Former governor William Tryon and other Tory leaders confirmed the island’s loyalty when they met with General Howe aboard the Greyhound immediately after he arrived.

Tryon painted a picture of extensive Loyalist support throughout the region. He predicted that the king’s faithful would supply Howe with whatever he needed, particularly men. “I have the satisfaction to inform your Lordship,” Howe wrote to Germain, “that there is great reason to expect a numerous body of inhabitants to join the army from the provinces of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, who in this time of universal apprehension only wait for opportunities to give proofs of their loyalty and zeal for government.”

Tryon urged Howe to attack Washington immediately. The governor was already doing all he could to organize clandestine resistance in the city and surrounding counties. Working with prominent Loyalists like Oliver De Lancey, Tryon was planning an uprising within the city to coordinate with Howe’s invasion. He even hoped to capture or assassinate General Washington. One of Tryon’s men, Thomas Hickey (posing as a British deserter), succeeded in joining Washington’s bodyguards and was about to capture or kill him when he was discovered on June 20. Hickey was tried and hanged eight days later in front of a crowd of soldiers and irate New Yorkers.

Washington moved fast to counter Tryon’s efforts. He urged the New York Provincial Convention (the patriot governing body) to remove from Manhattan “all persons of known disaffection and enmity to the cause of America.” The convention responded forcefully, rounding up prominent Tories, including former mayor David Matthews, and imprisoning them in Litchfield, Connecticut, and other places. Oliver De Lancey narrowly escaped capture by jumping into a rowboat in the dead of night and pulling for the battleship Asia, conveniently anchored in the Upper Bay on high alert.

The aggressive Tryon was not discouraged; he continued calling for immediate action, arguing that the rebels would offer little resistance. Howe’s splendid army mesmerized him and warmed his heart. He had been hoping for a stupendous display of British power ever since he lost control of the city and province the previous year. By the fall of 1775 his political power had deteriorated to the point where he almost landed in jail. On October 19 an aide warned him that Congress had ordered his arrest. Tryon reacted quickly, fleeing in the middle of the night with his family to the packet Halifax and then to the larger British transport Duchess of Gordon.

The 64-gun Asia, under Captain George Vandeput, and the 44-gun Phoenix (Hyde Parker Jr.) protected Tryon. The Asia had been in New York since May 26, 1775, and the Phoenix since the middle of December. Vice Admiral Samuel Graves had dispatched the Asia from Boston in response to an urgent request from then royal lieutenant governor Cadwallader Colden, who desperately needed protection from New York’s rebels. Growing in numbers and confidence, inspired by victories at Lexington and Concord and at Fort Ticonderoga, the patriots were in effective control of the city.

The Asia’s guns had a calming effect. Captain Vandeput worked out a modus vivendi with the rebels. Fearing the battleship’s guns, they supplied him with provisions and even allowed him to peacefully evacuate the tiny contingent of redcoats left in Fort George, at the southern tip of Manhattan. Vandeput wanted to put a stop to the garrison’s growing number of desertions.

When Washington arrived in the city in April he put a quick stop to trafficking with the warships, but they remained in the harbor, a constant threat, and a reminder of how weak the patriots were on the water. Vandeput had no trouble obtaining supplies from the surrounding countryside, where he was quietly supplying arms to Loyalists engaged in a vicious civil war for control of their counties.

On July 12, 1776, only hours before Lord Howe’s grand entrance into New York Harbor, Admiral Shuldham, who had no idea when Howe would arrive, ordered two of his best captains to make a run up the Hudson to Haverstraw Bay, thirty-five miles north of Manhattan, to test rebel defenses along the way. Shuldham wasn’t anxious to do it. He didn’t like risking men-of-war and their crews in this way. They could not be replaced and would be needed shortly in the invasion that was about to take place, but General Howe was insisting. Since control of the Hudson was such a vital part of the king’s overall strategy, he wanted some idea of how strong the defenses were as soon as possible.

A run to Haverstraw Bay seemed a good way to find out. Five miles long and three and a half wide, the bay, near present-day Croton Point Park, was the widest part of the Hudson. Howe thought warships could anchor there, reasonably safe from attacks by land or water. He wanted to block the movement of supplies and men from the northern colonies to Washington in Manhattan, and prepare the way for an amphibious assault on the Highlands. He never anticipated that he would also be demonstrating why gaining command of the Hudson, never mind the entire corridor to Canada, was illusory.

