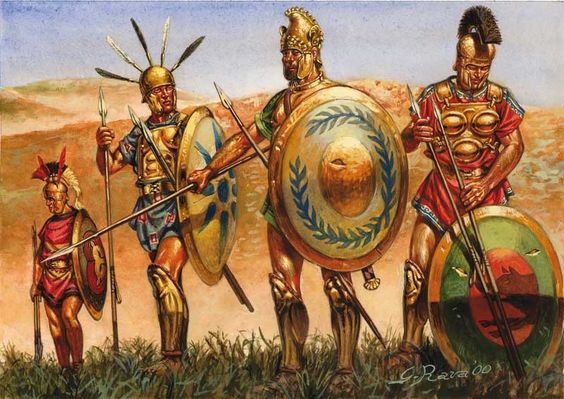

South Italic warriors, c. 400BCE, art by Giuseppe Rava

A spear sacred to Mars was laid upon the ground and Mus stood upon it. Denter helped the consul recite the terrible prayer of devotio, the same with which the original Decius Mus had devoted himself at Battle of the Veseris. It is possible that Livy or his sources invented this, but it seems likely that it derives from pontifical or other priestly records of religious formulae:

Janus, Jupiter, Father Mars, Quirinus, Bellona, Lares, divine Novensiles, divine Indigites, you gods in whose power are both we and the enemy, and you, divine Manes, I invoke and worship you, I beg and crave your favour, that you prosper the might and victory of the Roman people and visit on their enemies fear, shuddering and death. As I have pronounced these words on behalf of the Republic of the Roman people, and of the army and the legions and auxiliaries . . . I devote the legions and auxiliaries of the enemy, along with myself, to the divine Manes and Tellus.

The younger Mus added some grim imprecations to this vow of death:

I will drive before me fear and panic, blood and carnage. The wrath of the heavenly gods and the infernal gods will curse the standards, weapons and armour of the enemy, and in the same place as I die witness the destruction of the Gauls and Samnites!

Denter helped Mus don the ritualistic garb of the devotus. This was the cinctus Gabinius, a toga hitched in such a way that a man could ride a horse and wield a weapon. The consul was ready to meet his destiny, but first proclaimed Denter propraetor (he had been consul in 302 BC). Thus invested with imperium, Denter assumed command of the consular army.

Brandishing the spear of Mars, Mus spurred his way through the broken antesignani, charged into the ranks of the advancing Senones and impaled himself on their weapons. The death of a general, the focus of command and authority and leadership, usually triggered the collapse of an army, but the news of Mus’ glorious demise, transmitted by Denter, rallied the hard-pressed Roman infantry and they turned on their opponents with renewed vigour. According to Livy, Mus’ heroic death had the effect of instantly paralyzing the seemingly victorious Gauls:

From that moment the battle seemed scarce to depend on human efforts. The Romans, after losing a general – an occurrence that is wont to inspire terror – fled no longer, but sought to redeem the field. The Gauls, especially those in the press around the body of the consul, as though deprived of reason, were darting their javelins at random and without effect, while some were in a daze, and could neither fight nor run away.

The Senones’ reaction seems entirely fantastic but is it entirely fictitious? Is it merely the over-egged reconstruction of a patriotic Roman historian or does it have some basis in reality? Livy was keen to describe how the self-sacrifice of Mus brought on the aid of Tellus and Manes and the form that aid took, but were the Senones aware they had killed a devotus? It is possible that they did, and their reaction, although exaggerated, was one of shock and caused their advance to halt.

It was suggested above that the Picentes chose alliance with Rome rather than with the Samnite-led coalition because of their hatred of the Senones. The Senones had encroached on the lands of the proud Picentes for more than a century. The Picentes famously took their name from the sacred picus of Mamers that had led them to the east of the Appenines. The association with Mamers/Mars is underlined by considerable archaeological finds of arms and armour that demonstrate the martial nature of ancient Picenum. They were talented smiths, developing elaborate ‘pot’ helmets and the original Negau-type which were adopted throughout Italy in the sixth and fifth centuries BC and employed by Italic mercenaries serving abroad, for example in Sicily. The ‘Woodpeckers’ did lose a portion of their northern territory to the Senones, but their success in halting the Gallic advance and holding the remaining country testifies to their military prowess. There is also evidence to suggest that the Picentes knew of the ritual of devotio and employed it in battle.

