Following Hannibal’s rapid and stunning victories at the Trebbia, Trasimene, and Cannae, the conflict entered a prolonged and inconclusive phase. For the next thirteen years, from 216 B.C. until 203 B.C., the war settled down to a long period of indecisive maneuvering and intermittent fighting in southern Italy, with each side vying for control of people and resources. It became a period characterized by innumerable assaults and sieges of cities and towns by both sides, with severe retaliatory actions against the civilian populations, whether warranted by their levels of resistance or not. Hannibal moved against any city or town that remained loyal to Rome or even neutral in the conflict. One was either with Hannibal or against him. Those that did come over to him came under intense military, economic, and political pressure from the Romans. Roman reprisals, which were frequent, widespread, and often highly punitive, forced Hannibal to divide and thereby weaken his army to protect as many of his new allies as possible. In areas where Hannibal was not present, the Romans would go on the offensive against towns and cities that had defected, putting considerable pressure on him to come to their aid. With his limited resources, Hannibal simply could not be everywhere at once and in the end, this, probably more than any other reason, may account for his failure to unite the Italians and Greeks of southern Italy and bring the war to a successful conclusion.

During this phase, Hannibal operated in an area of Italy that stretched from just north of Naples to as far south as Rhegium and the Strait of Messina. His army moved across the landscape at will as the Roman legions either followed him at a safe distance in an attempt to wear him down or retaliated against any of the city-states and towns which declared for him. After Cannae, the Romans reverted to a modified form of Fabius’s plan: they tended to minimize direct confrontations with Hannibal, recognizing that while they had the advantage in sheer numbers, they were no match for him when it came to battlefield tactics and the quality of his fighting forces. The armies of both sides ravaged southern Italy—the provinces of Campania, Samnium, Apulia, Lucania (Basilicata), and Bruttium (Calabria). While Hannibal concentrated his efforts on bringing the Greek city-states and the Italian tribes over to his side, the Romans, in response, tried to prevent their defection. Both sides used everything from promises, rewards, bribery, threats, and subterfuge to assaults, sieges, and public executions.

Hannibal needed allies because he had little hope of significant reinforcements from Spain or North Africa. His army was forced to live off the land, and he avoided, for the most part, seeking battlefield victories. He did, however, always welcome a confrontation when an impetuous and overconfident Roman commander was foolish enough to challenge him. Over the next several years, there would be several smaller battles fought in southern Italy, but Hannibal’s major effort was directed to bringing towns and cities into alliance with him through either direct assault or diplomacy.

The Greeks and Italians of southern Italy were often divided among themselves into pro-Roman and pro-Carthaginian factions. In general, the wealthier, aristocratic elements in these towns and cities were pro-Roman, and some even had limited degrees of citizenship because of their close ties with Rome through marriage and financial dealings. At the other extreme were the working classes and the peasants in the countryside, those who had no stake in the status quo and saw in Hannibal a chance for a new beginning. Hannibal promised them freedom from Roman cultural domination and economic oppression, and for those who cooperated, there were additional enticements of a new and more prosperous future. For those who refused or hesitated, punishment could be quick and severe—everything from public beheadings to steaming people to death in the public baths.

The Romans were equally harsh in retaliating against those who left the confederation to join Hannibal. Sections of the countryside between the Adriatic and the Tyrrhenian Seas often became a no-man’s-land, and control depended on which army was passing through at what particular time and how long it stayed. Hannibal could not draw the Roman legions to fight him on open ground, and at the same time he could not protect all the towns and cities that had declared for him. The Romans, on the other hand, could be everywhere at once. Their manpower reserves and economic resources allowed them to go after those who defected with a vengeance. With multiple armies operating in southern Italy at the same time, they could be in more than one place, forcing Hannibal to continually divide and weaken his forces. The Romans focused on supporting their allies who remained loyal against assaults by Hannibal and punishing those who had defected. Both armies laid siege to towns and cities, burned the countryside, and executed those they suspected of collaboration with the other side. The cost in human suffering and economic loss must have been enormous.

