Iphicrates was born towards the end of the fifth century into a poor and rather obscure Athenian family. Despite his lowly background he rose to a position of command in Athens, fighting in a number of campaigns including the Corinthian War and the Social War, he also spent time in Persian service after the Peace of Antalcidas. Diodorus places his peltast reforms after 374, following his Persian sojourn, using his experiences prior to that date to develop this new type of soldier.93 The exact dating of the reforms is not relevant here, but their nature certainly is, as it was this type of soldier that constituted the bulk of Alexander’s mercenary forces. I have also tried to argue earlier that Alexander’s heavy infantry were essentially a version of Iphicratean peltasts, being equipped as they were with a small shield and very little body armour.

The primary sources of information that we have for the peltast reforms of Iphicrates are Diodorus and Nepos, both of whose accounts are very similar. According to them the most significant changes were as follows:

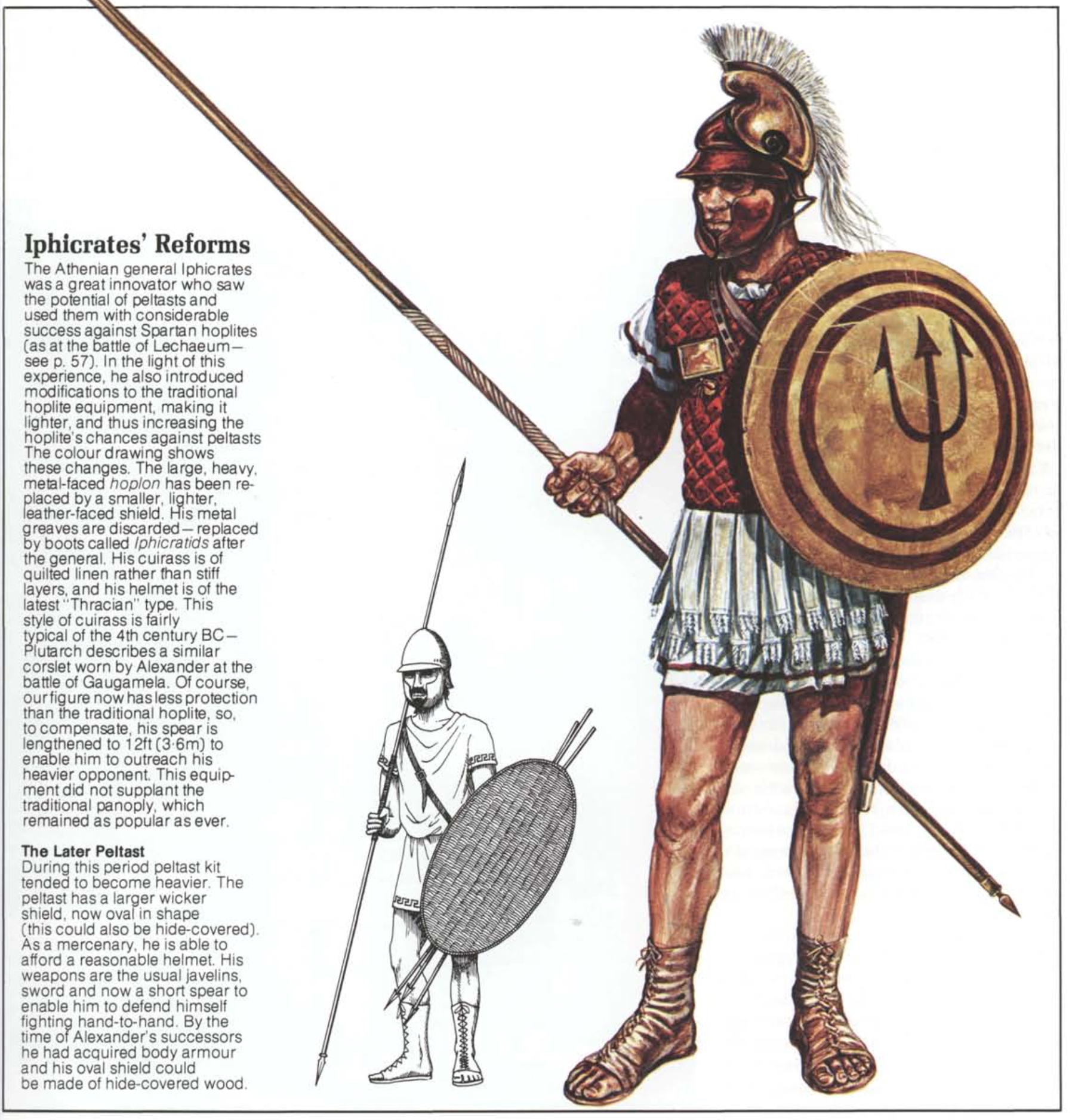

Iphicrates replaced the large (shield) of the Greeks by the light pelte, which had the advantage that it protected the body while allowing the wearer more freedom of movement; the soldiers who had formerly carried the [large hoplite shield] and who were called hoplites, were henceforth called peltasts after the name of their new shields; their new spears were half as long again or even twice as long as the old ones, the new swords were also double in length, In addition Iphicrates introduced light and easily untied footwear, and the bronze harness was replaced by a linen covering, which although it was lighter, still protected the body.

Diodorus regards these changes as having been introduced into the existing hoplite troops and in the process discounts the possibility of already existing peltast-style light infantry. Diodorus’ failure to realize the existence of peltast troops before Iphicrates is indeed very striking. In this omission Diodorus shows his serious lack of understanding of the military situation of the day. Modern commentators have frequently been struck with the absurdity of this, and have taken up an opposite attitude. For them the change was a trivial one and consisted chiefly in the standardizing of the existing, but rather haphazard, peltast equipment. This argument, however, simply will not do. It assumes that the light-armed skirmishers of earlier narratives were equipped in the same manner that Diodorus describes. This simply cannot be the case; light-armed skirmishers would not have carried a sword and spear twice the length of those carried by hoplites. Earlier narratives also tell of peltasts actually throwing their spears. If Iphicrates was standardizing that which already existed then why did he not provide his troops with these throwing spears? We are surely not to believe that they carried these as well. Some other explanation must be sought.

