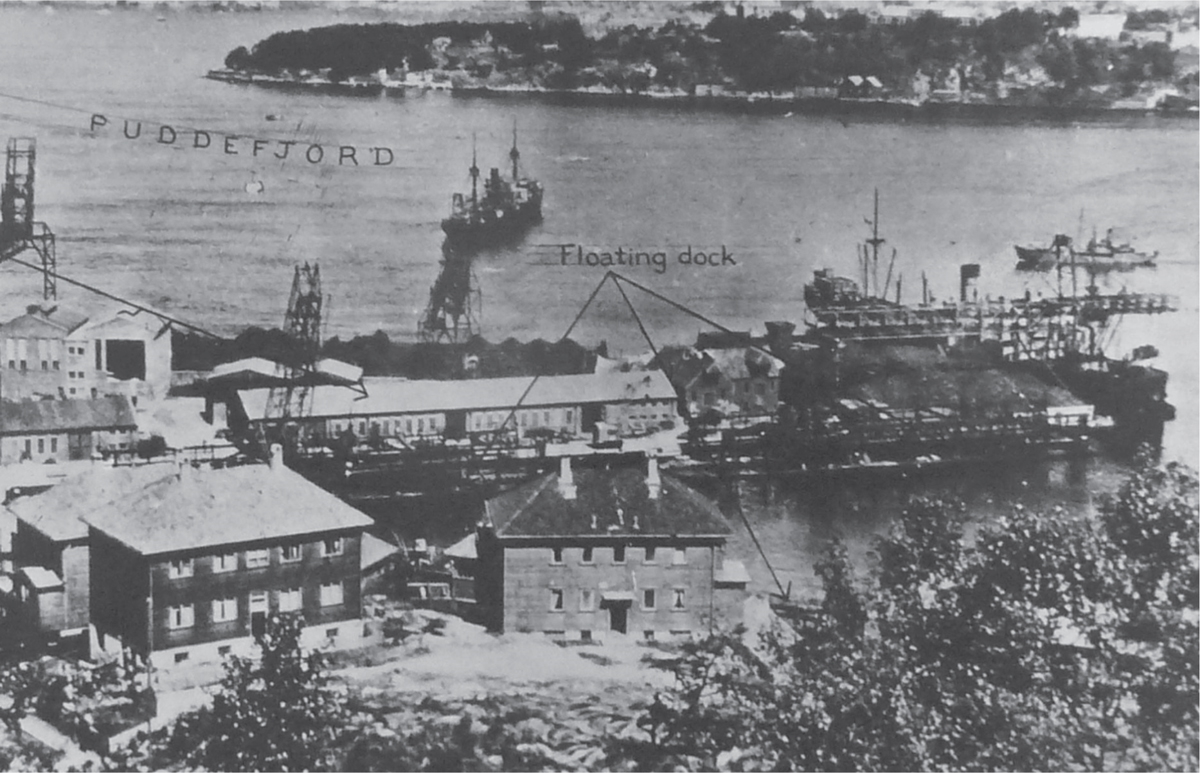

Laksevaag bunker depot, looking north-west, July 1943.

Among the locations in which Welman submersibles were tested was the Queen Mary reservoir at Staines, Surrey.

The plan to sabotage the dock at Bergen, 1943

At the end of November 1943, an audacious raid was made against the German-occupied port of Bergen. The intention was to place explosive charges under the Laksevaag floating dock that supported the Bergen-based U-boats and German ships in the harbour.

The craft

This was the first and only operational use of Welman craft. These were basically one-man-operated submersibles that could carry a removable warhead. According to a wartime report, ‘the operator sat in comparative comfort in the dry, with warm hands and feet and could take food, with the knowledge that if necessary, the craft could be surfaced and the hatch opened eliminating any fear of claustrophobia.’

With an explosive charge attached, they measured just over 20ft long, with a hull diameter of just over 2½ft. Their range was about 30 miles at a maximum speed of around 4 knots, and they could safely dive to 100ft, allowing them to pass under torpedo nets. If necessary, they could stay submerged for some ten hours.

