What nearly brought Poland and the Ottoman Empire into armed conflict in this period was not the deliberate policy of the King, the Sultan or the Pope, but the unpredictable actions of two mutually hostile powers: the Tatars and the Cossacks. The Crimean Tatars were at least nominally subject to the Sultan. Although the Tatar Khans collected their own taxes and minted their own coins, they did acknowledge a higher power in Istanbul; a new Khan would be elected in the Crimea from the ruling Giray dynasty, but the election would then be submitted to the Sultan for approval, and the Ottomans did sometimes depose an uncooperative Khan in order to put a more compliant one in his place. Because of their military and marauding activities, the Tatars acquired a grim reputation in Russia and Central Europe as savage Asiatic nomads. The English Ambassador in Istanbul in the 1580s solemnly reported that ‘theie are borne blynde, openinge theire eyes the thirde daye after; a thinge peculier to them onlye, a brutishe people, open vnder the ayer lyvinge in cartes covered wth oxe hides’; all the adult men, he said, were ‘theeves and Robbers’. While it is true that Tatar herdsmen did travel in carts with their flocks during the summer months, at the core of the Tatars’ territory was a settled society, with agricultural estates (worked mostly by slaves they had captured). Their ruling family and nobility contained educated men: Gazi Giray II, who was installed by the Sultan in 1588, was a poet with a good knowledge of Arabic and Persian, and the Khans’ palace contained a well-stocked library. But Tatar light cavalry (typically, a force of 20–30,000 men when led by the Khan) was a much feared auxiliary element in the Ottomans’ European campaigns, and at other times large bands of Tatars would go raiding in Polish and Russian territory for slaves and other booty.

Opposing them in the south-eastern part of the Polish state was an official defence force of roughly 3,000 men, stretched out over an area more than 600 miles across. Its efforts, very inadequate in themselves, were supplemented by those of a much more informal fighting population, the Zaporozhian Cossacks, who were based in the marshy territory of the lower Dnieper river, south-east of Kiev (‘Zaporozhian’ is from a word meaning ‘below the rapids’). Like their equivalents on the southern Russian steppes, the Don Cossacks, these people developed enough of a socio-political system to form at least a loose military organization, but not enough to become a state-like entity. They enjoyed the protection and sponsorship of some powerful landowners in the region, and in normal circumstances were willing to cooperate in a broad defensive strategy with the official forces of the Crown. But their ‘pursuits’ of Tatar raiders could often turn into raiding expeditions of their own, openly supported by local lords and administrators who took their share of the booty. Twentieth-century attempts to portray them as fighting either against feudalism or for national liberation are unconvincing; raiding was primarily an economic activity, and all classes could have an interest in it. The Tatar bands not only paid a tax on their booty to the Khan, but also, in some cases, had merchant investors who would give them horses on credit in return for half of the spoils. On the Polish side, Crown soldiers would sometimes provoke raids by the Tatars and then take care to intercept them only on their way home, when they were laden with goods (which could then be appropriated, or returned to the original owners for a fee). But the larger Cossack expeditions could also have a political dimension, whether by design, as their local protectors flexed their muscles vis-à-vis the Polish government, or by unintended consequence.

