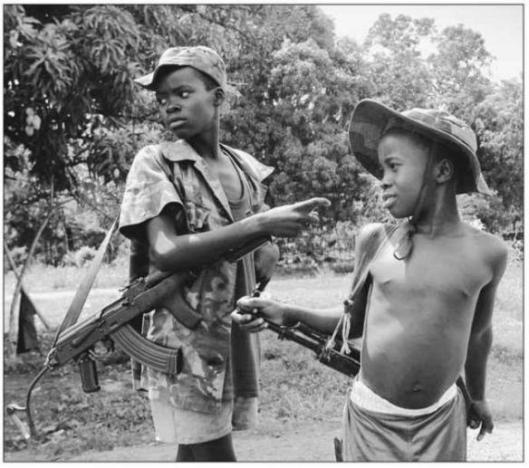

Because AKs are inexpensive, easy to fire, require almost no training, need few repairs or maintenance, they are ideally suited for child soldiers. As many as 80 percent of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) rebels in Sierra Leone, shown here, were boys and girls between seven and fourteen.

Within seven months of his invasion, barely noticed by the outside world, Taylor and an estimated five thousand guerillas reached the outskirts of Monrovia with their sights set on the presidential mansion where Doe had hunkered down. Despite his oppressive regime, Doe’s government had received more than half a billion dollars from the United States since the 1980s. In exchange, Doe pushed out the Soviets and permitted U.S. access to ports and land.

During the capital’s siege, U.S. Marines offered Doe safe passage out of Liberia in August along with U.S. citizens and other foreign nationals, but he refused. Doe’s rule ended during a shootout with a breakaway faction of Taylor’s NPFL group led by Prince Yormie Johnson even though the president was under the protection of a four-thousand-man peacekeeping force sent by the six-nation Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Johnson seized the opportunity to capture Doe when Taylor’s soldiers temporarily faltered in their forward progress just outside the city. A wounded Doe was carried away to Johnson’s camp, where he later died either from his gunshot wounds or from torture and execution, depending upon who told the story. His mutilated body was put on public display.

The rift between Taylor and Johnson led to six more years of bloodshed as seven rival factions, separated mainly along tribal lines, joined the conflict and fought for control of the country’s natural resources, including iron, timber, and rubber. The brutal warfare continued as more light weapons reached the combatants. One of the last and darkest moments was the April 6, 1996, siege of Monrovia, during which an estimated three thousand people were killed as five factions converged on the capital. After several unsuccessful cease-fires brokered by ECOWAS and others, major hostilities finally ended. In 1997, elections were held.

Some international observers, including former U.S. president Jimmy Carter, deemed the elections fair, and Taylor received 75 percent of the votes. Others believed that citizens were afraid to vote for anyone else. Moreover, many Liberians feared that Taylor would resume the war if he was not elected.

With the elections drawing world attention, those outside Liberia began to understand the staggering effects of the war. More than 200,000 people were killed, most of them civilians, and another 1.25 million became refugees. Through the use of his AK-BASED system of warfare and intimidation, Taylor became one of the richest warlords in Africa, pulling in $300 to $400 million in personal income through looting and illegal trading of commodities and arms.

The impact on a generation of children was devastating. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), fifteen thousand to twenty thousand children participated in the Liberian civil war between 1989 and 1997; perhaps as many as 60 percent of the combatants in some factions were under eighteen, with some as young as nine years old.

Unfortunately, Liberia’s violence did not end with Taylor’s election. With the country’s infrastructure in shambles, heavily armed gangs continued to roam the countryside, stealing food and other necessities. People were afraid to give up their AKs, which now represented a way to make a living, albeit a ruthless one, in a country with little opportunity for legitimate work.

Despite a UN embargo imposed on Liberia in 1992, small arms continued to enter the country. Indeed, the United Nations charged that Taylor was a major arms conduit in Africa, operating with impunity and giving shelter to well-known arms dealers such as Gus Kouen-Hoven, a Dutch national who ran the Hotel Africa outside Monrovia. Also prospering under Taylor’s largesse was the notorious Russian trafficker Victor Bout, one of the world’s most active and notorious arms dealers. Bout’s specialty was handling small arms from the Soviet Union and former Soviet states. Another Taylor-connected trafficker was the Ukrainian Leonid Minin, who, UN officials said, supplied arms to Taylor for money but also to win timber export contracts for his company, Exotic Tropical Timber Enterprise. These men made repeated appearances throughout Africa, selling small arms, mainly AKs and RPGs, to insurgents, rebels, and even legitimate armies.

