The reconquest of Hungary 1683–1718

Years of success 1683–1689

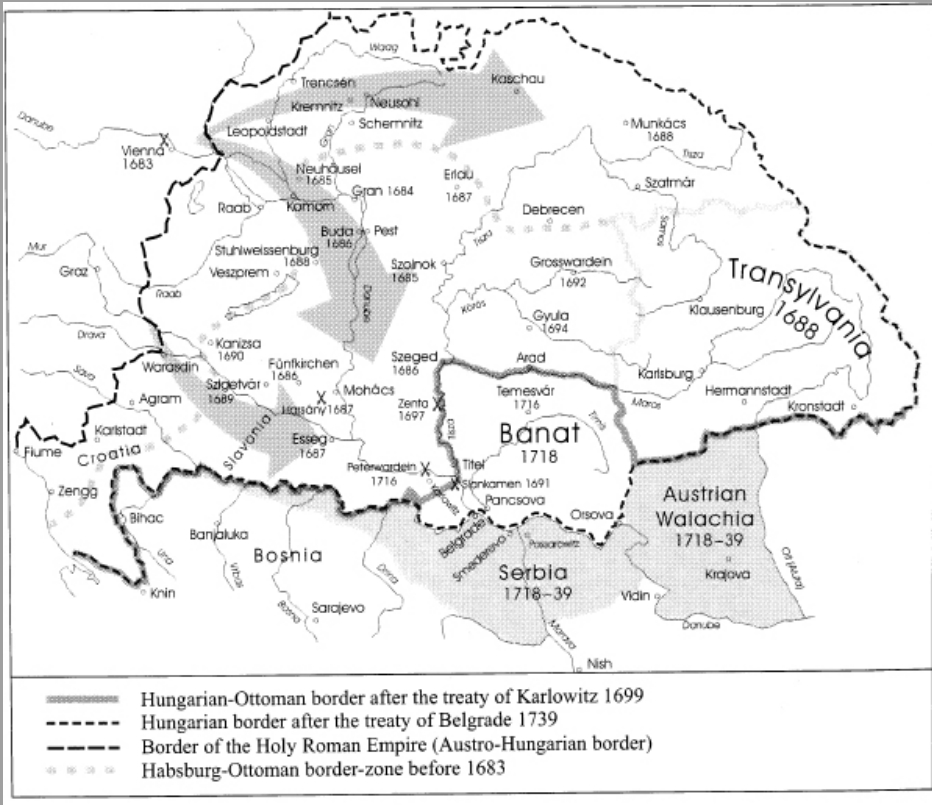

In autumn 1683, shortly after the relief of Vienna, the allied forces advanced into Ottoman Hungary. Following a clear victory at Párkány in early October, Gran was captured late in the same month and Thököly pushed back in Upper Hungary. In December 1683, the Sultan had the luckless grand vizier Kara Mustapha executed at Belgrade, while, on the Christian side, the Polish auxiliary troops returned home.

1684 saw a new ‘Holy League’ created under the auspices of the Pope. The Emperor, Poland and Venice signed an alliance (5 March 1684), while Russia joined the anti-Turkish coalition two years later. Though a coordinated strategy was beyond the new allies, the opening of additional theatres of war prevented the Turks from concentrating their forces on one target. Venice was now fighting the Porte at sea, in Dalmatia, Bosnia and on the Greek mainland, while Poland tried to reconquer Podolia (lost in 1676) and repeatedly invaded Moldavia, albeit with no lasting success. In order to be able to focus its efforts on the war against the Sultan, Vienna accepted that, for the time being, it could do nothing effective to resist Louis XIV’s annexations along the Rhine.

Nevertheless, the main thrust of the Imperial army’s three-stage campaign plan for 1684 met with no success. The main army with its 43,000 men under Charles of Lorraine was to take Ofen (Buda), with a small corps of some 11,000 advancing along the Drava against Esseg. Finally, a third corps (7,000 men) was to keep in check Thököly in Upper Hungary. While in June 1684 the main army managed to conquer Pest, the siege of Buda, started in mid-July, had to be abandoned in early November after heavy casualties.

