Butler’s Rangers. They were Loyalist forces recruited in 1777, during the Revolutionary War, by the fugitive Mohawk Valley Tory, Major John Butler. The men were mostly Loyalist elements from around Niagara, New York. The Rangers were both feared and despised along the New York and Pennsylvania frontiers, fighting with the British alongside Joseph Brant in the Wyoming and Cherry Valley Massacres, in 1798.

John Butler had only about three hundred Rangers to oppose the mighty Sullivan-Clinton force because his Indian allies, preferring retreat to annihilation, offered little resistance to any of the three armies. Brant and Walter Butler set up an ambush to slow down Sullivan. But, outmaneuvered, the ambushers fled northward to Niagara as the troops swept through the Iroquois country, burning villages and crops, sometimes avenging past atrocities with a few of their own. Some soldiers scalped Indians they had killed. An officer told of finding two dead Indians whose bodies he then had skinned “from their hips down for boot legs … one pair for the Major the other for my-self.” Civilian Rebels joined the troops one day, locked an old Indian woman and a boy in a cabin, and set it afire.

After one of the few armed encounters, surviving Indians went off with two captured Continentals. Comrades later found their bodies: “The Indians … tied them up & whipped them prodigiously, pulled out their finger and toe nails, cut out their tongues, stuck spears and darts through them & set the Leuts [lieutenant’s] head on a log with the mouth open: we could not find the other head.”

As part of the Sullivan expedition, a detachment marched from Fort Stanwix and crossed Oneida Lake to raze the principal settlement of the Onondaga, who had not taken either the Tory or Rebel side. Leaders of the Oneida, allies of the Patriots, begged the Continentals not to attack the Onondaga, stressing their neutrality. But expedition officers dismissed the claim. The Continentals reported slaying twelve Onondaga, destroying about fifty log houses, burning “a large quantity of Corn and Beans,” and killing “a number of fine horses & every other kind of Stock we found.” The attack turned the Onandaga into foes of the Patriots.

Sullivan went about as far north as Genesee, New York. His expedition produced devastation as methodical as Washington had ordered. In a report to Congress, Sullivan said that “every creek and River has been traced” and “not a single town left” in the Iroquois country. His men had wiped out at least forty villages and, by Sullivan’s “moderate computation,” had destroyed at least 160,000 bushels of corn. In one large village soldiers cut down fifteen hundred peach trees.

Indian families, fleeing before the soldiers and carrying few belongings, sought refuge at the British base at Niagara, more than one hundred miles beyond Genesee. Thousands became homeless people seeking help. By the time the first of them reached Niagara, the chill of autumn was in the air, a prelude to the most severe winter in memory. The Butlers and other Loyalists built huts around the fort for the more than five thousand Indians gathered there. Food was scarce, and hunters risked freezing to death when they sought game. Hunger, cold, and disease killed an unknown number of the Indian refugees—perhaps hundreds.

Originally Washington had hoped that the western force sent up the Allegheny River valley would link up with the Sullivan-Clinton expedition in a great sweep that would subdue the entire Iroquois Nation. But, fearing that he would be overextending his forces, Washington changed his mind and left the western commander to venture on his own. The Allegheny Valley expedition, which did not lose a man, reported extensive destruction, burning down thirty-five houses, including some large enough to shelter three or four families, and putting the torch to fifteen hundred acres of corn. The western Indians also fled toward Niagara. In their flight, they left behind packets of trade pelts and other valuables, which the invaders seized as booty.

The western campaign turned that frontier into a cauldron of competing foes. Virginia and Pennsylvania argued over where their boundary should be drawn. Settlers, thinking the frontier had been freed of the Indian menace, began heading westward. Among them were Tories escaping persecution and seeking the protection of territory around British-held Detroit. Patriots feared that Tories would seize lead mines, vital to Rebel ammunition production, on the western Virginia frontier. A Virginia militia force swooped down on a Loyalist settlement near the mines and reported, “Shot one, Hanged one, and whipt several.” The Virginia House of Delegates confiscated the Loyalists’ land and lauded the militiamen for “suppressing a late conspiracy and insurrection on the frontiers of this State.” Skirmishes between western Tories and Rebels would continue through the war.

