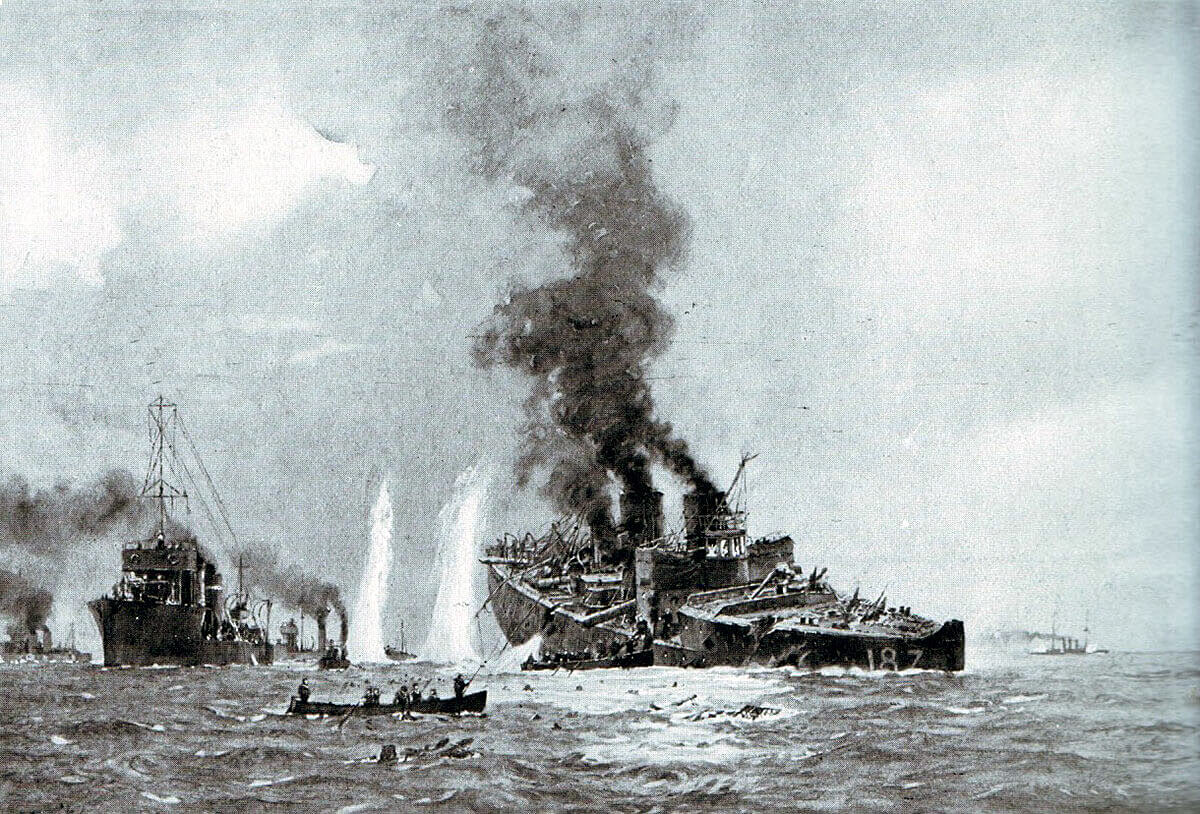

German destroyer V187 sinking during the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War.

The situation was further complicated by the weather; as the British forces steamed eastward, a thickening fog reduced visibility. First contact came just before 7.00 am, when the 1st Flotilla sighted the German destroyer G 194, which made off southeast, pursued by Laurel and three others of the 4th Division. Hipper, on receiving the news, issued an order to the light cruisers Stettin and Frauenlob to ‘hunt destroyers’; the other light cruisers were ordered to raise steam. Tyrwhitt turned to follow Laurel and the others; meanwhile other German destroyers were steering parallel with Arethusa. The German destroyers, the V Flotilla, were soon suffering from engineering problems as they were unprepared for high speed operations; their speed dropping, they called for cruiser support, of which the first elements, in the form of Stettin and Frauenlob, arrived at 7.57 am.

Fearless engaged Stettin, scoring one hit before the German light cruiser turned away, principally to raise steam in all her boilers; Fearless turned SSW to follow Arethusa. Tyrwhitt’s flagship was engaging Frauenlob, and having rather the worst of it, suffering 15 direct hits on the side and waterline and many inboard. However she hit Frauenlob 10 times before turning away to the west; her adversary did not follow, retiring south eastward. While this was occurring Keyes, to the north west, had sighted two four funnelled cruisers which he supposed to be hostile, being still unaware of Goodenough’s presence.