Plans for 1685 again provided for a three-part offensive, with troops simultaneously advancing along the Drava, the Danube and in Upper Hungary. In August 1685 Neuhäusel was stormed, with Szolnok following in October. Significant progress could be made against Thököly in Upper Hungary, where the most important fortresses were now again in the hands of the Imperial forces. This marked the end of Thököly’s short reign. The Kuruc movement crumbled within a short time. Most of the Kuruc army and its leaders had deserted to the Imperial camp and were now fighting the Turks. Munkács, Thököly’s eyrie, alone held out until the beginning of 1688.

It was only in 1686 that the Hungarian theatre of war witnessed a real breakthrough. While the Polish troops had left the ranks of the Imperial auxiliary forces in the winter of 1683, Brandenburg rejoined the Imperial camp after a prolonged phase of pro-French orientation. Two treaties were concluded in January and March 1686, laying down that the elector was to send auxiliary troops of more than 8,000 men to Hungary in return for substantial subsidies and the cession of Schwiebus, a Silesian exclave on Brandenburg territory. After months of siege the Christian armies, mustering all their strength, finally succeeded in capturing Buda, the capital of Turkish Hungary (2 September 1686), with Hatvan, Fünfkirchen, Siklos and Szegedin following in October.

In return for putting auxiliary troops at the Emperor’s disposal, German rulers not only expected the stipulated subsidies but also a major command. In 1686 and again in 1687, the Bavarian elector thus created considerable problems and even operational confusion. In July 1687 the Christian main army was heading south along the Danube to capture Esseg. On 12 August 1687, at Harsány near Mohács, Charles of Lorraine defeated a Turkish army which had come to the rescue of Esseg and the nearby bridge over the river Sava, one of the most important Turkish supply points. After the victory, a smaller Christian corps managed to cross the Drava and occupied Esseg and Central Slavonia; in December 1687, far in the north, the Turkish stronghold of Erlau (Eger) capitulated.

Ever since 1685 Vienna had been trying to get Transylvania to join the ‘Holy League’ as a first step to re-integrate the principality smoothly into the Habsburg realm. Although Imperial protection, religious freedom, independence as well as recognition of Michael Apafy (1632–1690) as reigning prince of Transylvania and of his son and presumptive heir had already been granted by treaty (June 1686), Apafy’s position remained ambiguous. Jan Sobieski was also trying to turn Transylvania into a Polish protectorate and the Turks kept a watchful eye on their satellite as well. In October 1687 Charles of Lorraine invaded Transylvania, which was now forced by treaty to provide winter quarters – both provisions and cash – for sections of the Imperial army. In May 1688, Imperial diplomacy eventually succeeded in persuading Transylvania to break with the Porte, following which the Prince and the three ‘nations’ recognized the supremacy of the King of Hungary. In return, Michael Apafy retained his princely status and religious pluralism was guaranteed. Vienna had intended a similar approach for the Turkish tributary principality of Walachia, yet the corresponding treaty of January 1689 never came into force.

In 1688 the Christian armies’ central operational target was the major fortress of Belgrade commanding the confluence of the rivers Danube and Sava. The capture of Stuhlweißenburg in May 1688 seemed an excellent omen. With the Duke of Lorraine fallen ill, the main army, rallying at Esseg, was at last under the supreme command of Max Emanuel of Bavaria. After the capture of Titel in late July 1688, Belgrade was besieged from mid-August; it fell on 6 September 1688. Meanwhile, field marshal Ludwig Wilhelm von Baden, nephew of Hermann von Baden, president of the Aulic War Council, captured Kostajnica on the river Una before marching along the Una and Sava to occupy Gradisca and Brod (August 1688). Subsequently, he advanced up the Drina to Zvornik, which could be taken in mid-September 1688. In March 1689 the totally isolated fortress of Szigetvár finally surrendered to the Imperial troops.

Setbacks and stagnation 1689–1696

The success of 1686–88 encouraged inflated hopes of territorial gains in Vienna. Serbia, Walachia, Moldavia, and even Bulgaria, Bosnia, Albania, Macedonia and Thessalia conquered permanently or occupied until redeemed for enormous reparations – such was the heady prospect entertained by Austrian observers.

