship sank, killing many in the water. Over one hundred of her crew were lost.

Ozawa’s main force reached Guimaras at 1400 on the 14th and began fueling from the Genyo Maru and Azusa Maru. The fueling and resupply was quickly and efficiently done. Early the next morning Ozawa was ready to leave Guimaras.

Marines of the 2nd and 4th Divisions had waded ashore on Saipan at 0844 on the 15th against heavy opposition. At 0855 Admiral Toyoda sent Admiral Ozawa the following message: “On the morning of the 15th a strong enemy force began landing operations in the Saipan-Tinian area. The Combined Fleet will attack the enemy in the Marianas area and annihilate the invasion force. Activate A-GO Operation for decisive battle.”

Five minutes after this order Toyoda sent a further message; one that all Japanese knew by heart: “The rise and fall of Imperial Japan depends on this one battle. Every man shall do his utmost.” Thirty-nine years earlier, Admiral Togo had uttered these same words just before his fleet crushed the Russian Baltic Fleet at Tsushima.

With fueling completed, Ozawa led the Mobile Fleet from Guimaras at 0800 on the 15th. The force crossed the Visayan Sea and headed for San Bernardino Strait, between Samar and Luzon. Although neither man probably expected the Mobile Fleet to escape being spotted early on, Admirals Toyoda and Ozawa hoped that the sortie would be undetected until the Japanese were upon the Americans. Their hopes were not to be realized.

Filipino coastwatchers kept an eye on the Mobile Fleet as it moved into San Bernardino Strait. At 1100 one such watcher reported three carriers, two freighters, and sixteen other vessels. Seven and one-half hours later another coastwatcher reported three battleships, nine carriers, ten cruisers, eleven destroyers and two submarine chasers passing through the strait. (Unfortunately, it took two days for these reports to reach Spruance.) In the strait itself was a U.S. submarine, the Flying Fish. Lieutenant Commander Robert Risser had brought his submarine to the area for the very purpose of watching for the Mobile Fleet.

On the afternoon of the 15th the Flying Fish was submerged just inside the eastern entrance to the strait. At 1622 he saw the Japanese ships passing about eleven miles away. They were staying close to shore. Risser’s mouth watered as he counted the juicy targets—three carriers, three battleships, and the usual cruisers and destroyers. But his orders were to report first, attack later. Risser tried to stay with the enemy as best he could, but the submarine’s best submerged speed was no match for Ozawa’s ships. That evening Risser surfaced and sent his important contact report. His message would be the first received by Spruance showing that the Japanese were definitely approaching the Philippine Sea.

As Risser took the Flying Fish back to Brisbane low on fuel, a second U.S. submarine was watching another part of the Japanese forces. Lieutenant Commander Slade D. Cutter was bringing the Seahorse up from the Admiralties to cover Surigao Strait at the southern end of Leyte. At 1845 Cutter saw smoke on the horizon. The Seahorse was about two hundred miles east of Surigao Strait at the time.

Cutter immediately went to his best surface speed and started to close with the target. As the Seahorse drew nearer, Cutter was able to figure the course and speed of the enemy force. Then, when the Seahorse was 19,000 yards away, one of her motors cut out, and the sub’s speed dropped off to 14½ knots. The Japanese ships pulled away into the darkness.

Because of effective jamming by the Japanese, Cutter was unable to get off a contact report until 0300 on 16 June: “At 1330 GCT task force in position 10-11 North, 129-35 East. Base course 045, speed of advance 16.5. Sight contact at dusk disclosed plenty of battleships. Seahorse was astern and could not run around due speed restrictions caused by main motor brushes. Radar indicates six ships ranges 28 to 39,000 yards. Carriers and destroyers probably could not be detected at those ranges with our radar.”

Cutter had found the Yamato and Musashi racing north from Batjan.

Back off Saipan much had been happening the past few days. When TGs 58.1 and 58.4 had steamed north to attack the Bonins, the other two task groups had remained off Saipan to support the landings. Although most of the close support work was now being done by the “jeep” carriers of TG 52.14 (the Fanshaw Bay, Midway, White Plains, Kalinin Bay) and TG 52.11 (the Corregidor, Coral Sea, Gambier Bay, Nehenta Bay), the fast carriers were also kept busy.

Destroyers were fueled on the morning of the 14th while both groups sent strikes against all four of the major islands. Over four hundred sorties were launched during the day with few losses to the attackers. The two groups then retired to the west of Rota for the night.