Ever since Washington had arrived in New York in April he had been working on the Hudson’s defenses, lining the New Jersey and New York shores with fortified batteries, and erecting two forts facing each other across the river—Fort Constitution (later renamed Fort Lee in honor of the general) and Fort Washington. Large obstructions were sunk between the two forts to slow any vessel attempting to run by so that gunners could get a good shot at them.

Colonel Rufus Putnam, acting chief engineer of the Continental army, was in charge of constructing the forts and placing obstructions in the river. He built Fort Washington on Manhattan’s highest point, a rocky, 230-foot-high cliff north and west of Harlem Heights, and placed Fort Constitution opposite it on the New Jersey side, 3,300 feet from Jeffrey’s Hook, a tiny point of land jutting out into the river below Fort Washington. By the first week in July, Colonel Putnam had Fort Washington up and running, and he had begun Fort Constitution, but neither the fort nor the obstructions were far advanced when Shuldham tested them.

At 3:00 p.m. on the twelfth, the 44-gun Phoenix (Captain Hyde Parker Jr.), the 20-gun Rose (Captain James Wallace), and three tenders, Tryal, Shuldham, and Charlotta, pulled their hooks, left their anchorage off Staten Island, and raced north toward the Hudson with a favorable southerly wind and a strong incoming tidal current. Their sudden movement created panic in the city. People assumed that this was the start of a major assault. Their hysteria subsided only when it became clear that just two warships and their tenders were on the move. When they sped by, batteries on Red Hook, Governors Island, Paulus Hook, and the city peppered them. Smoke and the smell of gunpowder filled the air, but the warships kept moving.

As they swept upriver, returning fire as they went, they soon approached Fort Washington, and raced by it with no problem. The fort’s fire cut them up some, but not enough to even slow them down. Total casualties aboard from all the cannonading were three men wounded. The American gunners suffered far more. Several inexperienced artillerists were killed or wounded when their cannon burst due to insufficient swabbing.

As the men-of-war sailed beyond Fort Washington, batteries on the woody heights of Westchester County fired on them for eleven miles with no effect. Nothing stopped their progress upriver. Eventually they anchored in Tappan Bay and then moved farther north to Haverstraw Bay with no opposition.

When Washington heard that men-of-war had broken through his defenses as if they were cobwebs, he became determined to improve them. He told his brother John Augustine that the ships exhibited “proof of what I had long religiously believed; and that is, that a vessel, with a brisk wind and strong tide, cannot, unless by a chance shot, be stopped by a battery, unless you can place some obstruction in the water to impede her motion within reach of her guns…. They now, with their three tenders … lie up … Hudson’s River, about forty miles above this place, and have totally cut off all communication, by water, between this city and Albany, and between this army and ours upon the lakes…. Their ships … are … safely moored in a broad part of the river, out of reach of shot from either shore.”

Preventing passage of enemy ships upriver was a high priority for Washington. No one believed more firmly in the importance of denying Britain control of the Hudson than he did. Time and again, he described the river as “of infinite importance.” “Almost all our surplus of flour and no inconsiderable part of our meat are drawn from the states westward of Hudson’s River,” he explained. “This renders a secure communication across that river indispensably necessary…. The enemy, being masters of that navigation, would interrupt this essential intercourse between the states.”

Washington never doubted that if left unchecked, the British would dominate the Hudson and cut off New England from the rest of the country. He held this view while demonstrating, over and over, that they had not done so as yet, by continuously crossing with troops and supplies. In fact, throughout the long war, he and his subordinates were never prevented from crossing, and only on rare occasions were they even inconvenienced.

In order for the British to actually command the river, the political support of the countryside was essential, and if they had had that, there would have been no need for a revolution in the first place. Lack of political support along important stretches of the Hudson meant that warships would be subject to guerrilla-style attacks, as would the guard boats they would be forced to run alongside their big ships, not just to protect against the patriots but to impede desertion.

Rebel fireships would be a constant problem, as would row galleys and other small vessels darting out from tiny creeks, inlets, harbors, and rivers—places ships of the Royal Navy could not reach, even with their smaller vessels. Going after patriot guerrillas in unfamiliar creeks using ship’s boats and galleys would be asking for trouble. Transports bringing food and other vital supplies to sustain the warships would be subject to attack as well. Food and water, not to mention liquor, would be impossible to obtain from a hostile countryside.

