The Clinton-Sullivan Expedition: Indians Fleeing Chemung

It’s the heat of summer in August 1779 in the village of Chemung in the Cayuga Nation of Iroquois. Something has spoiled the serene daily life you, a 12 year old boy named Bruce Longboat, used to live. Adults are stirring, speaking in worried voices. Warriors from other Iroquois nations arrive while clan leaders assemble. The life you have known is about to change for ever.

ALONG THE NORTHERN FRONTIER, MAY 1778-MARCH 1782

I have had a meeting with several of the principal Chiefs of the Seneca Nation… . There is just now a party of Senakies come in who have had an action with a number of Rebel forces on the Ohio, in which the Indians … took two prisoners & thirteen scalps.

—Letter from Col. John Butler to Sir Guy Carleton

The war against the homes and farms of Pennsylvania’s Wyoming Valley was rooted in an episode during Burgoyne’s Saratoga campaign. Sir John Johnson’s frontier comrade in arms, Col. John Butler, had led the band of Indians and Tories who ambushed Brig. Gen. Nicholas Herkimer and his men in the ravine at Oriska. Governor Carleton, impressed by Butler’s performance, authorized him to raise a corps of eight companies of Tory Rangers “to serve with the Indians, as occasion shall require.”

At least two of the companies, Carleton said, had to have men capable of “speaking the Indian language and acquainted with their customs of making war.” Butler and his recruiters would eventually enlist more than nine hundred men of all ranks. The corps, known as Butler’s Rangers, would fight frontier Rebels in New York and Pennsylvania, in the wild Virginia territory that would become Kentucky and West Virginia, and in the Old Northwest, which would become Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and part of Minnesota.

Many of the earliest recruits were descendants of German immigrants who lived in the Mohawk Valley. Others included Loyalists who called themselves Refugees. They had entered Canada from New York and Pennsylvania, leaving behind homes and farms that Rebels then confiscated. While recruiting these Refugees and Loyalist Indians, Butler created a network of spies and operatives stretching as far as New York City and Philadelphia. One of his agents guided escaped British prisoners to the safety of Canada. Butler also made use of information gleaned from deserters from the Continental Army and runaway slaves drawn to the Tories by the promise of freedom.3 Butler’s own Indians spotted Oneida and Delaware—Indians friendly to the Rebels—attempting to penetrate Butler’s network.

Ranger headquarters was at Fort Niagara, which the British had taken from the French in 1759. The fort stood on the western bank of the Niagara River (now Niagara-on-the-Lake, Canada). Rangers’ families settled there, keeping livestock and growing wheat, oats, corn, and potatoes.5 Strategically the fort gave Butler and his Mohawk ally, Capt. Joseph Brant, an entryway to the fertile river valleys of northern New York. Butler and Brant had met with Indian leaders and, in Butler’s words to Carleton, they “express the greatest desire to join me in an attack on the Frontiers of the Rebellious Colonies.” The Indians had dealt with British officials for generations, building a sense of trust.

A frontier raid did not always produce a written record. In obscure places people fought, people lived or died, and tales of atrocities spread and grew by word of mouth. Raids were not battles to be chronicled in the history of a Tory regiment. But the record of one early raid does survive. In May 1778, about three hundred white and Indian Tories, led by Brant, pounced on Cobleskill, thirty-five miles or so west of Schenectady. The hamlet consisted of about twenty families living along a three-mile stretch of a small river valley. Tories marked Cobleskill as a Rebel outpost with its own militia. Unlike many other isolated communities, the town was not fortified.

People of the embattled valleys usually lived around a fort. Typically it would have bastions jutting out at corners or along a side as strongpoints of defense. Major forts encompassed a large-enough area to accommodate nearby families. Emergency makeshift forts were also built around stone houses or churches. Beyond the fort were earthworks and perhaps a stockade enclosing tents or cabins. During times of sowing or harvesting, when farmers were most vulnerable, families made temporary homes within the stockade or in the fort itself. Farmers went out to their fields in the morning, armed with their muskets or escorted by militiamen, and returned to the fort at the end of day.

At the sound of alarm—such as three shots from a cannon—people fled to the fort. Able-bodied men mustered, prepared to sally out and defend the fort; older men became a fort guard. Some women cared for babies and young children. Other women and older children prepared places where they would care for the wounded, or they built fires for heating iron pots for melting down lead, which they poured into bullet molds.