The Sullivan-Clinton expedition inspired small hit-and-run vengeance raids that began soon after the new year. Then, in May 1780, Sir John Johnson mobilized a force of more than five hundred men, made up of Indians and companies of his own King’s Royal Regiment. Loyalist boatmen took the raiders down Lake Champlain to a landing below Crown Point, where they went ashore to begin an overland trek. One detachment went directly with Johnson to his birthplace, Johnstown, New York. At Johnson Hall his men dug up two barrels of family silver plate that he had buried before his flight to Canada in 1776. The treasure, carefully inventoried, went into Loyalist knapsacks for the return trip.

A second detachment struck settlements south of the town, burning 120 houses, barns, and mills. They killed or wounded several men who were considered special enemies or were simply defending their homes. Some Tories were also killed and scalped by mistake in a frenzy of looting and burning. At sunset, on a hill in one settlement, lost dogs from smoldering homes joined the dogs of missing masters, and the forsaken pack howled deep into the night.

Rebel militiamen and Continentals belatedly responded to the raid. Johnson eluded them, even though he was burdened by his silver plate and a couple of dozen prisoners. He had also rounded up 143 Loyalist men, women, and children who had been living fearfully in Rebel territory. Pursuers finally got on Johnson’s trail as his fiery nineteen-day invasion was ending. When Johnson, his men, and their guests boarded bateaux for their return voyage, the pursuers were right behind. But they had neither the boats nor provisions to continue their pursuit.

The Johnson raid raised Loyalist morale in the borderland, deprived the Continental Army of food, and aided recruitment. With their families safe at Niagara, many of the Tory men Johnson had rescued signed up for the King’s Royal Regiment, completing the muster of one battalion and starting a second.

Sir Frederick Haldimand, Guy Carleton’s successor as “Captain General and Governor in Chief in and over our Province of Quebec in America,” believed that, in the wake of Burgoyne’s stunning defeat, a new invasion of Canada was likely. He saw the Rebel settlements of the frontier as a potential staging area for a strike across the border.60 To diminish that threat—and stop the flow of grain to the Continental Army—he ordered attacks on the people and crops of the Schoharie and Mohawk valleys.

Haldimand, born in Switzerland in 1718, became an officer in the Prussian army at the age of twenty-two. On the eve of the French and Indian War, as a soldier of fortune, he joined the Royal Americans, who included deserters from, or veterans of, European armies, along with Swiss and German settlers of Pennsylvania. After distinguished service in the war, he remained in the army and in America, assuming commands in posts from Massachusetts to Florida. His varied postings and familiarity with American ways made him one of Britain’s most experienced North American officials.

Under his direction, Sir John Johnson assembled a main force of nearly one thousand men, including about 180 British Army Regulars, twenty-five Hessians; 150 Rangers, under Col. John Butler; about two hundred men of the King’s Royal Regiment; many Tories in independent companies; and about 580 Indians. Haldimand rounded up an additional 970 men for diversionary raids near Saratoga and down the Richelieu River route to the Hudson River.

Scouts went out to alert Tories along the routes, assuring them that they would be escorted to Canada and resettled in safety if they believed they had endangered themselves by aiding the invaders. A scout from the King’s Royal Regiment, sent specifically to seek out Loyalists who might join the invasion, was caught, tried as a spy, andhanged, as was a Continental Army deserter who was caught recruiting Tories.