15 June 1944, D-Day (or Dog Day, as it was known for this operation), was a beautiful day, but it is doubtful if many of those present were thinking how lovely it was. When the Marines stormed ashore in the morning they found that many targets had not been touched by the prelanding bombardment or the aerial strikes. Fighting was savage and losses heavy. By the 18th, though, the beachhead was secure and the Marines were there to stay.

Task Groups 58.2 and 58.3 were active on the 15th supporting the landings. Ninety-five sorties were sent over the beaches by TG 58.2 at H minus 90, followed by sixty-four Lexington and Enterprise planes at H-Hour. The two groups flew 579 target sorties. Only three planes and one pilot (all from TG 58.3) were lost during the day, but a number of others received varying degrees of damage from the still-heavy flak.

Around dusk Japanese planes began congregating near the American ships. The two U.S. groups were recovering planes about forty miles west of Saipan when the first group of enemy planes was detected. At 1800 a division of San Jacinto planes was vectored out to investigate a bogey at 20,500 feet. A “Nick” was found and quickly shot down. Ten minutes after the first vectors a second division was sent to investigate bogeys fifty-two miles away. At 1820 the San Jacinto planes contacted six “Tonys.” (Again misidentifications. These planes were probably Zekes or Jills.) In the ensuing combat at 22,000 feet, five of the enemy planes were destroyed and the last one damaged. One of the Fighting 51 pilots had stayed high with a malfunctioning engine when the other pilots jumped the enemy planes. He was in a good position to see two more Japanese planes—Hamps—diving on his friends below. Pushing over, he got on the tail of one Hamp and splashed it. The other plane fled.

A big attack sent in from Yap came shortly after the sun went down. Task Group 58.2 beat off an attack by a few planes with accurate antiaircraft fire, but the main attack was against the carriers of TG 58.3. A pair of Enterprise F4U-2N Corsair night fighters had been launched at 1845 and at 1905 were vectored toward some bogeys. The target was only five miles away. Lieutenant Commander Richard E. Harmer and his wingman, Lieutenant (jg) R.F. Holden, soon picked it up—eight of the new Frances bombers with four or five fighters as escorts.

Harmer attacked the formation from the side but could not see the results of his attack in the darkness. Then Holden warned him of a fighter on his tail. Tracers streaking past Harmer’s fighter confirmed this warning. As Harmer tried to evade the enemy fighter, 20-mm fire from one of the bombers hit his Corsair, shorting his formation lights “on.” Holden finally knocked the enemy plane off Harmer’s tail, the fighter corkscrewing down from 1,500 feet. Two more enemy planes attempted to get the Americans, but they were easily evaded. Harmer, unable to turn his lights off and feeling highly visible not only to the Japanese but to the gunners on the ships below, retired from the arena with Holden, and got out of the battle.

Now without any fighters to harass them, the Japanese circled the American ships (prudently out of antiaircraft gun range) and prepared to attack. The usual flares and float lights were dropped and then the Frans darted in. The North Carolina and Washington opened fire shortly after 1900, followed by the destroyers in the screen. At 1907 Princeton lookouts sighted seven planes low on the water dead ahead. But the Japanese fliers were not interested in the light carrier. They were after bigger game, the Lexington and Enterprise. The task group began to maneuver drastically while at the same time firing radar-directed 5-inch and 40-mm shells that engulfed the enemy planes.

Five planes made runs on the Lexington to no avail. Four were quickly slammed into the water. The other was stopped in mid-air by the wall of fire, and fell into the sea without burning. The enemy pilots were brave. One Frances almost hit the Lexington’s bridge before falling in flames off the starboard quarter. Another “streaked like a fire ball, close aboard to port, flaming so hotly he warmed the faces as well as the hearts of the gunners.” This pilot desperately tried to crash his doomed aircraft into the planes parked aft on the flight deck. He almost succeeded. His right engine suddenly stopped and he crashed only a few yards from the stern.

Torpedoes were slicing through the water now, and all the ships were heeling over to miss them. At one point Captain Burke had to lean over the wing of the Lexington’s bridge to see one torpedo flash past. The Enterprise had two “fish” miss her by less than fifty yards.