To the modern eye, such raiding, even on a large scale, seems like a regrettable and peripheral phenomenon, something to be understood as a transgression of the normal system, not a component of it. Yet if one looks at all the frontier zones between Christendom and the Ottoman world in this period, from the Dnieper marshes in the north to the maritime quasi-frontier of the Mediterranean in the south, one begins to see that it was very much part of the system. On both sides of the lengthy Ottoman–Habsburg border, local auxiliary forces grew up for which raiding was a constant feature of military and economic life. In the north-eastern corner of the Adriatic a small but highly active population of ‘Uskoks’, Slavic refugees and adventurers who theoretically acted as frontier troops for the Habsburgs, caused real harm to Ottoman trading interests – and much damage to Venetian–Ottoman relations – by their corsairing and piracy. The corsairs of the Albanian coast, based first in Vlorë and Durrës and later also in Ulcinj, preyed on much Christian shipping. And in the Mediterranean, the corsairs of North Africa were pitted against another group for which raiding was a central activity, the Knights of Malta. In all these cases, booty was either essential to the economy or (in the case of Malta) a vital motive for offensive action; this in itself implied that these societies were enmeshed in a larger pattern of economic interests, as they often depended on merchants coming from elsewhere to buy the goods they had seized. Of course, organized predation of this kind was not just a border phenomenon. Communities based at least partly on raiding, or on raiding combined with a sort of protection racket, could operate against domestic targets as well as foreign ones; in the northern Albanian mountains, a group of clans led by the warlike Kelmendi developed such a practice, and other bellicose populations such as the Himariots and the Maniots may at times have been fairly indiscriminate in their choice of prey. But the advantage of a frontier was that it provided a ready-made legitimation for all activities of this kind, so long as they were conducted against the other side; and even more legitimation was available when that frontier lay between two religions.

A whole range of these raiding societies thus existed, from states and state-like entities (Algiers, Tunis, Tripoli, Malta, the Crimean Tatar Khanate) to broad regional forces (the Cossacks, the ‘Grenzer’ communities of the Habsburg borders and their Ottoman counterparts) and small corsairing groups such as the Uskoks of Senj and their Albanian rough equivalents. Contemporaries sensed some of the similarities between them; for instance, the German writer on Ottoman affairs Johannes Leunclavius remarked that the Cossacks resembled both the Uskoks and the Morlachs (the Vlach and Slav fighters used on both sides of the Habsburg–Ottoman frontier), and Ottomans described the Tatars and the North African corsairs as the Sultan’s two ‘wings’. Modern historians seldom consider all these raiding entities together, perhaps because they do not fit the standard model of international history, based on the direct interactions of unit states, which the present naturally projects onto the past. Nevertheless, they should be regarded as an important element in the picture; one might think of them as the ‘irregular powers’, conjoined in a complex system of inter-power relations with the regular ones. Often they caused serious trouble not only to their enemies but also to their sponsors. Why did the latter tolerate them? Some parts of the answer are clear: they provided a relatively cheap form of permanent frontier defence; they became valuable auxiliaries in wartime; in peacetime their raiding activities honed the martial skills of large numbers of men; their constant probing of the enemy (or potential enemy) revealed points of weakness, while being covered by a degree of ‘deniability’; and up to a certain point, the harm they caused by their offensive actions could be useful, as the other side might offer concessions of various kinds in order to have them called off. All these points are valid, but to list them like this risks giving the impression that the irregular powers functioned as mere instruments, the tools of their sponsors’ regular power-politics. And that would be to ignore the fact that they often had interests and policies of their own, to which their protector-powers were sometimes forced, with great reluctance, to adapt.

