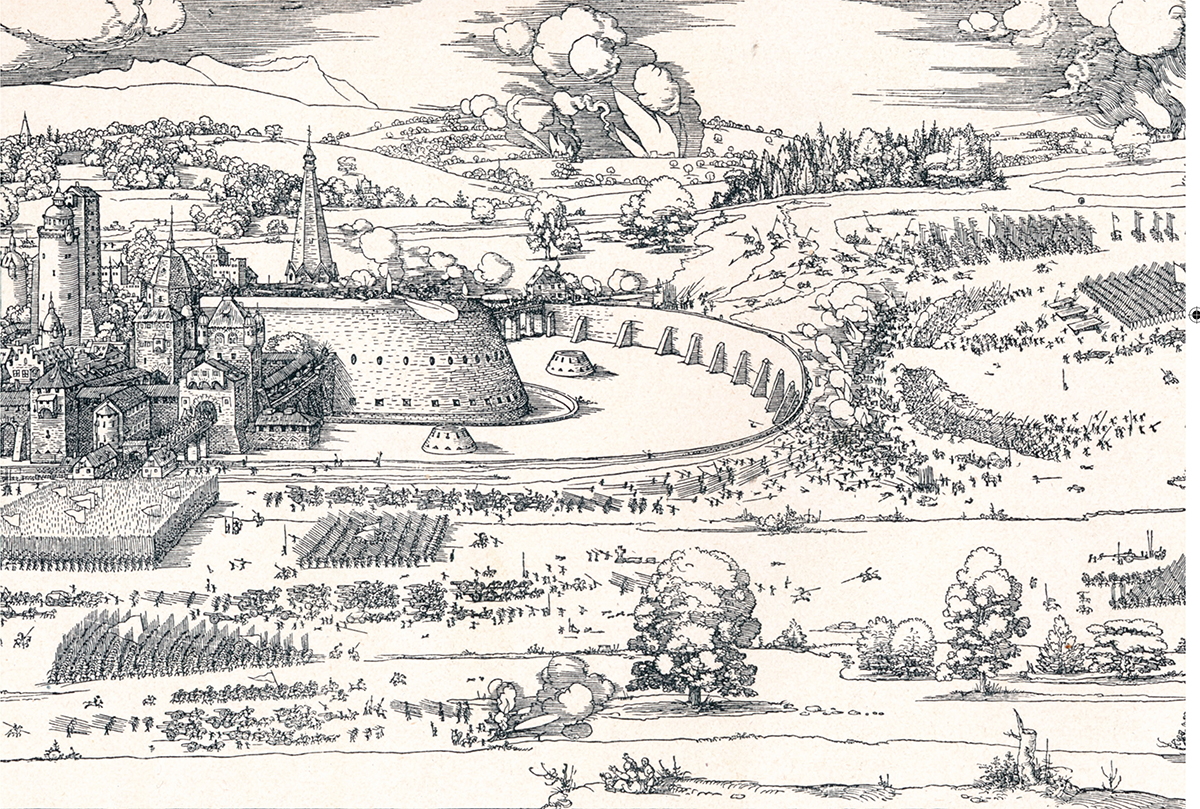

THE SIEGE OF A FORTRESS, BY ALBRECHT DÜRER, 1527 In 1527, Dürer published a treatise on fortification that proposed walls dominated by massive squat roundrels, towers that would also provide gun platforms. Strengthened by earth and timber, such squat towers were better able to take bombardment than high walls. This indicated that not everyone adopted the Italian alla moderna system of low, bastioned defences.

SIEGE OF BOULOGNE, FRANCE, 1544 Henry VIII’s attempt to expand the English position in the Pas de Calais led to the siege of Boulogne from 19 July. The lower section of the town fell rapidly, but the upper town proved more difficult and was put under bombardment, as shown here. Its walls were eventually breached and when the English dug tunnels under the castle, the French surrendered on 13 September. The English had deployed more than 250 pieces of heavy ordnance, including mortars firing exploding cast-iron balls. The following month, a French assault on Boulogne was beaten back. The English then heavily fortified Boulogne, beating off a French attack in 1549, but in 1550 it was returned to France as a result of negotiations.

MUSCAT, OMAN Al Jalali Fort in Muscat was built in 1586–88 to protect the harbour of Portuguese-ruled Muscat from Ottoman (Turkish) attack; the Ottomans had captured Muscat in 1552 and 1582. Named Forte de São João, the fort was built on top of a rocky prominence and included a gun deck designed to dominate the harbour. In 1650, Sultan bin Saif of Oman captured Muscat. The fort, now named al-Jalali, played a role in the civil war and Persian intervention of the early eighteenth century. After Ahmad bin Said al-Busaidi, the first ruler of the Al Said dynasty, captured the fort in 1749, he renovated it, adding the large central buildings and the round towers. Disputes among the ruling family ensured that the fort played a significant role in 1781–82. It subsequently became Oman’s major prison.

