The Livonian Brothers of the Sword were a military order established by their second bishop, Bishop Albert of Riga, in 1202. Pope Innocent III sanctioned the establishment in 1204 for the second time. The membership of the order comprised German “warrior monks”. Following their defeat by the Samogitians and Semigallians in the Battle of Schaulenin 1236, the surviving Brothers merged into the Teutonic Order as an autonomous branch and became known as the Livonian Order.

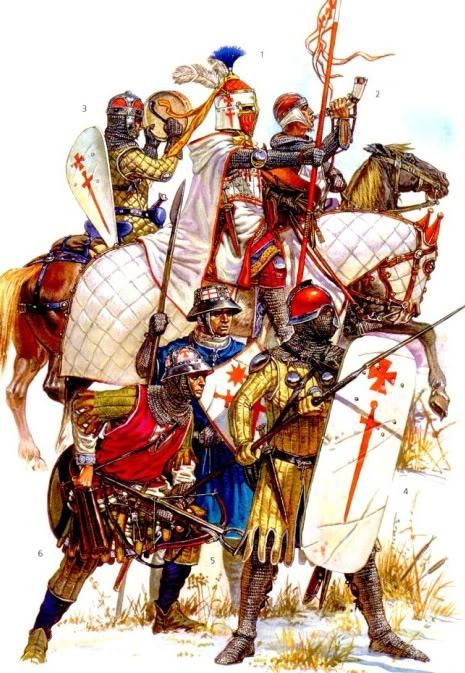

The first military order in the Baltic region, founded in Livonia in 1202 on the model of the Templars and absorbed into the Teutonic Order in 1237. The order’s original Latin name was the Fratres Milicie Christi de Livonia (“Brethren of the Knighthood of Christ of Livonia”); the more usual modern name Sword Brethren or Sword Brothers (Ger. Schwertbrüder) corresponds to the Middle High German designation Swertbrudere, which derives from the knights’ insignia of a sword beneath a red cross, which they wore on their white mantles.

According to the chronicler Henry of Livonia, the initiative for the new order came from the Cistercian Theoderic, a veteran in the Livonian mission. However, its establishment is often attributed to the newly ordained bishop of Livonia, Albert von Buxhövden (1199-1229), under whose obedience the order was placed. The foundation has to be seen against the background of the disastrous lack of military resources that had cost the life of the previous bishop, Berthold of Loccum (1197-1198). A permanent army in the region to supplement the unpredictable arrival of seasonal crusaders and garrison the castles must have been seen as necessary in order to control the newly converted and conquered territory. In 1204 both Bishop Albert and Pope Innocent III gave their approval of the order. The same year it began to establish itself in its first convent in Riga under its first master, Winno (1204-1209).

Organization

The Sword Brethren lived according to the Rule of the Templars. They consisted of three classes: knight brethren, priests, and service brethren. A general assembly of the knight brethren was in principle the highest decision-making body, but in practice the master, elected for life by the assembly, was in charge of the order, with an authority comparable to that of the abbot of a Cistercian monastery. Under him served a vice-master who also deputized for him in his absence. A marshal took care of the order’s military affairs and led it in battle, while a treasurer was in charge of finances. Provincial masters were placed in charge of new castle convents, each of which included a priest and a number of knight brethren, service brethren, and mercenaries. Advocates served as local administrators on the order’s estates and acted as its link to the local population. Also associated with the order were a number of secular vassals who were enfeoffed with lands on its territory. They were mainly recruited from immigrant German nobles, but also, at least in some cases, from among the native nobility.

Even in its heyday, that is from around 1227 to 1236, the order probably had only some 110 knight brethren and perhaps 1,200 service brethren; with approximately 400 knights and soldiers supplied by its secular vassals, the order could at best field an army of some 1,800 men, in addition to local Livonian auxiliaries [Benninghoven, Der Orden der Schwertbrüder, pp. 223-224, 407-408]. During that time the order had a convent in Riga, convent castles in Ascheraden (mod. Aizkraukle, Latvia), Fellin (mod. Vijandi, Estonia), Reval (mod. Tallinn, Estonia), Segewold (mod. Sigula, Latvia), and Wenden (mod. C? sis, Latvia), and also lesser strongholds in Adsel (mod. Gaujiena, Latvia), Wolmar (mod. Valmiera, Latvia), and Oberpahlen (mod. Poltsamaa, Estonia).

