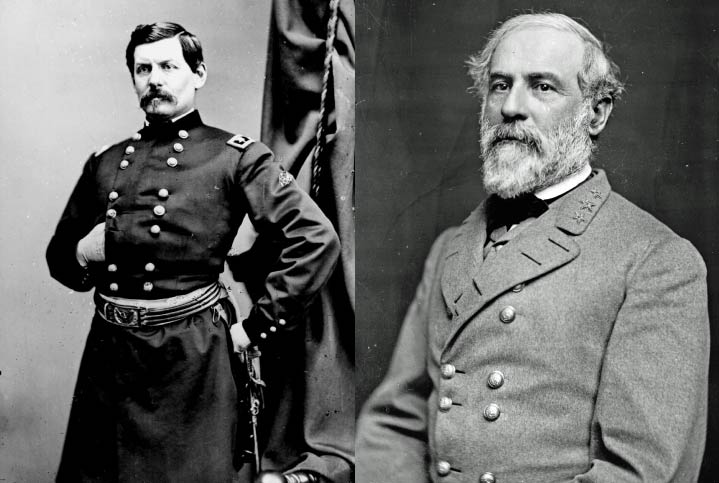

George B. McClellan and Robert E. Lee, respective commanders of the Union and Confederate armies in the Seven Days

Near the end of the fighting on June 1 General McClellan appeared on the battlefield. His lieutenants had matters well in hand and little required his attention. “Sumner and his generals press themselves around the General, excited and triumphant,” wrote the Comte de Paris, who went on to sketch the scene. Sumner “has an even more withered air than usual”; the Irish Brigade’s Thomas Meagher “caracoles from right to left, always followed by a big green guidon, as if to say . . . ‘I am the most Irish of the Irish’”; William French “twitches his nose and winks his left eye convulsively.” An exception to the animated group was “the silent and contrite figure of Couch, wandering in vain in search of his division . . . cut off the previous day.”

McClellan gave thought to striking at the retreating enemy with Porter’s and Franklin’s corps. But the river was reported running higher and more violent than ever, making bridging impossible. McClellan crumpled the dispatch in his fist, wrote the Comte de Paris, “but he limited himself to this gesture of impatience.” The Battle of Seven Pines would not be followed up.

On June 2 the general commanding issued an address to his troops. As he had promised, “you are now face to face with the rebels, who are at bay in front of their Capital. The final and decisive battle is at hand.” He asked of them one last crowning effort, and he renewed his pledge: “Soldiers! I will be with you in this battle and share its dangers with you.” Read to the troops at dress parade, it “was greeted by many and loud cheers,” wrote a staff man.

McClellan pledged to Washington as well. He claimed victory at Seven Pines and said he would move quickly to build on it. “I only wait for the river to fall to cross with the rest of the force & make a general attack.” He telegraphed his wife, “One more & we will have Richmond & I shall be there with Gods blessing this week.”

But that night, in his solitude, he turned introspective in a letter to Ellen. June 1 marked his first-ever look at the scene of a major battle. He found it deeply disturbing. The impression in his mind’s eye of Seven Pines was crowded with the images of hundreds of gravely wounded men awaiting care and, scattered across the muddy, trampled field, scores of killed from the previous day’s fighting. He had seen battle dead before, in Mexico, but this scene was different—different in scale, different because these killed and wounded men were his men. He was confident of ultimate success, he wrote. “But I am tired of the sickening sight of the battlefield, with its mangled corpses & poor suffering wounded! Victory has no charms for me when purchased at such cost.”

Seven Pines proved to be the only Peninsula combat George McClellan experienced this close up. His revulsion at the bloody arithmetic of battle pointed to something deep-rooted in his military character—a reluctance to accept the human toll necessarily expended by a commander to win a battle or a campaign. As he put it in another letter, “Every poor fellow that is killed or wounded almost haunts me!” In his address to the army he promised his men he would join them in the fighting to come and share its dangers. But critically at issue was whether in battle he would—or could—demonstrate the “moral courage,” the ruthless acceptance of responsibility, to risk and to expend those lives, in whatever numbers required, to gain victory.