The spread and increasing sophistication of cannon became much more of a factor in the attack on fortifications, and their defence in the sixteenth century, although the situation varied greatly across the world. When the Spaniards arrived in Manila Bay in the Philippines in 1572, the local communities were defended only by a bamboo stockade at the entrance to the Pasig River, and only one stone fort is known to have existed in the Philippines before the Spaniards arrived.

In Christian Europe, in a very different context, cannon were most effective from the fifteenth century and, even more, the sixteenth, against the stationary target of high stone walls. As a result, fortifications were redesigned to provide lower, denser and more complex targets. There were developments and adaptations to resist cannon prior to the better-known system alla moderna (more recently called the trace italienne), including adding masonry reinforcements to existing towers and sloping skirts at the base of walls. The boulevards used, as at the siege of Orléans in 1429, were earth and timber outworks constructed to keep the besiegers from running their cannon close to the walls.

Nevertheless, fortifications designed to cope with artillery were first constructed in large numbers in Italy and were then spread across Europe by Italian architects. In this new system, bastions, generally quadrilateral or pentagonal, angled, and at regular intervals along all walls, were introduced to keep the besieger from the inner walls and to provide gun platforms able to launch effective flanking fire against attackers. Cannon were placed on the ramparts, which helped ensure that the defence could be active. The use of planned fire zones by the defence was more important than the strength brought by height, whether of position or of walls. Defences were lowered and sunk in ditches, obliging the attacker to expose their batteries, and the defences, strengthened with earth to minimise the impact of cannon fire, were slanted to help defeat cannonballs. There were similar designs in Japanese castles. These improvements in fortifications lessened the impact and decisiveness of artillery in siegecraft.

The often-cited idea that cannon brought the value of medieval fortifications to an end, and thus brought the medieval military system to a close, requires qualification. Even when cannon were moved up to take part in sieges, itself a difficult process in the transport system of the age, they were frequently only marginally more effective than previous means of siegecraft. Indeed, cannon initially failed more often than they succeeded, and many times a castle fell to treachery or negotiation, rather than bombardment. In addition, stormings, rather than sieges, were also important, as during the Italian Wars, when the French stormed Venetian-held Brescia in 1512.

Nevertheless, with the demise of the siege tower and the battering ram, siege operations in 1550 were different to those of two centuries earlier and were far more focused on cannon. At the successful English siege of Boulogne in 1544, more than 250 pieces of heavy ordnance were deployed, including mortars firing exploding cast iron balls. The introduction and effects of gunpowder weapons were gradual processes, more akin to evolution than the overused term revolution. Similarly, in response to gunpowder, there were a number of much cheaper ways to enhance existing fortifications than the system alla moderna, and these other methods were used much more extensively. As is always the case, most positions were not fortified at the scale and expense of the best-fortified locations. As a result, most sieges did not match the major and lengthy efforts mounted against the latter. Examples of such efforts included the eventually successful efforts mounted by Spain, in opposing the Dutch Revolt, against Antwerp in 1585 and Ostend in 1601–04, both well-defended as well as strongly fortified.

The largest new fortifications in Europe, those at Smolensk in Russia built between 1597 and 1602, were built in the traditional fashion with a high stone wall 6.5 kilometres long and 13–19 metres high, strengthened by towers. The vulnerability of high stone walls, however, meant that such fortifications were increasingly regarded as anachronistic. Indeed, Smolensk’s walls were breached by the besieging Poles in 1611 and by the Russians, when they recaptured it in 1654.

In general, fortifications were of most value when combined with field forces able to relieve them from siege. Indeed, many campaigns revolved around attempts to mount sieges and, in response, to relieve besieged positions. As a result of the latter, sieges led to major battles such as Pavia (1525), Nördlingen (1634) and Rocroi (1643). Sieges, moreover, were frequently determined not by the presence of wall-breaching artillery, but by the availability of sufficient light cavalry to blockade a fortress and dominate the surrounding country. Sieges accentuated the logistical problems that were so difficult for contemporary armies, as besieging forces had to be maintained in the same area for a considerable period, thereby exhausting local supplies.

