Jaime I

While the other Christian rulers were crusading against the collapsing Almohad empire, a ten-year truce with the Almohads concluded in 1214 enabled Jaime I of Aragón to survive a troubled minority. Acknowledging that the Muslims might attack the young king, Pope Honorius III in 1222 offered full remission of sins to those who came to his aid. Still struggling to make himself master of his realm, Jaime I, however, made no move to undertake a crusade at that time. Indeed, he prohibited Gil García de Azagra, a knight of Santiago, who wished to wage war against the Muslims, from purchasing supplies in Aragón, though the pope admonished him to lift that ban.

Once the truce expired Jaime I, then just seventeen, in April 1225 informed the Curia of Tortosa that “we have assumed the cross to attack the barbarous nations.” Proclaiming the Peace and Truce of God, he asked this assembly of Catalan prelates, nobles, and townsmen to give him aid and counsel “to promote the affair of the cross.” This was the first time that he took the crusader’s cross, but other than Honorius III’s bull just cited, no other concession of crusading indulgences appears to be extant. Although the king did not name his immediate objective, he advanced on Peñíscola, a coastal fortress about thirty miles below Tortosa, in the late summer of 1225. The siege ended in failure, as did his plan to invade the kingdom of Valencia in the following year.

Nevertheless, the prospect of an invasion convinced Abū Zayd, the Muslim king of Valencia, to pay a fifth of his revenue as tribute. Probably hoping to preserve his independence of both Christians and Muslims, he informed the pope that he wished to convert to Christianity and to subject his kingdom to the Holy See. After being expelled from Valencia in 1229 by Zayyān ibn Saʿd ibn Mardanīsh, he met the papal legate, Jean d’Abbeville, and became a Christian; he also pledged homage to Jaime I, who agreed to collaborate against their common enemy, Zayyān. Despite that, Jaime I’s first great military success would not lie in the south but rather in the Balearic Islands.

As Almohad rule disintegrated, the islands, occupied by the Almohads in 1203, regained their independence in 1224. Both Alfonso II and Pedro II had contemplated the conquest of the islands, without, however, mounting an offensive. Catalans, who were just beginning to develop a merchant fleet, viewed the islands as a source of piratical raids on Christian shipping and urged Jaime I to take action against them. When Abū Yaḥyā, the king of Mallorca, rejected his demand for restitution of plunder taken from Catalan ships, Jaime I sought support for an assault from the Catalan Curia generalis of Barcelona in December 1228. In response, Guillem de Montcada, viscount of Béarn, one of the most distinguished Catalan barons, agreed to raise 100 knights, as did Nunyo Sanç, count of Roselló, Cerdanya, and Conflent; the count of Empúries pledged sixty. Archbishop Aspàreg of Tarragona, while excusing himself because of his advanced age, promised 1,000 silver marks, 100 knights, and 1,000 sergeants. Bishop Berenguer de Palou of Barcelona and the bishop of Girona offered 100 knights and thirty knights respectively, while the Abbot of San Feliu de Guixols promised four knights and an armed galley. The towns of Barcelona, Tarragona, and Tortosa pledged to provide ships. While the king proclaimed the Peace and Truce of God, the nobles granted an extraordinary tax, the bovatge, to finance the expedition. Although he had received a bovatge at his accession, as a matter of right, this new levy was freely given. He also acknowledged that the aid which the bishops granted “to subjugate the land and the perfidy of the pagans” was given of their own volition. In return he declared his intention to reward his collaborators.

