SCAPA FLOW

The Orkney Islands lie off the north of the British mainland, separated from the rest of Scotland by the dangerous tide-ripped waters of the Pentland Firth. The largest of this archipelago of islands is simply called the Mainland, where the main town of Kirkwall is situated, a place of charming streets dominated by a beautiful Viking-age cathedral. The Mainland lies in the middle of the archipelago, dividing the North Isles on one side and the South Isles on the other. The South Isles form a sort of natural circle, enclosing a large natural anchorage about 10 miles across and 8 wide. This virtually land-locked body of water is known as Scapa Flow. With only two navigable entrances to the west and south, it forms a large and readily defensible anchorage. Elsewhere, the low brown-and-green islands enclose it, like a protective mantle.

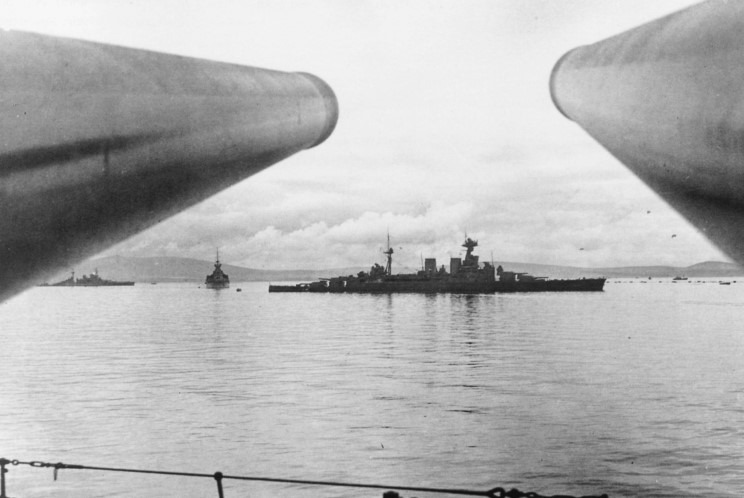

Shortly before World War I, Scapa Flow was chosen by Admiral ‘Jackie’ Fisher as the wartime base for the British Grand Fleet. It was ideally placed to coordinate the distant blockade of the German coast, and as a base from which the fleet could sortie if its German counterpart put to sea. It was from Scapa that Admiral Jellicoe’s dreadnoughts steamed off to fight the Battle of Jutland, and it was there in 1919 that the vanquished German High Seas Fleet was brought, and interned. While peace ended this major naval presence, a small naval base was retained there during the inter-war years. Then, in 1939, as the clouds of war were gathering, the British Admiralty ordered the Home Fleet to Scapa, as the naval strategy employed in the last war was considered just as effective in a new one. So, once again, Scapa Flow became a major wartime anchorage, and a home to hundreds of ships and tens of thousands of men.

Some of them loved the place – the tranquillity, the natural beauty and the mellow landscape are easy to fall in love with. Others found Scapa a living hell. To them, it was the end of the earth, a bleak and cold spot where the wind always blew, and winters were often cold, wet and stormy. Jellicoe’s successor, Admiral Beatty, called Scapa ‘the most damnable place on earth’, vastly preferring the gaiety of a big city and a lively social scene. Most of the sailors who served on ships based in Scapa during the two world wars probably agreed with him. The shore facilities there were limited – the navy supplied a theatre, a cinema, a few bars or canteens and sports fields, but it was nothing compared to Portsmouth, Plymouth or Chatham. There were few women, and most of them were wearing uniforms. There was little else to do but stay cooped up on your ship and wait for something to happen. In May 1941, that wish was granted.

When the war began, this battle fleet swinging at anchor in Scapa Flow had been christened the Home Fleet in 1932, and was the direct successor of the Grand Fleet of World War I. The defences of Scapa Flow were woefully inadequate – a point driven home early on 14 October 1939 when the U-boat U-47 penetrated its makeshift defences and sank the old battleship Royal Oak – an attack that claimed the lives of 834 of her crew, many of whom were boy seamen. The fleet decamped to the West Coast of Scotland until March 1940, by which time Scapa’s defences had been put in order. At first, this meant protecting the navigable entrances using torpedo nets and underwater listening equipment, and the smaller ones with new blockships. Next came coastal batteries, radar stations, flak defences, airfields and fighter aircraft. By early March, Churchill could tell the War Cabinet that Scapa was ‘80% secure’.

