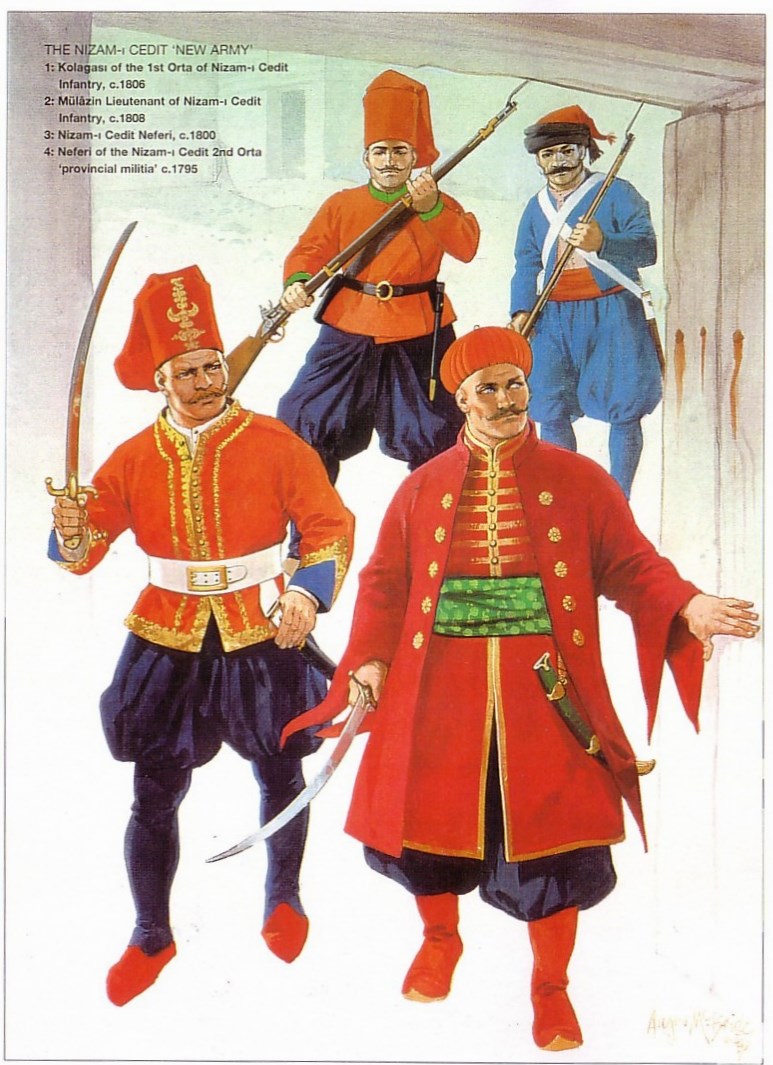

Ottoman Army Early 19th Century.

Portrait of Mikhail I. Kutuzov. G. Dawe, 1829. After Count Kamensky died in April 1811, Kutuzov was appointed commander-in-chief of the Danube army. Several months were dedicated to preparation, and on June 22 (July 4), 1811, the Russian army thoroughly defeated the outnumbered Turkish army (15 to 20,000 against 60,000) near Ruse (Turkish: Rusçuk). Soon, another part of the Turkish army was blocked and then captured near Slobozia.

Hostilities had opened between Russia and Turkey soon after Russia and Austria had been humiliated at Austerlitz in 1805. The following year Sultan Selim III had deposed the pro-Russian Hospodars of Wallachia and Moldavia (parts of modern-day Romania), whilst France occupied Austrian Dalmatia. This seriously threatened what was known as the ‘Danubian Principalities’, consisting of modern-day Romania and Serbia. Russia looked upon these areas as a safeguard against any possible attack on Russian territory from the Balkans. Fearing such an attack, Russia promptly advanced a force of some 40,000 men into the principalities to deny them to any others, particularly France. The sultan’s reaction was decisive, declaring war and blocking off the use of the Dardanelles to Russian ships. The subsequent actions of Admiral Seniavin and his victory over the Turkish fleet at Athos, and the deposing of Selim III have already been covered.

The Turkish armies had not performed any better than their fleet. Count Gudovich with 7,000 men had destroyed a Turkish force numbering no fewer than 20,000 men at Arpachai on 18 June. A vast Turkish army advancing into Wallachia was also defeated at Obilesti three days later, on 21 June 1807, by General Mikhail Miloradovich, with just over 4,000 troops.

The war might well have petered out at this point had not the Treaty of Tilsit enabled the Russians to transfer large numbers of their troops from central Europe to Bessarabia, bringing the size of their army up to 80,000 men. However, this sizeable force, under the ageing Field Marshal Prozorovsky, achieved virtually nothing, losing great numbers of troops in a vain attempt to storm the fortress of Brailov. Eventually, in August 1809, Prozorovsky was superseded by Prince Bagration, who immediately crossed the Danube with the army and laid siege to Silistra, but abandoned the attempt on the advance of a Turkish relieving army.

Hostilities were renewed in 1810 with Count Nikolay Kamensky (who had superseded Bagration) defeating these Turkish reinforcements and again attacking Silistra, which finally surrendered on 30 May. Kamensky tried to take a number of other fortresses without success, which cost him a great deal of time and huge numbers of casualties, but he did succeed in defeating a 40,000-strong Turkish army at Vidin on 26 October. In February 1811 Kamensky fell ill and died, leaving his forces under the command of General Louis Andraut de Langeron. But for all of this fighting, and despite numerous successes, Russia was no closer to a final victory.