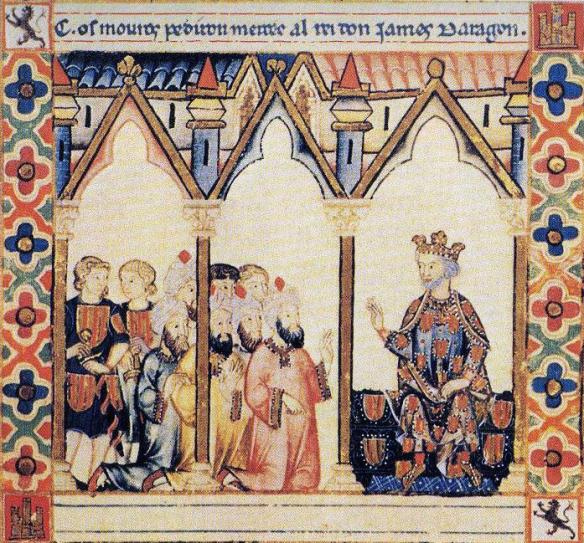

Gregory IX on 12 February 1229 authorized his legate, Jean d’Abbeville, “if an army shall be organized in that region against the Moors,” to “grant the accustomed indulgences.” In the Council of Lleida on 29 March, the legate prohibited the sale to the Muslims of arms and other materials essential to military operations, and condemned anyone who abetted the enemy. He also conferred the crusader’s cross on Jaime I, Bishop Berenguer of Barcelona, and other Catalan clerics and barons, but the Aragonese seem to have held back. They had asked the king to direct the crusade against Valencia, but he refused. The bishop of Barcelona subsequently gave the cross to Guillem de Montcada and other knights. The king renewed his pledge to allot a share in the lands conquered to those participating in the conquest.

After hearing mass and receiving communion, the king and his army of about 800 knights and a few thousand footsoldiers (including prelates, nobles, Templars, Hospitallers, and townsmen) set sail, in a fleet of about 150 ships, from the Catalan ports of Salou, Cambrils, and Tarragona on 5 September. Enroute a great storm came up and the king was urged to turn back, but he declared:

We have undertaken this voyage with faith in God and in quest of those who do not believe in him; and we are going against them for two things: either to convert them or to destroy them, and then to restore that kingdom to the faith of our Lord. And since we are going in His name, we have confidence that He will guide us.

When they encountered another storm as they approached land, he appealed to God, saying: “I am going on this journey to exalt the faith that You have given us and to bring down and destroy those who do not believe in You.”

Three or four days later the fleet reached the bay of Palma; surprisingly the Muslim fleet made no attempt to impede the landing of the crusaders in the port of Santa Ponça, about ten miles from Palma. The bishop of Barcelona proclaimed that “this enterprise . . . is the work of God, not ours; and so those who die in it, die for our Lord and will gain paradise, where they will enjoy everlasting glory. Those who survive will also have glory and honor and will finally come to a good death.” He urged them to “destroy those who deny the name of Jesus Christ,” assuring them that God and his mother would be with them and lead them to victory. After some initial resistance at Monte de Pantaleu and Portopí (where Guillem de Montcada was killed) the crusaders overran much of the island and began the siege of Palma. The Dominican Fray Miguel de Fabra preached to the troops and absolved them of their sins. As the siege dragged on, initial enthusiasm seems to have waned and some apparently thought to return home. To provide continuing support, Gregory IX on 28 November proclaimed the crusade again, instructing the Dominican Ramon de Penyafort and the Dominican prior of Barcelona to preach the indulgence in the French ecclesiastical provinces of Arles and Narbonne.

After attempts to negotiate a settlement failed, Jaime I ordered a full-scale assault on 31 December. Once again the army heard mass and received communion before launching the attack to the cry of “Saint Mary, Saint Mary!” The king reported that a white knight, believed to be St. George, was in the midst of the Christian host. Ibn al-Abbār alleged that 24,000 inhabitants of the town were massacred and that the king of Mallorca (as well as the king of Almería) was captured and died soon after being subjected to torture. Recording the fall of Mallorca, Ibn Abī Zarʿ exclaimed: “May Allāh return it to Islam.”

By Palm Sunday, 31 May 1230, the conquest of Mallorca was completed, although hostile bands were not subdued until two years later. Jaime I returned to the mainland late in the year, but revisited his recent conquest in the following spring in order to repress holdouts in the mountains. Most of the Muslims opted to depart, either for the other islands or North Africa. The king granted franchises to those who would settle there, and inasmuch as most were Catalans the Usatges of Barcelona was established as the fundamental law. The church was endowed, the city of Barcelona was granted commercial rights, and Genoa, Pisa, and Marseille were rewarded with houses and trading privileges. Infante Pedro of Portugal received Mallorca as a fief to be held for life in exchange for his claims to the county of Urgell. During the king’s second visit to Mallorca the Muslims of Menorca recognized him as their sovereign on 17 July 1231, promising an annual tribute and surrendering several strategic castles; but the Catalans did not conquer the island until 1287. After returning to the mainland, Jaime I hastened to defend his conquest in spring of 1232 when he learned that the emir of Tunis was preparing an attempt to recover Mallorca; but the expected assault did not materialize.

Meanwhile, Guillem de Montgrí, the archbishop-elect of Tarragona, and his brother, Berenguer de Santa Eugènia, asked the king to grant them the islands of Ibiza and Formentera in fief; then, after obtaining a bull of crusade from Gregory IX on 24 April 1235, they occupied the islands. The conquest of Mallorca was the first significant step in the development of the Catalan Mediterranean empire.