Lawrence had already decided to pull out when the Arab lookout on top of the hill shouted down that a train was standing at Hallat Ammar Station. By the time he had climbed up to look for himself, the train was moving. Racing back down the slope, he yelled to his men to get into position, and there was a wild scramble over sand and rock.

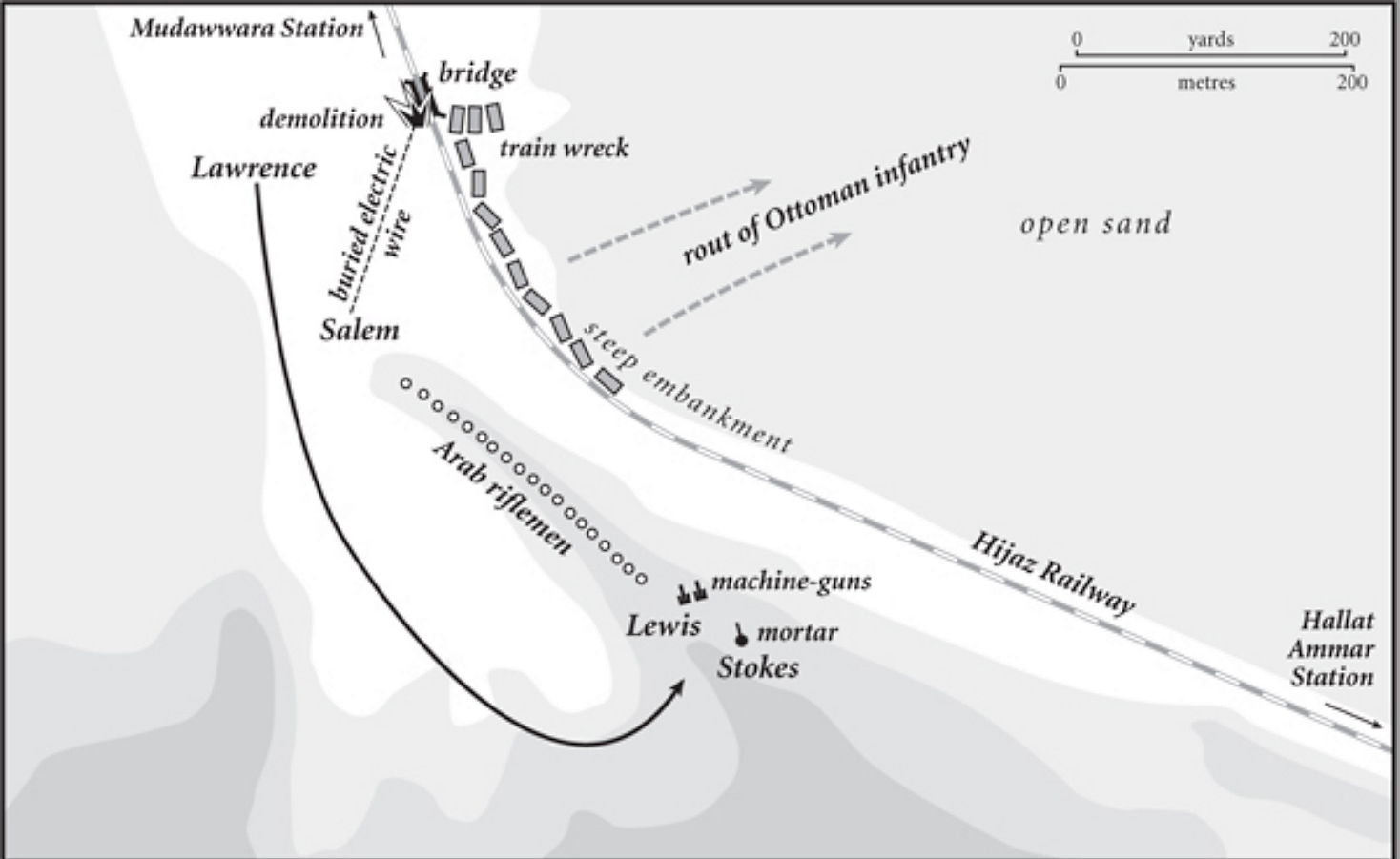

The 80-odd riflemen were posted in a line just below the lip of a low ridge running parallel with the railway and about 150 yards from it. Two sergeant-instructors had set up their weapons at one end of this line, about 300 yards from the intended demolition, and so placed that they would take the train in enfilade. Yells, an Australian, ‘long, thin, and sinuous, his suppled body lounging in unmilitary curves’, had charge of two Lewis light machine-guns, and Brooke, ‘a stocky English yeoman, workmanlike and silent’, operated a Stokes mortar; accordingly they were known as ‘Lewis’ and ‘Stokes’. Salem, Feisal’s best slave and one of four with the expedition, having pleaded for the honour of operating the exploder, was waiting in some hollows at the bottom of the ridge. Lawrence had spent some hours the previous day planting a 50lb charge of blasting gelatine on top of a bridge and then burying the 200-yard cable. He now placed himself on a little hillock near the bridge from which he could signal to Salem when the moment for detonation came.

One man continued to keep watch from the hilltop: a necessary precaution, for if the train were to halt and the troops it carried disembark behind the hill, the raiders would be taken in the rear. But it kept coming, making as much speed as it could. The Ottomans aboard, already alerted to the presence of a raiding party in the area, opened a random fire into the desert. The racket of steam engine and shooting sounded steadily louder as the train approached the waiting men. Salem ‘danced round the exploder on his knees, crying with excitement, and calling urgently on God to make him fruitful’. But Lawrence became anxious. There was a lot of firing from the train. How many men was this? Were there enough Arabs to deal with them? The fight would be at close-quarters, and escape hazardous if things went wrong.

Much had already gone wrong. Lawrence had set out from Aqaba on 7 September intending to attack Mudawwara, an oasis settlement with a substantial water-supply about 100 miles south of Maan. Disruption of the water installations here would have imposed a heavy logistical burden on the Ottomans, forcing them to fill trains with water, both to service the railway and supply their garrisons. But bickering between rival clans of Howeitat at Guweira had prevented him raising the 300 men he needed, and he had returned to Aqaba to seek Feisal’s assistance. Setting out again a week later, he had barely a third of the number he wanted: about 100 tribesmen, 4 slaves and 10 