By the aggressive enforcement of his feudal rights as overlord over the Scottish mainland, Alexander II had imposed the acceptance of the monarchy beyond the limits achieved by any of his predecessors. However, the lands in the northwest had continued to remain outside the perimeter of Scottish dominion and in 1230 the ruling council began to direct its initiatives toward securing the autonomous region. The western isles centered in the Hebrides had been under the marginal authority of the crown of Norway but, under the energetic and aggressive King Hakon IV, a new campaign had been mounted to reestablish Scandinavian sovereignty. The Norwegian offensive was focused on the Hebrides, successfully reasserting the power of Hakon IV as suzerain. To counter the growing influence of the Scandinavians over a region where the Scottish court had ambitions, Alexander II empowered the deposed Alan of Galloway to thwart the efforts of the Northmen. The lord of Galloway attacked and plundered the western isles, succeeding in limiting the effective- ness of the Norwegian subjugation incursion at little expense to the Canmore throne.

By 1242 the policies of Alexander II had secured his border with England and his active intervention in Arygll and the northern earldoms had effectively established Scottish supremacy over the magnates, clerics and population. However, the region to the northwest, centered on the Hebrides Islands, remained largely autonomous with feudal obligations to Norway and in 1244 the Scots began negotiations to acquire the Isles. The Norwegians had partially reasserted their overlordship in the Western Isles in 1230 but in recent years the local warlords had regained much of their authority. Envoys were dispatched to the Norwegian king, Hakon IV, offering to purchase the disputed area. The proposals were repeatedly rejected and, finding no peaceful resolution, Alexander II began to prepare for war. In Arygll several castles and burghs were fortified while their garrisons were strengthened to be used as a base of operations for the planned invasion. The royal council initiated a series of alliances with the nobles, assuring their loyalty and support against Hakon IV. As the Scots mobilized for war the Norwegians responded to the growing militancy by forging a counter-coalition with the powerful and ambitious warrior, Ewan Macdougall of Argyll, to strengthen his coastal defenses. In the spring of 1249 Alexander II assembled a formidable army and fleet, launching his naval expedition to conquer the Western Isles. Under the court’s battle plan the first objective was to eliminate the Macdougall faction in Argyll and impose its sovereignty over the rebellious area. With the major base of Hakon IV’s military power subdued with the seizure of Argyll, the naval force was to sail north, capturing the Hebrides. However, as his ships lay in anchor in Kerrera Sound, Alexander II became seriously ill with a fever, dying on July 8, 1249, before the campaign could be initiated. The ninth Canmore sovereign was nearly fifty-one and had ruled Scotland for thirty-five years. At his death he was succeeded by his seven-year-old son, Alexander III.

Scotland under Alexander III experienced its first golden era, characterized by a growing prosperity, stable and responsive government and an expanding international presence. Alexander III’s first two years of kingship had resulted in an accommodation with his magnates, ending the years of political strife, and had reestablished amiable relations with England, which enabled Scotland to pursue an aggressive foreign policy in the north.

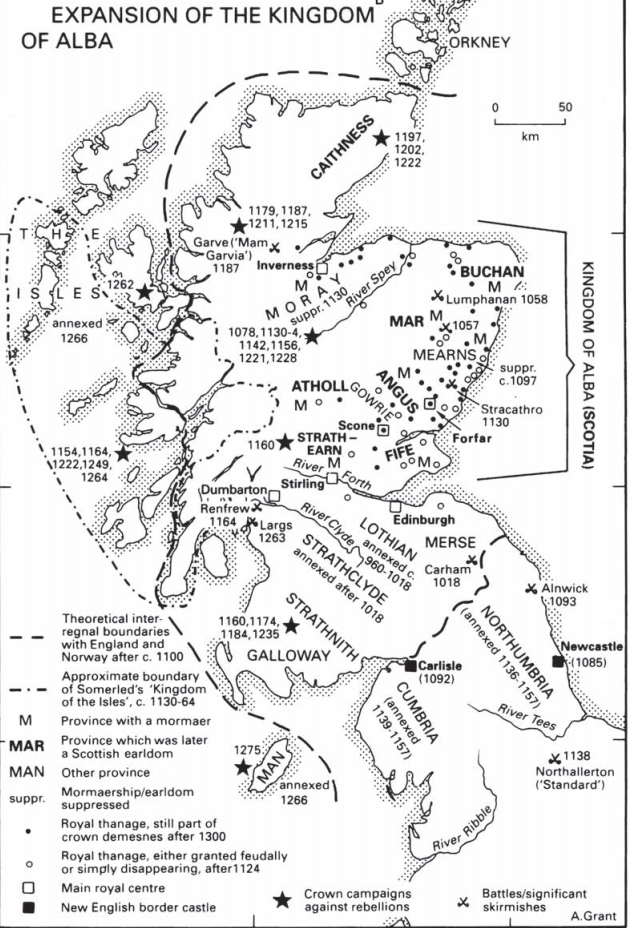

The Scottish kings had steadily advanced their sovereignty into the Highlands and had begun to contend for control of the Western Isles as early as the late eleventh century during the reign of Edgar I. The maritime fiefdoms consisted of a chain of islands and the northern- most coastline of the Sea of the Hebrides and formed a part of the seaborne empire of Nor- way. In 1261 Alexander III revived his father’s plan for northern expansion, dispatching envoys to the Scandinavian court of Hakon IV in an attempt to purchase the Isles. While the ongoing negotiations evolved the Scottish regime began to make arrangements for war by buttressing its defenses along the maritime coast. The royal castles were strengthened and the garrisons reinforced with additional troops. As Alexander III traveled through the kingdom to rally the warlords to his cause, he ordered the regional earls to mobilize their local military forces while war provisions were stockpiled and a small number of mercenary soldiers hired.

