Vice-admiral Trevylyan-Napier

HMS Calypso at the battle, during which she was severely damaged, drawn by William Lionel Wyllie

In November 1917 it was the turn of the Grand Fleet to launch a major operation. This was to be a large scale attack on the German minesweeping operations in the North Sea. For some time these had been escorted by light cruisers and destroyers; more recently it had been observed that they were increasingly being supported by an entire battle squadron from the High Seas Fleet. The possibility of being able to engage this meant that a very substantial force must be committed to the operation. Madden, as commander of the 1st Battle Squadron, was to take overall charge of the attack, designated as ‘Operation FR.’

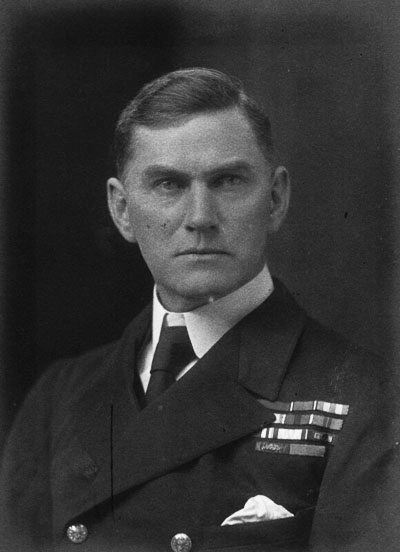

The vessels to be employed would be divided into three groups. Force A, under Vice Admiral Sir Trevelyan Napier, comprised his 1st Cruiser Squadron (Courageous, his flagship, with Glorious and four screening destroyers); 1st Light Cruiser Squadron (Cowan) (four light cruisers and two destroyers); and 6th Light Cruiser Squadron (Alexander-Sinclair) (four light cruisers and four destroyers). Force B, commanded by Pakenham, consisted of his 1st Battle Cruiser Squadron of four battle cruisers, reinforced by New Zealand, and the light cruiser Champion with nine destroyers. Force C was Madden’s 1st Battle Squadron, with eleven destroyers, which was to play a supporting role. Forces A and B, together under Pakenham’s command, were to sail from Rosyth and arrive at a point ‘about half way across the outer edge of the quadrant of mines in the Helgoland Bight. They were to approach this point from the western and southern sides of the large German minefield in the central part of the North Sea.’ Thereafter, they were to sweep NNW at high speed. They were to be in position by 8.00 am on November 17. Force C was to take up its supporting position at the same time. Madden’s written orders, issued on November 16, had originally prescribed 10.00 am for the cruisers’ rendezvous, but this was brought forward. Two submarines were patrolling to give intelligence of enemy movements.

The plan was, however, marred by a remarkably bad piece of staff work, the significance of which was explained in detail by Newbolt:

As the squadron commanders were instructed to strike at a force of enemy ships on or near the outer edge of the mine barrier, it followed that if it found them, the British squadrons might be obliged to press on into the mined area in pursuit. If they were so compelled their movements would obviously be restricted by those minefields which they believed to lie within the zone of their operations.

The Admiralty, in the person of the Hydrographer of the Navy, issued a monthly chart showing the British and German minefields in the Heligoland Bight. A copy went to the Commander- in-Chief, but it was not circulated to the fleet. Pakenham had either been given a copy or at any rate had seen one; but it was not shown to the admirals commanding cruiser squadrons. They, and their captains kept their own charts, updated by the ‘mine memoranda’ issued from time to time by the C-in-C. Unlike the monthly chart which he had, these memoranda did not locate the lines of mines laid, but merely indicated dangerous areas. The chart which Pakenham possessed or had seen showed a zone of clear water to the southeast of the general rendezvous. Pakenham therefore knew that his squadrons could safely go into the mined areas for some thirty miles, but Napier was quite unaware of this. What he did know was that Beatty had banned operations beyond a line just south of the rendezvous unless the ships involved had full information as to the minefields.

Napier’s chart differed from those in the possession of Alexander-Sinclair and Cowan, in that it marked as a danger area a 1915 minefield in the centre of the Heligoland Bight, which had been strengthened in July 1916. This large danger area was, Napier considered, an absolute barrier to further advance; on the other hand, the light cruiser squadron commanders knew nothing of it.