freedmen of Feisal’s, and the 2 British Army weapon specialists. Nor had the tribal tensions been resolved. The most senior Arab leader present was Zaal abu Tayi, Auda’s nephew, but only 25 were his clansmen, and the rest questioned his authority, so Lawrence found himself de facto leader of an expedition that was ‘not a happy family’. They headed east, nonetheless, through the mountains of Rum, with their towering red-sandstone cliffs and black-basalt screes, then out across the baked mud-flats beyond and through the sand desert, reaching Mudawwara, 50 miles distant, late on the second day (17 September). But the position was too strong to attack: reconnaissance revealed a long line of station buildings transformed into blockhouses, and a garrison estimated at 200 to 300 strong.

After camping for the night, the raiders headed south, towards a range of low hills, seeking a place for an ambush. Having selected a site and laid a charge, they began the long wait for a train. Before one came, however, the Arabs detailed to guard the camels climbed to the top of the ridge and were seen silhouetted against the skyline both from Mudawwara Station, about 9 miles to the north, and Hallat Ammar Station, 4 miles to the south. It was already sunset, too late for the Turks to react to what they had seen. But early next day, a detachment of about forty set out from Hallat Ammar. Some thirty Bedouin were dispatched to distract them. Around noon, matters became critical when a further 100 Turks headed out from Mudawwara. The raiding party was in danger of having its line of retreat cut off. Precipitate withdrawal was delayed only by the last-minute sighting of the train at Hallat Ammar, steam up, about to move.

The ambush site had been well-chosen. The main hill provided a vantage-point for observation and concealed the presence of the raiding party. The railway turned a double dog-leg at this point, running east–west for a short distance, parallel with the 50ft high ledge of rock where the Arab riflemen were posted on the morning of 19 September. Just beyond the second dog-leg, as the line resumed its northward progress, it passed over a low, two-arched bridge. This was ideal for a demolition. The locomotive was likely to plunge into the wadi, pulling the carriages behind with it; and even if the locomotive somehow got clear, the carriages would be derailed by the broken arch and their own forward momentum.

But Lawrence’s anxiety increased when the train ‘rocked with screaming whistles into view around the bend’. Instead of one engine, there were two, and these were followed by ten box-wagons, rifle-muzzles at every door and window, and little sandbag emplacements of Ottoman soldiers on the roofs. He made the snap decision to detonate the charge under the second locomotive, ‘so that however little the mine’s effect, the uninjured engine should not be able to uncouple and drag the carriages away’.