McClellan’s incaution in pushing forward his left wing, and his misjudgment in thinking Johnston “too able” a general to risk countering that move, put the Army of the Potomac in jeopardy on May 31. Fortuitously, Johnston’s planning was so bungled that the Federals rallied and finally halted the assault, and then on June 1 regained the lost ground. From his sickbed McClellan’s direction was limited to ordering Sumner’s Second Corps to support the embattled left. The Federals lost 5,000 men and the Confederates 6,100, and the two armies ended the battle about where they began it.

In reporting to Washington on the fighting, McClellan drew on Heintzelman’s dispatches to denounce Silas Casey’s division for giving way “unaccountably & discreditably” on May 31. As at Williamsburg, McClellan’s report was highly judgmental of events where he was absent; and it too was released to the press. The press expanded the story. Correspondent Samuel Wilkeson pictured Casey’s troops as “sweeping in a great shameful flow down the Williamsburg road.” Casey’s men, wrote Wilkeson, “had been taught nothing save how to march and camp, and . . . deteriorated daily under the command of a General who had neither youth, enthusiasm, pride, or combativeness.”

Casey tried to defend himself and his men. Just because his division was “the subject of a false and malicious telegram, it is certainly no reason that it should be deprived of that which is justly its due.” He said his long casualty list earned his division credit, not discredit. The “unaccountably & discreditably” charge was withdrawn, but the damage was done. Beyond doubt Casey’s division had been severely handled. On June 23 McClellan relieved Casey, replacing him with John Peck. Casey would not again serve in the field. While the matter was handled awkwardly, McClellan’s summation was accurate enough. At Seven Pines “the division of Gen Casey was broken in such manner as to show that its commander had failed to infuse proper morale into his troops.”

Seven Pines was a battle suited to Bull Sumner’s dedicated if limited generalship. “The old man seemed to be making up for Williamsburg,” wrote Charles Wainwright. Scorched by the press after the earlier battle, Sumner sought vindication on May 31. When a McClellan dispatch crediting Sumner’s role in the fighting was garbled in the New York Herald, Sumner insisted McClellan make it public as originally written. He did so, and Sumner sent a copy to his wife endorsed, “Show this dispatch to our friends.” Alerted, he had assembled his men and marched them right to the Chickahominy bridges, thus wasting not a moment in crossing when the order came . . . saved moments that saved Keyes and Heintzelman. In the fighting Sumner grasped the measures needed, and competent lieutenants John Sedgwick and Israel Richardson carried them out.

The Comte de Paris, so contemptuous of Erasmus Keyes at Williamsburg, conceded that “General Keyes . . . this time is not afraid to expose himself” to enemy fire. Keyes’s horse and accouterments were hit three times by musketry during the chaotic fighting on May 31. A staff man wrote, “Keyes again rode up cheering and encouraging all around him, and his presence and words then as many other times during the day infused new vigor and determination into the men. . . .”

Still, Keyes found himself tarred by the same brush used on Casey, and belittled by the same rumors about his fortitude that Philippe earlier reported. Keyes wrote New York’s Senator Ira Harris that “great injustice has been done to my corps & to me in giving currency to the idea that Casey’s Division ran at once.” Most of the Fourth Corps, he insisted, was much longer under fire than that; he himself “was under hot fire for six consecutive hours on the 31st & . . . I personally reformed my lines many times.” But Erasmus Keyes had been caught in a situation not of his making, in a posting not of his choice, and could only try to stem what became (whether sooner or later) a stampede. To Chief of Staff Marcy, an old friend, Keyes wrote, “I cannot of course believe that Genl. McClellan is going to frown on me for my conduct on the 31st,” but should he in any way disapprove, Keyes appealed “to our old associations” to allow him to resign quietly and not suffer the humiliation of being relieved.

McClellan lacked cause to relieve Keyes, but he distrusted him sufficiently to post him in the coming weeks far from the sound of the guns. For his part, Keyes sought intervention from Treasury Secretary Chase: “I am called a Republican and if you know the manner in which McClellan & his clique make war on republicans, you will understand what pressure I am obliged to sustain.” He sought “the favor to have me ordered out of this army in some way which will not reflect on my capacity or devotion to the cause.”