When militia scouts reported seeing Indians near Cobleskill in May 1778, there was no local fort to run to. The captain of the militia sent men to ask for help at the nearest fort, about ten miles away. Officers there immediately sent thirty-three Continental Army men under Capt. William Patrick of Massachusetts. The Continentals joined fifteen militiamen who had assembled at a house chosen as headquarters. Scouts went out, encountered two Indians, and shot one dead.

Two days later scouts reported a large force of Indians and white men approaching Cobleskill. Patrick marched his men toward the invaders and spotted about twenty Indians. Against the advice of the local militiamen, he pursued them. The militiamen’s instinct was right: Patrick had led his men into an ambush. Musket fire burst out of the forest.

The ambushed soldiers and their foes took cover behind trees, firing at close range. Men fell on both sides. Patrick was fatally shot, as were two men trying to carry him away. The surviving Continentals and militiamen retreated, sprinting when they reached open ground. Five men sought refuge in a house. It was vacant, as were all the other houses, because people had run into the woods at the sound of musketry. The pursuers stopped to focus on killing the men in the house and burning it down.

The rest of the soldiers were able to flee while the raiders concentrated on plundering and then torching the houses. They also burned down barns, set haystacks afire, and killed or stole livestock. Militiamen recognized some of the white Loyalists, but Butler was not among them. Later a Tory accused of helping the raiders was shot dead while attempting to escape from members of a Committee of Safety. He was one of several Tories killed by frontier Rebels dispensing their own justice.

Of the estimated twenty-five raiders who were killed in the firefight, most were Indians. Militiamen arrived after the battle and buried the bodies of fourteen of Patrick’s soldiers. The bodies of the five men who had entered the house had been “Butchered in the most Inhuman manner,” a militia officer reported. Ten houses and barns were in ashes, and “Horses, Cows, Sheep &c. lay dead all over the fields.” A total of twenty-two defenders were reported killed and six wounded. At least two were captured, including a Continental officer—whose life was said to have been spared when Brant, a Mason, saw him giving the secret Masonic sign that was an appeal for help.

Until July 1778 Wyoming Valley remained untouched by the raiders—but not by bloodshed. For decades the area had been the battleground of a civil war between Pennsylvanians and people from Connecticut who had settled in the valley in 1754 and later founded Wilkes-Barre. They had based their claim on Connecticut’s 1663 charter, which gave the colony land as far westward as the Pacific Coast. What became known as the Yankee-Pennamite War was punctuated by small battles and some wanton killings. The feuding people of the valley setaside the land dispute at the beginning of the Revolution but were still divided as Rebels and Tories.

The bountiful valley was called the breadbasket of the Revolution, making it a prime military objective. The valley also had strategic value: If Butler and his Tory-Indian force could gain control of the valley, western New York and western Pennsylvania would be open to attack from Canada. And Wyoming Valley, rich in crops but scarce of people, looked particularly vulnerable to Butler. Because of its clouded political status, neither Pennsylvania nor Connecticut was clearly responsible for protecting the valley.

Late in June, Butler assembled about four hundred Rangers and Sir John Johnson’s green-uniformed King’s Royal Regiment, along with about five hundred Iroquois, for his biggest and boldest raid. The invasion began when an advance party of Indians attacked men working in fields. The Indians killed and scalped three of them and took two prisoners whom they later tortured and killed. Survivors of the attacks slipped away and carried news of the invaders to two of the forts.

The next day, July 1, two men at Fort Wintermoot, on the Susque-hanna opposite Wilkes-Barre, volunteered to scout the area for the invaders. Longtime residents and members of the family the fort was named after, they were trusted neighbors. They were also secret Tories, and their scouting was for Butler, not their neighbors. They led him to a good bivouac site near, but not visible from, the fort.

The Wintermoot scouts returned to the fort with an officer from Butler’s Rangers. The gates were opened, and the three entered. The officer, in Butler’s name, demanded surrender, promising that Butler would not harm the fort’s men, women, and children. One man moved to resist. His wife was at his side, grasping a pitchfork. But they stood alone. The fort was handed over to Butler, who later appeared with most of his force and made Fort Wintermoot his headquarters. A detachment of Rangers, including some who were former local residents, went to a second, smaller fort, which also surrendered.