Early History: Establishment of the Order

The Sword Brethren had their first experience of local warfare in the winter of 1204-1205, when they joined the Semgallians in an ambush of a Lithuanian force returning from a raid into Estonia. In the following years the order soon proved its worth in battle, not least when it defeated a rebellion of the Livonians, centered on the fortress of Holm (1206).

Despite the obedience it owed to the bishop of Riga, the order was soon able to act on its own initiative, and throughout its short lifespan it continuously struggled to achieve independence from the church of Riga. It was important for the order to secure an independent territorial power base and financial resources, and it claimed part of the territory that was being conquered in conjunction with the forces of the bishop and the seasonal crusaders. This claim soon led to a conflict with Bishop Albert in respect of the division of the conquests and the terms on which the order held its territory, convents, and castles. In this struggle the balance of power constantly shifted, as seasonal crusaders left Livonia and Bishop Albert had to leave for Germany to recruit new crusaders, as occurred approximately every second year.

When Albert returned from Germany in 1207, the Sword Brethren demanded the right to retain a third of all future conquests. This initiative on the part of the order may well have resulted from a stay in Riga of the Danish archbishop of Lund in 1206-1207. The order may have seen a possibility of playing the Danish primate off against Bishop Albert by threatening to acknowledge the primacy of the archbishopric of Lund. Under pressure, Albert reluctantly agreed to assign new territory to the order, but in the case of the lands already conquered he tried to exclude the order from the core region along the river Düna. This was probably not a wise move, since as a result the Sword Brethren now looked north toward Estonia. Soon the order was able to establish its second convent and castle, Segewold, close to the Livish stronghold of Treiden (mod. Turaida, Latvia). A third convent was founded around the same time in Nussburg at Wenden deep in Lettish territory. These foundations enabled the order to push on into Estonian territory in 1208 independently of Bishop Albert. It suffered a momentary setback in 1209, when Master Winno was killed in an internal power struggle, but with the election of Volkwin (1209-1237) as its second master, the order quickly managed to reestablish stability in its leadership.

In the continued struggle for supremacy, both parties appealed to Pope Innocent III, who in October 1210 decreed that in the future the order was to retain one-third of conquered territory. In July 1212 the Sword Brethren received imperial confirmation of this privilege and were also promised free possession of the Estonian provinces of Ugaunia and Sakkala. This was undoubtedly a victory for the order and may be seen as the beginning of its state in Livonia. Bishop Albert received some compensation, when (probably in 1211) the pope authorized his ordination of new bishops in Livonia and soon after refused the order’s request to have the same right in its own territory (1212). However, Innocent III compensated for this in 1213 by confirming the order’s possession of Sakkala and Ugaunia and also authorizing Anders Sunesen, archbishop of Lund, to ordain bishops in these provinces. Albert of Buxhövden’s decision to ordain Theoderic as bishop of Estonia (1211) can only be seen as an attempt to curb the order’s designs in Estonia. Yet the advantage gained was soon lost, when Innocent III in 1213 decreed that Theoderic henceforth was to be subject only to the pope or his legate to the region, who happened to be Anders Sunesen.

The final effort to subdue the pagan Estonians began in 1215, initially with the order as its driving force. Having defeated the Estonians at Fellin in 1217, the order now dominated both the northern part of Livonia and a large part of Estonia. The threat this posed to the position of Bishop Albert prompted him to appeal in person to King Valdemar II of Denmark for help in 1218. The king obliged by sending a large fleet to Estonia the following year. Despite initial difficulties, the Danes managed to conquer the remaining northern provinces of Estonia in the summer of 1219, with the exception of the island of Ösel (mod. Saaremaa, Estonia).

The Danish crusade may have come as a surprise to the order, and in 1220 a diplomatic crisis arose when the order raided Harria. The Danes declared that, according to an agreement with the Livonian church, all of Estonia belonged to them and asked the order to hand over the hostages it had taken. Master Volkwin complied and subsequently decided to enter into an agreement with the Danes, which formally divided Estonia between them: the Danes kept the northern provinces, including the still unconquered island of Ösel, while the order received the southern provinces. In this way the order presumably hoped to avoid handing two-thirds of its conquest over to the church in accordance with the ruling of 1210. There was, however, a certain division of opinion within the order as to the wisdom of this, and later in the year it did decide to allot the church its two-thirds. Yet faced with an alliance between the order and the Danes and a Danish blockade of crusader ships embarking from Lübeck, Bishop Albert in March 1221 found himself forced to recognize Danish overlordship not only in Estonia but also in Livonia. This opened new possibilities for the order to throw off its obedience to the bishop and replace it with a link to the distant Danish king and church.