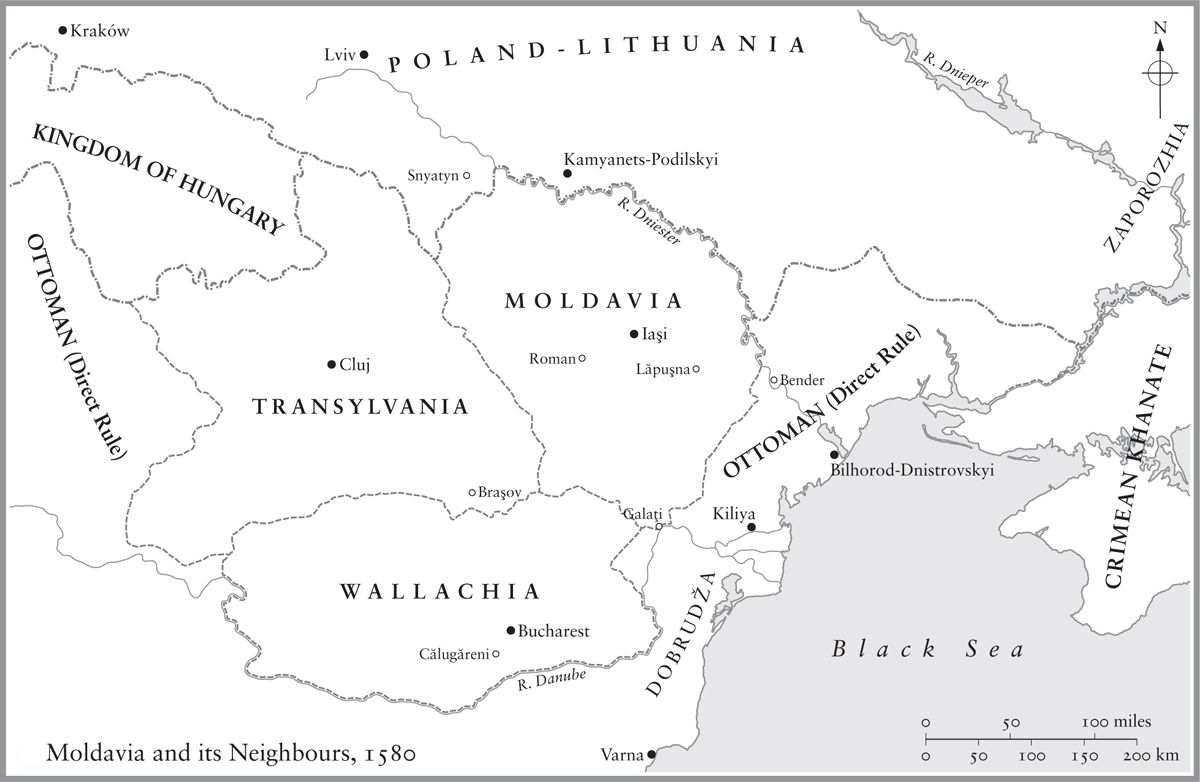

The activities of the Tatars and Cossacks bedevilled relations between Poland and the Ottoman Empire, and sometimes carried war and rebellion into the heart of the Moldavian state. In 1575 and again in 1577, Polish territory underwent large Tatar raids, in retaliation for Cossack attacks. The Voivod of Moldavia at this time was Petru Şchiopul, the Wallachian prince who had been imposed by the Sultan in 1574 in place of the rebellious Ioan cel Cumplit. A man claiming to be Ioan’s brother, known as Ioan Potcoavă (‘John Horseshoe’ – he broke them with his bare hands), raised a Cossack army and invaded Moldavia, seizing the capital, Iaşi, in late 1577; he then withdrew to Polish territory, where the authorities arrested and executed him, but in the following year two more Cossack invasions took place under other leaders. During 1578 the Sultan warned Stephen Báthory that if the Cossacks were not restrained, he would invade Poland. Stephen’s attempt to meet this challenge by setting up a small official Cossack army and giving it strict instructions not to attack Moldavia or any Ottoman territory was largely symbolic; it staved off the threatened invasion, but it did not give him real control of these warriors. In late 1579 a local Polish grandee organized a Cossack attack on the Ottoman fortress of Akkerman (Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi). This formed the immediate context of the Sultan’s decision to replace Petru Şchiopul; for Petru was regarded as pro-Polish, and therefore not the right person to develop a more hard-line policy against the Poles. Also, because he was a foreigner from Wallachia, Moldavian boyars had petitioned at Istanbul for him to be replaced by Iancu Sasul; those boyars represented, in effect, an anti-Polish party, and granting their wishes would strengthen their position. So it was that political circumstances, as well as the large payments organized by Bartolomeo Bruti, brought Iancu to the throne.