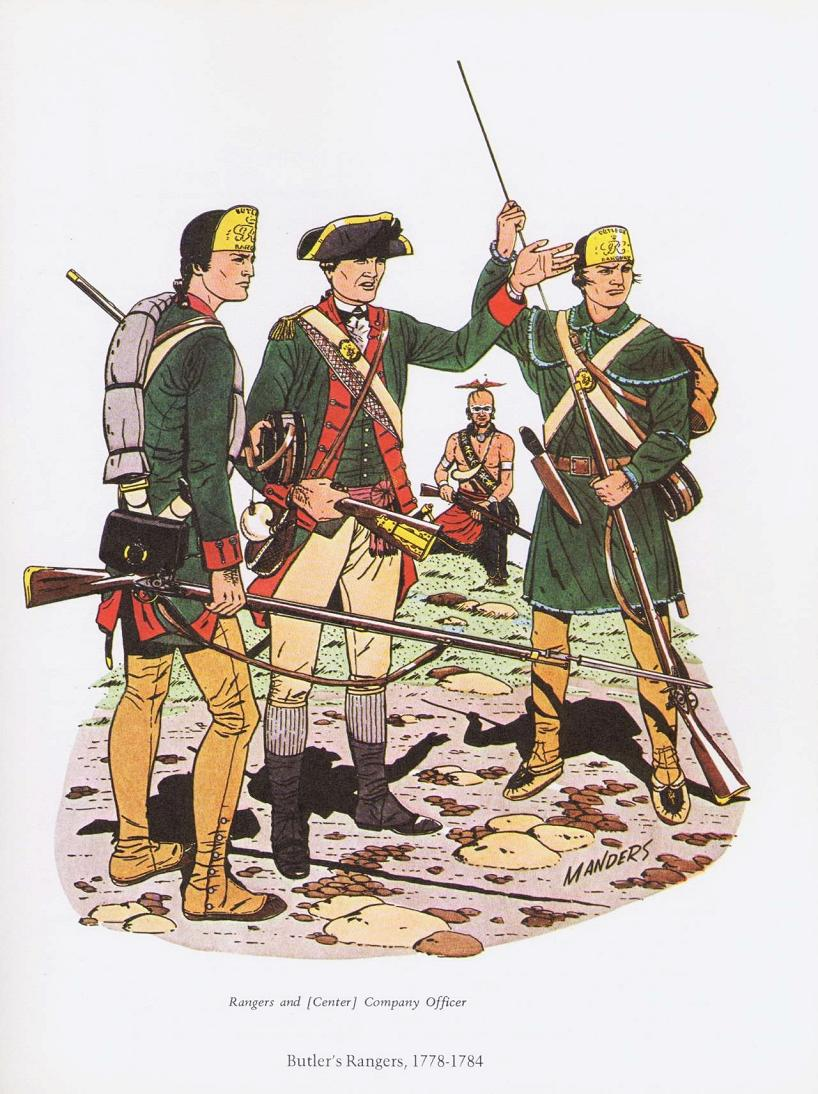

Men took down their muskets and went off to join the side of their choice, leaving wives and children behind. A Mohawk Valley man wrote about his father, who left his farm to join Butler’s Rangers: “It was a momentous struggle, a frightful warfare… . The farms were left to the care of the women, who seldom ate the bread of Idleness… . They spun, they wove, they knit, prepared their own flax, made their own homespun gowns, the children’s dresses, they churned, made cheese, and performed all the various duties of domestic and social life … my father’s mind was at ease about the affairs of the Farm.”

Three forts defended the verdant Schoharie Valley, Johnson’s first objective. The Lower Fort, as it was called, had as its core a stone Dutch Reformed church. Surrounding it was a stockade encompassing about an acre of land dotted with small huts. The fort’s powder was stored beneath the pulpit, and in the belfry was a platform for lookouts and rifle marksmen. Outside one of the two corner blockhouses was a tavern. The Upper Fort was about fifteen miles south, near the village of Schoharie; the Middle Fort was just below Mid-dleburg.

On October 16 Johnson’s expedition camped near the Upper Fort, which was built around a farmhouse and barn, its stockade surrounding about two and a half acres. The next morning a soldier outside the fort spotted the Loyalist force and ran to give warning. A signal gun boomed. Hearing it, Johnson ordered the destruction to commence. Flames and smoke began rising from barns and deserted houses. Cattle and pigs lay dying, their cries and their blood drawing dogs and vultures.