In an excursus about devotio following his account of the Veseris, Livy notes that a Roman commander could nominate an ordinary legionary to take his place and die among the enemy. This substitution would eliminate the possibility of the Roman army panicking at the death of its commander, and volunteers were probably not difficult to find. The honour falling on the family of a successful devotus would be immense. The use of substitutes should lead us to suspect that devotiones were more common occurrences than the sources suggest, but only the successful devotiones of great men entered the written record.

Devotio or devotio-like practices were not unique to the Romans and Latins, and if the enemy realized that a devotus was seeking death, every effort would be made to capture the man alive (cf. the orders of Pyrrhus at Ausculum, below). If the devotus, whether a general or a common soldier, failed to die, an expiatory offering had to be made to the gods cheated of the promised sacrifice of the devotus and the enemy soldiers. A 7 feet tall statue of the failed devotus was buried in the ground and a victim sacrificed over it. Likewise, if the devotus was unsuccessful and lost to the enemy the spear sacred to Mars, a pig, sheep or an ox was sacrificed to placate the god.

In 1934 the limestone statue of an Italic warrior was discovered buried in a vineyard near Capestrano. It had not toppled to the ground and gradually been covered over with soil, but was deliberately buried, like a body in a grave. The back of the statue remained in perfect condition, suggesting that it was buried immediately after its production, around 500 BC. The statue is 7 feet tall. The figure wears typical central Italian body armour, the details of which are emphasized with paint: a bronze gorget and disc cuirass, a broad bronze belt and an apron to protect his vulnerable abdomen. His arms are crossed over his chest and he clutches a short sword and a small axe, while javelins with throwing thongs are carved on the vertical supports that hold up the figure. Capestrano is located in what was the territory of the Vestini, but the warrior wears a broad-brimmed Picene helmet with a great crest and the inscription on the statue, not yet deciphered, is in a southern Picene dialect. It has been suggested that the Capestrano Warrior represents a very high status – his rich panoply was far beyond the means of a common soldier – but failed devotus.

If the Capestrano Warrior does represent a devotus, it would demonstrate that the Picentes employed devotio. We can postulate that a Picene devotio was essentially similar to a Roman devotio: the king, general or lower-ranking substitute invoking the gods, vowing to sacrifice himself and the forces of the enemy, followed by the donning of ritual costume or armour and the lone charge to the death. The opponents against whom the Picentes were most likely to employ this ritual tactic were the Senonian Gauls.

If the Senones were familiar with devotio or similar practices from warfare against the Picentes and other Italian peoples, the warriors at Sentinum would have recognized the features of devotio in Mus’ suicidal charge. The realization that they had unwittingly carried out a sacrifice that would set the gods against them could well have caused their advance to falter. The impact of the divine on ancient Italian warfare should not be underestimated. This was an intensely religious and superstitious age, and even if the Senones were unsure about which gods were being called on to aid the Romans (by this time the Gauls had probably adopted a considerable number of native Italian deities), they recognized ritual practice, knew the powers and whims of the gods and they would have known fear and panic.

That Mus’ antesignani rallied on witnessing his death demonstrates they had been forewarned that their general might devote himself and, if so, not to panic but rejoice, for the enemy would be doomed. The situation was reversed: Romans turned to pursue Senones, but the Gallic warriors had recovered some of their composure and did not flee pell-mell as the Roman cavalry had. They halted and organized themselves into a strong testudo formation. Like the Romans, the Gauls protected themselves with tall shields, well-suited to form the walls and roof of the testudo (‘tortoise’). The testudo is famous from later Roman warfare. If it remained unbroken, it provided excellent protection against missiles and cavalry. Marc Antony’s extraordinary retreat from Parthia in 36 BC was facilitated by use of the marching testudo. The chieftains of the Senones were experienced enough as commanders to realize the dangers of flight from battle – most casualties occurred during the pursuit of broken troops by cavalry. If they could last out the day in the testudo, they should be able to retreat safely under the cover of night. Of course, they may still have hoped for victory. The Samnites continued to fight on the left and if Rullianus was defeated, they would come to the relief of their Gallic allies.