Order Domination

The scene was now set for a complete Danish takeover in the Baltic region, although this domination was to prove short-lived. After the Danes had gained a foothold on Ösel and established a stone fortress there, Valdemar II left Estonia in 1222; according to Henry of Livonia, he gave up the royal rights in Sakkala and Ugaunia to the order and spiritual rights to Bishop Albert in return for their perpetual fealty. Soon afterward, however, an uprising broke out on Ösel, and the Christian forces were unable to hold the fortress. In the following winter, the Osilians joined mainland Estonians in defeating local Danish forces before unleashing a successful attack on Fellin in January 1223. The order was taken by complete surprise and suffered heavy losses as stronghold after stronghold fell, until only the castle in Reval remained in Christian hands.

To make matters worse, Valdemar II and his eldest son were kidnapped in May 1223 by one of his vassals. They remained prisoners for two years, while the Danish Empire collapsed. To survive in Estonia, the order now had to rely on help from the Livonian church. The situation began to stabilize with the recapture of Fellin by the combined forces of the order and Livonian bishops, and the return of Bishop Albert from one of his recruitment tours with a substantial crusader army. By the end of 1224 the insurgents had to surrender. For the order, however, the events of 1223-1224 meant that the balance of power had changed significantly in favor of Bishop Albert and the Livonian church. With the Danes neutralized, the order had to agree to a new division of Estonia with the bishops, so that the order retained little more than one-third of the territory.

Hoping to perpetuate his ascendancy over the order, Bishop Albert in 1224 asked Pope Honorius III to dispatch a legate to the region to settle the territorial organization of Livonia on the current basis. This, however, proved to be a miscalculation on Albert’s part. When the legate, William of Modena, arrived in 1225 he had no intention of favoring the Livonian church. When Albert’s brother, Bishop Hermann of Leal (mod. Lihula, Estonia), who was now also lord of Dorpat (mod. Tartu, Estonia), together with local vassals seized some of the Danish possessions, William ordered these and the remaining Danish possessions to be transferred to himself as the pope’s representative.

Many of William’s other initiatives were designed to strengthen both the city of Riga and the Sword Brethren, and it was Bishop Albert and his colleagues who were disadvantaged. Now the city was allowed to gather crusaders under its banner, and it was also entitled to one-third of future conquests so that the church, originally allocated two-thirds of conquests, was left with only one-third. At the same time the order received a number of privilegies and exemptions for its church in Riga (the Church of St. George). This allowed the Sword Brethren to play a far greater role in the internal life of Riga, where they could now compete for the favors of visiting and established merchants. William also allowed the Sword Brethren to accept seasonal crusaders into their forces. This was important because many crusaders preferred to fight along with the order rather than the bishop.

These changes made the city of Riga the natural ally in the order’s continued rivalry with the bishops, and in 1226 the order and city formalized their collaboration in an alliance of mutual assistance, whereby brethren became “true” citizens of Riga, while members of the upper strata of burgesses could join the order as confratres (lay associates).

When William of Modena left later in 1226, the territories he had held were transferred to his deputy and vice-legate, Master John. However, when the population of Vironia revolted again, John could only quell the uprising with the help of the Sword Brethren, who then went on to expel the remaining Danes from Reval. When John in turn left the region in 1227, he handed over all his territories to the order, so that it now controlled Revalia, Harria, Jerwia, and Vironia. To strengthen the legitimacy of its possession of the former Danish provinces, the order acquired a letter of protection from Henry (VII), king of Germany, in July 1228. Despite a devastating defeat in 1223 as a result of William of Modena’s first legatine mission, the Sword Brethren had emerged as the leading power in Livonia.

Between Pope and Papal Legate

A new chapter in the order’s history began when the Cistercian Baldwin of Aulne arrived in Livonia in 1230 as vicelegate charged with resolving the conflict that had arisen over the succession to the bishopric of Riga after the death of Bishop Albert in 1229. Soon, however, Baldwin began to involve himself in wider Livonian affairs. He came into conflict with the Sword Brethren over the former Danish provinces, which he claimed the order held illegally; with reference to William of Modena’s earlier ruling, Baldwin demanded that they should be transferred to him. Faced with resistance from the local powers, Baldwin left for the Curia, where, in January 1232, he managed to have himself appointed as bishop of Semgallia (a title created for the occasion) and full legate with far-reaching authority. During the summer of 1233, Baldwin returned with a crusader army with which to bolster his demands. An army was sent to Estonia, where the Sword Brethren were ordered to surrender their territories and castles.