Darius Couch, heading Keyes’s other division, was cut off at Fair Oaks Station with hardly a third of his command. He defended the spot stubbornly until Sumner came to his relief, and was not forgiving of McClellan’s failure to recognize his division’s hard fight. Like Keyes, he wrote privately to Chief of Staff Marcy: “If I am obnoxious to Gen. McClellan, let him send me to another field. I am willing to do anything, in order that the men know that they saved the left wing of the army.”

Sam Heintzelman initially reacted to the attack in slow motion, due to the ninety-minute delay in reporting from the front. But as he had at Williamsburg, he rushed to the scene, thrust himself into the fighting, pushed reinforcements forward and posted them, and his reporting brought Sumner’s Second Corps into the battle. McClellan held out his hand, Heintzelman wrote in his diary, “& remarked calling me by name, ‘You have done what I expected, you have whipped the enemy.’”

In answering the call on the 31st, Phil Kearny sought to reprise Williamsburg and play the part of rescuer. While he again demonstrated that as a battlefield leader of troops he had few peers, his command arrogance limited his performance. He overrode Heintzelman’s orders to David Birney merely on the grounds (as he told his wife) that “weak old fool” Heintzelman “mismanaged me as usual.” Kearny then did not admit it was he who was accountable for Birney’s supposed inaction. In his memoir Baldy Smith termed Phil Kearny “ungovernable,” a trait very much on display at Seven Pines.

In the second day’s fight there were no surprises by the Rebels, and no lapses by the Federal command. June 1 proved an incisive reversal of May 31. “I believe the report that the rebels are retreating,” Heintzelman wrote. “They cast their last die & lost.”

On May 30, as Joe Johnston prepared his assault on Seven Pines, far to the west in Mississippi P.G.T. Beauregard evacuated Corinth, slipping away from the clutches of Henry Halleck’s Federal army. This event triggered, on the part of General McClellan, an extended series of Beauregard sightings. Remarkably, the first came on May 30, McClellan reporting to Stanton, “Beauregard arrived in Richmond day before yesterday, with troops & amid great excitement.” On June 10 he passed on further intelligence of Beauregard’s arrival, and proposed “detaching largely” from Halleck’s army to strengthen his own. Halleck bristled, reporting Beauregard and his army still a presence in Mississippi. McClellan continued to post Beauregard sightings regardless, thereby considerably inflating the host defending Richmond.

As the Potomac army battled at Seven Pines, the campaign the president was managing in the Shenandoah Valley rushed toward its own climax. McDowell from the east and Frémont from the west sought to trap Stonewall Jackson. On May 30, having chased Banks into Maryland, Jackson started back up the Valley. By Jackson’s calculation, McDowell and Frémont were aiming for Strasburg, “and are both nearer to it now than we are.” In Washington, Quartermaster Meigs was writing, “Jackson’s army is being gradually surrounded. I pray that the movement may be successfully carried out & that he may be caught in the web we have woven with care and labor in the last week.”

McDowell’s 20,000 men in the Valley saw James Shields’s division in the van. Shields had just reached Fredericksburg to join the march to the Peninsula, but having campaigned in the Valley he seemed best suited to spring the trap. The Pathfinder, for all his experience in the mountains of the West, was finding the Alleghenies a terrible place to make war. Still, by May 31, despite their many trials, he and Shields were poised to head off Jackson at Strasburg. “It seems the game is before you,” Lincoln telegraphed them.

Then both Federal generals blinked. On June 1 Shields halted and turned to defend against James Longstreet’s command that rumor of the most improbable sort had brought from Richmond to threaten him. Frémont feebly skirmished with the Rebel rear guard while the last of Jackson’s troops hurried through Strasburg. “The latest information from the Shenandoah Valley,” wrote Lincoln’s secretary John Nicolay on June 2, “indicates that Jackson’s force has slipped through our fingers there, notwithstanding that he was almost surrounded by our armies.”

