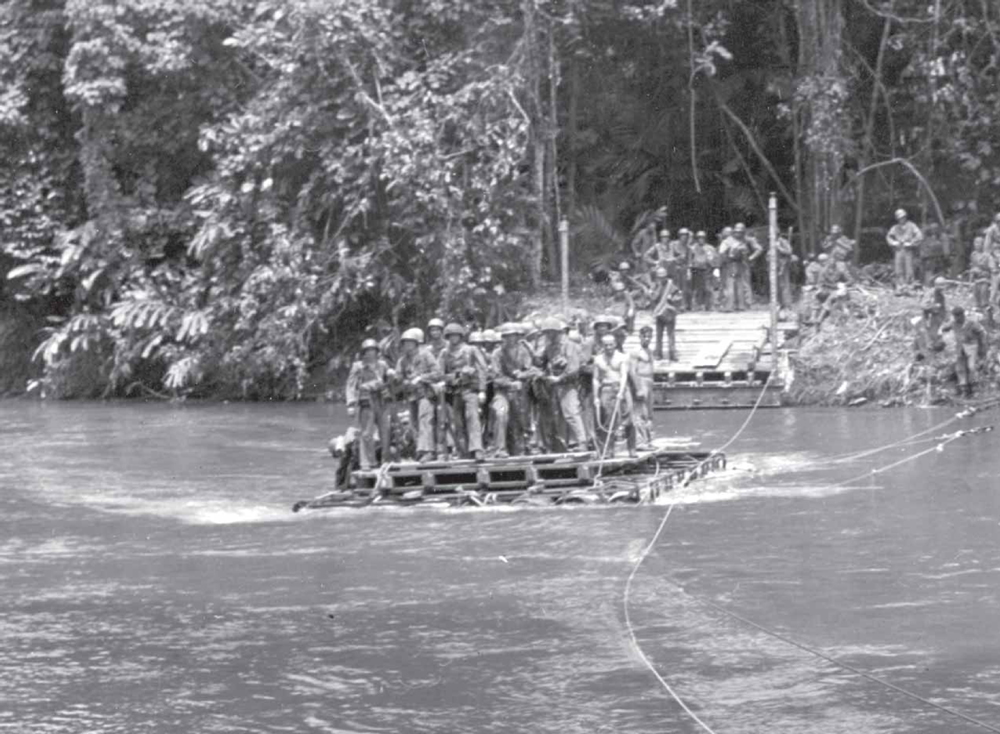

Marines cross the Matanikau River aboard a permanent ferry, complete with landing stages at both ends. The raft was fashioned by Marine engineers from 55-gallon fuel drums. (Official USMC Photo)

Map of the U.S. Marine offensive around the Matanikau, 7–9 October 1942.

November 1942 was the month in which the tide was seen to turn on Guadalcanal. It was the month in which the beleaguered Marines in the Lunga Perimeter went on the offensive.

In late October 1942, only days after the reinforced 1st Marine Division turned back the supreme Japanese ground effort to destroy the Lunga Perimeter and retake Henderson Field, General Vandegrift authorized a major offensive of his own. The Marines’ objective was to push elements of the Japanese 17th Army far enough to the west to obviate the use of Japanese 150mm long-range artillery against the American air-base complex at the center of the three-month-old land, sea, and air campaign. In what was to be the largest and strongest coordinated American ground operation to date on Guadalcanal, Vandegrift foresaw the use of six Marine infantry battalions in the attack, a U.S. Army infantry battalion in reserve, and elements of two Marine artillery regiments in support. The immediate objective was the coastal village of Kokumbona, which had once, briefly in August, been in Marine hands and which, for some weeks, had been the headquarters of Lieutenant General Harukichi Hyakutake’s corps-level 17th Army. If it was possible for the Marine battalions to drive beyond Kokumbona, they were to do so.

There were mitigating factors to be reckoned with. The main power of the new offensive was to be provided by Colonel Red Mike Edson’s 5th Marines. This renowned regiment had made the initial landings on Guadalcanal and Tulagi on August 7, and it had since been in a number of serious battles and skirmishes. The 5th Marines was a regiment in name, and its morale remained high, but it was no longer a regiment in strength. Illness, hunger, and battle casualties had withered each of the battalions, and most of the officers and men who remained were malnourished and nearing the limits of physical and emotional endurance. Two battalions of the 2d Marines, a 2d Marine Division regiment that had been on loan to the 1st Marine Division since the start of the campaign, were in slightly better shape. These somewhat larger and stronger battalions had seen far less direct action against the Japanese, but they had been subjected to as much physical and emotional abuse as the battalions of the 5th Marines. Likewise, 3/7, which had been ashore since mid-September and had seen virtually no action, had suffered losses through illness and in the course of several major bombardments leading up to the 17th Army’s October offensive. The army battalion, 1/164, ashore on Guadalcanal for a little over two weeks, was by far the strongest of the battalions assigned to the Kokumbona offensive, and it was in by far the best shape. But it had seen no combat, and that was a factor. Of the artillery battalions, all fielded short-range 75mm pack howitzers whose shells had very limited effect in the closed terrain of rain forests and coconut groves that would be encountered during the coastal sweep.