However, one big problem with the design was that they had no periscope. So, to assist with navigation, the craft were fitted with a gyro-compass that was accurate to 10 degrees per hour. Without a periscope, it was necessary for the craft to surface so that the operator could find his bearings through the windscreen and four portholes, or simply open the hatch and look out.

The basic design for the Welman originated from the aptly named Col John Dolphin of the Royal Engineers in mid-1942, and was developed in association with Special Operations Executive’s Professor Dudley Newitt. The idea was that the Welman would be carried by a submarine or flying boat to within 20 miles of its target, before being released to stealthily make its attack, attaching its time-delayed explosive charge to the hull of a ship before escaping undetected.

Three prototypes went into development at SOE’s Station IX, a highly secret facility not far from the town of Welwyn, just north of London; thus the craft was called a Welman (Welwyn One-Man Submarine).

A number of other submersibles were also being developed around the same time, including Chariots, which required operators to sit in diving suits ‘on’ the craft, rather than ‘in it’; and Welfreighters, which were bigger than Welmans and could carry three men inside. There were also the larger three-or four-man X-craft and the very much smaller single-man ‘Sleeping Beauties’ (submersible canoes capable of diving to 40ft). The disadvantage of all these other craft was that they required a bit more training before they could be used. Furthermore, the Welman was generally cheaper and easier to produce than many of the other submersibles.

The plan

The theory of the proposed raid had been tested during trials, when a Welman successfully got past anti-submarine protection, including nets, and placed a dummy charge on HMS Howe. Mock attacks were also practised against HMS Titania, with a dummy charge being successfully placed beneath her.

The 30th Flotilla, manned by officers and men of the Royal Norwegian Navy, were already operating from the Shetlands using motor torpedo boats (MTB) to attack targets in Scandinavian waters, and they agreed to be the first to try the Welmans, with Bergen as the target.

An intelligence report on the port dated 1 November 1943 states that until June 1941, there was only one 500ft-long floating dock at Bergen, which was moored off the end of the jetty at Laksevaag. However, with the development of the U-boat facilities there, more floating docks were provided; as of November 1943, it was reported that there were three 270ft-long and two 350ft-long floating docks in the area.

On 20 November 1943, MTB 635 and MTB 625 left Lunna Voe, Shetland, carrying four Welmans to be used in the raid. The four men undertaking this dangerous mission were Lt Carsten Johnsen of the Royal Norwegian Navy, Lt Bjørn Pedersen of the Norwegian Army, Lt Basil Marris of the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve, and Lt James Holmes of the Royal Navy.

Preparing for the mission

In training, Pedersen had a lucky escape when his craft experienced technical problems and sank in 180ft of water. He escaped and ascended to the surface without any form of breathing apparatus, and was dragged from the water unconscious with blood coming out of his ears, nose and mouth. Fortunately, he was very fit and had good medical attention that saw him recover within a few hours, at which point he apparently asked if he could have another go.

Marris also had a dangerous moment during a Welman trial while being towed at a depth of around 60ft, when water started entering his craft and it reared up vertically. Via a communications line to the surface vessel, he reported that ‘his feet were getting wet’. Hauling the craft to the surface with the extra weight of water presented some difficulties and, while the recovery operation was underway, the communications line came adrift. However, once clear of the water, Marris was able to get out. It was reported that he ‘had his nerves well under control’, although the medical officer in attendance confirmed he was suffering from shock.

The men taking part in the raid were fully aware of just how dangerous the mission would be and were each issued with a handgun, though it is debatable how useful these might prove in the event of trouble. The main concern was simply being able to navigate without being either spotted or heard at the times when they were surfaced.

There were two ways to navigate a Welman. One was to dive the craft and work to a previously calculated formula – a method that was favoured by Holmes, as he did not want to be distracted by any light, landmark or other object of interest. The other method was to remain surfaced and steer via various landmarks and lights, only submerging when a threat was immediately apparent. This was the method chosen by the other three men.