“Do not let the enemy escape from you,” the president demanded of McDowell and Frémont. They attempted pursuit, but on June 8, at Cross Keys, Jackson rounded on Frémont and drove him back. The next day, at Port Republic, Shields in his turn was driven back. A resigned Lincoln told Frémont to give up the chase and stand on the defensive. Shields was ordered to rejoin McDowell’s command. The Valley campaign was over, and Stonewall Jackson had won it decisively.

Lincoln’s directions to his generals in the Shenandoah reflected sound military instincts. He discounted Jackson’s threat to Washington, recognized Jackson’s intent to tie up Federal forces in the Valley, and without hesitation seized on the moment to cut off Jackson’s escape. Despite all the obstacles of terrain and weather, he managed to position Shields and Frémont in time to spring the trap. The failure was theirs. James Shields proved all bluster, Pathfinder Frémont, all excuses. Neither would redeem his lost military career.

The president’s strategy for energizing McClellan’s stagnant campaign went awry at the very start, when from the best of motives he pulled Shields’s division out of the Valley to join McDowell for transfer to the Peninsula. Had he not had to wait for Shields, McDowell and his three divisions at Fredericksburg ought to have joined McClellan by mid-May . . . at which Richmond, seeing the Yankees so strongly reinforced, would surely have recalled Jackson to defend the capital.

Lacking a general-in-chief, Lincoln’s only source of professional military advice was Stanton’s War Board and the ineffectual Ethan Allen Hitchcock. No one seems to have pointed out that without Shields’s division the Valley’s defenders were seriously “out of balance” and a tempting target for Jackson. “Messrs. Lincoln & Stanton are not as great Generals as they had supposed themselves to be,” remarked W.T.H. Brooks. John Gibbon wanted the war left to the generals, “who ought to know what they are about, and if they don’t I think it very certain nobody else does.”

In fact it was still possible to achieve an exalted state of reinforcement even after Jackson’s escape. George McCall’s division that had remained at Fredericksburg was started to the Peninsula (by water) on June 6. The president determined that Frémont and a rejuvenated Nathaniel Banks ought to be enough to keep a grip on the Valley, so on June 8 McDowell was directed to the Peninsula “with the residue of your force as speedily as possible.” That residue comprised the divisions of Shields, Rufus King, and James B. Ricketts (replacing E.O.C. Ord). But by now Shields’s division, in Lincoln’s homely phrasing, “has got so terribly out of shape, out at elbows, and out at toes” that it required refitting. Still, McDowell promised that he with King and Ricketts would join the Potomac army before June 20.

That order never came. Once again, affairs in the Valley turned perplexing. Lincoln told McClellan he had hoped to send him more force, “but as the case stands, we do not think we safely can.” The continued bumbling of Frémont and Banks kept the Valley’s defenses in disarray, and General Lee, with calculation, added to the perplexity. He dispatched three brigades to strengthen Jackson, greatly alarming the Yankees, then recalled Jackson and his entire command to the defense of Richmond. Frémont and Banks crowned their ineptitude by failing to discover that Jackson was gone.

Lincoln saw the reports of these Rebel reinforcements for the Valley as another McClellan opportunity. Every soldier sent away from Richmond was one less soldier the general would have to face—if he acted promptly. The logic of that quite escaped McClellan. Secure in his delusions about Confederate numbers, he replied that if 10,000 or 15,000 men “have left Richmond to reinforce Jackson it illustrates their strength and confidence.” Detective Pinkerton fed the general’s fantasy, reporting the Rebel army was “variously estimated” as 150,000 to 200,000 strong. McClellan took the 200,000 figure as his benchmark for the campaign.

During the First Corps’ checkered chronicle, Irvin McDowell met growing disdain from the Potomac army’s officer corps. McClellan was convinced of McDowell’s perfidy in angling for an independent command, and told Stanton if he could not have full control of McDowell’s men, “I want none of them, but would prefer to fight the battle with what I have & let others be responsible for the results.” Fitz John Porter tipped off New York World editor Manton Marble that McDowell was “a general whom the army holds in contempt and laughs at—and has no confidence in.” Israel Richardson spoke of “the gay and accomplished Gen. McDowell . . . who puts one in mind very much of a second Jack Falstaff. . . . We should like much to have his troops to assist us, but don’t want him.” McDowell wrote a friend, “Yet I, who have been striving and struggling to get down to join McClellan’s army . . . find myself thoroughly misunderstood both by the press and by the people . . . with a not worthy motive ascribed to me.”