Other factors were also involved in fortification, and in the campaigning linked to it. In terms of significance of power, the demonstration of force by means of fortifications could be more important than their specific usefulness in action. So also in attacks on fortresses. Thus, many sieges ended not with particular operations, but with a surrender in the face of a larger besieging army. This was a relationship that could be almost ritualistic in its conventions, and not only in Europe.

EXPANSION WITH THE AID OF FORTS

Outside Europe, Western expansion was anchored by fortresses. This was seen across the oceans and with the eastward expansion of Russia. In the latter case, forts were established at Samara and Ufa in 1586, and then, across the Urals, at Tyumen in 1586 and at Tobolsk, on the River Ob, in 1587. In their expansion, the Russians did not face fortresses in Siberia, but they did when they attacked Islamic opponents, notably the khanate of Kazan. This was a key target for Ivan IV, ‘the Terrible’ (r. 1533–84). Kazan, long an opponent of Russia, not least as a source of slave-raiding by light cavalry, stood on a high bluff overlooking the Volga River. It had double walls of oak logs covered over with clay and partially plated with stones. These were formidable defences, even if they did not match the defences of the alla moderna. There were 14 stone towers with cannon and a deep surrounding ditch. Such ditches posed an obstacle to attackers, accentuated the height of the defensive walls, and made it much harder to undermine them. This factor remained a constant with fortifications.

The garrison of Kazan consisted of 30,000 men with 70 cannon, which was both a formidable force and the main army of Kazan, although there was also a light cavalry army, about 20,000 strong, that sought to harass the besiegers. Ivan attempted two winter campaigns against Kazan in 1547–48 and 1549–50, but these failed because the Russian army had no fortified base in the region, had to leave its artillery behind because of heavy rains, and ended up campaigning with an exclusively cavalry army that was of no use in investing the fortress of Kazan.

But for the third campaign, a base was secured. In the winter and spring of 1551–52, the Russians prefabricated fortress towers and wall sections near Uglich and then floated them down the Volga on barges with artillery and troops to its confluence with the Sviiaga, 25 kilometres from Kazan. Here, the fortress of Sviiazhsk was erected in just 28 days, providing a base. That summer, siege guns and stores were shipped to Sviiazhsk and a Russian army, allegedly 150,000 strong, with 150 siege guns, advanced, reaching Kazan on 20 August. The Russians constructed siege lines from which cannon opened fire and used a wooden siege tower carrying cannon, which moved on rollers. The ditch surrounding the city was filled with fascines and sappers tunnelled beneath the walls. The mines were blown up on 2 October, destroying the walls at two of the gates, upon which the Russian army, drawn up into seven columns, attacked all seven of the gates simultaneously. They soon broke through, and Kazan fell with a massive slaughter of the defenders. The furthest north of the Islamic khanates had fallen. Ivan exploited his success by moving down the Volga valley to capture Astrakhan in 1556 and to establish Russian power on the Caspian Sea. Thus, the capture of a major fortress had major and lasting strategic consequences for Russia and its neighbours.Overseas, the European powers were similarly dependent on fortifications. This was the case with both Portuguese and Spanish expansion, and subsequently with that of England, France and the Dutch. With limited manpower, the Portuguese Empire depended on the combination of fortified positions, notably citadels at ports such as Goa, Malacca, Mombasa, Mozambique and Muscat, with warships that used these ports. Spain was in a similar situation, although, alongside fortifications at ports such as Veracruz, Havana, St Augustine and Cartagena, more of its fortifications protected inland centres of government, such as Mexico City.

OTTOMAN FOCUS ON MOBILITY

That the Ottomans (Turks) did not have a fortification re-evaluation equivalent to that of the Western Europeans, in expenditure or style, was not so much due to a failure to match Western advances, as because the Ottomans scarcely required such a development as they were not under attack. Moreover, the Ottoman emphasis on field forces and mobility, as well as their interest in territorial expansion, ensured that they were less concerned with protecting fixed positions. In contrast, Western losses of fortresses to the Ottomans early in the sixteenth century, such as Modon (1500), Belgrade (1521), and Rhodes (1522), as well as a lack of confidence in mobile defence, encouraged the introduction of the new angle-bastioned military architecture, which the Venetians were very quick to use in their empire. The Ottomans deployed 22 cannon and two mortars against Modon, firing 155–180 shot daily.