In spite of the gloomy report to his brother, Washington did not sit idly by; he attacked. With help from the New York Provincial Convention, he rushed to complete Fort Constitution and the obstructions in the river. He was counting on the obstructions to slow down the Phoenix and the Rose on their return downriver, as well as handicap any other men-of-war or transports attempting trips upriver. While General Mercer worked on Fort Constitution, Colonel Putnam sank more old ship hulks and chevaux-de-frise between the forts. Washington had high hopes for the chevaux-de-frise—huge, sharp, wooden stakes with iron tips. Putnam built them in Brooklyn and floated them over to the Hudson.

While Washington was making these preparations, he was also trying to figure out what the Phoenix and the Rose were up to. They might be carrying weapons to Loyalists for an attack on the Highland forts, Montgomery and Clinton, which were incomplete and weakly manned. They might also intend to destroy the two Continental frigates being built at Poughkeepsie, the Montgomery and the Congress. They would certainly be making detailed charts of the river, and laying down guides to navigation up to the Highlands and beyond for a future amphibious thrust to Albany.

Whatever they were doing, Washington was determined to give them plenty of trouble. He urged the New York Convention to improve the incomplete Highland forts, and he placed his troops at Fort Washington on Manhattan and at Kings Bridge on alert. He also sent an urgent message to Brigadier General George Clinton in New Windsor. Clinton had just returned from Philadelphia for the vote on the Declaration of Independence. In addition to being a member of Congress, he was a brigadier general of militia and a leader in Ulster and Orange counties—both staunchly patriot.

Washington told Clinton to be prepared for an “insurrection of your own Tories,” aided by the warships and their tenders. He urged him to seek aid from Connecticut governor Jonathan Trumbull if he had to.

The politically astute Clinton was a step ahead of Washington. He already knew about the warships and was busy gathering as large a force as possible to counter them. And he was watching for Loyalists in his counties cooperating with them. He even had men guarding against a possible Indian attack.

Clinton’s brother, Colonel James Clinton, had sounded alarm guns the minute he heard about the warships. He also put Forts Montgomery and Clinton on alert. They were located just north of Bear Mountain on the west side of the Hudson on either side of Popolopen Creek.

The whole countryside had swung into action. Hundreds of militiamen turned out. General Clinton assigned one regiment to Fort Constitution, another to Fort Montgomery, and a third to Newburgh, just north of the Highlands. Every other regiment was placed on high alert. General Clinton urged boat owners on the west side of the Hudson to be ready to move troops, and those on the east side to form a barrier of boats, stretching across the Hudson at Fort Constitution. If necessary, he planned to set the boats on fire to stop the warships from sailing north through the winding, fifteen-mile-long Highland passage running between Peekskill and Newburgh. Clinton gave orders to destroy any boat liable to fall into British hands. He also ordered the carpenters building the Continental frigates at Poughkeepsie to make fire rafts out of vessels seized from Tories and stored at Esopus and Kingston.

The fast response of New York’s yeomanry acted as a tonic for Washington, who had been dealing for weeks with citizens of a much different political stripe. It was nice to see that the revolution had plenty of adherents in the counties up north. It demonstrated better than anything else that attempting to control the Hudson without the political support of the countryside was a hopeless endeavor.

William Smith, the prominent Tory lawyer, could not understand why the warships did not have plenty of marines on board to harass the patriots, as if they could possibly do anything other than get themselves and their Loyalist allies slaughtered. Smith had no idea how many men General Clinton had at his command.

The enemy frigates kept in touch with Lord Howe’s fleet anchored off the east side of Staten Island by sending a whaleboat with a petty officer and six men running downriver. Shore batteries fired on them and sometimes hit them but did not stop them. Food and supplies were another matter. New York patriots made it impossible for the warships to get them from the countryside. One of the first things Captain Hyde Parker Jr. did was dispatch a squad from the Phoenix to take cattle from nearby fields, but the patriots were ready and drove them off. The cattle were then moved inland beyond the reach of the ships.