The net result of Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley campaign was that his two divisions joined the Peninsula battles while just two divisions (of four) of McDowell’s reached McClellan. The unsettling situation sent the president up to West Point to seek counsel from the retired Winfield Scott. The old general advised dispatching McDowell’s corps to the Peninsula, and offered his thoughts on a general-in-chief and on a response to the Valley debacle. On June 26, the day after he returned to Washington, Lincoln combined the Union forces remaining in northern Virginia and in the Shenandoah Valley into a new Army of Virginia, to be commanded by one of Halleck’s Western generals, John Pope.

George McCall’s Pennsylvania Reserves division was assigned on arrival to the Fifth Corps. It boasted three promising brigadiers, John F. Reynolds, George G. Meade, and Truman Seymour. The Fifth was now the largest corps in the Potomac army and, under Fitz John Porter, the particular favorite of General McClellan.

McClellan gained a second substantial reinforcement by working himself free of General Wool at Fort Monroe. John Wool, seventy-eight, wily veteran of army politics, ran his Department of Virginia as an independent fiefdom, holding fast to his troops and deflecting McClellan’s pleas that he garrison the army’s rear areas at Yorktown, Williamsburg, and White House. Lincoln resolved the impasse by an exchange of department heads—Wool taking the place of John A. Dix at the Middle Department in Baltimore, Dix taking over at Fort Monroe. The Department of Virginia was folded into McClellan’s command, and two-thirds of Dix’s troops—eleven regiments—attached to the Potomac army. Dix’s regiments and the 20,000 men of McCall’s division, said Sam Heintzelman, “ought to carry us into Richmond.”

Edwin Sumner was given charge of the three corps now posted south of the Chickahominy—his Second, Heintzelman’s Third, Keyes’s Fourth. Armed with semi-independent status, Sumner resumed his alarmist habits. On June 1, even as the Rebels’ retreat ended the Seven Pines fighting, he announced, “I have good reasons to believe that I shall be attacked early in the morning by 50,000 men,” and he called out the Third Corps for support. Heintzelman disagreed, detailing his reasoning to Sumner. It was wasted effort. On June 3 Heintzelman’s diary read, “The promise of a pleasant day till Sumner created, or rather tried to create, a stampede.” June 8: “Gen. Sumner has another stampede & paraded his troops & Kearny’s. I could not see the slightest necessity.” Sumner was only calmed when McClellan shifted headquarters south of the river and the three corps commanders resumed their normal roles.

Phil Kearny loudly complained about Sumner (“Bull in a china shop”), and raised objection when John C. Robinson replaced the injured Charles Jameson as head of one of Kearny’s brigades. Robinson was a veteran officer with a good record, and Kearny was rebuffed. “Gen. McClellan has written a letter & sent it through me,” Heintzelman wrote, “as severe & unexceptional as a letter well can be written. It will do Kearny good. He is always finding fault & making exceptions.”

No objections met two other new brigade commanders. John C. Caldwell replaced wounded Otis Howard in the Second Corps. Caldwell was a school principal from Maine, a Republican whose party affiliation gained him the colonelcy of the 11th Maine and a promotion to brigadier general. Charles Griffin, the fiery artillery veteran who lost his battery at Bull Run, gave up the guns for an infantry brigade (and a brigadier’s star) in the Fifth Corps, replacing the promoted George Morell.

On June 2 headquarters set forth a reorganization of the Army of the Potomac’s artillery arm. On taking command, McClellan had shifted the assignment of batteries from brigade to division, with a general army artillery reserve. In the new scheme, each corps took roughly half the batteries assigned to its divisions to form a corps artillery reserve. The Second, Third, and Fourth Corps carried out this reorganization in time for the next battle. Porter’s Fifth Corps, to which Henry Hunt’s artillery reserve was attached, had no separate corps reserve. The thought here was to give the corps commanders more flexibility for tactical purposes. The guns still remained under control of infantry generals, however; artillery flexibility directed by artillery officers was yet to come.

