VETERANS IN THE CIVILIAN WORLD

Veterans might return to their old homes, settle near the forts where they had served or move to a colony – unless of course they chose to re-enlist. For a state that had virtually no other means of asserting and exerting its power over the general population other than through the army, colonies of veterans were a vital resource. They created settlements where thousands of trained and experienced men, loyal to the Roman state, could act as a military reserve. A rebellion by the Salassi tribe in north-western Italy provided Augustus with the opportunity to do just that. Once the revolt had been crushed, land was seized to settle veterans from his Praetorian Guard. The new city was named Augusta Praetoria Salassorum (Aosta), and local men of military age were cleared out by being sold into slavery. In Britain following the invasion of 43 a new colony at Colchester was established in 47 after Legio XX was sent out to campaign in the west, showing that it was an early priority. The archaeological remains have revealed that the colonists made use of the fortress’s lay-out and some of its buildings as they converted the site into the beginnings of a fully-fledged Roman town in a remote province.

Lucius Poblicius of the Roman Teretina tribe was a veteran of Legio V Alaudae, based at Xanten, which disappeared from history by the late first or early second century AD. His exceptionally impressive first-century tomb showcased the status he must have reached in the veteran community in the city he knew as Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippensium (Cologne), where he was buried. A substantial podium with pilasters contained Poblicius’ cremated remains and those of his children, his wives and his freedmen, while statues of Poblicius and family members stood on the podium between four Corinthian columns which supported an elegant tapering roof flanked by sphinxes.

Other veterans attained similarly high status in the civilian world. Lucius Silius Maximus was a veteran of Legio I Adiutrix at Alba Julia in Dacia. After retiring he moved to the canabae of the fortress where he served as a magistrate in the civilian settlement, ‘the first’ said to have done so. His new job represented an early stage in the settlement’s history. It would later earn formal incorporation under Marcus Aurelius. A dedication by Marcus Lucilius Philoctemon records that he was a senior civic magistrate, duumvir, of Alba Julia. Having been honourably discharged from service with Legio V Macedonica, Gaius Valerius Pudens likewise moved a short distance to the legion’s fortress canabae at Iglitza on the Danube, where in 138 he was serving as one of the settlement’s magistrates alongside colleagues who were civilians but may also have been veterans. Pudens must have done well to have fulfilled the necessary property qualification for civic office – whatever that was in this location. The text recorded an unspecified building given by Pudens, his senior magistrate colleague Marcus Ulpius Leontius, and the settlement’s aedile Aelius Tucce to the veterans and citizens of the canabae. The structure was dedicated to Hadrian, sick at the time and approaching death, but who of course had also served in Legio V Macedonica as tribune during its time in Moesia Inferior. Perhaps Pudens and the emperor were known to each other because Hadrian, who was said to have had a remarkable memory, ‘even knew the names of the veterans whom he had discharged at various times’.

At Capua a veteran called Lucius Antistius Campanus was honoured by the magistrates of the city when he died. He was ‘an excellent man’, they said, who had completed his military service ‘during hard and dangerous campaigns’ in their testimonial. Exactly when he retired is unknown but he seems to have earned the admiration of both Caesar and Augustus; most likely he served under Caesar in the mid-40s BC and under Augustus into the 20s BC. He was then settled by Augustus at Capua and perhaps lived into his eighties, since one restoration of the text suggests that his death came after 14 when Augustus died and was deified. Antistius Campanus, said the dedication, had generously spent his own money on various local causes ‘for everyone’s benefit’, rather than only that of his own family, as well as working hard for the community even though he was getting on in years. He almost certainly served in all the civic magistracies. The senior civic duoviri magistrates voted that his body be carried from the forum to the place of cremation, and that a gilt statue be erected to commemorate him and record the decree by the town council in his favour. Finally, they voted that he be buried in a suitable plot by the Via Appia, the road that led to Rome from Capua. Antistius Campanus of course did benefit his family. In 13 BC his son of the same name was serving as one of the duoviri at Capua and participating in the dedication of a temple of Jupiter and the Lares.

Many veterans established families and futures like Antistius Campanus. Others were not so lucky. Gaius Aeresius Saenus, a veteran of Legio VI Victrix at York, commissioned a tombstone for his family and, in anticipation of his own demise, himself. This grieving man had said farewell to his wife Flavia Augustina, who expired aged thirty-nine years, seven months and eleven days, his son Saenius Augustinus who had survived only one year and three days, and a daughter whose name is lost but who lived for one year, nine months and five days. Flavia Augustina, like so many mothers of that time, had experienced the tragedy of losing two infant children. The tombstone, however, was not a bespoke piece. The family is depicted with the parents standing behind their children, but the latter figures are more appropriate to a son and daughter of around eight and six years respectively. It was clearly purchased ‘off the shelf’ and an appropriate inscription inserted in the blank space.