In addition there existed a chart showing the approximate positions of the German swept channels. Beatty had a copy, but he showed it to none of the admirals taking part in Operation FR. Madden’s orders of November 16 stated, under the heading of ‘enemy intelligence,’ that ‘enemy submarines on passage are following the route from Muckle Flugga to the Doggerbank Nord light vessel.’ He gave no information as to the likely enemy movements or lines of retirement. Taken overall, these lapses in efficient preparation for a major operation were inexcusable.

There was no doubt a good deal of discussion between the commanders while the operation was at the planning stage, at which the objective would have been thoroughly explored. All the same, Madden’s order of November 16 was laconic in the extreme, and cannot have helped Napier much with the decisions which he would have to make once the operation was under way.

At all events the British forces intended to take part in the operation duly assembled at Rosyth, and all of them left harbour at 4.30 pm on November 16. By 7.00 next day the cruiser groups were approaching the barrier. Napier, with the 1st Cruiser Squadron, was leading the way, with Alexander-Sinclair’s 6th Light Cruiser Squadron on his port beam and Cowan’s 1st Light Cruiser Squadron some three miles astern. Pakenham, with the battle cruisers, was steaming ten and a half miles on the port quarter of Courageous. Apart from some indications of wireless traffic which had been picked up during the morning watch, there was nothing to indicate that German forces were at sea in the vicinity. Visibility was about seven and a half miles; the sea was smooth and light, and the westerly wind was force two.

As it happened, the Germans had planned a large minesweeping operation for October 17 in the very sector to which Pakenham’s forces had been directed. This involved three minesweeping half-flotillas, and two destroyer half flotillas, reinforced by two additional destroyers, making eight in all, and a barrier breaking group, consisting of mine explosion resistant trawlers. The covering force was the Second Scouting Group under von Reuter, consisting of the light cruisers Königsberg, Nürnberg, Pillau and Frankfurt. There were two battleships, Kaiserin and Kaiser, in support near Heligoland.

The objective of the German operation was to obtain accurate information as to the whereabouts of British minefields, and to devise ways of circumventing them. Once the location of all of these had been identified, it would next be necessary to determine which should be cleared away. The operation on November 17 was aimed at searching from about the centre of the line Horns Reef – Terschelling in the direction N by W. Reuter ordered his group to assemble at 7.0 am; Captain Grasshoff, of Kaiserin, reported that at that time the two battleships would be in position west of Heligoland. Airship reconnaissance was impossible due to the thick weather, which also prevented Reuter shipping any seaplanes on his light cruisers; sea planes were, however able to fly from Borkum.

Aboard his flagship Königsberg, Reuter saw that two of the minesweeping half flotillas had not by 7.30 am, yet reached the rendezvous, and since they could not be far behind, he turned away from the rest of his squadron to bring them up. As he did so he suddenly came under fire from the NW; Napier’s flagship Courageous and her consort Glorious had sighted Königsberg on their starboard bow, and at 7.37 opened fire with their 15-inch guns. They were aided by the fact that whereas the western horizon was misty, obscuring the German’s ability to discern them, the eastern horizon was bright; the German vessels showed up distinctly. The surprise was complete; but the German destroyers and minesweepers at once made smoke screens, and by 7.51 the German ships were lost to sight. Reuter ordered the German cruisers, which had advanced to cover the retreat of the minesweepers, at 7.53 to turn southeast through the British minefields, falling back towards the support of the two battleships. One armed trawler, Kehdingen, had been serving as a mark boat for the sweeping forces; anchored in her position, she was hit almost at once by a shell, and thereafter lay immobile.

Although Napier had achieved a surprise of the enemy, he was far from clear about what he had encountered. Soon after opening fire he reported to Madden that he had an unknown number of light cruisers in sight, bearing east. Pakenham picked up the signal, and almost at once heard the sounds of gunfire, but was uncertain as to the enemy’s strength. A report from Cowan at 7.45 that the enemy bore ESE was accompanied by a warning that he could not tell how many enemy ships were present, so Pakenham was still none the wiser.

Nor was Napier, whose first report to Pakenham after the action was extremely inaccurate:

Soon after 0730 the enemy were sighted ahead consisting of five to eight submarines escorted by two or more destroyers, some minesweepers to port of them, and four light cruisers gradually coming into view to starboard of them. Four of the submarines appeared to be of unusually large size, either with funnels or with two conning towers and no masts. The light cruisers were probably Stralsund, Pillau, Regensburg and one other.