At 8.20 am Fearless and her destroyers sighted the isolated German destroyer V187. Attempting to outrun the 5th Division of destroyers sent by Blunt to pursue her, V187 found herself steaming directly towards Lowestoft and Nottingham, detached by Goodenough to support Tyrwhitt. V187 executed a 180 degree turn, but now encountered the rest of Blunt’s flotilla. Within a few moments she was fatally damaged; her remaining gun fired at and hit Goshawk.. At 9.10 am V187 went down. As several boats from the British destroyers moved towards the survivors in the water Stettin reappeared; Captain Nerger was unaware that rescue operations were in progress, as he later reported:

At 9.06 am eight destroyers were sighted bunched together. I at once signalled the Admiral commanding the Scouting Forces, ‘Am in action with flotilla in square 133,’ turned to port and opened fire at 7200 metres. The first salvo straddled and thereafter many hits were observed. While most of the destroyers scattered, two remained on the spot, apparently badly damaged, but were soon lost to sight in the mist.

In addition to Stettin and Frauenlob, Hipper had also ordered Köln and Strassburg from Wilhelmshaven and Mainz from Ems to put to sea, while the elderly Hela and Ariadne, which had been on patrol, were also at sea. Köln was the flagship of Rear Admiral Leberecht Maass, the commander of the II Scouting Group. In addition, Hipper put three further light cruisers on standby, being Stralsund, Danzig and München. At this time Hipper was unaware of the presence at sea of Beatty’s battlecruisers, but at 8.50am he asked Ingenohl: ‘Will you permit Moltke and Von der Tann to leave in support as soon as it is clear?’ Pondering this. Ingenohl replied at 9.08 that the battlecruisers would be released only when the full strength of the British was known, subsequently authorising the sortie.24 As Eric Osborne points out, however, the exchange was academic. That day, the tide was particularly low, and the depth of water over the Jade Bar was at 9.33 only twenty six feet. Both battlecruisers drew over twenty six feet, and would in any case not be able to pass the bar before noon. Two battleships, Heligoland and Thüringen were outside the bar; but Ingenohl refused to allow them to weigh anchor.

Meanwhile at 8.55am Fearless had come up with the badly damaged Arethusa, and with her steamed slowly west south west, while the flagship’s crew worked desperately to repair some of the damage. Hearing from Keyes at 9.45 that he was being chased by enemy cruisers (in fact Goodenough’s light cruisers) Tyrwhitt turned back towards Heligoland. His speed, however, was down to ten knots and he soon realised that Keyes had in fact seen Goodenough’s ships, so he turned again and then, at 10.20, stopped to continue the repair work, Fearless and the 1st Flotilla remaining with him while the 3rd Flotilla continued to the westward.

Anxious to get to grips with the enemy, Maass did not wait to concentrate what would, united, have been a powerful force of light cruisers. His failure to do so was his undoing. He was unaware of Beatty’s presence at sea, or even that of Goodenough. When he left Wilhelmshaven he did so in clear weather with good visibility; in the Bight, however, there was a thick fog, which also delayed Mainz as it left the Ems estuary. None of the German units involved had warned Maass of this. In Köln he steamed northwest, which so far as he knew was the direction in which to find the British, while Strassburg steamed west north west aiming at what was taken to be the flank of the British fores. Mainz was ordered to pursue a course NNE to aim at Tyrwhitt’s rear.

At 10.55 Strassburg sighted Arethusa and Fearless through the mist, and opened fire. Tyrwhitt considered his force outgunned and turned away southwest, launching a destroyer attack on the German light cruiser. As it turned away, to avoid the torpedoes, all of which missed, it lost contact with Tyrwhitt’s ships; Captain Retzmann decided not to renew the action because of the risk of further torpedo attacks. Next on the scene was Köln: the brief engagement that resulted followed the pattern of that involving Strassburg. Significantly, however, Tyrwhitt identified Köln as an armoured cruiser of the Reon class, and radioed Beatty for support. The latter’s immediate reaction was to order Goodenough to detach two more light cruisers; but Goodenough decided to head for Tyrwhitt with all four remaining ships of his squadron.

Strassburg now reappeared, and brought Arethusa and Fearless under such heavy fire that Blunt followed up Tyrwhitt’s previous appeals with another message to Beatty: ‘Assistance urgently required.’27 It was about 11.30am. Beatty was at this time about forty miles north west of Tyrwhitt’s force, and he had an immediate and difficult decision to take, which he discussed with Chatfield, his Flag Captain:

The Bight was not a pleasant spot into which to take great ships; it was unknown whether mines had been laid there, submarines were sure to be on patrol, and to move into this area so near to the great German base at Wilhelmshaven was risky. Visibility was low, and to be surprised by a superior force of capital ships was not unlikely. They would have had plenty of time to leave harbour since Tyrwhitt’s presence had been first known. Beatty was not long making up his mind. He said to me, ‘What do you think we should do? I ought to go and support Tyrwhitt, but if I lose one of these valuable ships the country will not forgive me.’ Unburdened by responsibility, and eager for excitement, I said, ‘Surely we must go.’ It was all he needed but whatever I had said would have made little difference.