The longer the war dragged on, the greater Rome’s chances for victory. Rome had a base of nearly three-quarters of a million men of fighting age to draw upon across Italy, even following the devastating losses in the early battles of the war. The Roman armies had several hundred thousand men under arms doing everything from garrisoning cities allied to Rome to serving in the legions posted throughout Italy, Spain, Sicily, and Sardinia. While the Roman soldiers were not trained and experienced to the level of Hannibal’s mercenaries, there were enough of them that Rome could afford to lose ten for every enemy killed and still win the war. The numbers of the Roman legions increased as the years passed, while Hannibal’s forces gradually diminished, their numbers reduced thorough death, disease, and desertions. In 215 B.C., the Romans were able to put between twelve and fifteen legions in the field; by 212 B.C., that number had increased to twenty-five—amounting to well over one hundred thousand infantry and cavalry.

In southern Italy, the Romans divided their armies and kept to higher ground on the fringes of the Apennine mountain range. They avoided engaging Hannibal on wide, level stretches of land where he could employ his cavalry and elephants to his advantage. Even with Hannibal’s tactical ability, he could not force the Romans onto level ground to fight a decisive battle on his terms. With their multiple smaller armies, the Romans became increasingly aggressive in striking his Greek and Italian allies. Cities under siege or the threat of siege demanded Hannibal come to their aid, and when he could not, confidence in his ability to defeat Rome weakened. Despite Hannibal’s tactical genius, he could not overcome the Roman advantage in manpower and resources. The Romans had the resolve to keep up the struggle against him at any cost and refused to compromise.

The Roman navy effectively blockaded large sections of the Italian coastline, preventing a steady stream of reinforcements from reaching Hannibal. Because of their manpower reserves, the Romans were eventually able to carry the war to Spain and Sicily, even while Hannibal occupied southern Italy. War made the republic stronger; its leaders, both political and military, learned from their mistakes and had plenty of replacements to fill the slots of those captured, wounded, and killed. Rome’s Italian allies in Latium, Umbria, and Etruria remained, for the most part, loyal, providing the manpower, money, and supplies needed to continue the war to a successful conclusion. Hannibal was forced to divide his army into smaller units, placing them under capable commanders and sending them out to protect his new allies. There is little reliable information in the sources on the size and composition of his army during these years in southern Italy, but the core of veterans who left Spain with him in 218 B.C. and crossed the Alps must have been considerably diminished after the battles at the Trebbia, Trasimene, and Cannae, despite the light casualties reported in the ancient sources.