In 1529, the Ottomans were less successful when they attacked Vienna, the walls of which were 300 years old. Niklas von Salm conducted a vigorous defence, showing how fortifications could be rapidly enhanced and expanded at times of need. The energy and skill with which this was done was a key element in any successful defence and should not be detached from discussions of fortifications or treated as inherently secondary. Salm blocked Vienna’s gates, reinforced the walls with earthen bastions and an inner rampart, and levelled any buildings where it was felt to be necessary. This defence exacerbated the problems posed for the Ottomans by beginning the siege relatively late in the year. Having withstood the assault, Vienna afterwards constructed massive, purpose-built, encircling fortifications.

When the Ottomans needed fortresses they built them, for example along the Damascus to Cairo and to Mecca roads in order to protect travellers on these important routes from attacks by Bedouin Arabs, and at the southern end of the Red Sea. In the Van region of eastern Anatolia, an area threatened by the Safavids of Persia, the Ottomans heavily fortified a line of towns around the lake. Fortifications both held off the Safavids and also served to overawe the Kurds. In 1582, a chain of seven fortresses was built on the Red Sea coast from Suakin to Massawa in order to consolidate its capture from Ethiopia. In the seventeenth century, there were also to be important Ottoman fortifications in Yemen.

ASIAN FORTIFICATIONS

Fortresses, moreover, played a role in Japan. The extent of instability and civil warfare in the sixteenth century encouraged fortifications. However, the need for them in turn fell as cohesion and unity were imposed. Japanese castle building responded to gunpowder by combining thick stone walls with hilltops of solid stone. Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the unifier of Japan in the 1580s and 1590s, proved successful in siegecraft, as with the fall of Odawara and other Hojo fortresses in eastern Honshu in 1590. Cannon became more important from the 1580s, but Hideyoshi’s success in sieges also owed much to other factors, notably the use of entrenchments to divert the water defences offered by lakes and rivers. These entrenchments threatened fortresses with flooding by rising waters, or with the loss of the protection by water features on which many in part relied. This was more generally true of many fortresses, not least because of their role in protecting crossing places against rivers, a function that remains significant to the present day.

In India, Akbar, the expansionist and successful Mughal Emperor (r. 1556–1605), anchored his position in northern India with a number of fortresses, especially Agra, Allahabad, Lahore, Ajmer, Rohtas and Attock. Sieges were also significant. Logistics played a major role in them, while negotiations frequently accompanied sieges as part of the process by which the display of power was intended to produce a solution. Not always, however. In 1567, Akbar declared a jihad against Udai Singh, rana of the Rajput principality of Mewar. Initial attacks on the Mewar fortified capital of Chittaurgarh (Chittor), which stood high on a rock outcrop above the Rajasthan plain, were repulsed, and Akbar resorted to bombardment and the digging of mines: tunnels under the walls filled with explosives. The latter were especially helpful in producing breaches in the walls, although the construction of a sasbat (or covered way) to the walls to cover an attack was also very significant. After a night-time general attack, the city fell in 1568, with all the defenders and 20,000–25,000 civilians killed in hand-to-hand fighting. The fortress was then destroyed. Hilltop locations reflected the major value of topography to the defence and the political message of overawing offered by fortresses. Fortification alla moderna was introduced to India by the Portuguese, who were also probably responsible for circular bastions there, but the diffusion of these techniques was limited.

In China, the military strength of the Ming empire (1368–1644) lay more in fortifications than in firearms. The majority of the army served against the Mongols along the vulnerable northern frontier where there was a series of major garrisons in the complex known as the Great Wall. This provision became increasingly important as Mongol attacks became much more serious in the mid-fifteenth century, and then again in response to ultimately successful Manchu attacks in the early seventeenth. The Chinese sought to cope by relying on walls and on garrisons at strategic passes. As a result, terrain and topography were to be aided by fortifications.

Numbers were crucial in Chinese siege techniques. The earlier use of gunpowder in China ensured that their fortified cities had very thick walls, which were capable of withstanding the artillery of the sixteenth century and earlier. As a consequence, assault, rather than bombardment, was the tactic used against fortifications. This was also appropriate to the large forces available. The risk of heavy casualties could be accepted, a matter both of pragmatic military considerations and of cultural attitudes towards loss, suffering and discipline. Sieges had to be brought to a speedy end because of the serious logistical problems of supporting large armies, which encouraged storming attempts.

DISREPAIR AND ABANDONMENT

Alongside improvements in fortification techniques in particular areas, there was also a destruction of fortifications, deliberate or by neglect, with the latter proving especially important in the rotting of wood and the filling in of ditches and moats by debris. There was also the neglect seen in deciding not to enhance fortifications, notably to counter new developments in artillery. Moreover, governments actively sought to weaken the military resources of real and potential domestic adversaries. As a result, building fortifications could become a questionable step. Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham, began the construction of Thornbury Castle in 1511 when he was high in the favour of Henry VIII, but they fell out in 1521; Buckingham’s construction of the castle was one of the charges in the indictment that led to his execution for treason. The castle had six towers with machicolations and a gatehouse on the late-medieval pattern. The castle was confiscated by Henry.