Beatty turned his squadron to the south east, at a speed of 26 knots. At 11.45 he altered course to ESE, increasing speed to 27 knots, signalling to Blunt that he was coming to his support.

Meanwhile Mainz had arrived, and had begun engaging the destroyers of the 1st Flotilla. Just as she threatened to inflict serious damage, however, Goodenough appeared. Mainz at once turned away, as her first lieutenant later described:

Immediately on identifying three cruisers of the ‘Town’ class ahead of us the helm of the Mainz was put hard over to starboard, but even in the act of turning the enemy’s first salvos were falling close to us and very soon afterwards we were hit in the battery and the waist.

As she headed south at her maximum speed, Mainz sighted Fearless with six destroyers. Opening an accurate fire, she disabled Laurel, and then concentrated on Liberty, hitting her twice, and wrecking her bridge and killing her captain. Transferring her fire to Lysander and Laertes, she hit the latter with a salvo of six shells, hitting her boilers and bringing her to a standstill. It was an impressive demonstration of what would have been the vulnerability of Tyrwhitt’s force had it not been so heavily supported.

By now, however, Goodenough’s cruisers had again caught up with Mainz, and subjected her to a furious cannonade. Briefly, Mainz disappeared into the mist, and was almost at once torpedoed by the destroyer Lydiard; when she became visible to Goodenough’s cruisers, she was lying nearly stopped. Lieutenant Stephen King-Hall, in Southampton, described Mainz’s fate:

We closed down on her, hitting with every salvo. She was a mass of yellow flame and smoke as the lyddite detonated along her length. Her two after funnels melted away and collapsed. Red glows, indicating internal fires, showed through gaping wounds in her sides. At irregular intervals one of her after guns fired a solitary shot, which passed miles overhead. In ten minutes she was silenced and lay a smoking, battered wreck, her foremost anchor flush with the water. Ant-like figures could be seen jumping into the water as we approached. The sun dispersed the mist, and we steamed slowly to within 300 yards of her, flying as we did so the signal ‘Do you surrender?’ in International Code. As we stopped the mainmast slowly leant forward, and, like a great tree, quite gradually lay down along the deck. As it reached the deck a man got out of the main control top and walked aft – it was Tirpitz junior.

At 12.25pm Goodenough ordered ‘cease fire’ and Lurcher went alongside the stricken cruiser to rescue survivors. Keyes, seeing one young officer remaining on the poop after superintending the removal of the wounded, called to him and held out his hand to help him:

But the boy scorned to leave his ship as long as she remained afloat, or to accept the slightest favour from his adversary. Drawing himself up stiffly, he stepped back, saluted, and answered: ‘Thank you, no.’

At 13.10 Mainz went down, the survivors in the water being picked up by Firedrake and Liverpool. Among them were the young officer and also Lieutenant Wolf von Tirpitz. When the latter came aboard Liverpool, he was grateful for his courteous reception:

They offered us clothes while our own were drying in the engine room. We were given port wine and allowed to use the wardroom. Only the sentries before the door reminded us that we were prisoners. Shortly after I came on board the captain sent for me and read me a wireless signal from his admiral: ‘I am proud to be able to welcome such gallant officers on board my Squadron.’ I repeated this message to my comrades. It cheered us up, for it showed that Mainz had made an honourable end.’

By now, Beatty’s battlecruisers were arriving on the scene. Almost at once, Strassburg turned away; but Köln turned too late, and for seven minutes presented an unmissable target for the main armament of the battle cruisers, which inflicted terrible damage on her. She was given a reprieve when Ariadne, steaming for the sound of the guns, appeared. Lion shifted her fire to the elderly cruiser, and her consorts joined in; Ariadne lurched away, a mass of flame and smoke. Beatty, anxious to keep his ships concentrated, and fearful of reported mines in the vicinity, also turned away and went to finish off Köln. Ariadne stayed afloat until 3.10pm by which time Danzig had arrived to take off survivors.

Beatty soon found Köln again, sighting her at 1.25pm. Lion’s first salvo smashed the armoured conning tower, the steering gear, and the engine rooms. Chatfield watched her destruction:

She bravely returned our fire with her little four-inch guns aiming at our conning tower. One felt the tiny four-inch shell spatter against the conning tower armour, and the pieces ‘sizz’ over it. In a few minutes the Köln was also a hulk.

Köln sank within ten minutes; of her crew of five hundred men only one, a stoker, survived. Beatty now ordered all the British forces to withdraw, particularly keen to get the damaged vessels away as quickly as possible.