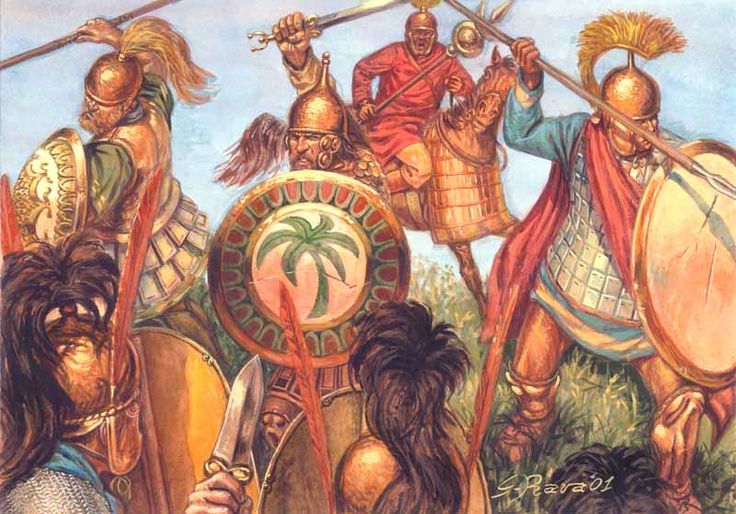

Hannibal’s army was a mixture of soldiers brought together from the corners of the ancient world and fighting for the spoils of war. They spoke different languages, followed different customs, and worshipped different gods—but the common bond that held them together, at least in the beginning, must have been Hannibal’s leadership as well as money. He brought them together, trained them, paid them, and most importantly inspired them to follow him and remain loyal through trying times even when the money was slow in coming. They became unbeatable on the battlefield and remained loyal even as it must have become evident to them, especially in the last few years, that their commander was losing his war. This has come down to us as Hannibal’s most admirable quality and testimony to his ability as a leader. Certainly new recruits must have filled their ranks, coming mostly from the Gauls of northern Italy and the Italians (Brutti) and Greeks of the south. Reinforcements, including elephants, were able to reach Hannibal from North Africa on at least one occasion, arriving on the southern Adriatic coast at Locri.

Southern Italy and the eastern part of the island of Sicily were collectively known as Magna Graecia or Greater Greece. They had been colonized by Greeks looking for fertile land and economic opportunities as early as the eighth century B.C. Campania and Apulia were among the most fertile of these areas and contained some of the most prosperous cities in Italy. Campania occupied a narrow zone between the Tyrrhenian Sea on the western coast of Italy and the Apennine Mountains. According to the ancient sources, the province surpassed all others in terms of its natural resources, and even in ancient times it was a favored holiday resort for Romans because the summer heat was tempered by a brisk sea breeze. The natural wealth of the area could, in large part, be attributed to Mont Vesuvius, which over millennia had layered the land with a rich coating of phosphorus and potash. Campania became a center of olive and grape production, and its wines, including the dry and strong Falernian (sherry), were exported throughout the Mediterranean world.

Among the most important cities along the western coast of the province were Cumae, the oldest of the Greek colonies; Neapolis (Naples), a major port; and Capua, which had been founded by the Etruscans in the late sixth century B.C. and was the wealthiest of the three. While these cities were tied to Rome by treaty, each one retained its own language, form of government, and laws. There were several Greek cities on the eastern seaboard of southern Italy that were also prosperous: Crotone, Petelia, Sybaris, Heraclea, Metapontum, and Tarentum. Sybaris, like Capua, had a reputation for luxury and wealth, and Crotone had been the home of the mathematician Pythagoras and long a center of culture, medicine, and science. Tarentum (Taranto) initially had been a Spartan colony with the best natural harbor on the eastern coast of Italy. Though prosperous and culturally advanced, the cities on both coasts never joined together to form a unified political entity. They alternated between periods of cooperation and rivalry, often forming temporary political and economic networks, but all the while remaining fiercely independent as city-states, each one loosely connected by culture to its founding city on the Greek mainland. Some of these cities saw in Hannibal an opportunity to contain if not stifle the influence and control Rome was coming to establish over southern Italy and an opportunity to play one side off against the other. They would negotiate with Rome and Hannibal, looking for the best deal and then switching sides as events and changes of fortune warranted—something which proved to be a dangerous gambit and often led to the destruction of those who played it.

The interior portions of southern Italy were a world apart from the coastal regions. They were largely undeveloped and inhabited mostly by Italian tribes and clans, among them the Lucanians and the Brutti—a more primitive and considerably less prosperous people. Over the centuries, they came, to varying degrees, under the cultural influence of their Greek neighbors, and some of them adopted Greek styles of architecture, art, religion, and even language. Traveling today through southern Italy, especially along the Adriatic coast, it is easy to see why Hannibal focused on this area. The ruins of Greek towns and cities line the coast and the terrain tends to be flat, wide, and fertile. The lay of the land would have made moving and feeding an army much easier than in the mountainous areas of central and western Italy. In addition, southern Italy was much closer to North Africa by sea, and, along with Sicily, would have made a natural extension to a restored maritime empire for Carthage. At one point Hannibal apparently considered having his army dig a canal across the narrow and most southern section of the peninsula to isolate it from the mainland.