The strongest fort in the valley, Fort Forty, along the banks of the Susquehanna, became the headquarters of the Patriots’ armed defenders. The fort was named after its builders, the forty settlers who had come from Connecticut in 1770 to press that colony’s claim for the valley. Now it sheltered hundreds of women, children, and armed men. When Butler demanded that Fort Forty surrender, the settlers gathered there refused to give up.

On July 3 they assembled a defending force: “two hundred and thirty enrolled men, and seventy old people, boys, civil magistrates, and other volunteers.” As they marched from the fort, three men came galloping up on exhausted horses. They were two Continental Army officers, Lt. Phineas Pierce and Capt. Robert Durkee, and Durkee’s black servant, Gershom Prince. They had ridden through the night to reach Fort Forty and report that a company of soldiers was on the way. Seeing the fort’s defenders heading out to battle, they realized that the rescue force would arrive too late.

Durkee and Prince, like many people of Wyoming Valley, had been born in Connecticut and later settled in the disputed Pennsylvania land. They, along with Gershom Prince, were veterans of the French and Indian War. They had served at Valley Forge and the Battles of Brandywine and Paoli. The three joined the defense force, which had left the fort not quite sure where or when the battle would be. Then they saw flames rising from Fort Wintermoot and headed toward it.

Butler, expecting the fire to lure a rescue force, had drawn them into a trap. As the Fort Forty force neared Wintermoot, they saw the invaders in a clearing, arrayed in a line for battle. Butler had taken off his uniform jacket and hat and wore a black kerchief knotted around his head. The defenders formed a line themselves and advanced.

Hidden Indian marksmen cut them down. Every company officer was mortally wounded or killed at the head of his men. Indian musketry, tomahawks, and war whoops set off a rout. Durkee, wounded, was dragged away by another Continental officer who had made it to Wyoming Valley in time for the battle. Seeing that the officer had a chance to flee, Durkee told him to run on alone. The officer joined a number of other officers and men who managed to escape. As Durkee lay dying, an Indian tomahawked and scalped him. Nearby was the body of Gershom Prince. Afterward a powder horn was found. Inscribed on it was

GARSHOM PRINCE HIS HORN MADE AT CROWNPOINT SEPTM. YE 3RD DAY, 1761 PRINCE NEGRO HIS HORNM.*

Butler, in his report on the “incursion,” wrote, “Our fire was so close, and well directed, that the affair was soon over, not lasting above half an hour, from the time they gave us the first fire till their flight. In this action were taken 227 Scalps and only five prisoners. The Indians were so exasperated with their loss last year near Fort Stanwix that it was with the greatest difficulty I could save the lives of those few … indeed the Indians gave no Quarter.” Left unsaid was the amount of bounty paid for each scalp. In enumerating the scalps taken, Butler confined his estimate to armed foes, but local people claimed that many unarmed men, women, and children had been killed.

Adam Crysler, a Loyalist friend of Brant who became a lieutenant in Butler’s Rangers, went beyond Butler’s casualty figure. In his journal Crysler wrote, “I went to Wyoming, New York, where we killed about 460 of the enemy.” By Patriot estimates about sixty invaders were killed, but Butler reported to Carleton the deaths of only one Indian and two Rangers.

After the rout Fort Forty surrendered. Under the surrender terms “property taken from the people called Tories” was to be returned, and the Tories themselves were to “remain in peaceable possession of their farms, and unmolested in a free trade throughout this settlement.”

Although Butler had promised that non-Tory homes would not be plundered, the raiders burned down every structure in sight. In his report he said he and his men “destroyed eight pallisaded Forts, and burned about 1000 Dwelling Houses, all their Mills &c., we have also killed and drove off about 1000 head of horned Cattle, and sheep and swine in great numbers, took away all the cattle they could drive, and killed the remainder.”