With its base thus reasonably secure, the Home Fleet was free to set about maintaining its distant blockade of Germany, by obstructing German egress from the North Sea. Then, in April 1940, the whole situation changed. The German conquest of Norway rendered the blockading line between Shetland and the Norwegian coast untenable. Instead, the Home Fleet had to maintain its patrol line between Greenland, Iceland, the Faeroe Islands and Shetland. In the Cold War, this would be known as the GIUK gap – the route by which Soviet submarines could reach the Atlantic. In 1940, it was merely the redeployment of the distant blockade. This time, though, the rough seas and harsh conditions meant that cruisers formed the mainstay of the patrol line, rather than smaller warships.

The German occupation of Norway also placed Scapa within easy range of German bombers. Intermittent air attacks first started in October 1939, but by April 1940 the ‘Orkney barrage’ was in place, a wall of flak designed to protect the anchorage, using land-based anti-aircraft batteries and the air defence firepower of the Home Fleet. It was first to be put to the test on 2 April, when it proved a resounding success. By June, all of Scapa’s defences were complete. As a result, the anchorage remained immune from German attacks of any kind for the rest of the war. This went some way to neutralising the advantage handed to the Germans by their conquest of Norway. So, from that summer, and for the rest of the war, British reconnaissance aircraft and submarines routinely patrolled the Norwegian coast, looking for German warships.

In theory, the proximity to German-occupied Norway could have been a major problem. However, by the summer of 1940 the ‘Orkney Barrage’ had been tried and tested. The wall of flak thrown up during the barrage meant that no German aircraft could penetrate it. With no land to the east, radar stations could pick up approaching German bombers as they crossed the North Sea, and the fleet and its shore-based defenders would be ready for them. In addition, there were four airfields on Orkney – two run by the Fleet Air Arm and two by the Royal Air Force. They were all well provided with fighters, and these, together with nearby airfields in Caithness, meant that any large-scale Luftwaffe attack would be repulsed with potentially heavy losses. In fact, once the effectiveness of all this was demonstrated, German air attacks ceased completely. Instead, fighter-bombers based in Orkney and Caithness conducted regular sorties against German coastal shipping in Norwegian waters.

The other advantage of this secure anchorage was its location. While the homesick crews might complain about being stationed far from the fleshpots of London, or even Portsmouth or Plymouth, in strategic terms Scapa Flow was the perfect place for the Home Fleet. Orkney was far from the Luftwaffe airfields in France and the Low Countries, whereas the naval bases on Britain’s south coast were just a few minutes’ flying time away. To reach Scapa Flow, any German sortie from the Skagerrak would have to traverse the North Sea and reach the Atlantic by way of the Norwegian Sea and the Greenland–Iceland–Faeroes–Shetland gap. Scapa Flow was much closer to the Skagerrak than these southern bases, and virtually on the doorstep of these northern sea entrances into the Atlantic. In terms of ‘sea control’ it was perfect – the fleet there acted as the stopper to a bottle. Any German sortie would have to run the gauntlet of the fleet before it could threaten the Allied convoy routes. So, regardless of the grumbling of the seamen, Scapa Flow remained the wartime base of the fleet.

THE DISTANT BLOCKADE

When in Scapa Flow, the fleet flagship swung at its mooring just off the island of Flotta, where an underwater cable ran out from the island to the mooring buoy.6 This carried a secure telephone line, which ended in a green telephone sitting on the desk of the fleet’s commander-in-chief and provided a direct line that ran straight to the Admiralty in Whitehall, allowing the admiral to talk to both the War Cabinet and Prime Minister Winston Churchill. This meant that any intelligence reports reaching the Admiralty could be conveyed to the Home Fleet within a few minutes. If the flagship were at sea, then both the admiral and the fleet commander had to use the much less secure medium of encoded radio signals, which were, of course, vulnerable to interception by the enemy. In the events that unfolded in May 1940, these lines of communication played a vital part in the drama.

The stated aim of the Home Fleet was the defence of British home waters, and the vital maritime supply routes leading to British ports. However, as the war played out, various areas were devolved into separate commands. The coastal waters of the English Channel and the English east coast were administered separately, as the lighter forces stationed there fought their own private war, protecting coastal convoys and harassing enemy ones. The Western Approaches to the British Isles – those sea lanes to British ports – were controlled from Plymouth, and later from Liverpool. That, then, left the Home Fleet free to concentrate on its main job: the containment of the German Kriegsmarine within the North Sea, and the destruction of enemy warships attempting to break out into the Atlantic.