Immediately after Hannibal’s victory at Cannae, some of the Greek cities and towns in the area around the battlefield began to defect. The Apulian towns of Salapia (Manfredonia), Arpi (whose ruins are just northeast of modern Foggia), and Herdonia (just south of Foggia, off the autostrada, at the small town of Orta Nova) left the Roman confederation when Hannibal offered them treaties of friendship with Carthage and freedom from Roman taxation and cultural oppression. They were promised there would be no obligation for military service and that they could live in a prosperous new Italy with mutually beneficial economic ties to Carthage. Hannibal utilized the rhetoric of popular liberation and self-determination. He exploited the political factions within those cities to his own advantage as he cut deals and offered financial and military support to whichever factions could be of use to him in his struggle against Rome. His promises resonated with the impoverished—the working classes in the cities and the peasants in the countryside. But in general, the wealthy aristocratic elements in the cities rejected his call because they were tied to Rome through marriage alliances and economic arrangements that were more profitable and stable.

From Cannae, Hannibal moved his army west and occupied the town of Compsa (Conza della Campania), which lay on the boundary between the provinces of Lucania (Basilicata) and Campania. Its leadership was divided between two mutually hostile clans, the Hirpini and the Mopsi. The Hirpini supported Hannibal and with his help drove out the pro-Roman and aristocratic Mopsi. Hannibal garrisoned the town, using it to store his army’s baggage and the massive amount of valuables and weapons taken at Cannae. Scenarios like what occurred at Compsa began to play out in other cities and towns in southern Italy as well. In Salapia, one of the leaders, Dasius, betrayed the city to Hannibal in return for his help in driving out a pro-Roman faction led by one of his rivals.

At Compsa, Hannibal divided his army into three groups. He sent one group south into Lucania and Bruttium under the command of his younger brother Mago, his nephew Hanno, and another of his principal commanders, Himilco. The Bruttians would prove to be fertile ground for recruitment as they had long resented the Romans and at the same time were envious of the prosperous Greek city-states along the Adriatic coast. By joining Hannibal, they saw an opportunity to remove the Roman yoke and at the same time profit by plundering any Greek cities that resisted joining him as allies. Mago, Hanno, and Himilco further divided their forces and Himilco undertook to lay siege to Petelia (Strongoli), a Greek city on the coast. The Petelians were among the most loyal of Rome’s allies and they held out for nearly a year, until the siege brought them to a state of starvation, reducing them to eating leather, grass, and tree bark. The defenders managed to send a desperate plea for help to Rome, but the reply was that given their remote and isolated location in the extreme south, they were on their own. Still, the Petelians fought to the last, and when the city was taken, Himilco gave it over to the Bruttians to plunder. Most of its people were killed, and those who survived were sold into slavery.

Using Petelia as an example of what would befall those who rejected an offer of alliance with Hannibal, Mago negotiated agreements with other Greek cities along the southern Adriatic coast and assaulted those that refused or even hesitated. After a short stay in Bruttium, Mago left by ship for Carthage, probably from the port of Locri on the extreme southern tip of Italy, to carry the news of Hannibal’s victory at Cannae and ask the senate for reinforcements and money to continue the war. Hanno and Himilco remained in the area and continued to lay siege to towns and recruit new soldiers.

Hannibal left Compsa with his main force and moved once again into the province of Campania to secure a port on the Tyrrhenian Sea. The area around Neapolis constituted a defensive line of fortified cities allied with Rome; among the most prominent were Capua, Acerrae, Suessula, Cumae, Nola, Nuceria, and Casilinum. They were tied together by the Roman highway, the Via Latina, and protected for Rome what was probably her most valuable agricultural region. The area had an accessible coastline with several important ports in addition to Neapolis; the most notable being Cumae (just twelve miles west of Naples) and Puteoli (modern-day Pozzuoli, just a few miles south of Naples). This was Hannibal’s second incursion into Campania following his spectacular night-time escape out of the valley using cattle with firebrands tied to their horns.