Butler later insisted that he could not control pillaging. Tales of looting, torture, and atrocities spread panic throughout the region. Survivors claimed to have seen a local Tory fatally shoot his Rebel brother as he attempted to surrender. He was one of the numerous men said to have been killed after asking for quarter—a long-honored plea for mercy. One of the stories told by survivors involved a regal Indian woman who ordered sixteen captured militiamen to sit in a circle, and then, passing behind them, smashed their skulls, one by one, with her war club. Men who survived the battle identified her as Queen Esther, a matriarch of Seneca and French descent well known in the valley. A powerful woman among the Seneca, she was given the title “queen” by settlers. One of her sons was identified as a raider.

After the attack people swarmed out of the area, clogging roads and crowding into boats to escape down the Susquehanna. “I never in my life saw such scenes of distress,” a Patriot wrote. “The river and roads leading down it were covered with men, women, and children fleeing for their lives.” A woman and her daughter, both widowed by the battle, walked all the way to their native Connecticut. Many other civilians temporarily fled into the marshes and mountains, where an unknown number died.

Washington soon learned what had happened at Wyoming Valley. He sent Col. Thomas Hartley, like Durkee a Pennsylvanian veteran of the Brandywine and Paoli battles, to the area of the raid. Hartley’s orders, as he described them, were “to make war on the savages of America instead of on Britain.” Leading about 250 men on a two-week expedition into Indian country near Wyoming Valley, Hartley killed at least ten Indians while losing four of his men. He rescuedsixteen persons captured by Indians in raids along the Susquehanna River and destroyed four Indian towns, including one said to have been ruled by Queen Esther. He also took about fifty head of cattle, twenty-eight canoes, and an assortment of items claimed to have been stolen by the Indians. To pay for the expedition he auctioned off his acquisitions, some of which had belonged to indignant people who had to bid for their own goods.

In September, Captain Brant and his Loyalist Indians reacted to Hartley’s war on the savages with an attack in the upper Mohawk Valley. Brant’s target was Andrustown, a fertile tract of farmland called the German Flats, after the immigrants whose axes had cleared the land. Brant especially despised Andrustown because many of its residents were militiamen who had killed his Indians at Oriska. The village was all but deserted; many of its fearful residents had moved closer to Fort Herkimer, returning to their farms only when they had to.

On September 17 a few people were in Andrustown gathering hay when a large group of Indians and Tories suddenly appeared. Indians fatally shot a father, his son, and another young man, then took their scalps. More raiders followed and, after ransacking the houses for booty, burned every building. Andrustown was never rebuilt. Details of the attack reached British headquarters in New York, where an intelligence officer noted, “Indians wanted to subdue German Flats … indeed at all times the Indians Scalped all the Rebels they met, but Joseph [Brant] restrained them.”

The following month an improvised force of Continentals and militiamen avenged Andrustown by attacking Brant’s headquarters, Unadilla. The large village, fifty miles west of German Flats, was at the confluence of the Susquehanna and Unadilla rivers. As soon as Brant and his Mohawks learned of the coming attack they abandoned Unadilla. “It was the finest Indian town I ever saw; on both sides of the River; there was about 40 good houses, Square logs, shingles & stone chimneys, good Floors, glass windows, etc.,” a Continental officer reported. The avengers burned the forty houses, torched two thousand bushels of corn, and destroyed a sawmill and a gristmill.

#

Vengeance would soon follow vengeance in the person of Capt. Walter Butler, John Butler’s son. Walter, the spy who had been captured by Benedict Arnold, had been held prisoner in Albany under a reprieved death sentence. He was first thrown into a nasty jail infamous for its wormy food. Then, after feigning illness, he was transferred to a private Albany home that happened to belong to a Tory. He easily escaped and rode off on a donated horse. Traveling by night and aided by Tories along the way, he reached Ranger headquarters at Niagara seething with a desire for revenge. While he had been a prisoner, Guy Carleton, citing Walter’s “loyalty, courage and good conduct,” appointed him a captain who was to “serve with the Indians.”

Walter’s choice for a raid, blessed by his father, was Cherry Valley, fifty miles west of Albany, and, like Wyoming Valley, a thriving farming region. Walter mobilized two hundred Rangers, fifty British Army volunteers, three hundred Seneca warriors, and three hundred of Brant’s Volunteers, a mix of whites and Indians. Brant led them reluctantly because, as a veteran leader, he resented being under young Walter’s command.