The battle on the Roman right went as Rullianus had predicted. Gellius Egnatius launched his warriors in furious charges at the hastati, but the Romans and allies held firm. The classic Roman infantry formation, that is, the three ordines of maniples (triplex acies), was designed for mobility and attack, the maniples separated by considerable intervals and acting like miniature attack columns. However, one wonders how suitable this open battle formation was to Rullianus’ defensive, and presumably static, tactics.

The intervals between the maniples of ‘heavy’ infantry (not really an appropriate description but nonetheless useful) were protected by bands of ‘light’ troops called rorarii. Known by the end of the third century BC as velites (‘swift ones’), these were the poorest and usually youngest troops. There were even poorer Roman and Latin citizens, proletarii, who were generally exempt from military service, but the rorarii had at least the means to afford a bundle of light javelins, a sword, shield and helmet. They could not afford body armour. The rorarii fought in swarms, they were not led by centurions and signiferi (standard-bearers), but relied on their own initiative. Before the main battle lines enagaged, they would skirmish in front of the army, using hit-and-run tactics to thin the leading ranks of the enemy or to provoke him into a rash and disorderly attack. The later velites, and perhaps the earlier rorarii as well, wore wolf skins over their helmets to make them conspicuous to senior officers who would take note of acts of valour. Having considerable freedom of movement, these light troops were encouraged to engage in single combat and were eligible for particular military awards (dona militaria). When the main battle lines came up, the rorarii would retreat to the intervals between the maniples: any enemies advancing into the tempting gap would be stung by their light javelins. It is conceivable that attackers also risked being caught in a ‘crossfire’ of pila from the legionaries in the outside files of the maniples to either side, and that the maniple in the following line, positioned to cover the gap, would charge forward. Samnites were notable for the speed of their charges. Lightly equipped – most Samnite warriors were protected by only a scutum (a shield) a helmet, and armed with a couple of dual-purpose thrusting and throwing spears or pila – they could rush the intervals and force their way into the flanks and rears of the maniples. Rullianus, who knew too well the devastating effect of the swift Samnite onslaught from Lautulae, may have arranged his maniples of hastati without the usual intervals, allowing them to form a continuous wall of shields on which the Samnites could exhaust their missiles, energy and resolve.

The hastati would not break and at length the war cries, javelin volleys and charges of Gellius Egnatius’ warriors waned. Rullianus judged the time was ripe to attack. He ordered the prefects commanding the cavalry turmae to work their way forward and be ready to attack the left flank of Egnatius’ army. This suggests that whatever cavalry the Samnite general had was sufficiently weakened or had already retired from the action. The consul then gave the order for the infantry to advance, but this was not yet an all-out charge, only a probe; he was still wary and needed to confirm that the enemy were indeed exhausted. The Samnite maniples were pushed back easily. Rullianus called up reserves he had deliberately held back for this moment. It is uncertain if these were combined legionary and allied principes and/or triarii, or just allied cohorts, nor is it made clear where he positioned them, but in combination with the legionaries they delivered the hammer blow that caused Egnatius’ army to break. Rullianus gave the signal, by trumpet, and the infantry drove forward. Simultaneously the Roman cavalry charged at the Samnites’ left flank. The physically exhausted and demoralized Samnites cracked and they fled back to the confederate camp, easy prey for the swift Roman cavalry. The flight of the Samnites meant that the Senones, still holding out in their testudo, were completely exposed and the Romans hastened to encircle them.

Meanwhile, Livius Denter was busy riding along the ranks of Mus’ army shouting out that the consul had devoted himself, thus making victory certain:

The Gauls and the Samnites, he said, were made over to Tellus and to the Manes. Decius was haling after him with their devoted host and calling it to join him, and with the enemy all was madness and despair.

The arrival of Scipio Barbatus and Marcius Rutilus with reinforcements from Rullianus’ ‘rearmost battle line’, presumably triarii, also helped to rally Mus’ army. On learning of Mus’ sacrifice the former consuls resolved to ‘dare all for the republic’ and destroy the Senones’ testudo. Orders were given to collect up all the pila, javelins and spears littering the battlefield, and to bombard the enemy. Initially, the volleys of missiles had little effect, but gradually javelins found their way through small gaps in the wall and roof of shields. Injured warriors dropped their shields and the front of the testudo was gradually opened up.