Social élites, notably across much of Western Europe, tended to look to the Crown and, in doing so, to abandon earlier tendencies to resist unwelcome policies by violence. For example, in England the shift from castle keep to architecturally self-conscious stately home was symptomatic of an apparently more peaceful society and a product of the heavy costs of castle building. Castles appeared to be redundant in the face of royal armies, as with the suppression of the Northern Revolt against Elizabeth I in 1569. In 1588, in response to the threat from the Spanish Armada, there were hasty preparations – cannon were mounted on castle walls; but the defences of England primarily rested on the fleet and the army.

Most fortifications in England were in a poor state. There had been an extensive abandonment of castles, in some cases from the 1470s, and far more actively under the Tudors who came to power in 1485. Dunstanburgh Castle was already much ruined in 1538 and Dunster Castle in 1542, as a consequence of a lack of maintenance for decades. In 1597, a survey found that Melbourne Castle was being used as a pound for trespassing cattle, and it was demolished for stone in the 1610s. John Speed described Northampton Castle in 1610: ‘gaping chinks do daily threaten the downfall of her walls.’ When, in 1617, James I visited Warkworth Castle, earlier a mighty fortress, he found sheep and goats in most of the rooms. Bramber Castle, formerly a Sussex stronghold of the Howards, was in ruins.

The major fortresses built in England during the sixteenth century were for frontier defence, and not for mounting or resisting rebellion. In particular, on the pattern of the Roman forts of the Saxon Shore, Henry VIII responded to the alliance in 1538 between the Emperor Charles V and Francis I of France, and the consequent fears of invasion by building, in the 1540s, a series of coastal fortifications on the south coast of England, including Camber, Deal and Walmer. These mounted cannon in order to resist both bombardment by warships and attack by invading forces. More generally, the anchorages on the south coast were to be protected by fortifications, for example Dartmouth Castle. The biggest single new fortified position was Berwick-on-Tweed, the principal fortress intended both to protect northern England from invasion and, more particularly, to provide a base from which attacks could be mounted on Scotland and notably on its capital, Edinburgh. The fortress also protected the anchorage in the estuary of the River Tweed. The modern new defences were very different to the castellated medieval ones there.

In Wales in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, many castles were abandoned or, as with Beaumaris and Conwy, fell into disrepair, while others were enhanced not with fortifications but with comfortable and splendid internal ‘spaces’, especially long galleries, as at Raglan, Powis and Carew. It was not only in Britain that castles fell into ruin. The same was true elsewhere. Thus, in the United Provinces (Dutch Republic), new fortified positions were concentrated in frontier regions, as, in particular, at Breda, but ruined castles were recorded by painters, for example Jacob van der Croos’ Landscape with Ruined Castle of Brederode and Distant View of Haarlem. Built in the third quarter of the thirteenth century and rebuilt a century later, the castle was set on fire by Spanish forces in 1573.

Increasingly, the new fortifications of the sixteenth century and later might provide lodgings for their garrisons, but generally were not private and domestic in the medieval tradition. Instead they were instruments of the state, as in the Roman period.

At the same time, civil wars, such as the German Peasants’ Revolt, the Dutch Revolt and the French Wars of Religion, put a continuing premium on older fortifications, both castles and city walls. They could thwart or delay attacking forces, and thus have a major operational, even strategic, impact, which was the case in all three of these conflicts. For example in France, the fortifications of the Protestant-held town of La Rochelle successfully resisted a Royalist siege in 1572–73, although it fell in 1628 after a 14-month siege.

CULTURAL FACTORS

Cultural factors were important to fortification. This was clearly seen in South-East Asia where most cities, for example Aceh, Brunei, Johore and Malacca, were not walled in the medieval period. However, in response to European pressure, construction of city walls spread in the sixteenth century, for example in Java. Nevertheless, the notion of fighting for a city was not well-established culturally. Instead, the local culture of war was generally that of the abandonment of cities in the face of stronger attackers who then pillaged them before leaving. As in parts of Africa, captives, not territory, were the usual objective of operations. European interest in annexation and the consolidation of position by fortification reflected a different culture. Thus, the role of fortifications in part depended on cultural factors, a point that is more generally true of conflict. This was the case not only with the prudential value of these fortifications, but also with their symbolic significance.