Not all soldiers were impressed by the prospect of retiring to a colony in the provinces. Some found they were not even allowed to. According to the mutineer Percennius, who had worked up the troops over their grievances in Pannonia after the death of Augustus in AD 14, there were still men serving after 30 or even 40 years. Even if such a man managed to get out of the army, Percennius said, he was liable to find himself being offered a parcel of land in ‘waterlogged swamps’ or on ‘uncultivated mountainsides’. This cannot have been entirely true. Inscriptions from all round the Empire show that retired legionaries could and did retire to colonies in Italy, or in pleasant locations out in the provinces. These provincial colonies were often in towns close to their former forts, or which had replaced the fort when the legion moved on. Not surprisingly the settled veterans often took up with local women, especially as once discharged they could contract a legally valid union that gave their wives and the children all the normal privileges that went with marriage to a Roman citizen. Tacitus describes the German inhabitants of the colony at Cologne, referring to how they had intermarried with the first colonists and become ‘allied’ with them.

One veteran who settled far from home was Gaius Julius Calenus. A veteran of Legio VI Victrix, based at York. He came from Lyon in Gaul but evidently decided not to return there when he was discharged, probably because he had a family in Britain. Julius Calenus settled in the colony at Lincoln, 80 miles (130 km) to the south and founded in the late first century AD, where he must have been given a grant of land. His daughter Julia Sempronia set up her father’s tombstone there. Lincoln’s modern name of course preserves the settlement’s Roman name Lindum Colonia. Gaius Cornelius Verus came from Tortona in Italy. By the time he was discharged from the army he was a legionary with Legio II Adiutrix, which was based in Budapest. He decided to settle in Colonia Ulpia Traiana Poetovio (Ptuj), a colony in Pannonia established by Trajan in 103, where he had been awarded a ‘double grant of land’, perhaps because his job in the legion already earned him double pay. His tombstone says that he was serving as clerk to the governor of the province. However, he did not live long enough to enjoy his retirement. He died at the age of fifty and was buried at Ptuj.

The trades and skills acquired in military service probably, and sometimes definitely, lay behind a veteran’s choice of post-army career. Vitalinus Felix, a veteran of Legio I Minervia, lived long enough to retire and chose to settle, not in or near the legion’s base in Bonn, but in Lyon in Gaul with his wife Julia Nice and their son Vitalinius Felicissimus. Described as a ‘wise and faithful man’, Vitalinus Felix set up in business as ‘a trader in the pottery craft’. He died aged fifty-eight years, five months and five days. His choice of trade is an interesting one. Traders in pottery (negotiatores cretarii, literally ‘traders of pots’) were often, as so many men involved in commercial enterprises were freedmen. Vitalinus Felix had perhaps learned to manufacture or deal with pottery while serving in the legion – the army had vast needs for ceramics. On the other hand, Lyon was a major Roman city and trading centre. It lies around 90 miles (143 km) from the massive red-slip samian-ware potteries of Lezoux, whose products dominated tableware in the Western Empire in the second century. Vitalinus Felix may therefore have been an entrepreneur who shipped local pottery to markets further afield.

Gaius Gentilius Victor definitely stuck with what he knew. After retirement from Legio XXII Primigenia he worked during the reign of Commodus in the late second century as a dealer in swords (negotatior gladiarius) at Mainz, the legion’s base.

Nothing else resembling either of these inscriptions is known, but it is certain that many other veterans built second careers. Julius Demetrius once served with Cohors III Augusta Thracum and settled in a village near the unit’s base at Sachare in Mesopotamia. He is recorded there in 227 as having purchased for 175 denarii a plot of land elsewhere in the area with fruit trees and 600 vine-stumps by a vineyard, perhaps both for pleasure and as a source of income. The transaction was witnessed by several serving soldiers. Another veteran had to act on behalf of the vendor, Otarnaeus, who was illiterate, illustrating how much better educated soldiers and ex-soldiers could be than the civilian population.

More often, veteran praetorians would return to their homes. This must have been even more likely to happen once praetorians were recruited from the whole army, as happened under Severus from 193. Sextus Quinctilius Seneca was a veteran of Cohors III Praetoria when he made a dedication to Jupiter on the island of Rab in Dalmatia (Croatia).44 Gaius Terentius Mercator, veteran of Cohors III Praetoria, expired at Como, where he was buried according to the instructions in his will.45 Gaius Carantius Verecundus, a veteran of Cohors VII Praetoria in Flavian times, was buried by his freedmen at Riati in Italy.

The Roman military veteran Nonius Datus continued to work as an engineer after his military service, attached to Legio III Augusta in North Africa. When the townsfolk of Saldae in the province of Mauretania Caesariensis got into difficulty with the tunnel they had been digging to bring a mountain water supply to their city – the two digging parties, which consisted of military personnel, had made a mistake in surveying the hill and ended up missing each other – Nonius Datus was called in to help them solve the problem. It was not at all surprising to find an old soldier stepping in like this; indeed he had to be called back several times to keep the project on track. Roman military veterans pop up all over the Roman Empire in numerous contexts that reflect the skills they had learned when in the army.