Was Iphicrates actually inventing a new type of peltast, one with specific and specialized equipment? The other extreme view is that Iphicratean peltasts were in no way different from Thracian peltasts. On this interpretation, Iphicrates’ reforms were of little significance, as troops of exactly the same type existed already in Thrace. The truth probably lies somewhere between these two extreme positions. There was probably no uniformity of peltast equipment before Iphicrates, some using primarily throwing spears, some longer spears, still others using swords of various sizes. The size of the shield probably varied too. I suspect therefore that Iphicrates studied the light infantry of his day and based his reforms around choosing from the various groups the equipment that best suited the type of soldier that he was trying to create. We may see Iphicrates therefore not as creating something entirely new, or as standardizing that which already existed, but as refining the equipment and tactics of the peltasts of his day.

Mercenaries had not been a significant part of the military forces of the city-states in the fifth century. There was, on the one hand, very little fiscal means to support such troops, and, on the other, a generally held belief that it was a citizen’s duty to take up arms and defend his polis as need arose. Any Greek mercenaries that did exist were generally employed in Persia or Egypt. Mercenaries were also employed in Sicily in significant numbers from an early date. By 481 it seems possible that Gelon, tyrant of Syracuse, maintained an army that included as many as 15,000 mercenaries. They presumably constituted a significant part of the army that won the decisive victory over the Carthaginians at Himera. The most significant event that sparked a major increase in the employment of mercenary troops on mainland Greece was the Peloponnesian War. The Peloponnesian states were the first to employ mercenaries in great numbers. These mercenaries were initially not light-armed troops but hoplites from Arcadia. Athens was slow to hire such troops, largely because of the geographical difficulty in reaching them, but by the end of the war mercenaries of all kinds were finding employment on both sides. The reasons for this change lay in the nature of the war itself. The war was prolonged and almost continuous and there were few large-scale set piece battles fought; most engagements were on a small scale and fought by troops who were relatively lightly equipped and very mobile. Mercenaries were simply better at this kind of combat than heavily armoured hoplites. The hiring of mercenaries was made possible now, and less so earlier, by the relative prosperity of the warring states as compared to earlier in the fifth century.