Iancu was generally believed to be an illegitimate son of Petru Rareş, the voivod who had been driven out by Süleyman the Magnificent in 1538 (but later reinstated); and he was called ‘Sasul’, ‘the German’, because his mother was the wife of a German leather-worker in the city of Braşov. Since the administrative records of the Moldavian government have not survived from this period, it is impossible to give any detailed and objective account of his rule. Instead, the picture is dominated by the later narrative of the Moldavian chronicler Grigore Ureche, who, writing in the 1640s, had nothing good to say about Iancu Sasul. According to Ureche, he introduced an unheard-of tithe of all cattle in the country, and this provoked a major revolt in the eastern province of Lăpuşna, which was crushed by the Moldavian army. Iancu was an evil man who ‘did not love the Christian religion’; he raped the wives of boyars, and several leading nobles consequently fled into exile. This account seems rather simplistic. We know that Iancu performed some routine acts of religious piety, donating numbers of Gypsy labourers, for example, to Orthodox monasteries – though the fact (if it is one) that he converted to Catholicism before his death may have tainted him in Moldavian eyes. It is indeed true that some leading nobles and ecclesiastics fled to Poland, but their reasons may have been primarily political, as they represented a pro-Polish lobby to which Iancu was opposed. He had a different policy which would, however, have pleased the Ottomans even less, had they known about it: from the start he was secretly in touch with the Habsburgs through their military commander in Upper Hungary. Towards the end of his rather brief rule in Moldavia he was apparently trying to acquire an estate in Habsburg territory, seeing it as a bolthole in which to evade another round of internal exile in the Ottoman Empire; but there may have been a larger strategic aspect to his cultivating these connections. When the Poles found out about them, in 1582, they were quick to inform Istanbul.

Stephen Báthory lobbied hard to get Iancu deposed; in the summer of 1582, when he despatched an envoy to a grand festivity in Istanbul celebrating the circumcision of the Sultan’s son, he sent with him, as a present to the Sultan, two captive Tatar princes. This magnanimous gesture, plus a large under-the-counter payment to Sinan Pasha, had the desired effect. Later that summer, when news reached Iancu that he was about to be recalled, the Voivod gathered all the cash reserves of the Moldavian treasury and headed for his Habsburg refuge. Unfortunately his route had to pass first through Poland. He was arrested there, and, after a brief detention, executed on the King’s orders in late September, before the Ottoman çavuş could arrive to take him back to Istanbul. Stephen Báthory offered various justifications for this: Iancu had opened his letters to the Sultan when Polish couriers had passed through Moldavia, and had added spurious passages to them; he had burnt down villages in Polish territory; and Poles who had sought justice from him had been beaten and imprisoned. (The papal nuncio in Poland also wrote, perhaps just repeating a standard line, that Iancu had made himself ‘utterly hateful’ to his people by violating their women.) Stephen did not mention the huge quantity of cash – between 400,000 and a million ducats, as rumour had it – which he expropriated. Nor did the Sultan make much fuss about that; a resetting of Ottoman–Polish relations had just taken place, and it was a sign of the Ottoman willingness to be conciliatory that the new Voivod of Moldavia was, once again, Petru Şchiopul.

Not much is known about Bartolomeo Bruti’s life in Moldavia during these years. As we have seen, a French ambassadorial despatch stated in 1580 that he was granted a boyar’s estate and an income of 3,000 ducats from the customs dues of a port – which was presumably Galaţi, the only significant port left to Moldavia, on the northern bank of the Danube. That despatch’s statement that he was also made general of the army might seem implausible, in view of Bartolomeo’s total lack of military experience; yet in January 1582 he was indeed joint commander of the Moldavian army, with the boyar Condrea Bucium, when it fought a major battle to crush the rebels of Lăpuşna. Bartolomeo had the official position of ‘postelnic’, meaning seneschal or court chamberlain, while Bucium was the grand ‘vornic’ or count palatine of Lower Moldavia; neither was ‘hatman’ (general of the armed forces), but it seems that Bartolomeo was in effect the senior minister for external affairs, and Bucium for internal ones. As the Postelnic, Bartolomeo also held the prefecture of Iaşi, the capital city, and judged its citizens. These honours – which depended above all on the fact that he was Iancu’s personal link to Sinan Pasha – represented an extraordinary transformation in his fortunes, from the ill-paid trainee dragoman and neglected underground agent of the previous years.