In their clumsy attempts to seize food and other provisions, the British created more enemies. On July 16, Captain Wallace sent men from the Rose to raid the farm of Jacob Halstead, a half-blind farmer whose land ran down to the water. Wallace’s men burned Halstead’s meager barn and house and stole his few pigs. News of the incident soon spread, creating a strong backlash. Vicious attacks were typical of Wallace, who had the same mind-set as Lords Sandwich and Germain. He had been harassing Rhode Island for months before moving to New York. His behavior was applauded in London, as he knew it would be.

Washington wanted to attack the warships, but his resources were pathetically few. The Continental navy, which might have played an important part in protecting the Hudson, was nowhere to be found. Even though a decisive battle that might determine the outcome of the war was about to be fought in places where naval support was critical, no ships of the American navy were taking part. Washington certainly needed them, and so did Benedict Arnold and Generals Schuyler and Gates on Lake Champlain.

The absence of the patriot navy was the fault of the amateur warriors in Congress who established the Continental navy in the fall of 1775. They created the wrong kind. They opted for building a poor, indeed laughable (if it hadn’t been so serious), imitation of the Royal Navy, when they could have looked to the fleet of row galleys that Benjamin Franklin and his colleagues built in the summer of 1775 to defend Philadelphia and the Delaware River. Franklin’s galleys were far from the glamorous frigates Congress found so appealing. The galleys were fifty feet long and eighteen feet wide, with flat bottoms, and carried a single cannon of between twelve and thirty-two pounds in the prow. Powered by twenty oars and two lateen sails, they were ideal for maneuvering in shallow river waters, strong currents, and bad weather. A flotilla of these boats could be a formidable force against His Majesty’s frigates on the Hudson and in the East River, Hell Gate, and Spuyten Duyvil Creek, as well as on Lake Champlain.

The Congress had no interest in this type of craft, however. Members wanted to build frigates and sail of the line. They put their money and energy into constructing a small squadron of frigates that could do very little against the Royal Navy. If Continental frigates had been available in New York, Admiral Howe would easily have captured them and used them against the patriots.

Not only did Congress build the wrong type of fleet, it appointed the wrong individual to lead it—Esek Hopkins, of Providence, Rhode Island. When he was appointed, in December 1775, Congress expected him to be Washington’s naval counterpart. Members envisioned him working closely with Washington, especially in the defense of New York. Instead, Hopkins, who was soon censured by Congress, remained idle in Providence the entire time Washington was fighting to defend Manhattan. Even if Hopkins had been a seagoing Washington, however, he still would not have been of much use. He would not have had the right type of warships.

The Continental navy had a number of outstanding fighters, among them John Paul Jones, John Barry, John Manley, Lambert Wickes, Nicholas Biddle, Joshua Barney, Samuel Tucker, Hoysted Hacker, Silas Talbot, Seth Harding, and Charles Alexander. They could have been of signal importance in defending New York, but they were employed elsewhere on inconsequential missions like commerce raiding, which hundreds of privateers were doing far more effectively.

The burden of fighting on the water around New York fell to an army lieutenant colonel, Benjamin Tupper. He had impressed Washington the previous year with his guerrilla-style attacks in Boston Harbor. Tupper’s activity in Boston, small though it was, actually rattled Vice Admiral Samuel Graves. Graves knew that if Tupper had been given sufficient resources he would have threatened the largest British warships anchored in the harbor. Unfortunately, Congress did not appreciate Tupper or even seem to know about him. But Washington did. He liked Tupper’s aggressive small boat tactics and appointed him head of his small naval force in New York.

Washington also employed David Bushnell’s submarine against Lord Howe’s flagship Eagle, but the attempt failed. Had it succeeded, which it almost did, Congress might have paid some attention and rethought the composition of the navy. But since it failed, its possibilities were ignored. Bushnell was a gifted Connecticut inventor from Saybrook. He had constructed a single-man submarine that actually worked and caught the attention of Benjamin Franklin, who was racking his brain in 1775 trying to figure out how to defend the Delaware River. Franklin recommended Bushnell to Washington, who saw him in Boston and was impressed. He would have used the submarine then, but it was too late in the season.

Bushnell brought his invention to New York, and on September 6, 1776, Washington allowed him to try it out. The Turtle, as it was called because of its peculiar shape, performed well that day and got close enough submerged to almost plant an underwater bomb, which Bushnell had also invented, on the Eagle’s hull. At the last minute it struck metal and would not attach, ruining the attempt. Bushnell came very close, however. He made a second attempt on a frigate, but for a variety of reasons that did not work either, and the whole project was given up.