By the time a typical raid began, people, warned beforehand, had fled to safety in a fort, leaving nearby houses virtually deserted. But this raid was a surprise, and the makeshift fort guarding the area was ill prepared. Many civilians and officers—including the fort commander, Col. Ichabod Alden—lived in cabins outside the fort. Alden had ignored warnings that an attack was imminent.

On November 10, 1778, the raiders arrived silently, shrouded in a thick fog that rose from the snow-covered ground. While some attacked the fort, others surrounded the cabins, killing Alden and other officers as they rushed out to defend the fort. The raid turned into a rampage. One officer had boarded with Robert Wells, a judge who had been a close friend of Walter Butler’s father. After killing the officer, raiders slew Wells, his wife, his brother and sister, three sons, and his daughter. Judge Wells was said to have been killed by a Loyalist who knew him, perhaps Walter Butler himself.

People in the fort could hear screams and see flames rising from cabins and barns. The next day, after the attackers had left, men were sent out from the fort to bring in the dead. “Such a shocking sight my eyes never beheld before of savage and brutal barbarity,” one of the officers wrote in his diary. He saw a “husband mourning over his dead wife with four dead children lying by her side, mangled, scalpt, and some their heads, some their legs and arms cut off, some torn the flesh off their bones by their dogs—12 of one family killed and four of them burnt in his house.” There were thirty-two bodies of civilians, most of them women and children. Sixteen soldiers were also killed. The burning of the valley left 182 settlers homeless.

The murders were blamed on Indians, but survivors said they saw Loyalists amid the carnage. A man identified as a Tory sergeant named Newbury was seen murdering a young girl by driving a tomahawk into her skull.42 In a letter to Major General Schuyler of the Continental Army, Walter Butler later denied responsibility for the murders: “I have done everything in my power to restrain the fury of the Indians from hurting women and children, or killing the prisoners who fell into our hands.” He went on to make his prisoners essentially hostages to the fate of his mother and young siblings, who had been held by the Patriots ever since Walter and his father fled to Canada in 1776.

“I am sure you are conscious that Colonel Butler or myself have no desire that your women or children should be hurt,” he continued in the letter. “But, be assured, that if you persevere in detaining my father’s family with you, that we shall no longer take the same pains to restrain the Indians from prisoners, women and children, that we have heretofore done.” Schuyler had been relieved of his commission, so the letter was answered by Brig. Gen. James Clinton, who referred to what Butler had written as a threat. But Clinton began making the arrangements that would eventually send Mrs. Butler and her children to a reunion with John Butler.

#

Stirred by outcries over the Wyoming and Cherry valley raids, Congress directed Washington to send the Continental Army against the Indians and their Tory allies. Washington responded by ordering what would be history’s first large-scale attack on Indians by an American armed force. He put Maj. Gen. John Sullivan in command of an expedition “against the hostile tribes of the Six Nations of Indians, with their associates and adherents.”