Bartolomeo must have found his new conditions strange as well as exhilarating. He was now in an overwhelmingly Eastern Orthodox country, and its language, Romanian, would have taken some time to learn, even though his knowledge of Italian gave him a good head-start. This was a very traditional society, a far cry from the Venetianized city communities of the Adriatic that were familiar to him, with their statutes and municipal rights; the Moldavian towns and their surrounding villages were regarded as the personal property of the voivod, and the laws were customary and unwritten. Whilst the dress of the voivod and his courtiers was partly Ottoman in style, with richly decorated cloaks like caftans, the hierarchy and ceremonies derived from the Byzantine tradition. In 1574 a French traveller, commenting on court life in Iaşi, wrote that ‘they honour their voivods like God, and drink excessively’ – though a few years later Stefan Gerlach assured a friend that the Moldavians were at least more civilized than the Wallachians. In the late 1580s a Jesuit would write about Moldavia that ‘literary writing is not held in esteem there, nor is it taught’; but he added that ‘the people are excellent and talented, and shrewd rather than simple.’ The population was quite mixed, especially in the towns; the merchant community included, as we have seen, both Armenians and Greeks (some of whom, especially those from Chios, were Roman Catholic), and Ragusans were active as tax- and customs-farmers. There were Protestant Germans, Hungarians and Hussites; and although the Jews had been expelled in 1579 at the insistence of Christian merchants, some seem to have returned under Iancu Sasul. There were also Albanians – villagers, traders and others. In 1584 the Jesuit Antonio Possevino would report from Poland that ‘the Voivod of Moldavia’s guard consists of 400 Trabants [a Central European word for bodyguard], who are Hungarian, and 50 Albanian and Greek halbardiers, who live like Muslims.’ So Bartolomeo Bruti would have found some people to talk to in his native tongue. But in any case he was not leading a solitary life. In these early years, at least, his wife Maria was with him. They had a son, probably within less than a year of their arrival in Moldavia, and had him baptized in Kamyanets-Podilskyi, the nearest town with a Catholic bishop. The boy was christened Antonio Stanislao – the first name honouring Bartolomeo’s father, and the second presumably paying respect to an influential Polish godfather.

In 1582 Bartolomeo Bruti went to Istanbul as the Voivod’s envoy to attend the festivities for the circumcision of the future Mehmed III. Public celebrations of such events, and of the accessions of new sultans, were not uncommon, but this was the most elaborate and extravagant that had ever been seen, lasting more than 50 days from early June to late July; half a million akçes (more than 8,000 ducats) had been set aside for staging it, invitations were sent to rulers in such distant places as Morocco and Uzbekistan, and the preparations took several months. It is not hard to guess the underlying reason for a jamboree which entertained much of the population of Istanbul. The Persian war, begun in 1578, was proving intractable, costly and increasingly unpopular; a large and distracting boost to morale, including displays of deference by foreign powers, was greatly to be desired. Certainly, nothing larger or more distracting could have been imagined. In the early stages of the festivities, senior pashas and the ambassadors of Muslim and Christian rulers presented lavish gifts. For the viziers and beylerbeyis, this was the most demanding instance of the whole Ottoman cult of gift-giving. Sinan Pasha presented the Sultan with fine horses, large quantities of luxury cloth, a gold-illuminated Koran and a golden bowl encrusted with rubies and turquoises, while giving the Sultan’s son a bejewelled golden sword, six male slaves, three horses and four illuminated books. The gifts of some foreign states were barely as lavish as that. The King of Poland sent quantities of highly prized Russian sable fur; the Venetian envoy, Giacomo Soranzo, brought 8,000 ducats’ worth of gold, silver and silk; and Iancu Sasul’s presents consisted of a silver fountain and other pieces of silverwork, to the value of 3,000 ducats.