During the Napoleonic Wars, Britain maintained a close blockade of French-held ports on the European mainland, whereby any French sortie from Brest, Toulon or the Baltic would be met by a British fleet. Clearly, however, this strategy was less effective in an age of submarines, radio transmissions and long-range guns. So, the notion of a distant blockade was devised, involving a blockade being established further from enemy-held ports, but within range of friendly naval bases. The result was the same. In World War I, the naval blockade of Germany was the single most effective tool in the Allied arsenal. Imperial Germany relied heavily on maritime imports for its raw materials and foodstuffs. In November 1914 the British declared the North Sea a ‘War Zone’, and ships suspected of heading to enemy ports or even of carrying cargo bound for Germany were seized. Even neutral ships were stopped and inspected, despite a slew of complaints.

Blocking off the English Channel was easy enough – a job given to the Dover Patrol. Sealing off the top of the North Sea was a little more difficult. The Northern Patrol operated between the Norwegian coast and Orkney, and proved highly effective at stopping virtually all foodstuffs and war materials reaching Germany. By 1916, this had resulted in growing food shortages in Germany, and by the end of the war the German people faced starvation, a major factor in the cessation of the conflict. In 1939, the situation was very similar, and the same blockade tactics were employed. Hundreds of small patrol craft, such as requisitioned trawlers, were pressed into service, but this time, rather than a full naval blockade, this was called ‘British Contraband Control’. Once again, Orkney became the base for the northern part of this blockade, and within weeks hundreds of tons of war materials were confiscated from German-registered or neutral ships.

Nazi Germany responded by imposing its own economic blockade, using mines to disrupt British coastal convoys, and U-boats to harry convoys in the Western Approaches. Soon, both sides were feeling the effects of shortages. Then, in the spring of 1940, the capture of Norway and the Fall of France changed everything. Now, the Northern Patrol had no firm anchor on the Norwegian coast. Now, German U-boats could use French Atlantic ports, and reach their patrol areas in half the time. So, a new strategy was needed. This involved the stepping up of convoy efforts, helped by the increasing unofficial support of the USA. It also meant abandoning the existing patrol line and moving it back, out of easy reach of Norwegian airfields.

This required the re-establishment of a patrol line running between Denmark and Iceland, Iceland and the Faeroes, and the Faeroe Islands and Shetland, Orkney and the Scottish mainland. Of these, the Pentland Firth south of Orkney and the gap between Orkney and Shetland were easily covered by small patrol craft, destroyers and aerial patrols. The three more distant gaps were more of a problem, one that was addressed with the use of all-weather small ships such as ocean-going trawlers, corvettes and destroyers, supported by heavy and light cruisers. The distant blockade was just as effective – although the distances involved were greater and more ships were needed to do the job.

This business was actually made a little easier in April 1940 when the Germans invaded Denmark. At the time, Iceland was a sovereign nation but was united to Denmark under the rule of the Danish crown. In consequence, Iceland was considered neutral. However, following the German invasion of Denmark the British sent troops to occupy Iceland, after the Icelanders refused to join the Western Allies. So, from May 1940, Iceland was controlled by Britain, until July 1941, when it was transferred to American control. Although officially Iceland remained neutral throughout the war, its government actively cooperated with the Allies, and in 1944 it declared its independence from Denmark. As a result of this, the Allies gained vital air and naval bases on the island, which rendered the distant blockade of Germany far more effective. Now, British warships could put in there to refuel or shelter from storms, and search aircraft could range far out into the Arctic Sea.

While smaller craft maintained the distant blockade from Greenland to Orkney, larger warships – mainly cruisers – also patrolled the same waters, ready to intercept any German warships attempting to break out into the North Atlantic. While a cruiser armed with 6in. or 8in. guns lacked the firepower to stop a Scharnhorst, Gneisenau or Bismarck, they could use their radar to shadow them and thereby help larger British ships intercept the enemy. That was where naval intelligence came in. The Admiralty relied on a whole range of sources – from signal intercepts, Enigma decryptions, spies, resistance cells, patrolling submarines and search aircraft – to let them know when a German breakout was imminent, whereupon the commander-in-chief of the Home Fleet would send a powerful force to intercept the enemy.

This of course demanded the timely acquisition of suitable intelligence, and a certain amount of forewarning. It took roughly 30 hours for a battleship to cover the 800 miles from Scapa Flow to the Denmark Strait between Greenland and Iceland. It took half that to reach the Iceland–Faeroes gap. So, not only did the fleet need advance warning, but its commander also had to predict which of these routes the German warships would take. That meant that the green telephone was crucially important, as were the search and photo reconnaissance planes that might spot the enemy on their way towards the Atlantic. Meanwhile, the Home Fleet’s capital ships – the battleships, battlecruisers and aircraft carriers – swung at anchor in Scapa Flow, or conducted training exercises, while their crews waited for that all-important signal that would galvanise them into action.