The invaders broke into houses, took what they wanted, and torched them. Some people stayed to defend their homes, which in this prosperous farmland were framed and painted wooden buildings, not log cabins. The raiders moved on quickly, heading for the Middle Fort through a day that was growing gray under wind-whipped sleet and snow. Johnson set up two small cannons that began firing at the fort as his Rangers and Indians cautiously approached it. After a whilethe firing stopped, and men in the fort saw a white flag appear in the enemy ranks. The flag bearer began walking forward, flanked by an officer in the green coat of Butler’s Rangers and a fifer playing “Yankee Doodle,” still a mocking tune to the ears of a Rebel.

The commander of the Middle Fort, a Continental in charge of militiamen accustomed to having their own officers, ordered the gates opened to the flag of truce. Timothy Murphy, a militiaman, defied the order. He was a sharpshooter, one of Morgan’s riflemen in the Battle of Saratoga. Now he shot at the flag party—to warn them off, not to hit them. He told his stunned commander that he believed that the white flag was a ruse to allow the officer to assess the fort’s garrison. If the Ranger did enter, he would see how few defenders there were. The flag party turned back, then came forward two more times, and each time Murphy fired a warning shot. Murphy’s defiance undermined the authority of the Continental officer, who threatened a court-martial but finally turned over command of the fort to a militia colonel.

Johnson decided to march on, bypassing the fort to continue destroying every Rebel farm in his path—while sparing Tory property. After another bivouac in the Schoharie Valley, he headed for the Mohawk Valley, pursued by frustrated and outnumbered Rebel militiamen only able to “hange on their Rear.” As soon as Johnson left, outraged Rebels burned the untouched Tory farms, completing the absolute destruction of the valley’s crops and livestock. Tories fled northward, joining Johnson’s followers.

At the Mohawk River the raiders split into two detachments to loot and raze along both sides of the river, camping for the night near the town of Root. On the morning of October 19 the main force crossed the Mohawk and headed for the German village of Stone Arabia, the center of an area settled by immigrants from a part of Germany known as the Palatinate. At nearby Fort Paris, Col. John Brown mustered about three hundred men, including a few Oneida Indians, and, astride his small black horse, led them toward Johnson’s force. Brown was killed in an ambush. His men fled, leaving behind the fallen to be scalped.

Johnson’s “Destructionists,” as raiders were sometimes called, kept on swooping down on farms. Among his men were settlers who had lived in these houses, built these barns, tilled these fields. But now they were Tories on a mission, and to them, somehow, this rich valley had become an alien land. A farmer, hidden in the woods with his family, watched his own farm vanish in flames. He saw the Indian Tories move on, swinging firebrands over their head until they blazed, then touching them to barns full of grain. After the Indians left, the farmer found seven hogs dead in their pen, killed by a pitchfork taken from what had been a barn. And so it went, farm after farm.

British soldiers in the attack force sometimes guarded prisoners to protect them from the Indians, whose behavior was unpredictable. At one farm Indians took a woman and her seven children out of their house, then loaded them and armfuls of loot into a horse-drawn wagon. Around that time Johnson was told that Continentals and militiamen were on their way from Albany and Schenectady. He released the woman and her children, except for her fourteen-year-old son, presumably kidnapped to become a future Ranger.

About nine hundred Rebels, most of them militiamen, caught up with the raiders toward the end of day. In a twilight skirmish Johnson tried to set up a battle line but failed to hold off a Rebel charge. Men of Johnson’s own regiment were driven back—” running promiscuously through and over one another” in the dark, a Tory said. As the Johnson Destructionists settled for the night near the battlefield, the Rebels’ commander inexplicably ordered his men to camp about three miles away. He planned to strike the next morning. By then Johnson and his force were well on the way toward Canada.

The diversionary raids were as successful as the main raid. Maj. Christopher Carleton, a nephew of Sir Guy Carleton, headed a force of nearly one thousand Regulars, Indians, and Tories down the Champlain Valley into the upper Hudson River valley. Carleton was knowledgeable about Indian culture, had had himself tattooed, and attimes wore a ring through his nose. He had taken an Indian mistress before marrying the sister of his uncle’s wife. He knew the frontier wilderness trails as well as an Indian. He was an inspiring leader in a stealthy campaign that called for night marches and fireless camps.