Rullianus, now aware of Mus’ death, broke off his pursuit of Egnatius’ men and crossed the river to attack the Gallic tortoise. He sent 500 of his picked Campanian horsemen, followed by the principes of the Third Legion, to circle around the testudo and to make a surprise assault on its rear. ‘Make havoc of them in their panic,’ he told his men. The unexpected charge of the Campanian turmae succeeded in opening gaps in the enemy formation. The 1,200 principes forced their way through the openings and split the tortoise apart. Rullianus then returned to the pursuit of Egnatius. Such was the crush at the gates of the camp that many warriors were unable to enter. Gellius Egnatius rallied these men and formed a battle line to meet Rullianus.

On approaching the camp the consul called on the great god Jupiter, in his guise as the Victor. Victory was now certain, but the Roman general knew how dangerous Egnatius and his men would be as they made their last stand. We may also assume that it was late in the day and Rullianus feared that a considerable portion of the enemy would escape under the cover of night, so he vowed to the god a temple and the spoils of battle in return for a complete victory. It seemed to the Romans that Jupiter heard Rullianus, for Egnatius was cut down and his men were quickly swept aside. The Romans and allies then surrounded the enemy camp. The Senones, assailed from front and rear, were annihilated. The Battle of the Nations was over.

The Samnites and Senones lost 25,000 men that day – less than Livy’s favourite and exaggerated casualty figure of 30,000 and therefore probably reasonably accurate. Another 8,000 were taken captive, probably mostly those Samnites who had made it into the apparent safety of the camp. At least 5,000 Samnites did escape, but as they headed for home via the territory of the Paeligni, they were attacked. The Paeligni, now of course allies of Rome, killed 1,000 of the Samnite fugitives. Some Gallic infantry might have made good their escape from Sentinum, but most of the warriors in the testudo must have been either killed or enslaved – supposing that they were given the opportunity to surrender. It is uncertain what happened to the Senonian cavalry and chariots. Did the former rally when Mus’ squadrons were panicked by the unexpected attack of the charioteers, or did they continue their flight? Likewise, what happened to the charioteers? Some presumably continued the pursuit of the broken Roman cavalry, but did those that forced their way into the infantry retire before the Romans rallied?

As we have seen, Livy was usually reticent about listing Roman casualties but for Sentinum he made an exception. This was, after all, the greatest battle yet fought by Rome and her losses served to underline the scale and importance of the struggle. Rullianus’ casualties were relatively light, 1,700 killed, but Mus’ army was severely mauled with 7,000 killed. Sentinum was no easy victory and it was not even the decisive battle of the Third Samnite War. The Samnites would continue the struggle for five more years, and the Etruscans and other peoples remained troublesome, but never again would Rome be faced with such a dangerous coalition of Italian peoples. It also served to bring Rome to the notice of the wider Mediterranean world. The city-states and kingdoms of the Greek East, focussed on the titanic struggles of the Successors of Alexander the Great had, with the exceptions of Magna Graecia and Carthage, paid little attention to events in the West, but now they took note of the new and powerful player on the scene.

Rullianus sent soldiers to search for the body of Decius Mus, but it was not found until the following day. Like his father at the Veseris, Mus was finally discovered under a heap of enemy dead. His corpse was carried to the Roman camp and there was great lamentation. Rullianus immediately oversaw the funeral of his colleague, ‘with every show of honour and well-deserved eulogisms,’ says Livy. Zonaras, whose account derives from Dio, adds that Mus was cremated but this seems to be based on the assumption that the consul’s body was burned with the spoils. In fulfilment of his vow Rullianus had the spoils gathered from the enemy, piled up and burned in offering to Jupiter the Victor. However, only a proportion was given over to the god; the rest was reserved for his legionaries. Rullinaus would have carried Mus’ remains back to Rome to be handed over to the Decii for deposit in the family tomb, but it has been suggested that a grave discovered under the altar of the temple of Victoria in Rome belongs to Mus, and that he was honoured with burial there when Postumius Megellus dedicated the temple in 294 BC. The year in which Rullianus dedicated his temple to Jupiter the Victor is not known, but the day and month on which the event occurred is recorded: 13 April, perhaps the anniversary of the day on which the vow was made.