Relations were also beginning to sour between Napoleon and Alexander over Russia’s clear disregard for the Continental System,1 and therefore Alexander appointed his favourite, General Mikhail Kutuzov, to command his forces in the south with clear orders to force Turkey to the peace table as quickly as possible. Kutuzov astounded everyone, promptly evacuating Silistra and beginning a retreat northward. The Turks took confidence from this manoeuvre and an army of 60,000 men was amassed at the fortress of Shumla. Kutuzov’s army, numbering some 46,000, finally stood against the Turks at Rousse on 22 June 1811 and defeated the Turkish hordes. Kutuzov, however, did not take advantage of his victory, but rather ordered his army to retire once again into Bessarabia. Alexander was livid at this retreat and demanded an explanation, but Kutuzov simply said nothing.

In late October 1811 the Turkish army under Lal Aziz Ahmet Pasha, of around 70,000 men, began to cross the Danube. Some 50,000 men crossed the river, whilst the remaining reserve of 20,000 remained on the eastern bank guarding the stores and food supplies. On the night of 2 November 1811 a large Russian cavalry force crossed the Danube and launched a terrible attack on the Turkish reserve, destroying it completely and slaying around 9,000 men. The main Turkish army was now stranded on the western bank and virtually surrounded; even more seriously, all their supplies had also been captured. At this point Kutuzov launched an all-out attack. He surreptitiously allowed the Pasha to escape, knowing that the Grand Vizier was forbidden from ever taking part in any peace negotiations. With him gone, Kutuzov sought negotiations and after some procrastination peace was signed with Turkey on 28 May 1812, Russia gaining Bessarabia by the treaty.

Peace with Turkey was urgently needed as Napoleon had spent the spring of 1812 in drawing troops from every corner of Europe to congregate in Poland, to form the largest army the world had ever seen. Napoleon was about to invade Russia; nobody knew how it would end at that moment, but that decision was going to change everything. As the campaign season arrived in 1812, few realised how momentous the following six months would be in world history and how rapidly the balance of power in Europe would change. This was as true in the Mediterranean as anywhere else.

But we cannot ignore another war that broke out that summer; it had been brewing for some time and had the potential to seriously hamper British efforts against Napoleon. For years the rapidly expanding American merchant fleet had been complaining loudly against the British insistence on their right to board American ships and to remove any British men found on board. This high-handed approach had caused serious resentment, particularly when American sailors were wrongly accused of being British and were taken off to serve in the Royal Navy. In reality, there was wrong on both sides. Whilst the Americans claimed that some 5,000 American sailors were taken into the British navy, it also has to be admitted that America’s merchant fleet had grown so rapidly, acting as a neutral carrier, that they had enticed some 10,000 British merchant seamen to join their ships for higher wages. It is also true that numerous American ships had been detained by the British for breaking the rules on supplying materials to Napoleon’s Europe, but again it was true that French frigates and privateers had been equally guilty of capturing hundreds of American merchant ships. Indeed, the American government became so upset with Britain and France over these issues that it contemplated going to war with both at the same time! However, sanity prevailed and on 12 June 1812 President Maddison declared war on Britain.

This involved a number of embarrassing single-ship defeats for the British navy and an unsuccessful American invasion of Canada. But even during the height of this war, American merchant ships continued to be granted licences to ship badly needed grain to Spain to feed Wellington’s army. However, this war had virtually no effect on the war in the Mediterranean, except for the capture of an odd American merchant vessel to boost prize money.

The Russian-Turkish and Russian-Persian Front Line on the Eve of

and During the Patriotic War of 1812

Download

The research paper examines the attempts by the Ottoman and Persian Empires to destabilize the situation in the North-Western Caucasus and Transcaucasia on the eve and during the Patriotic War of 1812. It focuses on countermeasures against the Turkish plans, taken by peaceful Circassian princes and Russian regional administration. With the use of new archival documents, we were able to reconstruct the picture of Circassian raids on the Russian territory in 1812—1814. The paper also retrace the picture of the Kakheti uprising and its orchestrating process considering Napoleon’s invasion of the Russian Empire. The sources used to prepare the work include archival documents stored at the State Archives of the Krasnodar Krai, Krasnodar, Russia, and the Central State Historical Archives of Georgia, Tbilisi, Georgia. A considerable part of the archival material has never been published before. In conclusion, the authors note that both Persia and Turkey strove to widely leverage the war between Russia and France to their own advantage. The consolidated efforts of the Russian administration thwarted the attempt by Turkish intelligence agents in Circassia to use the anti-Russian Circassian militia in combat operations against Russia. At the same time, Persia achieved impressive progress in destabilizing the situation in Transcaucasia. The uprising was led by Georgian Tsarevich (An heir apparent of a tsar) Alexander, and the region of the uprising comprised Kakheti. In the area, Russian troops had small garrisons that were to protect Kakheti and central Georgia from Lezgin attacks. It was them who fell victim to insurgents. In terms of the number of casualties among the Russian army soldiers, the uprising in Kakheti in 1812 can be described as the deadliest incident in Transcaucasia in the 19th century. At the same time, the Treaty of Bucharest and Treaty of Gulistan, which ended the Russo-Turkish (1806—1812) and Russo-Persian (1804—1813) wars, were the first diplomatic acts that legally formalized a fait accompli — the annexation of a large part of Transcaucasia to Russia.

Source: Aleksandr A. Cherkasov, Larisa A. Koroleva, Sergei Bratanovskii, Nugzar Ter-Oganov (2019). The Russian-Turkish and Russian-Persian Front Line on the Eve of and During the Patriotic War of 1812. Bylye Gody. Vol. 52. Is. 2: 585-595