The order was divided over how to react to Baldwin’s demands. Master Volkwin was in favor of yielding to Bald win, but was temporarily deposed and imprisoned. The interim leadership decided to fight the legatine army, which in the ensuing battle in September 1233 was annihilated on the Domberg in Reval. The order speedily dispatched a delegation to the Curia in order to defend its action against the pope’s legate. It succeeded to the extent that in February 1234 Pope Gregory IX decided to recall Baldwin and replace him as legate by William of Modena, who soon persuaded the pope to annul all of Baldwin’s initiatives. But at the Curia Baldwin persuaded the pope in November 1234 to summon all his adversaries to answer a formidable list of charges. The order was accused of having summoned heretic Russians and local pagans to fight against the bishop and church of Leal, a charge that could have made the order itself a target of crusades.

In a trial at Viterbo during the spring of 1236, the order was largely exonerated. However, the king of Denmark had also begun to lobby for the return of the former Danish provinces. On this point Gregory IX supported the Danes and ordered Revalia, Jerwia, Vironia, and Harria to be given back to the Danish king. To comply would seriously have reduced the power base of the Sword Brethren, and it is doubtful whether they were prepared to do so. In the event, the order did not survive long enough for this to become evident.

Defeat and Unification with the Teutonic Order

During the 1230s the Sword Brethren had begun to direct their attention toward Lithuania, now seen as the greatest threat to Christianity in the Baltic region. This was a sentiment shared by the Russians of Pskov, with whom the order now often allied itself. In the summer of 1236, a substantial number of crusaders had arrived in Riga eager for action. Perhaps against its better judgment, the order was persuaded to organize a raid into Lithuanian territory involving both local forces and Pskovians. At a place called Saule (perhaps mod. Siauliai, Lithuania), the Christian forces suffered a crushing defeat on 22 September 1236. Probably only a tenth of the Christian force survived, and among the casualties were Master Volkwin and at least 49 knight brethren. The existence of the order was not immediately threatened. It still held its castles and had a substantial number of vassals, particularly in the northern parts of Estonia. But it was hardly in a position to raise another army for separate actions, and in the south the order had to fear Lithuanian retaliations.

Consequently, the order had to speed up negotiations that were already in progress concerning a merger with the Teutonic Order. With its bargaining power now reduced by military defeat, the representatives of the order had no choice but to accept the terms of a separate agreement reached between Hermann von Salza, grand master of the Teutonic Order, and Gregory IX to restore the former Danish provinces to Denmark. In May 1237 Pope Gregory announced the incorporation of the Sword Brethren into the Teutonic Order in four letters to the relevant parties: the order, Hermann von Salza, William of Modena, and the bishops of Riga, Dorpat, and Ösel. Later in the summer the Teutonic Order in Marburg grudgingly accepted the unification, although this was only carried out in practical terms by the end of 1237, after the arrival of the first contingent of Teutonic Knights in Livonia.

Conclusions

Despite its short lifespan, it was the Order of the Sword Brethren that introduced the military religious order as an institution to the Baltic Crusades. Much more than the seasonal crusaders, it was able to fight and keep fighting according to a chosen strategy. Without its introduction, Christianity might not have survived in Livonia, and it was a sign of its initial success that it was taken as a model for the likewise short-lived Knights of Dobrin. Both orders, however, suffered from the lack of a European network of estates and houses outside their main region of activity that could provide them with financial resources and a secure basis of recruitment. In that sense it was logical that both were absorbed by the Teutonic Order.

Bibliography Benninghoven, Friedrich, Der Orden der Schwertbrüder (Köln: Böhlau, 1965).—, “Zur Rolle des Schwertbrüderordens und des Deutschen Ordens im Gefüge Alt-Livlands,” Zeitschrift für Ostforschung 41 (1992), 161-185. Ekdahl, Sven, “Die Rolle der Ritterorden bei der Christianisierung der Liven und Letten,” in Gli Inizi del Cristianesimo in Livonia-Lettonia: Atti del Colloquio internazionale di storia ecclesiastica in occasione dell’VIII centenario della Chiesa in Livonia (1186-1986), Roma, 24-25 giugno 1986, ed. Michele Maccarrone (Citta del Vaticano: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1989), pp. 203-243. Elm, Kaspar, “Die Ordines militares. Ein Ordenszötus zwischen Einheit und Vielfalt,” in The Crusades and the Military Orders: Expanding the Frontiers of Medieval Latin