Colonel Tupper, meanwhile, used the few resources at his command to courageously attack the Phoenix, the Rose, and their three tenders. He had only five small row galleys with a single cannon in their prows. His flagship, Washington, had a 32-pounder; the rest had similar armament. With only five guns Tupper could not possibly do much harm to the big warships. Nonetheless, on August 2 he bravely tried, running close enough to inflict minor damage, shooting for a remarkable hour and a half before being forced to retreat.

He tried again on August 16 with six row galleys and had the same results. He roughed up the warships but did not actually threaten them. Tupper also attacked the frigates and their tenders with fireships, but again, the attacks were on too small a scale to have a great effect. They did succeed in burning the tender Charlotta on August 16. A six-pound cannon, three smaller ones, and ten swivels were salvaged from her charred remains.

Tupper’s effort was a heroic but futile gesture. At the same time, it was instructive. If he had had a large fleet of galleys and far more fireships, which he might have had if Congress had allotted its resources differently, he would have been a real problem for the British.

Three days before the Howes launched their long-awaited attack on New York, the Phoenix and the Rose returned with their surviving tenders to Staten Island—recalled to participate in the invasion of Long Island. After the last of the fireship attacks, on the seventeenth they moved down to Tappan Bay. On the eighteenth, in the dead of night, they pulled their anchors and, taking advantage of wind and tide, sped downriver, bracing for underwater obstacles and concentrated fire from Forts Constitution and Washington.

The wind was blowing hard and a heavy rain falling. When they came to the line of river obstructions, they breezed through them once more. Cannon in the two big forts and near the city fired away without effect. By ten o’clock in the morning the warships and their tenders dropped their hooks off Staten Island, having sustained little damage. The Rose had two wounded and the Phoenix none. It was a complete defeat for Washington’s river defense, although he refused to recognize it.

Washington explained what had happened to Governor Trumbull of Connecticut. “On the night of the 16th, two of our fire vessels attempted to burn the ships of war up the river…. The only damage the enemy sustained was the destruction of one tender. It is agreed on all hands, that our people … behaved with great resolution and intrepidity. One of the captains, Thomas, it is to be feared, perished in the attempt or in making his escape by swimming, as he has not been heard of…. Though this enterprise did not succeed to our wishes, I incline to think it alarmed the enemy greatly.”

Although the Phoenix and the Rose made a mockery of Washington’s river defense, they did not prove that the British could control the river. The continuous attacks on them in Haverstraw Bay and the Tappan Zee showed that control of the Hudson wasn’t possible when rebels dominated an aroused countryside. Admiral Shuldham reported to the Admiralty that the expedition had actually been “fruitless.”