So soon as the Chickahominy flooding subsided, McClellan put his engineers to bridge building. By mid-June there were ten bridges, and Franklin’s Sixth Corps was brought across. Only Porter’s reinforced Fifth Corps remained north of the Chickahominy, guarding the right flank and the railroad. The four corps south of the river entrenched themselves. Francis Barlow grumbled that the army lay crouched behind earthworks along the whole line. “I don’t know whether we are to be the attacking or the attacked party.” Phil Kearny grumbled too. “We always seem to take a nap after every Battle, which thus completely throws away all the good results.” Still, confidence was building. “Richmond is sure to fall,” Hiram Berry wrote. “. . . I trust when Richmond falls the war closes.”

On June 15 McClellan outlined for his wife, but not for Washington, his plan for capturing Richmond. Lincoln was given only the vague assurance that “we shall fight the rebel army as soon as Providence will permit.” The site of the next battle, McClellan told Ellen, would be Old Tavern, elevated ground a mile south of the Chickahominy and some five miles from Richmond. “If we gain that the game is up for Secesh—I will have them in the hollow of my hand.” At Old Tavern he would mass 200 guns to “sweep everything before us,” then advance the heavy guns and mortars and invest Richmond—“shell the city & carry it by assault.”

Much to McClellan’s embarrassment, on June 12–15 Jeb Stuart expanded a reconnaissance into a complete circuit of the Army of the Potomac. General Lee concluded that “McClellan will make this a battle of posts. He will take position from position, under cover of his heavy guns, & we cannot get at him without storming his works. . . .” Lee determined to seize the initiative. He took as his target Porter’s Fifth Corps north of the Chickahominy, and assigned Stuart to reconnoiter. The Rebel troopers traced Porter’s lines, and to conceal his purpose Stuart continued on around the Federals, returning to Richmond along the bank of the James.

Pursuit was a family affair, directed by Philip St. George Cooke, head of the cavalry reserve and Stuart’s father-in-law. Cooke set off on Friday the 13th and his luck foundered. Lacking an independent cavalry force like Stuart’s, Cooke had to paste together a command. Then he was hobbled by faulty intelligence that gave the Rebel column an infantry component. Cooke ordered up infantry of his own—Gouverneur Warren’s brigade—thus limiting the pace of the pursuit to that of the foot soldiers. He never came close to catching Stuart. “I have just returned after a weary tramp (and an unsuccessful one foolishly managed) . . . ,” Colonel Warren reported; “the rebels have been quite enterprising.”

Set against Union successes in other theaters that spring, the drumbeat of demands and complaints and excuses from the Peninsula increasingly wore on Washington. John Nicolay invoked an 1862 version of Murphy’s Law: “McClellan’s extreme caution, or tardiness, or something, is utterly exhaustive of all hope and patience, and leaves one in that feverish apprehension that as something may go wrong, something most likely will go wrong.” Quartermaster Meigs was sure “McClellan never did & never will give an order for attack.”

For his part, McClellan shared his alienation with his lieutenants. George Meade wrote his wife that he and Franklin and Baldy Smith visited McClellan, who “talked very freely of the way in which he had been treated, and said positively, that had not McDowell’s corps been withdrawn, he would long before now have been in Richmond.” McClellan passed on to Ellen the latest capital gossip: “I learn that Stanton & Chase have fallen out; that McDowell has deserted his friend C & taken to S!! . . . that Honest A has again fallen into the hands of my enemies & is no longer a cordial friend of mine! . . . Alas poor country that should have such rulers.” He named caution his watchword: “When I see such insane folly behind me I feel that the final salvation of the country demands the utmost prudence on my part & that I must not run the slightest risk of disaster. . . .”

Fitz John Porter took up his commander’s cause with virulent dedication. He urged New York World editor Marble to reveal to the country the nefarious conspiracy of the Lincoln administration. “The secy and Prest ignore all calls for aid. They have been pressed and urged but no reply comes. . . . I wish you would put the question,—Does the President (controlled by an incompetent Secy) design to cause defeat here for the purpose of prolonging the war, or to have a defeated General and favorite (McDowell) put in command . . . ?”