Neapolis was the prize that Hannibal sought initially. The city had been founded by the Greeks in the sixth century B.C., and its name translates as “the new city.” A base there would make for shorter and quicker communication lines with Carthage and provide easier access to reinforcements and supplies from North Africa and Spain. Carthage to Neapolis is a distance of 313 nautical miles. With favorable winds and relatively calm seas, it could be crossed in ancient times in three or at most four days. The voyage from Neapolis would avoid a longer and more treacherous passage from the Adriatic side of Italy and around the often stormy and dangerous southeastern coast of Sicily. When Hannibal arrived and saw the massive fortifications and the sizable Roman garrison protecting the city, he abandoned any idea of a siege and turned his attention to the smaller city of Capua just a few miles to the north.

If he could not take Neapolis, then Capua was Hannibal’s second choice. It was one of the largest cities in Italy at the time and very wealthy. According to the ancient sources, its people had been corrupted by the “excesses of democracy” and they set no limit when it came to luxury. Capua, by Roman standards of morality and civic duty, was corrupt because its people had enjoyed so many decades of freedom, they had lost any sense of restraint and discipline. Their wealth was so great that they had access to more than they could possibly want and enjoy. This portrayal of Capua reflects a traditional Roman republican belief that unbridled freedom and extravagance are the ruination of a people. For the Romans of the early republic, what was most desirable was a society of people who were simple living, patriotic, civic minded, religious, and morally upright. That view would change radically following the end of the war with Hannibal, as Rome transitioned from a simple republic to a wealthy empire in the century following.

Capua willingly went over to Hannibal and in so doing provided him with an arsenal of some of the best-quality weapons available in the ancient world. The city was a prosperous manufacturing center which, in addition to making armaments and glass, excelled in the production of perfume. The perfume market or seplasia at Capua was recently excavated, and its remains support literary references to the ancient inhabitants’ love of luxury. Another indicator of Capua’s wealth are hoards of coins that have been found and dated to the period of Hannibal’s occupation, 216–211 B.C. The city also produced finished metalwares from iron and copper that were exported all over the ancient world—even as far as Scotland.

Hannibal had demonstrated to the people of Capua that he could annihilate Roman armies on the battlefield, and he promised them, in return for joining him early on in his campaign, a prominent place in the new Italy he was creating. He assured the leaders that their city would become the legal and commercial center of a new confederation of Italian and Greek city-states, and that at the end of the war he would return the Ager Falernus, the fertile river valley that had been taken from them by Rome two centuries before.

The leaders of Capua were clever businessmen and intended to play both sides against the middle to negotiate the best deal for themselves. Before coming to terms with Hannibal, they sent a delegation to the Roman consul at nearby Venusia (Venosa, not far from Compsa), indicating they were open to considering any inducements he might be inclined to offer them to remain within the confederation. In response, the consul reminded the envoys of their city’s long association with Rome, the prosperity that had come their way as a result, and the Roman expectation that Capua would honor its prior commitments by contributing men and money in the fight against Hannibal.

The delegation returned to Capua and reported the consul’s response to the senate. The senate circumvented the consul, going over his head and sending emissaries directly to Rome to seek a better deal. The emissaries demanded, as a condition of remaining an ally, that one of the two annually elected Roman consuls had to come from Capua. The consuls were the highest executive officers in Rome, and not only did they command Roman armies in time of war, but they administered the state. They were second only to the dictator in their power. Rome rejected the demand out of hand and ordered the envoys to leave the city before sundown. The senate at Capua then sent a delegation to Hannibal, who quickly agreed to everything they asked. To seal the deal, Hannibal assured them Capua would become the most powerful and prosperous city in Italy once the war ended.

Despite Hannibal’s promises, the delegation demanded carefully delineated terms as the price for their defection. First, they required that no citizen of theirs would be obliged to serve with Hannibal’s army against his will, and second, that Capua would retain its own form of government and laws free from Carthaginian interference or oversight. As a final inducement, Hannibal agreed to exchange three hundred of his most prized Roman captives for an equal number of young men from the aristocratic families of Capua who were serving with the Roman cavalry in Sicily at the time. While these young men were serving officially as Roman auxiliaries, there is some doubt that their service was entirely voluntary. They might well have been kept as hostages to insure the loyalty of their city to Rome.