In the spring of 1262 the Scottish negotiators returned home with Hakin IV’s formal rejection of the proposed fiefdom purchase. As relations between the two realms deteriorated, Alexander III renewed his claims to the Isles, ordering the earl of Ross to mount a pillaging raid against the Norwegian-held island of Skye. With hostilities intensifying the Norwegian court began to assemble its navy and military forces, preparing to depart for the Western Isles to defend its demesne. In July the Norse squadron of over forty vessels sailed for the Shetlands and down the Scottish coast where they were joined by ships from their allies in the Isles and the Isle of Man, which swelled the fleet to over two hundred. In September Hakon IV sent emissaries to Alexander III with an offer of peace if the Scots would agree to respect Norwegian sovereignty over the Western Isles. The negotiations dragged on into late September while the Highlanders rallied to Alexander III in defense of their kingdom against a foreign incursion. While the Canmore throne massed its militia, the Norse navy was anchored off Largs in the Firth of Clyde on September 30, where during the night a strong gale blew many of the ships against the shore. In the morning the Norwegian king personally led a landing party of over one thousand soldiers ashore to rescue the stranded troops when the Scots mounted their attack. The Norsemen were steadily driven back while Hakon IV managed to escape with a small band of his army. The combined losses from the battle and storm compelled the Norwegians to abandon their invasion campaign, sailing north to Orkney. Due to the lateness of the season, with the increased risk of severe storms, Hakon IV was forced to spend the winter on the island. With much of the Norse fleet still intact, Scotland continued to face the danger of an encroachment but the balance of power shifted in Alexander III’s favor in December when Hakin IV died.

The Scandinavian navy remained a serious threat to Scotland, but the new king, Mag- nus VI, was beset with unrest in his realm, sending envoys to Alexander III to mediate a settlement. Delaying the talks the Scots seized the initiative by invading the Hebrides, occupying much of the Norse fiefdom. When negotiations began anew in 1265 Magnus VI had lost the military advantage and was forced to agree to the harsh terms of the Treaty of Perth dictated by Alexander III. Under the accord the Inner and Outer Hebrides were annexed to Scotland along with the Isle of Man for a cash payment. While the battle of Largs had been inconclusive, its aftermath was decisive for the Scottish kingdom, securing the regime’s power base in the northwestern territories.

ARMIES OF SCOTLAND

The largest part of any Scottish force during this era was provided by me ‘common army’ or exeriticus Scoticanus (me ‘Scottish army’), composed mainly of poorly equipped farmers and neyfs (or nativi, actually called by the Scandinavian term bondi in Caithness, Fife and Stirlingshire, heavily-settled by Norsemen during the Viking era and, in the case of Caithness, still pan of Norway until the 13m century). The neyfs were- or, rather, became during this period – unfree men (but not slaves) tied to the land where they had been born, who could be sold or given away with the land. Such military service as they owed, referred to variously as common, Scottish or forinsec service, was assessed by me ploughshare or on me davach, carucate arachor or (all of which were units of arable land), the number of men required varying but most commonly involving one man per unit, though in exceptional circumstances (such as a proposed expedition into England in 1264 in support of Henry III against Simon de Montfort) up to 3 men could be demanded. On occasion such military service could even involve every able-bodied freeman of 16-60 years; certainly in Robert the Bruce’s wars it was required of every man ‘owning a cow’. At shire level the ‘common army’ was led by local, non-feudal officials called thanes (often displaced by feudal barons in the 13th-14th centuries), the muster of a whole earldom being led by its earl or, north of me Tweed, its mornaer-(King David I, 1124-53, began the transformation of the latter, hereditary Gaelic chieftains, into feudal earls). Such contingents constituted the bulk of the Scottish forces at Northallerton (1138), Largs(1263), Stirling Bridge (1297), Falkirk (1298) and most other large-scale engagements. By the 13th century Scottish service can sometimes be found being convened to a feudal obligation.

A small number of Norman knights had been introduced into the Scottish court as early as 1052-54, in the reign of Macbeth (1040-57), and there was even an attempt to introduce Anglo-Norman feudalism under Duncan II before the end of the 11th century, though this and the employment of further Anglo-Norman knights resulted in a rebellion against him. Feudalism was only successfully introduced on a widespread basis in southern Scotland by David I and in northern Scotland by his successors Malcolm IV (1153-65) and William the Lion (1165-1214), but it never became established in me Highlands and me far north. King David had spent much of his youth at the court of Henry I of England and when he succeeded to the throne a large number of Anglo-Norman knights accompanied him to Scotland, soon coming to hold most of the highest offices in the royal household; indeed, English mercenary knights remained apparent in the Icing’s household throughout the late-11th and 12th centuries. Even in the half-century of William the Lion’s reign, evidence exists for only 37 enfeoffments, of which one was for 20 knights, two were for 10 knights, one for4 knights, two for 2 knights, one for 11h knights and 18 for the service of a single knight each, the remaining 12 all being for fractions (a half-fief being the most common). From the evidence of 13th century enfeoffments it is apparent that even in the 12th century holdings of a half or quarter-fief usually owed the service of a sergeant, or an archer, in a light mail corselet (a haubergel), usually mounted but sometimes serving on foot. In part at least these probably represent the ‘common army’ feudalised. Feudal military service was due for the usual 40-day period, but there are also many references to 20 days. Principal military officers in Scotland’s feudal hierarchy were the Steward (which post gave its name to its hereditary holders, the Stuarts), Constable and Marischal.

Church lands seem to have been liable only for ‘common army’ service, not for knight service, and even this could be satisfied under certain circumstances by payments in kind. Scutage itself does not seem to have been levied in Scotland until the 13th century.