Triumphatores

Rullianus crossed back over the Apennines, leaving Decius Mus’ army to keep watch in Etruria (we do not know whom he left in command), and returned to Rome with his legions. On 4 September he celebrated a triumph over Samnites, Gauls and Etruscans. The inclusion of the latter people may be an error. Following his triumph Rullianus was recalled to Etruria to put down the rebellion of Perusia and later historians may have coupled this victory together with the Sentinum campaign. Another explantion is that Rullianus did triumph over Etruscans as well as Gauls and Samnites because he was able to take the credit for Fulvius Centumalus’ victory over the Perusini and Clusini. Centumalus was, after all, following Rullianus’ orders and fighting under his auspices. The triumphing legionaries were each rewarded eighty-two bronze asses (either ingots or rudimentary coins) and a tunic and sagum (military cloak) from the spoils not dedicated to Jupiter the Victor. The garments would have been those stripped from the enemy and we can imagine that the finely-made, colourful and embroidered garments of Senone and Samnite nobles were highly prized.

While Rullianus and Mus were campaigning in Etruria and Umbria, Volumnius Flamma was operating in Samnium. Livy reports that the proconsul drove a Samnite army up Mount Tifernus and, despite the difficulties of the terrain he defeated this army and caused its troops to scatter. The circumstances of this victory are uncertain. Did the proconsul defeat a Samnite force that was about to invade Campania, or did he invade Samnium in order to prevent reinforcements from being sent to Gellius Egnatius? Late in the year, seemingly after Rullianus’ triumph, Samnite legions attacked the territory of Aesernia in the upper valley of the Volturnus, while others marched down the Liris, simply ignored the new small citizen colony at Minturnae and ravaged the country around Formiae and Vescia. Aesernia was located a little to the north of Mount Tifernus, but we do not know when the Romans captured it. The strategically positioned stronghold probably changed hands many times, and Volumnius Flamma may have captured it following his recent victory on Mount Tifernus. By this time the Decian army, as the survivors of Decius Mus’ force were known, had left Etruria and returned to Rome probably to be formally disbanded. The withdrawal of the army encouraged Perusia to take up arms, but Rullianus hastened to the north (with his Sentinum legions?) and inflicted a sound defeat on the Etruscans. Livy reports 4,500 of the enemy killed and, most interestingly, that the 1,740 taken captive were not sold as slaves but ransomed back to their families and clans for 310 asses each. This was presumably conceived of as a swifter way to make a profit from the spoils and perhaps also to deliberately empty the coffers of Perusia and hamper the city’s future war efforts.

The praetor Appius Claudius assumed command of the Decian army and marched south along the road he had built to drive the Samnite raiders from the Auruncan country. The Samnites withdrew before him and combined forces with their comrades who had advanced down the Volturnus from Aesernia to Caiatia. Flamma, probably based around Capua, joined his legions with those of Appius at Caiatia and together they defeated the Samnites. It was a typically bitter engagement but Livy’s casualty figures may be exaggerated – 16,300 Samnites killed and 2,700 taken captive. The number of Roman dead also amounted to 2,700. Appius lost a few more men during the course of the campaign but not to enemy action; these unfortunates were struck by lightning.

Livy ends his account of the year 295 BC with a stirring tribute, but not to the devotus Mus or the triumphator Rullianus; Livy praises the courage and tenacity of the Samnites, the greatest of Rome’s opponents:

The Samnite wars are still with us, those wars which I have been occupied with through these last four books, and which have gone on continuously for 46 years, in fact ever since the consuls, Marcus Valerius [Corvus] and Aulus Cornelius [Cossus Arvina], carried the arms of Rome for the first time into Samnium. It is unnecessary now to recount the numberless defeats which overtook both nations, and the toils which they endured through all those years, and yet these things were powerless to break down the resolution or crush the spirit of that people; I will only allude to the events of the past year. During that period the Samnites, fighting sometimes alone, sometimes in conjunction with other nations, had been defeated by Roman armies under Roman generals on four several occasions, at Sentinum, amongst the Paeligni, at Tifernum, and in the Stellate plains [= Caiatia]; they had lost the most brilliant general they ever possessed; they now saw their allies – Etruscans, Umbrians, Gauls – overtaken by the same fortune that they had suffered; they were unable any longer to stand either in their own strength or in that afforded by foreign arms. And yet they would not abstain from war; so far were they from being weary of defending their liberty, even though unsuccessfully, that they would rather be worsted than give up trying for victory. What sort of a man must he be who would find the long story of those wars tedious, though he is only narrating or reading it, when they failed to wear out those who were actually engaged in them?