The end of the Peloponnesian War did not see an ending of the employment of mercenaries in Greece. The peace itself led to a large number of men who had become accustomed to earning their living as hired soldiers suddenly becoming unemployed. This would generally have a destabilizing effect upon any society, but they would not have stayed unemployed for long. The political situation in Greece in the fourth century meant that there were always potential paymasters. Their other great sphere of employment, Persia, was also undergoing change. The central authority of the Persian Empire had begun to weaken. The local governors and satraps grew more independent and ambitious. Their position needed military support, and they found it most readily in Greek mercenaries. It had long been recognized that mercenaries formed a more secure power base for tyrants, rather than citizen soldiers whose loyalty was more open to question if a usurper came along. Greek mercenary infantry in Persian service continually proved themselves more capable than anything that the native Persians were able to achieve, so the great king himself was also forced to hire his own contingents to keep pace with his potentially disloyal satraps. We see this to be true during the reign of Alexander too: the only quality infantry that Darius had at his disposal were the Greek mercenaries. Initially 20,000 strong at the Granicus, they had been reduced to perhaps only 2,000 by the time of Gaugamela. This was because of successive losses at the Granicus and Issus, but probably due to desertion too as it became apparent that Alexander was a more attractive paymaster. The League of Corinth had specifically outlawed a Greek taking up arms against another Greek; this decree had meant little at the outset of the campaign when Persia looked like a good bet for victory. At the time of the battle of Gaugamela in 331, however, Darius found it almost impossible to hire more Greek hoplite mercenaries. This was partly because he was no longer an attractive employer, partly because of the distance from Greece, and partly because Alexander was hiring them in increasing numbers, thus reducing the available pool.

#

The Spartan King Agesilaus died at the age of 84 on the way home from Egypt. There seems to have been something unhappily circular in the defence economy over which he presided: mercenary expeditions raised money by which the Spartan state was enabled to hire more mercenaries. However, it may be pleaded that Agesilaus was in fact trading military expertise for manpower.

Agesilaus’ death marks the end of an epoch in Greek history. His skilful operations had to some extent concealed the serious decline in the fighting potential of the Spartan citizen army. The development of new forms of warfare had been in itself an admission that the supremacy of the Spartan hoplite phalanx was at ‘an end. Since the Peloponnesian War, the Spartan army had been substantially remodelled; this in itself reflected a decline in numbers of the fully-enfranchised citizens who formed the backbone of the heavy infantry. The decline could in some degree be paralleled by population decline in other Greek states, but apart from all general tendencies Spartan military strength had also been seriously affected by the losses suffered in a devastating earthquake which occurred as far back as 465 BC – before the Peloponnesian War had even begun.

The Spartan army in the fourth century consisted of six battalions (morai). Each of these was under the command of a polemarch and, according to contemporary historians, consisted of 400 or perhaps 600 men. Both citizens and non-citizens served in it. Within the mora, there was subdivision into smaller units, as previously with the lochos. During the Corinthian War, a Spartan mora, after escorting a contingent of allied troops back to the Peloponnese, was intercepted in the Isthmus and routed with crippling losses by the Athenian commander Iphicrates. In numerical terms, casualties of 250 out of a total strength of 600 men, which on this occasion the unit contained, were extremely serious. The strategy and tactics of Iphicrates were even more significant; his victory was gained against hoplites by the use of lightarmed troops. The Spartan debacle, which occurred outside Corinth, can be paralleled by others in Greek military history, where (as at Amphipolis in the Peloponnesian War) incautious troops marching close under enemy walls exposed themselves to a sally from the city gates.

The action, however, was still more reminiscent of Sphacteria. The Spartans were overwhelmed by missiles and never allowed to come to grips. At Sphacteria, Spartan lack of foresight, combined with some bad luck, had produced the fatal situation, but Iphicrates was the deliberate architect of his own victory, which vindicated to the full his new strategic and tactical concepts of light-armed warfare. Indeed, there is a third reason for regarding Iphicrates’ success on this occasion as historically significant: the troops he commanded were mercenaries and their victory was gained against a predominantly citizen force.