At 2.25 Moltke and Von der Tann, under Rear Admiral Tapken, belatedly arrived on the scene; Ingenohl had ordered them ‘not to become engaged with the enemy armoured cruiser squadron,’ and Hipper had instructed Tapken in any case to wait until he himself arrived in Seydlitz, an hour behind. When he arrived, the three battle cruisers, with Kolberg, Stralsund and Strassburg, began a search for the missing cruisers, but it was soon evident to Hipper that they must have gone down, and at 4.00pm he turned for home.

Tyrwhitt, in the crippled Arethusa, limped homeward until 7.00pm when her engines failed, and he had to radio for assistance, which arrived in the form of the armoured cruiser Hogue at about 9.00pm, and which took her in tow. As she entered the Nore, Arethusa was cheered all the way. At Sheerness, Churchill came aboard and, as Tyrwhitt described, ‘fairly slobbered’ over him. The victory, such as it was, had come at just the right moment to confirm the public belief in the supremacy of the Royal Navy. Beatty wrote to his wife to tell her of the victory:

Just a line to say all is well. I sent Liverpool in to Rosyth today with some prisoners and wounded. We got at them yesterday and got three of their cruisers under the nose of Heligoland, which will have given them a bit of a shock. The ones in the Liverpool were all that were saved out of one ship and, alas, none were saved from the others that sank. The 3rd disappeared in fog in a sinking condition and I doubt if she ever got back. I could not pursue her further, we were too close already and the sea was full of mines and submarines, and a large force might have popped out on us at any moment. Poor devils, they fought their ships like men and went down with colours flying like seamen, against overwhelming odds.

Beatty’s euphoria did not last long; by September 2 he was complaining bitterly to his wife at the lack of any commendation from the Admiralty:

I had thought I should have received an expression of their appreciation from Their Lordships, but have been disappointed, or rather not so much disappointed as disgusted, and my real opinion has been confirmed that they would have hung me if there had been a disaster, as there very nearly was, owing to the most extraordinary neglect of the most ordinary precautions on their part. However, all’s well that end’s well, and they haven’t had an opportunity of hanging me yet and they won’t get it.

In fact, Beatty did subsequently get his commendation in the form of a letter from the Admiralty on October 22, expressly referring to ‘the risks he had to face from submarines and floating mines’ in bringing his force into action.

The defeat imposed even greater caution on the German high command, and the Kaiser issued a personal order that no operations involving the heavy units of the fleet were to be carried out without his express permission. Admiral von Müller laconically noted in his diary for August 29:

Tirpitz is beside himself. The Kaiser was swift with his reproaches: carelessness on the part of the Fleet, inadequate armour of the cruisers and destroyers. Pohl was shrewd and championed the Fleet.

Immediate precautions were taken to strengthen the German defences. Two large minefields were laid to the west of Heligoland, which Scheer recorded as being effective, and in conjunction with improved weaponry such as aircraft and anti submarine equipment ‘kept the inner area so clear that the danger from submarines came at last to be quite a rare and exceptional possibility.’37 He was, however, concerned that the Heligoland Bight raid was merely a precursor to a more ambitious offensive move; the defensive posture imposed on the High Seas Fleet must make such a British move much more dangerous:

To anticipate it was therefore obvious that our High Command would desire greater freedom of movement in order to have a chance of locating parts of the enemy forces. This could only be done if the light forces sent out ahead could count on timely intervention by the whole High Seas Fleet. On the other hand, it was not the Fleet’s intention to seek battle with the English Fleet off the enemy’s coasts. The relative strength (as appeared from a comparison of the two battle lines) made chances of success much too improbable.

Keyes and Goodenough put the outcome of the battle in perspective, both regarding it as having been a missed opportunity. The former wrote that ‘an absurd fuss was made over the whole affair … It makes me sick and disgusted to think what a complete success it might have been but for, I won’t say dual – but multiple control.’ At the Admiralty Captain Herbert Richmond was even more scathing:

Anything worse worded than the order for the operations of last Friday [August 28] I have never seen. A mass of latitudes and longitudes, no expression to show the object of the sweep, and one grievous error in actual position, which was over 20 minutes out of place. Besides this, the hasty manner in which, all unknown to the submarines, the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron suddenly turned up in a wholly unexpected direction, thereby running the gravest dangers from our own submarines. The weather was fairly foggy, ships came up on one another unexpectedly, and with such omissions and errors in the plan it was truly fortunate that we had no accidents.

Richmond was thoroughly discontented with the Admiralty’s general policy at this time, writing in his diary on September 4:

If we go on like this the North Sea deserves its other name of German Ocean. It is the German Ocean at this moment. Only those fatuous and self-satisfied creatures, Sturdee and Co, with their sprinkling of undigested knowledge, can think it a sea in which we retain or have any command.