The Samnites had suffered painful defeats but as Livy emphasizes, they would not give up the fight. Rumours reached Rome that the Samnites had levied three new armies: one to continue the work of Gellius Egnatius and link up with allies in Etruria, another to devastate Campania, while the last would guard Samnium. The rumours were only partly correct. Rather than return to Etruria, early in 294 BC the Samnites seized part of the Marsian territory and installed a powerful garrison in Milionia. This stronghold, the precise location of which is unknown, probably straddled part of the Romans’ usual route to the Adriatic coast. The consuls of 294 BC, Postumius Megellus and Marcus Atilius Regulus (probably the son of the consul of 335 BC), were both assigned Samnium as their ‘province’, that is their sphere of operations, but Megellus fell seriously ill and remained in Rome until August. Regulus invaded northwest Samnium but his route of advance was blocked by a Samnite army. Unable even to forage he was contained in his camp and early one morning, taking advantage of thick fog, the Samnites made a daring raid. Dispatching unsuspecting sentries, they entered the camp by its rear gate, killed Regulus’ quaestor Opimius Pansa and more than 700 legionary and allied troops (Livy reports the presence of a Lucanian cohort and Latin colonists from Suessa Aurunca). Regulus was forced to retreat back to the territory of Sora. The Samnites followed, but dispersed when Megellus finally joined his colleague at Sora sometime after 1 August (on that day the consul is recorded as dedicating his temple to Victoria in Rome). Megellus proceeded to besiege Milionia, while Regulus marched to relieve Luceria. Regulus’ luck did not improve in Apulia. The Samnite army met him at the frontier of Luceria’s territory, defeated him in battle and his legions and cohorts retreated into their fortified camp. The following day, only after much cajoling by the consul, senior officers and centurions, was the army persuaded to resume the fight. It seemed that the Romans would again be defeated, but Regulus’ loud declarations that he had vowed a temple to Jupiter Stator (‘the Stayer’) in exchange for victory, and the exemplary leadership of the centurions, encouraged the Romans, who enveloped the Samnites and finally won the fight. The surviving Samnites, 7,800 in number, were not enslaved but stripped and forced under the yoke. They were defeated and humiliated but free to return to Samnium. Regulus was now keen to return to Rome and claim the right to triumph. On route, he intercepted and slaughtered Samnite raiders in the territory of Intermna Lirenas (the Samnites were perhaps making their way down to northern Campania), but when the Senate learned that he had lost almost 8,000 men in the two-day battle near Luceria and, even worse, that he had let the enemy go free, his request for a triumph was rejected.

The Senate and some of the plebeian tribunes who represented the People also denied Postumius Megellus’ request for a triumph, but the arrogant and unconventional patrician held one anyway on 27 March 293 BC, perhaps suggesting that he campaigned through the winter months. He had, after all, stormed Milionia, killed 3,200 Samnites and enslaved another 4,700; he captured another Marsian (or Samnite) town called Feritrum and enriched his troops with booty; advancing into Etruria he defeated the army of Volsinii and then he captured Rusellae, no mere hill fort or town like the strongholds of the Aequi or Samnites, but a great fortress city. It had been more than a century since the Romans last captured such a city (Veii). The Etruscans had believed their cities impregnable and the war in Etruria lasted so long simply because the Etruscans could retreat behind their strong walls, just as the army of Volsinii did in 294 BC when defeated in the field by Megellus. It is to be regretted that no details of how exactly Megellus captured Rusellae survive; we know far, far more about the capture of obscure Milionia. However, such was the shock and surprise at his conquest of Rusellae that Volsinii, Perusia and Arretium sued for peace. On supplying the consul’s soldiers with clothing and grain, the Etruscans were permitted to seek terms from the Senate. They were granted truces of forty years’ duration, but each state was forced to immediately pay an indemnity of 500,000 asses. Readers will recall that Fabius Rullianus had extracted 539,400 asses from Perusia in ransoms in the previous year.