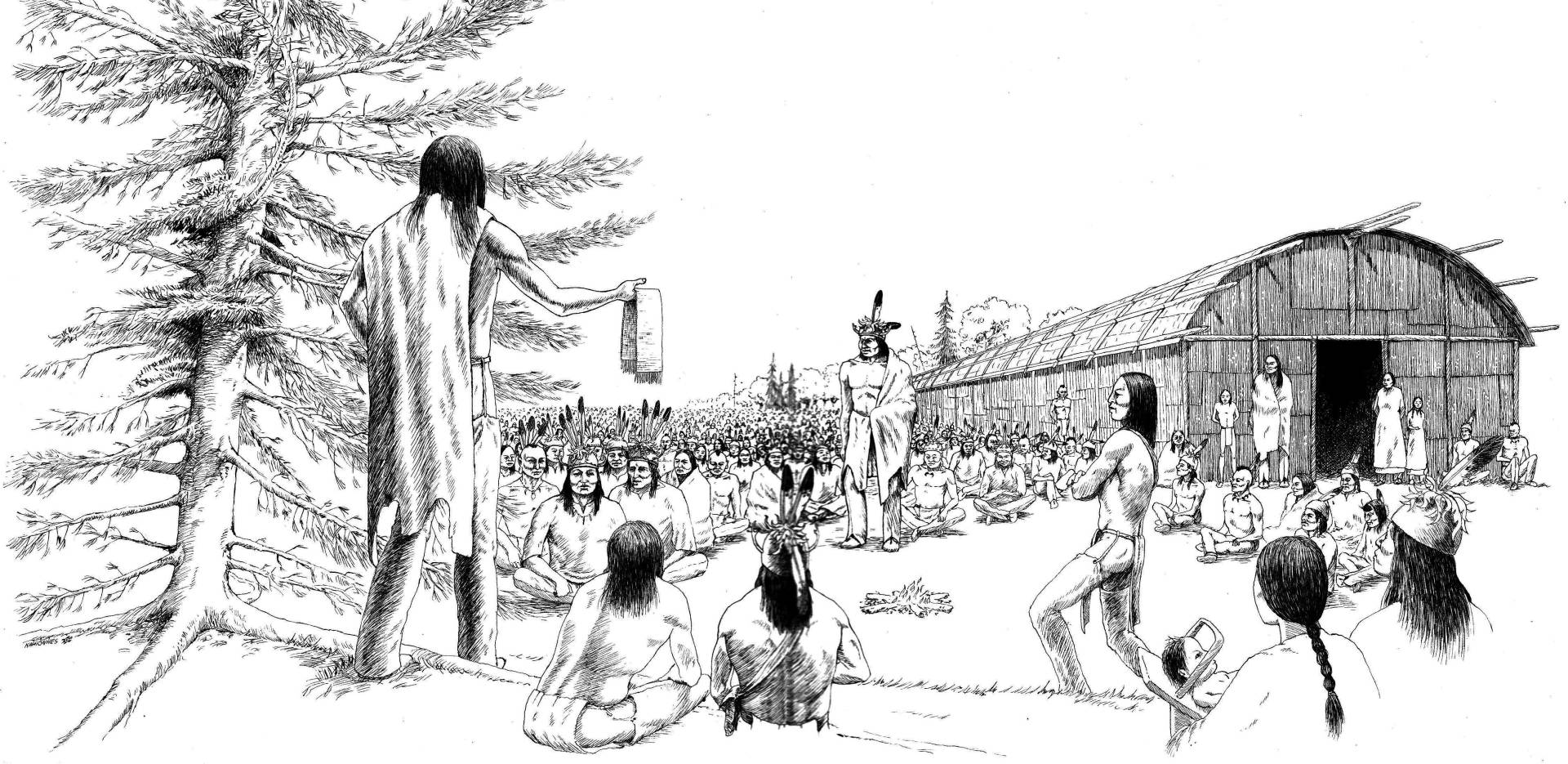

Washington ordered “the total destruction and devastation of their settlements, and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground & prevent their planting more.” He went on to suggest that his attacks be “attended with as much impetuosity, shouting, and noise, as possible” and that the troops “rush on with the war-whoop and fixed bayonet. Nothing will disconcert and terrify the Indians more than this.” If any Indians tried to negotiate a peace, he said, they were to be dealt with only if they showed their sincerity “by delivering up some of the principal instigators of their past hostility into our hands: Butler, Brant, the most mischievous of the Tories.” Sullivan led more than twenty-three hundred troops, most of them Continentals. At an Indian village called Tioga Point (now Athens, Pennsylvania), he rendezvoused with Brigadier General Clinton, who added his fourteen hundred Continentals to the campaign of retribution and destruction. On the Fort Pitt frontier to the west, a third, smaller expedition was ordered to head up the Allegheny River valley to begin a similar slash-and-burn foray against the western villages of the Six Nations.

While Clinton was in Canajoharie, New York, waiting for his troops to assemble, local militiamen captured two Butler Rangers—Sgt. William Newbury and Lt. Henry Hare—lurking near Clinton’s troops. The spies had lived in the area until they went off with recruiting parties to Canada. Tried by a court-martial, they were found guilty and sentenced to death for spying. The hangings, Clinton wrote his wife, “were done … to the great satisfaction of all the inhabitants of that place who were friends of their country, as they were known tobe very active in almost all the murders that were committed on the frontiers.” Before being hanged, Newbury, the father of six, confessed to the tomahawk slaying of a young girl during the Cherry Valley raid. Hare admitted that he had killed and scalped one of the girls slain outside Fort Stanwix in 1777.