He went on to describe how these entirely fictitious submarines began to submerge and, more accurately, how the minesweepers disappeared NE while the destroyers made smoke:

The smoke screen was skilfully managed by the enemy, and soon reduced the shooting greatly to a matter of chance, crippling the range finding and spotting, and the point of aim was often only flashes.

When, at 8.00 am, Napier reached the smoke screen he turned sharply to the south. Once clear of the smoke, at 8.07 he sighted Reuter’s cruisers to the southeast of him, apparently heading ENE. Four minutes later he could see that they had turned southeast, and he reported these sightings to Madden. Pakenham, picking up these messages, ordered Rear Admiral Phillimore, in Repulse, to steer to the support of Cowan’s light cruisers, and turned his remaining battle cruisers to port to follow Napier. In his report to Beatty, Napier described how the action had now ‘settled down into a chase at ranges of 15,000 to 10,000 yards, the enemy still making heavy smoke, and steering down what was probably a swept channel as a pillar buoy was passed presumably marking an outer end.’

Although Reuter, having turned to the southeast, had completed his concentration, and his auxiliary forces were safely retreating to the north east undisturbed, his position was still hazardous. He had drawn all Napier’s forces after him, and could now only head for the support of Kaiserin and Kaiser as fast as he could. Newbolt points out the danger that he faced from the heavy guns of the light battle cruisers:

He was being followed by a force of overwhelming strength; and although he had gained a forward position against which the British broadsides could not be brought to bear, the forces against him were so numerous and powerful that a single mischance might bring disaster on his squadron. One 15 inch from the Courageous or Glorious, falling in the after part of any of his ships, might at any instant reduce her speed by a few knots: if it did he would have to abandon her as Hipper had abandoned the Blücher nearly three years before.

By 8.20 Reuter was under very heavy fire from all three British squadrons. Early in the engagement Ursa, one of Napier’s destroyers, had launched one torpedo unsuccessfully; now Vanquisher and Valentine, two of Alexander-Sinclair’s destroyers, attempted a torpedo attack but were driven off under heavy fire. Reuter now put up another smoke screen, and the two forces steamed on, with the British steadily reducing the range. Fifteen minutes later, as the smoke had cleared, Reuter again put up a particularly dense smoke screen, behind which his forces entirely disappeared. This gave Napier a problem. All the time he could directly follow Reuter he could safely assume that he would pass through waters that had been cleared of mines; now, this huge smoke screen might be intended to conceal a crucial change of course. Napier was approaching a line marked on his own chart, labelled ‘Line B,’ which he had drawn to show the point twelve miles beyond the rendezvous which, as he later wrote to Beatty, was ‘the limit I had in mind of, at any rate, British minefields, and to which I could go if necessity arose.’

To continue on his present course was obviously dangerous, and at 8.40 Napier turned his squadron eight points to port, to a north easterly course; Cowan and Alexander-Sinclair followed suit. At this point Courageous was about two and a quarter miles north of the two light cruiser squadron; Cowan was just then crossing the stern of Alexander-Sinclair at a very short distance while Repulse, which had not yet come into action, was six miles on the port quarter of Courageous. Napier reported to Madden that he had lost sight of the enemy, but that the light cruisers were in pursuit.

Twelve minutes later the smoke screen began to clear, and Napier could see that Reuter had, in fact, continued on his course; he altered course eight points to starboard and resumed the chase, having lost five precious miles by his original turn. By now the 6th Light Cruiser Squadron was in the lead, having had to make the smallest turn, and it was upon the ships of Alexander-Sinclair that Reuter’s vessels concentrated their fire. Cardiff sustained three hits, one on her forecastle, which started two fires, one on her superstructure above the after control position, and one in her torpedo department.

At 9.00 Phillimore, in Repulse, had finally caught up. He had been warned by Pakenham not to take her into the minefields, which the British were fast approaching and which obviously presented serious hazards. Pakenham had taken in Napier’s report that he had lost sight of the enemy, and was extremely anxious about the risks that were being run:

Although he possessed better and more detailed information with regard to the minefields than any of the other Admirals in the operating squadrons, Admiral Pakenham was very doubtful whether any good purpose would be served by pursuing the enemy through the intricate and twisting passages through the fields … now, on receiving Admiral Napier’s signal, he decided that our pursuit of the enemy ought to cease. The signal read as though contact with the enemy had been completely lost, and gave him no inkling that the enemy had temporarily disappeared behind a smoke screen; he therefore ordered all squadrons to join him at the general rendezvous.