The surviving enemy planes scuttled out of the area and by 2230 all radar scopes were clear. Only thirteen of the attackers were able to return to Yap. Lexington gunners claimed five planes, while the Enterprise claimed two and the Princeton one. No ships were lost but there had been casualties. Three sailors were killed and fifty-eight wounded, when antiaircraft shells were accidentally fired into other ships. The casualties had been caused by those almost inevitable (and unavoidable) incidents that had happened before in the fury of battle and would happen again.

D plus 1, the 16th, was a day of decision, planning and fighting for the Americans. Fueling took up part of the day as TG 58.2 fueled from TG 50.17’s oilers in the morning and TG 58.3 did the same in the afternoon. The seemingly ever-present Copahee was again on hand to deliver replacement aircraft to some of the fast carriers and to receive their flyable “duds” in exchange.

The reports from the Flying Fish and Seahorse had finally reached Spruance and Mitscher, and they now knew the Japanese were coming out. The day before, Vice Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner (the Expeditionary Force commander) had recommended to Spruance that the landings on Guam be set for the 18th. (At this time it had seemed that the landings on Saipan were going fine, and there was as yet no firm word on the direction the Japanese Fleet was taking.)

When the reports of the Mobile Fleet’s sortie into the Philippine Sea were received, it became obvious that some major decisions and replanning were needed. On the morning of the 16th Spruance boarded Turner’s command ship, the Rocky Mount. In conference with Turner and Lieutenant General Holland M. Smith, USMC, overall commander of the troops ashore, Spruance made several critical decisions. It was decided to:

1.Land the 27th Division immediately. Since with this action there would be no reserve force, the Guam landings were cancelled and the Southern Attack Force was to stand by as a floating reserve.

2.Augment TF 58’s screen by detaching some cruisers and destroyers from fire support TGs 52.10 and 52.17.

3.Unload supplies and troops until dark of the 17th, after which the transports would be sent 200-300 miles east for safety.

4.Send the old battleships and screens of TGs 52.10 and 52.17 about twenty-five miles west of Saipan to cover the island in case the Japanese got around TF 58.

5.Use the jeep carriers exclusively for close air support.

The day before, Spruance had asked General MacArthur to have his Wakde- and Los Negros-based PB4YS stretch their searches to the limit, about 1,200 miles. The Liberators did not pick up anything, however. On the 14th Spruance had directed Vice Admiral John H. Hoover at Eniwetok to send a patrol-plane tender forward and to prepare a patrol squadron when ordered. Now Hoover was ordered to send six radar-equipped PBMs of VP-16 from Eniwetok to Saipan. The PBMs were to be used for long-range searches from Saipan.

Spruance returned to his flagship the Indianapolis and prepared to join TF 58. Because the reports from the Flying Fish and Seahorse seemed to indicate that two separate groups of enemy ships were out, Spruance felt the Japanese would probably be following their usual tactics of dividing their forces. This appreciation of the enemy’s intentions, perhaps influenced by the Z Plan translation in his hands, was to color Spruance’s decisions throughout the battle.

Some very good advice reached Spruance on the 16th. Admiral Nimitz, on the recommendation of Vice Admiral John H. Towers (Nimitz’s Deputy Commander-in-Chief), told Spruance and Mitscher to watch out for the possibility that the Japanese might try to keep their carriers out of range of TF 58’s aircraft, and instead shuttle their planes back and forth to Guam.

From earlier reconnaissance and intelligence reports the Americans had a pretty good idea of the composition of the Mobile Fleet. Admiral Reeves, TG 58.3’s commander, said in his operations plan: “Any resistance to the operation by way of surface engagement or carrier attack will probably be from part or all of the new Japanese First Striking Fleet. This fleet is thought to contain five fast battleships and possibly the Fuso as well. Carrier Divisions One, Two, and Three (nine CV and CVLs with a total complement of 255 VF, 177 VSB, 99 VT and 9 VSO) and about eleven heavy cruisers, 35 DDs are believed assigned to this fleet.”

Mitscher’s appraisal was pretty much the same: “For the first time in more than 18 months the enemy has a large carrier force in fighting condition. His 3 CVs, 2 XCVs, and 4 CVLs which are ready for combat carry planes equivalent in number to those carried by 4 Essex and 3 Independence class carriers. . . . If the enemy uses all his carrier-based planes in conjunction with the land planes based in the Marianas, he will still have fewer aircraft available for attacking our ships than we will be able to employ against him. Enemy task force action will give our own task forces a chance to close the enemy, bring his force into action, and perhaps score a crippling victory.”