Early in the three-week expedition, near the southern shore of Lake George, a King’s Ranger spotted about fifty Rebel soldiers leaving Fort George. A mixed force of Rangers, Indians, and Regulars surrounded the men and swiftly killed twenty-seven. Eight men were captured. The rest escaped into the woods. The fort surrendered. After looting and burning it, the raiders marched on, their prisoners carrying the Indians’ plunder. By the loose rules of raiding, Indians, male and female, were given looting rights, some becoming quite discerning. One settler told of an Indian who stole plates from a dark house. Once outside, he discovered they were pewter, not silver, and disdainfully threw them away.

A party of militiamen was sent to the area later to bury the dead. “We found twenty-two slaughtered and mangled men,” one of them remembered. “All had their skulls knocked in, their throats cut and their scalps taken. Their clothes were mostly stripped off… . The fighting had been mostly with clubbed muskets, and the fragments of these, split and shivered, were laying around with the bodies.”

A diversionary raid aimed at Schenectady, led by a former merchant in that town, shifted to the village of Ballston after militiamen mobilized on the route ahead. In Ballston, Indians broke into cabins and killed two men. Tory officers intervened, feeling that the Indians were turning too violent. In one cabin, an officer grabbed an Indian’s upraised arm, protecting an unarmed man defending his family. After the usual burning and looting, the Indians, Rangers, and Tory followers headed back to Canada with a string of prisoners.

Carleton’s men burned down a second Rebel fort and captured 148 Rebel soldiers, a large loss in a frontier of sparse garrisons. The raiders destroyed thirty-eight houses, thirty-three barns, six saw mills, and a grist mill. They estimated that they had torched fifteen hundred tons of hay. A detachment of Indians burned down thirty-two houses and their barns.81 Such inventories of desolation continued, year after year, raid after raid. At least twenty-nine raids struck towns in the Mohawk and Schoharie valleys in 1781 alone.

Col. Marinus Willett, a Continental Army hero, writing to Washington from Fort Herkimer in the German Flats in July 1781, estimated that one-third of the people on the New York frontier had been killed or carried off, one-third had fled the frontier but remained Patriots, and “one third deserted to the enemy.” Postwar records show that about 380 women became widows and some two thousand children lost their fathers. About seven hundred buildings had been burned and 150,000 bushels of wheat destroyed. Some twelve thousand farms had been abandoned. There is no reliable estimate of how many prisoners were taken. Some were exchanged; some did not return until a year or more after the war. Many died. Others, lured by offers of free land, became Tories and remained in Canada.

“I am really at a loss to know how to feed the troops,” the senior Continental Army colonel in New York wrote to Governor George Clinton, General Clinton’s brother, in September 1780. Two months later, reacting to the continuing loss of grain and flour from “the country which has been laid waste,” Washington told Governor Clinton that “we shall be obliged to bring flour from the southward.”

To the west, in the wild Ohio Country, under orders from Lord Germain in London, bands of Tories and Indians raided settlements on the Pennsylvania and Virginia frontiers and in the area that would become Kentucky. Germain, saying “it is The Kings command,” had instructed an obscure colonial official to “assemble as many of the Indians of his district as he conveniently can, and placing proper Persons at their Head, to … restrain them from committing violence on the well affected and inoffensive Inhabitants, employ them in making a Diversion and exciting an alarm upon the frontiers of Virginia and Pennsylvania.”

The official was Henry Hamilton, an Ireland-born veteran of the French and Indian War, who in 1775 had been made lieutenant governor and superintendent of Indian affairs at Fort Detroit (site of today’s Detroit). Hamilton was one of five lieutenant governors appointed to manage the Province of Quebec, whose boundaries had been extended by the Quebec Act of 1774 to include an immense expanse of land between the Ohio and Mississippi rivers.

Germain also authorized Hamilton to raise Tory regiments and offer each recruit the postwar promise of two hundred acres of land. With his Tories and Indians, Germain wrote, Hamilton might be able “to extend his operations so as to divide the attention of the Rebels, and oblige them to collect a considerable Force to oppose him.” Following Germain’s orders, Hamilton sent Tory-Indian raiders into a territory that Britain had prohibited its colonists from settling. But, defying the Crown, colonists had settled there. Their disobedience had marked them as Rebels, though there were enough Tories among them for Hamilton to find recruits.