In 1999, Taylor’s regime faced opposition from a group better organized and more effective than the others he had encountered. Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy, commonly known as LURD, reportedly backed by U.S. ally Guinea, was consolidating control in the northern part of Liberia using many of the same tactics and engaging in similar atrocities as Taylor. Several other anti-Taylor groups emerged, including the Movement for Democracy in Liberia (MODEL), allegedly backed by neighboring Ivory Coast, which maintained a stronghold in the southern part of the country. Slowly and amid continued bloodshed, Taylor’s grip on the nation was slipping away. In desperation, Taylor launched Operation No Living Thing, a campaign of atrocities designed to deter civilians from supporting and aiding LURD, whose ranks had swelled with Sierra Leonean militia wanting to destroy Taylor’s regime. Taylor’s terror program failed, and by the end of 2003 he controlled less than a third of Liberia.

A UN tribunal issued a warrant in June 2003 for Taylor, charging that he had exported his brand of AK-based carnage to neighboring Sierra Leone. His instrument there was the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), a group that he surreptitiously funded through the sale of weapons and timber. Again, unlike traditional conflicts, neither territory nor ideology were goals. Taylor’s interest in Sierra Leone was its diamond mines, one of the largest deposits in the world. In March 1991, the RUF, under the command of former army corporal Foday Sankoh, gained control of mines in the Kone district. A small band of men, mainly armed with AKs, pushed the government army back toward the capital city of Freetown. Widespread civil war ensued, but this time it was more brutal than anyone had envisioned, even eclipsing Liberia in its depravity.

To maintain control of these diamond mines, the Taylor-backed RUF fighters engaged in atrocities against workers and others never before witnessed in Africa. Using AKs and wholesale rape, torture, mutilations, and amputations of arms and legs of those who opposed them, the RUF terrorized Sierra Leone. Within several years, the group controlled 90 percent of the country’s diamond-producing areas.

Taylor repeatedly denied any involvement, but the statistics on diamond exports belied his claims. Liberia’s annual mining capacity had been 100,000 to 150,000 carats annually from 1995 through 2000, but the Diamond High Council in Antwerp, Belgium, recorded imports into that country from Liberia of more than 31 million carats. According to U.S. ambassador Richard Holbrooke’s testimony before the UN Security Council on July 31, 2000, the RUF gained $30 to $50 million annually, maybe as much as $125 million, from the illicit sale of diamonds. At the same time, exports from Sierra Leone slowed to a trickle, from $30.2 million in 1994 to $1.2 million in 1999.

The originating point of diamonds is pegged to their country of export, not the country of origin, so tracing is virtually impossible; however, Liberia’s diamonds could only have come from Sierra Leone. Taylor sold these “blood diamonds,” or “conflict diamonds,” as they became known, or traded them for small arms directly or through countries like Burkina Faso, Guinea, Ivory Coast, and Togo, whose exports of diamonds on the world scene also showed unexplainable increases. Arms dealer Leonid Minin also involved himself in the illegal diamond trade as a way to finance arms purchases for Taylor and others in West Africa.

As the years progressed, Taylor found many ways to escape detection for his arms transfers. In 2002, however, the United Nations officially documented a shipment of five thousand AKs from Serbia to Liberia in violation of an arms embargo. Although UN officials had been trying to obtain documented proof of illegal arms shipments to Taylor, hard evidence had always been difficult. In this one case, however, UN weapons inspector Alex Vines painstakingly traced the small arms, starting on the battlefield. He began his investigation in a no-man’s-land in the middle of the Mano River Union bridge between Sierra Leone and Liberia. “A rebel child soldier showed me his AK-47 assault rifle which was stamped with M-70 2002 and a serial number. I knew immediately that this weapon had been made in Serbia,” Vines said. The M-70 is the Yugoslav version of the AK. The child relayed that the weapon had recently been captured from a Liberian government soldier he killed. Discussions with officials in Belgrade showed a certificate on file for a sale to Nigeria, but close inspection revealed the document as a forgery. Further investigation showed that about five thousand AKs had traveled by plane to Libya where the plane was supposed to refuel en route to Nigeria. But instead of terminating in Nigeria as intended, the plane had continued on to Liberia.