Reality, however, was quite different: in the summer of 1688, the Turks had sent a peace mission to Vienna, where it was stalled for several months. In view of France’s aggressive posture (p. 169), the Emperor’s council was more than ever divided into ‘easterners’ and ‘westerners’, with the two other leading Catholic courts, Spain and the Papacy, fighting on different fronts: Spain wanted Imperial support against France in the west, while papal diplomacy sought concerted action against the Turks and so sponsored a durable peace between Louis XIV and the Emperor. In spite of the dawning conflict with France – which naturally promoted Turkish hopes for relief – Vienna was ultimately unwilling to agree to Turkish demands. These were stiff given the Turkish defeats: Transylvania and Belgrade were to be handed back to the Turks, with all other Turkish-held fortresses in Hungary remaining in the hands of the Sultan. Vienna in turn made demands reaching far beyond the uti possidetis, and discussions broke down. In 1689 the Emperor embarked on a risky two-front war, hoping to wear down the Porte by further victories while simultaneously fighting Louis XIV. As 1690 showed only too clearly, this commitment on two fronts was too much for the resources of the Habsburg Monarchy and its small military establishment.

For a short time, the war in the west turned Hungary into a secondary theatre of war. Charles of Lorraine and Max Emanuel were fighting on the Rhine, and so Ludwig Wilhelm von Baden was nominated new commander-in-chief in Hungary, but now had no more than 24,000 men at his disposal, with another 6,000 being deployed in Transylvania. Numerous Imperial regiments as well as auxiliary forces sent by the Franconian and Swabian Circles left the Hungarian theatre to join the struggle against France.

Despite severe supply problems, Baden achieved a succès d’estime in the campaign of 1689. In August, he pushed through the Morava valley as far as Niš, where he crushed the Turks on 24 September and drove them back into Bulgaria. Baden then reached the Danube and in mid-October 1689 took Vidin by storm before occupying Kladovo. The Imperial forces intended to winter in Walachia – to spare exhausted Hungary, but also to underline Vienna’s claim to a ‘Greater Hungary’ including the neighbouring Turkish tributaries such as Moldavia and Walachia. Although agreement had been reached in a treaty imposed upon Walachia, the Emperor’s troops were not provided for when they entered the territory in late 1689. Even the punitive occupation of Bucharest could not alleviate the dismal supply situation, and early in 1690 the much reduced Imperial corps had to withdraw to Transylvania. This debacle was the first of a series of failures.

While marching towards the Danube, Baden had left behind a detachment of 8,000 men to hold Niš and to protect his flank. This Imperial corps, however, preferred to push expansion further south as far as Skopje and Prizren forcing the weak Turkish forces at first to retreat. In early January 1690, however, the latter annihilated a sizeable Imperial unit at Kacanik, forcing the Imperial troops in turn to retreat back to the Niš area. Only then did the situation stabilize, with retaliatory raids now leading the Imperial forces deep into Bosnia and Bulgaria. Not surprisingly, the successful Imperial advance into the Balkans encouraged the Roman Catholic Emperor to regard himself as patron of the region’s Orthodox Christians. Leopold was in direct competition with the Tsar in Moscow, to whom Orthodox Balkan Christians had been turning for protection since the late 1680s. In April 1690 Leopold issued a manifesto to the Christian peoples in the Balkans encouraging them to take up arms against the Turks. Yet the Imperial defeat and retreat in 1690 had changed the situation, exposing as it did the Slav population to Turkish revenge. Large-scale emigration from Serbia, Macedonia and the area around Novi Pazar had to be organized by the region’s Orthodox patriarch. Beginning in the summer of 1690, a maximum of 60,000–70,000 people – Serbs, but also Bulgarians, Macedonians and Albanians – were moved to the southern parts of Hungary but also as far north as Szeged and Arad, and even further north to Buda. In return for religious freedom, ecclesiastical autonomy and special Imperial protection – in other words the exemption from the Hungarian feudal system – the ‘Serbs’ were expected to reinforce the Emperor’s military forces. New sections of the Military Border established early in the eighteenth century were frequently manned by these Slav refugees of 1690. The migration also had significant long-term consequences: while the Slav element in the southern parts of Hungary was considerably strengthened, the Serbian heartland was resettled by Albanians – migratory movements whose repercussions were still being felt in the late-twentieth century!