The Japanese living in the target area were known to be veteran jungle fighters, and Marine scouts reported in advance that the Japanese had dug into several formidable defensive sectors between the Matanikau River and Kokumbona. No one knew how many Japanese soldiers the assault force might encounter, nor how many other Japanese soldiers might be called in to help parry the assault.

The Marine assault battalions moved into their jump-off positions on October 31. At 0630, November 1, a platoon of Company E, 2/5, paddled across to the west bank of the Matanikau River in rubber assault boats and, without opposition, established a shallow bridgehead. Then, in the first operation of its kind undertaken in World War II, three Marine engineer companies threw three prefabricated footbridges across the Matanikau River. The rest of 2/5 quickly crossed to the west bank and attacked straight into the rain forest. At 0700, 1/5 attacked parallel to 2/5, straight up the beach and right across the sandspit at the mouth of the river. The regimental reserve, 3/5, followed 1/5. Farther inland, 1/2 and 2/2 crossed the river and hunkered down to await further orders. The last battalion to cross was 3/7, which passed through the units of the 2d Marines and advanced on 2/5’s inland flank to screen against Japanese countermoves from that direction. The supporting artillery and 1/164 remained east of the river. Working ahead of the advancing battalions were two U.S. Navy cruisers and a destroyer, which were able to deliver pinpoint, on-call fire support as well as area gunfire. And overhead, Marine SBD Dauntless dive-bombers, Army Air Forces P-39 fighter-bombers, and even Army Air Forces B-17 heavy bombers struck Japanese supply dumps, lines of communication, and the Japanese base at Kokumbona.

2/5 met very little opposition as it advanced westward along a line of inland ridges running parallel to the beach, but 1/5 bumped into powerfully manned Japanese emplacements almost as soon as it began its advance on the regimental right, along the beach. Farther south, 3/7 couldn’t find a single Japanese.

The remnants of the 2d Infantry Division’s 4th Infantry Regiment had holed up in a complex of extremely well-camouflaged mutually supporting bunkers and pillboxes around the base of Point Cruz. 1/5 had advanced directly into outposts screening the eastern side of the complex, but 2/5 had passed around the defensive position. Movement along the coast slowed to a crawl as the two leading Marine infantry companies became entangled within the Japanese defenses.

Gains by 1/5 were eventually measured in feet until, during the afternoon, the Japanese counterattacked a platoon of Company C that had extended itself too deeply. Many Marines retreated under the intense pressure, but one who did not was a determined machine gunner, Corporal Louis Casamento. Loading and firing his .30-caliber machine gun alone, Casamento stopped the Japanese in his sector and killed many of them, even though he was soon delirious with blood loss from fourteen separate gunshot wounds. As Casamento finally passed out, Company C swept forward again and retook the lost ground. Because all of the eyewitnesses to Louis Casamento’s incredible stand were wounded and scattered to the winds, it would be nearly forty years before his heroism was officially recognized in the form of a Medal of Honor.

The fight seesawed through most of the day. The 1/5 reserve company was committed without much effect, and finally two reinforced companies of 3/5 were fed in along the beach while 1/5 shifted to the left to try to find the extremity of the Japanese position. No more forward progress was made on November 1, but 1/5 and 3/5 did seal the 4th Infantry Regiment bunker complex on the eastern and southeastern flanks.

The next morning, 2/5 advanced around to the western side of the Japanese position and stretched itself to the beach. The attachment of a company from 3/5 enabled 2/5 to link up with 1/5. The 4th Infantry Regiment was sealed in at the base of Point Cruz, but it remained to be seen if the 5th Marines had the strength to root it out and destroy it.

Heavy artillery concentrations were laid on the dug-in 4th Infantry, but the shells were for the most part unable to penetrate the thick jungle growth, much less the formidable coral-and-log pillboxes that protected the Japanese. Attack after attack was beaten back by the cornered defenders, but a number of Japanese positions were inevitably reduced, so some gains were made.

On November 4, two companies each from 2/5 and 3/5 attacked toward one another along the beach. Hand-to-hand fighting on both flanks reduced several more Japanese pillboxes, and then a 37mm antitank gun was carried by hand to the 2/5 front line. Canister tore away a good deal of the dense growth in that sector and revealed a number of pillboxes, which could then be taken more easily. And so on, until the defense simply collapsed in the middle of the afternoon. A total of 239 Japanese corpses were counted, including those of the commander of the 4th Infantry Regiment and most of his staff.

After burying the Japanese dead on the spot and carrying away tons of stores and weapons, the 5th Marines prepared to continue toward Kokumbona. Before the attack could resume, the regiment was ordered to return to the defense of the Lunga Perimeter. It appeared that a Japanese attack against the perimeter’s eastern flank was imminent. The 5th Marines did withdraw, but the Point Cruz area—which had been repeatedly attacked and even occupied several times since August—was not abandoned; 1/2 and 2/2 were left on the newly conquered ground, and 1/164 was placed in a reserve position a short distance away. The Marines had fought their way across the Matanikau River for the last time.