The celebrations were held in the Hippodrome, which had been specially fitted up for the occasion, with a three-storey wooden stand for distinguished guests. Christians, such as the Ragusan envoys and Bartolomeo, were placed in the bottom storey. For the first few weeks the formal present-givings were interspersed with entertainments, involving athletes, fighting animals (the fight between a boar and three lions was almost won by the boar), rope-dancers, musicians and others; one jaded French observer, Jean Palerne, found the music ‘tuneful enough to make donkeys dance’. Sugar animals were paraded, including life-sized elephants and camels, and in the evenings the crowds were given free food and lavish firework displays. Then there were military performances (put on, Palerne noted, by Sinan, who wanted ‘to be recognized as a great warlord’), with realistic-seeming battles involving mock-castles; the Christian castles, which were triumphantly overrun, had squealing pigs inside them. In the second week of June the processions of the Istanbul guilds began, with elaborate displays, sometimes on large carriages or floats, demonstrating or symbolizing their work. More than 200 guilds took part, including nailsmiths, bucket-sellers, javelin-makers, pickle-sellers, caftan-makers, silk-spinners, tart-bakers and snake-charmers. On the helva-makers’ carriage a man made helva in a huge cauldron; on the barbers’, a barber shaved customers while standing on his head; the Jewish gunpowder-makers’ float had a powder-mill, and a man constantly igniting little explosions of powder against his bare skin. (The helva-makers also amused the crowd by trying to blow up a live rabbit with fireworks.) The mirror-makers dressed in clothes made out of pieces of mirror, while the manufacturers of coloured paper had 130 apprentices dressed in coloured paper. When they reached the Sultan the guildsmen gave him their own presents, both symbolic (giant shoes, paper tulips as tall as trees) and real: the guild of bird-catching pedlars solemnly presented two vultures, ten partridges and 100 sparrows. In return the Sultan conferred significant cash presents on the major guilds, and threw handfuls of coins at their apprentices. After that there were more military entertainments, with Albanian horsemen jousting at each other with lances; this was not mere play-acting, as several horses were killed in the process. Morale was boosted both by processions of genuine Christian captives from the Habsburg frontier, and by mass episodes of Christian Ottoman subjects, especially Greeks and Albanians, volunteering – to the dismay of Western observers – to convert to Islam. Everything went well from the Ottoman point of view, until the very last days of the festival, when serious fighting broke out between some of the Sultan’s soldiers. It started with some young spahis (cavalrymen) who were found in a brothel by a janissary patrol led by the subaşı of Istanbul. Violence began when they resisted the round-up of prostitutes, and quickly turned into public fighting between much larger numbers of spahis and janissaries. Two of the spahis were killed. Sinan Pasha blamed the ağa (commander) of the janissaries, Ferhad Pasha, and dismissed him; Ferhad would become a redoubtable rival to Sinan thereafter.

Bartolomeo presumably enjoyed the festivities, and the experience of rubbing shoulders with West European dignitaries who would have paid scant regard to him a few years earlier. But the most important element in this visit would have been his meetings with his relative Sinan Pasha, at which the future of the Voivod of Moldavia must have been discussed. Seven years later the papal nuncio in Poland would write, on the basis of what Bartolomeo had told him, that ‘because Iancu did not observe the conditions he had promised, and did not pay the tribute he had promised to Sinan Pasha, by whose means he had been appointed voivod, Bruti in Istanbul arranged for Iancu to be deposed, and for this prince Petru, the current ruler, to be appointed.’ That a failure to make the special personal payments to Sinan was a factor is easily imagined, but the claim that Bartolomeo ‘arranged’ the deposition sounds like self-aggrandizement; and it is difficult to believe that Bartolomeo, of all people, would have promoted the reinstatement of Petru Şchiopul, who could reasonably have been expected to bear a deep grudge against him for his previous dismissal. The decision was surely taken by Sinan, who obliged Petru to retain Bartolomeo’s services. Petru Şchiopul’s investiture took place in Istanbul on 28 August 1582, and he travelled to Moldavia with Bartolomeo a couple of weeks later. The Venetian bailo reported that Petru made a grand exit from Istanbul with an escort of more than 1,000 cavalry. He also wrote – again, surely on the basis of what Bartolomeo had said – that Petru was reinstated thanks to Bartolomeo’s intercession; he added, significantly, that Bartolomeo went with him ‘and will have the most important and most valuable position, having been warmly recommended by the Grand Vizier, who told him that whether he stays a long time in office will depend on the good treatment he gives to Bruti’.