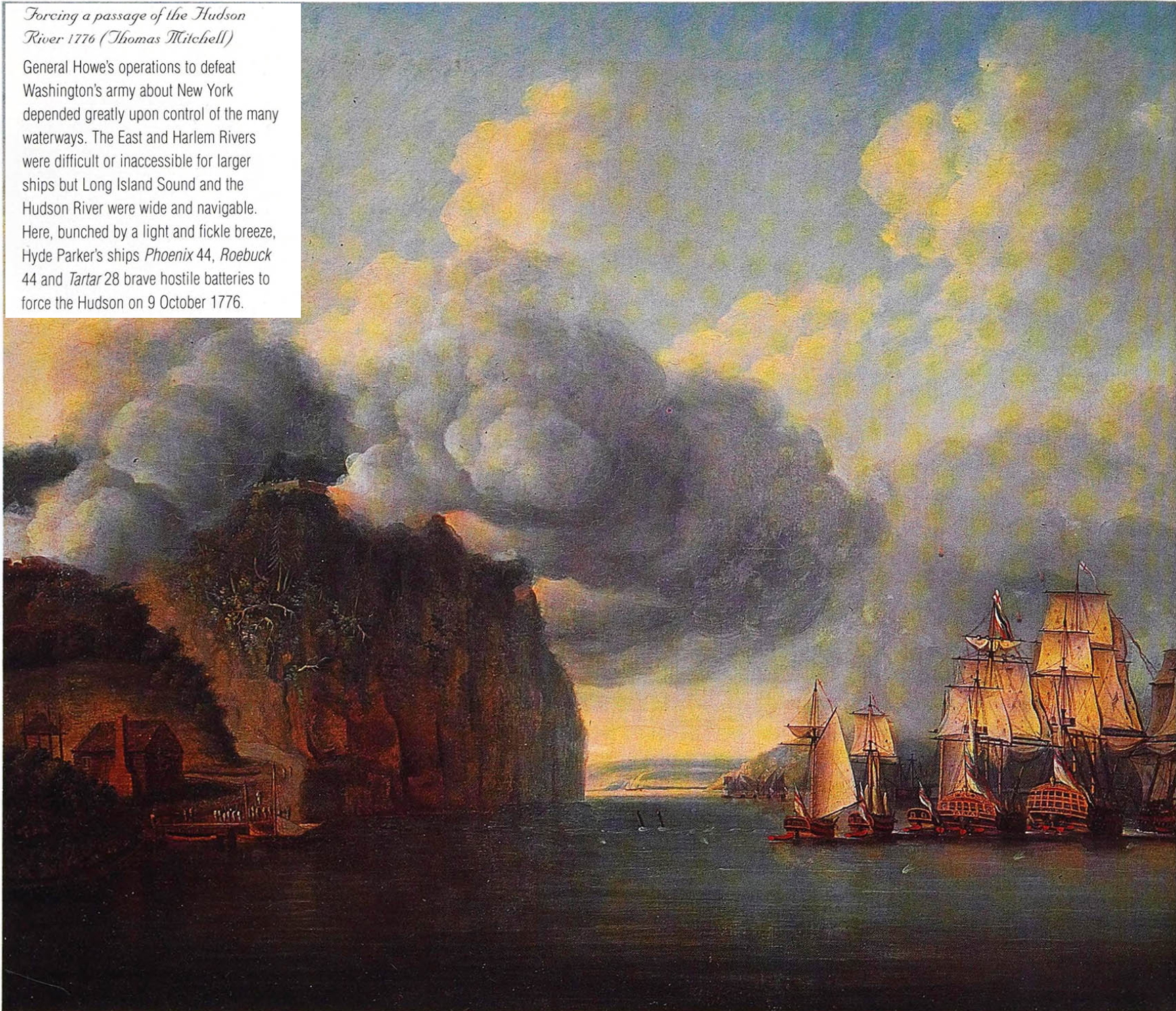

On October 9, the heavy frigates Phoenix and Roebuck, the sloop of war Tartar, and three tenders raced up the Hudson from Bloomingdale toward Forts Washington and Lee and the enhanced river obstructions. The ships were well barricaded on their sides against small-arms fire. Captain Hyde Parker Jr. led the way in the Phoenix, remaining close to the east side of the river, its deepest part.

The forts were alerted and ready, firing as the men-of-war sped by, damaging sails, rigging, masts, spars, and ship’s boats while killing nine and wounding eighteen. Several shots pierced the ships’ hulls, but nothing stopped them. They continued north, attacking Colonel Tupper’s small fleet of row galleys and other vessels in Spuyten Duyvil Creek, capturing some, and sinking others. Tupper’s men beached their boats when they could and ran. When they could not, they leaped overboard and swam for shore. After the one-sided melee was over, the men-of-war settled in Tappan Bay for repairs and to bury their dead. Hyde Parker Jr. had once again demonstrated the inadequacy of the river defenses, and also the Howes’ ability to easily land troops in Washington’s rear.

Although Washington’s defenses inflicted more damage this time, they failed in the main task of blocking the river. Nonetheless, Washington continued to have confidence in the forts and obstructions and kept adding to them.

Three days later, with all possible opposition on the water removed, General Howe began his long-delayed push to induce Washington to evacuate Manhattan. Nearly thirty critical days had elapsed since the landing at Kip’s Bay, and winter was fast approaching. It looked as if the king’s objective of crushing the American rebels in a single season was now completely beyond reach. Howe had already written to Germain on September 25 telling him that achieving victory by the end of the year was impossible. “I have not the slightest prospect of finishing the contest this campaign,” he wrote, “nor until the rebels see preparations in the spring that may preclude all thoughts of further resistance.”

Although Howe’s armada had been extraordinarily large, it had not been enough, in his opinion. He needed another season and more troops. He also needed ten more sail of the line, so that, among other things, he would have enough seamen to conduct amphibious operations. He was having great difficulty with the number he had. The promised help from Loyalists never materialized.