Mitscher’s operation plan also considered three possible courses of action the Japanese could take if they sortied for battle: “(A) They could approach from the general direction of Davao under their air cover from the Philippines, Palau and Yap and strike the fleet from a southwesterly direction. (B) They could approach around northern Luzon and strike from a northwesterly direction. (C) They could approach easterly and strike from a position west of the Marianas.”

Mitscher and his staff thought (A) was most likely, though (C) was possible. The other possibility was considered very unlikely. While a southwest approach might be a diversion or a flanking route, Mitscher thought it not a “serious consideration so long as the major portion of the fleet could be engaged to the westward.” He also felt that as long as the new Japanese battleships (the Yamato and Musashi, in particular) were not in this attacking force, the old battleships, escort carriers, and screening vessels of the U.S support force could handle them.

On the morning of 16 June Mitscher informed his ships of the possibilities, saying, “Believe Japanese will approach from southerly direction under their shore-based air cover close to Yap and Ulithi to attempt to operate in vicinity of Guam. However, they may come from the west. Our searches must cover both possibilities. Will ask Harrill and Clark to search north and west of us tomorrow.” As related earlier, Clark’s and Harrill’s groups searched to the southwest of their position and found nothing. Clark’s imaginative plan to “trap” the Japanese was stillborn, and the two forces raced south to join the rest of TF 58.

Mitscher was taking no chances and ordered his planes to hit the airfields on Guam and Tinian in an attempt to neutralize them. A total of 332 sorties were flown during the day and most of them met heavy and accurate antiaircraft fire. Six planes were shot down, including one by friendly antiaircraft fire, but only one pilot and two crewmen were lost. One of the luckier pilots, who was not without a sense of adventure, was Ensign W.R. Mooney. This San Jacinto flier was hit by flak over Guam but was able to set his plane down in the water and climb into his raft. Though about fourteen miles offshore, Mooney paddled his raft to Guam where he scrambled ashore undetected by the enemy. At night he would hide in the undergrowth, and just before dawn he would take his raft back down to the shore and paddle out to sea, hoping some friendly search plane would spot him and bring rescue. Mooney followed this ritual for over two weeks before finally being picked up on 3 July.

Another pilot shot down on the 16th was Commander William R. “Killer” Kane, CO of Air Group 10. Kane was to be air coordinator for the first strikes of the day. As he and his wingman approached Saipan shortly before 0600, the sea below was still dark. Only a few ships could be seen. Nervously, both pilots rechecked their IFF transmitters.

Not wanting to fly over the invasion forces, Kane began a turn back to the west. Suddenly, a big burst of flak exploded under the left wing of his Hellcat. The plane pitched over violently and Kane’s goggles flew off his head. The Hellcat’s engine began smoking and Kane started thinking about bailing out. More bursts appeared nearby and tracers were weaving around the plane.

Kane opened his canopy and released his seat belt. As he prepared to go over the side, he discovered his fighter was not on fire and the engine was ticking over smoothly. He settled back into his seat—forgetting to refasten his seat belt—and led his wingman out of the antiaircraft fire. But as he tried to climb back to his original altitude, the black puffs cracked around the two planes again.

As Kane called angrily over the radio for the ships to knock off the shooting, he saw his oil pressure drop to zero. He decided to ditch near some transports. The antiaircraft fire followed him down but stopped as he put the Hellcat into the water. The big fighter skipped once, then dug its nose into the water. Without his seat belt fastened, Kane slammed forward against the gunsight. Groggy and with blood streaming from his head, Kane pulled himself out of his sinking plane and clambered into his raft. Before the destroyer Newcomb picked him up, Kane had a few choice words—and many ugly thoughts—about gunners who did not know aircraft recognition and sailors who could not read IFF signals. That afternoon, with a splitting headache, he was returned to the Enterprise.

Mitscher kept his planes pounding Guam and Tinian throughout the day, but as soon as the attackers departed, the Japanese rushed to work and quickly had the airfields back in service. Following a day of bombing, Tinian reported to Tokyo that the field was back in operation as of 1800.

Another disturbing observation was made by Commander Ernest M. Snowden, skipper of Air Group 16. During a strafing pass of the Ushi Point field on Tinian, Snowden noticed quite a few enemy planes parked around the field. Many appeared to be untouched by bullets or shrapnel. Although twenty-four planes were claimed destroyed on the ground and many others damaged, there were too many untouched planes left for comfort.