The setbacks early in 1690 persuaded Baden to establish a defensive perimeter along the rivers Sava and Danube, particularly since the main army in 1690 numbered no more than 11,000 men (excluding borderers)! Transylvania, Upper Hungary’s glacis, had to be particularly protected, but it was too late: the major offensive launched by the Turks in the summer of 1690 resulted in a colossal military disaster for the Christian cause. While the grand vizier himself reconquered the Danube area, Imre Thököly, whom the Turks had appointed prince of Transylvania after Apafy’s death, invaded his new territory in August 1690 forcing the Transylvanian Estates to pay homage to him in September. Baden now counter-attacked vigorously, reasserting Imperial control over Transylvania by the end of December 1690. Further west, however, a series of disasters had occurred. In August/September the Turks had captured Vidin and Niš and then the undermanned stronghold of Belgrade on 8 October 1690. A Turkish advance on Esseg could be warded off, but the Turks in turn managed to relieve those fortresses north of the Danube which they still controlled: Temesvár, Gyula and Grosswardein. The fall of Kanizsa in March 1690 was thus but poor consolation for the Christian side.

Though Thököly’s invasion of Transylvania was a one-off, it had clearly demonstrated the instability of the situation in the region. In 1690 and again in 1691 the Emperor confirmed the Transylvanian liberties and constitution, in return for which Transylvania agreed to contribute a handsome annual sum to the Imperial treasury. In reality, the country’s period of semi-independence was over. Upon his death Apafy had left behind a minor son, Michael II (1676–1713), whose formal recognition as prince the Transylvanians could never obtain. In 1697, young Apafy renounced the Transylvanian throne and the principality became a firm part of the Habsburg realm. Regardless of Transylvanian privileges particularly in religious matters, the de facto occupation by Imperial troops resulted in Counter-Reformation measures. It was in vain that, with the help of the Maritime Powers, the Transylvanians tried to preserve a special status.

As for the campaign of 1691, it was clear that the emphasis had now to be put on the Hungarian theatre of war again, even if England and the Dutch Republic, the Emperor’s allies against France, were strongly pressing for peace in the east in order to free Austria’s resources for war against the Sun King in the west. By hiring auxiliary troops, increased recruiting and transferring units from the western theatre of war to Hungary the imbalance was to be set right, with an aim of raising the number of Christian soldiers deployed in Hungary and Transylvania to 75,000 men (excluding Hungarian irregulars and border guards), while a mere 8,700 and 14,500 remained for the Reich and Piedmont respectively. On 19 August 1691, the margrave of Baden, fittingly nicknamed ‘Türkenlouis’ for his victories over the Turks, crushed the grand vizier Mustapha Köprülü and his troops – far outnumbering the Imperial forces – in the battle of Slankamen near the confluence of the rivers Tisza and Danube. The grand vizier himself died in battle, but the Christian army also suffered heavy losses: 7,200 dead and wounded, almost a quarter of the field army’s strength; an advance on Belgrade was thus out of the question. Baden therefore turned against the Turkish-occupied fortress of Grosswardein, which capitulated only after many months of blockade early in June 1692. Otherwise the year witnessed few events worth reporting, apart from the fortification of Peterwardein on the Danube whose task it was to neutralize the fortress of Belgrade as far as possible; as early as 1694 it proved itself withstanding a major Turkish attack.

Slankamen was the last of Christian victories for some time to come; defensive warfare now became the order of the day. For the duration of the war in the west, French diplomacy did its utmost to keep the Turks fighting the Emperor. After the death of Pope Innocent XI, who had supported Leopold I’s Turkish war in all possible ways, financial help from Rome gradually petered out in 1689. Of paramount importance remained the support which the Emperor received from the Reich (the Diet voted 2.75 million fl. in 1686). After 1692 – following in the train of Bavaria, Saxony and Brandenburg – the newly created electorate of Hanover also decided to send a sizeable auxiliary corps of 6,000 men to the Turkish front. Each year of the war, between 20,000 and 40,000 men from the Reich reinforced the Christian troops in Hungary, before the outbreak of war with France in 1688–89 resulted in a dramatic, if temporary, cutback.

In 1693 the Emperor finally lost his ablest general to the Rhine front, where Baden took over command. Even so, attempts were made by the Imperial forces in Hungary in August and September 1693 to reconquer Belgrade, but to no avail. Meanwhile, Tartar forces invaded Hungary and devastated the tracts along the Tisza as far as Debrecen. As early as spring Christian forces had captured the Turkish enclave of Jenö north-east of Arad. After the fall of the fortress of Gyula (December 1694), Temesvár was the only place on Hungarian soil still in Turkish hands.