The attack

As planned, the attack on Bergen progressed with the craft being launched from the MTBs at the entrance to the fjord at Solsviksund. The intention was they would make their way first to the island of Hjelthholmen, outside Bergen’s heavily defended harbour. Here, they would camouflage the Welmans and remain in hiding until continuing the raid the following evening. Unfortunately, however, during the day of 21 November, there was a great deal of unexpected activity in the vicinity by Norwegian fishermen that resulted in the Welmans being discovered. It was thus feared the Germans could have received word that some sort of attack was about to happen.

Nevertheless, at approximately 18:45 that day, 2nd Lt Pedersen left Hjelthholmen in his Welman to begin his attack run. He was followed at 15-minute intervals by Lt Holmes, Lt Marris and Lt Johnsen, in that order.

The sea was calm, but fine rain and local fog hampered navigation. Fortunately, Holmes had fitted his craft with a waterproof cape that meant he could sit his Welman low in the water, presenting a smaller silhouette, but when needed he could come to full buoyancy, open the hatch all the way and stand up with a pair of binoculars.

Pedersen, taking the lead, soon observed the tail of a convoy heading into Bergen and kept to starboard of this close to land, avoiding a German watch boat that was signalling the convoy. As he rounded a projecting headland, he suddenly saw a small boat heading straight for him. He immediately dived towards the entrance to Byfjorden and proceeded for some 15 minutes submerged.

Once resurfaced, he expected to see the lights from two lighthouses, but visibility was poor due to the rain on the portholes in the Welman’s small conning tower, and he could only see one light. He therefore opened the hatch and stood up to get a better view. At that moment, he saw the outline of a minesweeper some 40–60 yards away, which was signalling another vessel hundreds of yards away. The signalling immediately stopped and the light was instead directed straight at Pedersen. In a few seconds, other searchlights converged on him.

Before he could even half submerge, shots were fired from a 20mm gun that threw water up around the bows of his Welman. Knowing that the game was up, and fearing that if he were to dive, depth charges would be dropped that could kill both him and his comrades, Pedersen stood up and surrendered, dropping all his papers over the side. Unfortunately, they did not sink and were later recovered by the Germans.

The Welman was taking in water having been hit, though Pedersen later reported that they had apparently not shot directly at him, as at such a short range they could not possibly have missed. To assist in sinking his craft, therefore, Pedersen opened the trim tank flooding valve. As a rubber dingy approached, he opened the main vent and jumped into the water.

The other Welman operators apparently heard the shooting and realized that the Germans would know an attack was in progress and make their defences ready for them. They immediately aborted the mission and turned back.

Johnsen subsequently abandoned his Welman in Hjeltefjorden, near Vindnes, and swam to the shore. Marris, who had struggled with navigating, also made for the shore, abandoning his Welman near Brattholmen. Holmes also came ashore, making his way to Sotra. Assisted by the Norwegian resistance, the three men all met up at Sordalen further up the coast.

The aftermath of the raid

Between November 1943 and February 1944, the three men remained in hiding in Norway, making one abortive attempt to reach the UK by fishing boat in late December. This failed due to extremely bad weather and the poor condition of the boat. Many attempts were also made to recover them by MTBs and submarine chasers from Shetland, but none was successful, until 5 February 1944.

Pedersen, meanwhile, having been taken aboard the minesweeper, was interrogated by the Kriegsmarine the whole night. The next morning, the Gestapo arrived and took him away for further questioning. He had been wearing a Royal Navy volunteer reserve uniform and claimed to be a British officer rather than a member of the Norwegian forces. This was a story he stuck to, as it is thought that he would probably have been executed had the Germans known his true identity.

It was acknowledged by the British authorities later that during the subsequent questioning, Pedersen displayed very marked coolness and presence of mind. He gave such answers that the Germans were completely misled as to the plan of the operation, the number of craft taking part and the arrangements made for the recovery of the officers engaged. He spent the rest of the war in a prison camp in Germany.

Although the raid had not been successful, lessons were learned. Two further submersible raids took place using X-craft, which resulted in the floating dock finally being destroyed in September 1944.

On 2 September 1949, the British Naval Attaché in Oslo contacted the Director of Naval Intelligence informing him that a Welman submarine had been recovered at Bergen. It was agreed that it would be donated to a local museum. It is James Holmes’ Welman that is now on display at the Naval Museum in Horten, Norway.