Napier got this recall at about 9.00 am, by which time all the British ships, now including Repulse, were again in action. He was reluctant to comply, having just decided to advance further into the minefields. He thought, incorrectly, that Reuter had been reinforced, and that Alexander-Sinclair and Cowan would continue to need the support of his 15 inch guns; accordingly, in two messages to Pakenham he said that he had sighted the smoke of six ships ‘in addition to those reported at 7.30,’ and that he was still engaging the enemy. Accordingly, he did not act upon Pakenham’s signal of recall, and pressed on. This was in spite of the fact that following the turn to port Courageous and Glorious had fallen back so far that at 8.07 they were obliged to cease fire. In addition, the 4 inch guns of the Galatea class cruisers (Galatea, Royalist and Inconstant) were also out of range, only their two 6 inch guns being effective.

Just now, Reuter decided to launch a torpedo attack to slow down the British pursuit, under cover of a fresh smoke screen at about 9.15. For the next ten minutes torpedo tracks were repeatedly sighted by all three squadrons. Scheer records that six torpedoes were fired by the German destroyers, and that Königsberg and Frankfurt also fired torpedoes; but none hit.

It was not at all clear what hits had been scored on the enemy, although British fire control officers believed that one light cruiser had been damaged. At 9.30 Reuter again made smoke, preparatory to launching a fresh torpedo attack; again, no hits were recorded. By now, however, Napier had reached a point which he had marked on his map as ‘Line C,’ representing a ‘dangerous area;’ it was in fact a British minefield laid in 1915, and it was, for Napier, the absolute limit of his advance. At 9.32 he ordered his own squadron to turn sharply to starboard. Eight minutes later he signalled Pakenham and his own light cruiser squadrons: ‘Battle cruisers and cruisers should not go further through the minefield. Light Cruisers use discretion and report movements.’ At 9.49, he signalled Repulse: ‘Heavy draft ships should not go further into minefields.’ Since neither Alexander-Sinclair nor Cowan had the danger zone marked on their maps, they carried on the chase, trusting to their quarry to lead them through safe waters. Repulse appears to have continued to follow them, and all concerned had high hopes of achieving a decisive victory.

Reuter, too, now felt able to hope of achieving a success, as he wrote in his battle despatch:

Up to this point the action had been fought with a calm that may well be called exemplary. Everyone manned his post, carrying out the duties assigned to him as in manoeuvres. In spite of the tremendous impression caused by the mixed salvoes and the ensuing effects of the enemy’s fire… we were animated only by the fervent desire, filled only with the one thought: to destroy the enemy. This moment had arrived; calm yielded to a certain feverish expectation. It could only be a matter of minutes until the fate of the enemy was sealed.

His optimism was justified; with the British light cruisers in hot pursuit of him, there was every chance that he would be able to deliver them to Kaiserin and Kaiser. If they tried to escape by turning north or northwest, they would be heading straight into the minefields, where they might suffer heavy losses.

SMS Kaiser Kaiser and Kaiserin were assigned to security duty in the Bight on 17 November; they were tasked with providing support to II Scouting Group (II SG) and several minesweepers. Two British light cruisers, Calypso and Caledon, attacked the minesweepers and II SG in the Second Battle of Helgoland Bight. Kaiser and her sister intervened and hit one of the light cruisers. The two ships briefly engaged the battlecruiser Repulse, but neither side scored any hits and the German commander failed to press the attack.

In the ongoing exchanges of gunfire between the respective light cruisers, Calypso suffered serious damage when a shell hit the conning tower, destroying the bridge, and killing all those on the lower bridge and wounding her navigating officer and mortally wounding her captain. The other light cruisers pressed on until at about 9.50 am they found themselves under fire from Kaiserin and Kaiser. Alexander-Sinclair at once ordered his own ships, and Cowan’s squadron to turn sixteen points and make their way at high speed out of the trap into which they had nearly stumbled. Kaiserin got a shot home on Caledon, which caused no damage; as Königsberg turned to pursue the retreating British, she was hit by a shell from Repulse, which caused a fire in a coal bunker. No further pursuit was undertaken.