The campaigns of 1695 and 1696 were overshadowed by the blunders of the 25-year-old elector Friedrich August of Saxony as luckless commander-in-chief. In return for an auxiliary corps of 8,000 men he received not only 200,000 fi., but also the supreme command in Hungary. The Christian main army of some 50,000 men at first planned to besiege the isolated fortress of Temesvár, but the Turks seized the initiative. At the end of August 1695 they crossed the Danube at Pancsova, re-captured Titel and, near Lugos, wiped out an Imperial corps sent from Transylvania which had been unable to join forces with the main army.

In 1696 the Saxon elector again took command after increasing his auxiliary corps to 12,000; yet the siege of Temesvár, started back in August, failed once more. On the Black Sea, however, troops, albeit Russian ones, were favoured with greater fortune. After two unsuccessful campaigns against the Crimea in 1687 and 1689, Moscow had practically withdrawn from the war against the Porte. It was not until 1695 that Tsar Peter resumed operations, and in 1696 Azov could be captured. In February 1697, Russia, Venice and the Emperor entered into an alliance committing themselves to concerted action against the Sultan.

Unexpected triumph 1697–1699

After Jan Sobieski’s death in June 1696, the Saxon elector’s Polish ambitions pleased the Emperor not only because this prevented the French candidate from being elected; what was even more important was the fact that Friedrich August’s election to the Polish throne also freed Vienna from having to entrust an incompetent with the supreme command once more; the latter now passed to Prince Eugene of Savoy, previously commander of the Imperial forces in Piedmont. Descending from a collateral line of the dukes of Savoy and brought up at the French court, he was the son of Prince Maurice de Savoie-Carignan and Olympia Mancini, Cardinal Mazarin’s niece, as well as cousin to margrave Ludwig Wilhelm von Baden. In 1683, he entered Imperial service just in time for the relief of Vienna and soon made a career for himself, commanding a cavalry regiment by the end of the year and becoming general in 1685; as early as 1693, at the age of only 30, he was promoted field marshal.

Succeeding the Saxon elector as commander-in-chief in Hungary, Eugene was to be responsible for the crowning achievement in the Turkish war, which had been so unsuccessful in recent campaigns. Now that war in the west had ended new energy and resources could go to the Turkish front. On 11 September 1697 Eugene of Savoy and his 50,000 men caught the Turks on their way north at Zenta, while they were crossing the river Tisza; in the ensuing battle, the Ottoman army was annihilated. 25,000 Turks are said to have lost their lives, including the grand vizier. Sultan Mustapha II (1695–1703) escaped to Temesvár; by early 1698, he was already seeking English mediation to end the war. In early October 1697, Eugene, with a hand-picked army of 7,000 plus strong border units, embarked on a daring raid which took him up the Bosna as far as Sarajevo. The campaign of 1698 was as uneventful as its predecessors until the year of Zenta. Temesvár could still not be captured.

Early in October 1698, peace negotiations between the members of the Holy League and Constantinople opened at Karlowitz south-east of Peterwardein under English and Dutch mediation. Despite her military failures, Poland regained Podolia, while Venice was granted the Peloponnesus (Morea), additions to the Ionian Islands and frontier rectifications in Bosnia and Dalmatia. Russia and the Porte concluded an armistice in January 1699, followed by a definitive peace only in 1700, with Moscow at least temporarily gaining access to the Black Sea via Azov and Taganrog; by 1711–13, this had been lost again after a disastrous campaign against the Turks. Russia’s interest in access to the Black Sea reassured Vienna, which wanted to see the Tsar occupied as far away as possible. As early as 1698 Austria had advised Russia not to attack Moldavia and Walachia, considering these Turkish satellites to lie within her own sphere of influence. In the wake of the Polish election in 1697, Russia’s drive towards the west had become tangible, and during the Karlowitz negotiations the Tsar posed dangerously as protector of the Balkan Christians.

Imperialists and Turks signed their peace treaty on 26 January 1699. The whole of Hungary (with the exception of the Banat of Temesvár), Croatia and Slavonia (excluding a small tip of Syrmia near Belgrade) passed to Leopold I. Karlowitz was the first peace agreement where the weakened Ottoman Empire had to accept western mediation and also suffered considerable territorial losses. Hungary remained the focus of the Emperor’s armed forces. With peace-time strength reached after radical disarmament, more than 75 per cent of the armed forces were still quartered in the kingdom.