White men had been paying bounties for enemies’ scalps since the French and Indian War. But Rebels on the frontier singled Hamilton out as the “Hair Buyer,” a label that found its way into numerous narratives. Hamilton himself routinely mentioned scalps in his reports. Early in 1778, for example, he wrote to Governor Carleton, saying that his Indians had “brought in seventy-three prisoners alive, twenty of which they presented to me, and one hundred and twenty-nine scalps.” Later that year Hamilton told Carleton’s successor, Frederick Haldimand, that “since last May the Indians in this district have taken thirty-four prisoners, seventeen of which they delivered up, and eighty-one scalps, several prisoners taken and adopted [by Indians] not reckoned in this number.” Neither letter mentions bounties for the scalps.

One of Hamilton’s operatives was Simon Girty, who had been captured by French-commanded Indians as a child in 1756 and raised by Senecas. He was freed after eight years and married a young woman who had been a captive of the Delaware tribe. Girty became an officer in a Pennsylvania militia and an Indian interpreter at Fort Pitt. When the Revolution began, by one story, Girty was confined to the fort as a suspected Tory; by another, he defected because he was disgusted with American treatment of Indians. Whatever the reason, he endedup in Detroit and became not only a captain and interpreter in the British Indian Department but also the most notorious Tory on the western frontier. Like Hamilton, Girty would get a label: “White Savage.” His infamy was based on his witnessing but not trying to stop the heinous torture of a Patriot—” they scalped him alive and then laid hot ashes upon his head, after which they roasted him by a slow fire.”

Virginia governor Patrick Henry feared that Hamilton’s raids would drive settlers out of the territory and give the British control over the western frontier. One of the frontier leaders was Lt. Col. George Rogers Clark, a lanky, red-haired militia officer from the first region west of the Allegheny Mountains settled by American pioneers (later Kentucky). In 1778, with Henry’s support, Clark and his force of frontiersmen headed over the mountains to capture the bases from which the raiders struck. He also wanted to establish American claims to a territory nearly as large as the thirteen colonies.

Clark easily took three British outposts. But the most important—Fort Sackville in what would become Vincennes, Indiana—was retaken by Hamilton and a mixed force of Indians, Tory militia, and Regulars.95 Hamilton decided to wait until spring to attack Clark and roll back the frontier to east of the mountains. Clark surprised him by leading about 175 men to the fort, through seventeen winter days of snow and icy streams. At Vincennes his men captured five Indians carrying American scalps. To terrify Hamilton’s men Clark bound the captives and tomahawked them in full view of the garrison. Hamilton surrendered the fort and was taken to Williamsburg, where Governor Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry’s successor, called him a “butcher of men, women and children,” put him in irons, and treated him as a criminal, not a prisoner of war. After eighteen months, through the intervention of Washington, he was finally freed in a prisoner exchange.

From New York to the Ohio country, the Indian-Tory raids on frontier settlements continued, becoming a war unto itself. To the west, in March 1782, Pennsylvania militiamen swooped down on the missionary village of Gnadenhutten. The Delaware Indians there, converted to Christianity, were suspected of being Loyalists. The militiamen rounded up the unarmed Indians and killed sixty-two adults and thirty-four children by smashing their skulls with mallets. Two boys escaped and spread word of the massacre. In an act of vengeance three months later, Delaware braves tortured a captive militia officer who had nothing to do with the raid and then burned him at the stake. After the Revolution ended, Fort Detroit in the west, like Fort Niagara in the east, remained a British garrison and a Tory haven. But George Rogers Clark’s thrust beyond the mountains did establish an American claim on territory that would become Kentucky and West Virginia. And in 1803 President Jefferson looked farther westward, asking Congress for approval of an expedition that would travel to the Pacific. As one of it leaders, Jefferson would pick William Clark, George Rogers Clark’s younger brother.

* In 1761 Crown Point was a British fort on the west side of Lake Champlain, evacuated by the French in 1759 after the British captured Ticonderoga.