The two locomotives steamed past the rocky ledge which concealed Lewis guns, Stokes mortar, the over-excited Salem with his exploder and eighty Arab riflemen. When the driver of the second engine was over the bridge, Lawrence raised his hand. ‘There followed a terrific roar, and the line vanished from sight behind a spouting column of black dust and smoke 100 feet high and wide. Out of the darkness came shattering crashes and long, loud metallic clangings of ripped steel, with many lumps of iron and plate; while one entire wheel of a locomotive whirled up suddenly black out of the cloud against the sky, and sailed musically over our heads to fall slowly and heavily into the desert behind. Except for the flight of these, there succeeded a deathly silence, with no cry of men or rifle-shot, as the now-grey mist of the explosion drifted from the line towards us, and over our ridge until it was lost in the hills.’

The bridge was destroyed by the blast. The front engine was derailed and left listing, its cab burst, steam hissing at pressure. The cab and tender of the second engine were torn to strips and cast amid the rubble of the bridge, ‘a blanched pile of smoking iron’. The front wagon had plunged into the mini wadi. Filled with typhus victims, ‘the smash had killed all but three or four, and had rolled dead and dying into a bleeding heap against the splintered end’. The succeeding wagons were derailed and damaged, some with buckled frames. Parts of cylinders, wheels, pistons and boiler-plating had been hurled up to 300 yards from the centre of the blast. The effects of the explosion had exceeded expectations.

In the momentary lull, as the protagonists – dazed Turks in the broken wagons, awestruck Arabs on the ledge above – came to their senses, Lawrence raced to join the British NCOs. As he did so, the Arabs surged forward to within 20 yards or so of the wrecked train. The little desert battlefield was soon alive with lethal close-range fire, the bullets ripping into the woodwork of the slumped carriages as soldiers tumbled from the doors. Then the machine-guns opened up. Though disadvantaged by their height – resulting in plunging rather than sweeping fire – the Lewis guns were angled along the enemy line, ‘and the long rows of Turks on the carriage roofs rolled over, and were swept off the top like bales of cotton before the furious shower of bullets which stormed along the roofs and splashed clouds of yellow chips from the planking’. The Turks who managed to get clear scurried behind the railway embankment, which sloped steeply on the far side, and there improvised a firing line, shooting back through the wheels at the Bedouin opposite.

A protracted firefight might have ensued, but this the Arabs could not afford with columns approaching from north and south: they needed a quick end. ‘The enemy in the crescent of the curving line were secure from the machine-guns. But Stokes slipped in his first shell, and after a few seconds there came a crash as it burst beyond the train in the desert. He touched the elevating screw, and his second shot fell just by the trucks in the deep hollow below the bridge where the Turks were taking refuge. It made a shambles of the place. The survivors of the group broke out in a panic across the desert, throwing away their rifles and equipment as they ran. This was the opportunity of the Lewis gunners. The sergeant grimly traversed with drum after drum, till the open sand was littered with bodies.’

It had taken 10 minutes. The fighting had been sudden, bloody and one-sided. Seventy Turks had been slain, most killed by the Stokes mortar or the Lewis machine-guns, with another thirty wounded and ninety taken prisoner. Only two Arabs had been killed and three wounded.

The moment it ended, the Arabs rushed the train and tore it part. The scene was transformed from one of close-quarters killing to one of frenzied plundering.

The valley was a weird sight. The Arabs, gone raving mad, were rushing about at top speed bareheaded and half-naked, screaming, shooting into the air, clawing one another nail and fist, while they burst open trucks and staggered back and forward with immense bales, which they ripped by the rail-side, and tossed through, smashing what they did not want. There were scores of carpets spread about; dozens of mattresses and flowered quilts; blankets in heaps; clothes for men and women in full variety; clocks, cooking-pots, food, ornaments and weapons … Camels had become common property. Each man frantically loaded the nearest with what it could carry and shooed it westward into the void, while he turned to his next fancy.

The withdrawal was chaotic but successful. The Bedouin fled westwards across the desert with their booty as soon as they could, the war band now transformed into ‘a stumbling baggage-caravan’. Lawrence and the two NCOs remained behind to bring off the electrical cable and the guns. They were assisted by Zaal and his cousin, who rushed back with some camels in the nick of time. The train-wreck and the dead were then left to the little columns of Turks trudging towards the battlefield from Mudawwara and Hallat Ammar Stations.