The unusually named Eltaominus had served as an architectus with Ala Vettonum, a cavalry unit sufficiently distinguished to have been awarded Roman citizenship in service. The Ala is attested at various locations in Britain, including Binchester where Eltaominus’ altar was found. Eltaominus described himself as an emeritus (‘veteran’) on a dedication to Fortuna Redux (‘the Home-Bringer’). He had perhaps been away on a trip and had returned to the fort, where he presumably lived in the vicus.

In the Fayum in Egypt in the early second century AD a veteran called Lucius Bellienus Gemellus made a living as a farmer in retirement. Thanks to the survival of some of his personal archive, a surprising amount is known about his everyday life. Gemellus was a networker who knew the value of keeping local officials on side, so he made sure to send them gifts. He also participated in religious ceremonies. On 6 November 110, for example, he wrote to an agent with instructions to ‘buy us some presents for the Isis festival for the persons we are accustomed to send [them] to, especially the strategoi’. Another document of 110, written to his son Sabinus, records that he wanted olives and fish sent to a man called Elouras who had recently been made deputy to the strategos Erasus, and cabbages sent to Erasus who was about to celebrate the festival of Harpocrates. These and other documents from the archive paint a picture of a veteran thoroughly involved with local life, managing it all almost as if he was still in the army with its love of bureaucracy and records.

Gemellus seems to have been happy, if busy, but a former soldier could all too easily turn into a disgruntled old man. Gaius Julius Apollinarius lived at Karanis in Egypt between 169 and 172 after his military service in Cohors I Apamenorum. He had established himself as a well-to-do landowner, buying and selling land there even while he was still in the army, as well as acquiring an unofficial wife. But in retirement he was furious that the five-year exemption from compulsory public services (such as acting as a tax collector) for veterans had been overturned when a demand came for him to perform those services after only two years. This was not even supposed to happen to the native population, or so the furious Apollinarius moaned; he expected the rules to be even more strictly observed when it came to someone like himself. In the year 172 he sent off his petition to the strategos, explaining that he wanted to be able to take care of his property ‘since I am an old man on my own’.

SIGNING ON AGAIN

Some soldiers were unable to resist the temptation to sign up again. When they did so they were called evocati Augusti, ‘men recalled to arms by the emperor’. Such men were absolutely essential to the Roman army’s ability to fulfil its duties. While he was governor of Germania Superior, Galba made as much use of veterans as he did of soldiers still in service. By training them all at the same pace he pushed them into such good condition that he was able to hold back any barbarian incursions.

Gaius Vedennius Moderatus came from Anzio in Italy. He served in Legio XVI Gallica for ten years, doing well enough to be rewarded with a transfer to Cohors VIIII Praetoria probably in 69. He retired having clocked up a further eight years’ service in the Guard, but was promptly recalled to sign on for another 23 years under Vespasian and Domitian as a reservist architectus armamentarius with specialist artillery skills, probably because he was regarded as indispensable. No doubt Moderatus had acquired his invaluable experience with artillery after Legio XVI Gallica threw in its lot with Vitellius during the Civil War, so his transfer to the Praetorian Guard may have come about as a result of Vitellius’ policy of allowing his soldiers to choose which section of the army they wished to serve in. Soldiers who so wished were allowed to join the Guard ‘however worthless’ they were, but in Moderatus’ case he may already have proved his worth.

Moderatus’ military service thus extended to over 40 years, during which time he was decorated by both Vespasian and Domitian. He must have been well into his sixties when he died, early in the reign of Trajan. His tombstone advertises his special skills by, for example, depicting on one side a ballista. Moderatus was unusual. He stayed with the Guard for an exceptionally long time and presumably reached the point where the idea of leaving was beyond his ability to contemplate. As an interesting aside, a bronze plate has been found from a catapult used in one or other of the battles at Bedriacum in 69. The embossed plate was fitted to the front of the catapult with a hole for the bolt to pass through. Above the hole is the name of the legion, in this case Legio IIII Macedonica, while on either side are a pair of military standards bearing bulls, the legion’s emblem, and the names of the consuls for 45 in the reign of Claudius, the governor of Germania Superior, Gaius Vibius Rufinus, and the centurion Gaius Horatius, who was princeps praetorii, ‘centurion in charge of the headquarters’. The veteran catapult was thus well over two decades old at the time of the battle and was still in service.

Remaining in the army was potentially dangerous. Aulus Sentius, from Arrezo, was a veteran of Legio XI sometime in the first century AD. He ‘was killed in the territory of the Varvarini in a small field by the river Titus at Long Rock [in Dalmatia]’, evidently while still serving in the front line.

Veterans of course had skills that could be useful in other contexts than the battlefield. When Otho wanted his dead rival Galba’s praetorian prefect Cornelius Laco killed – the hapless Laco had been under the impression that he was to be exiled to an island – he commissioned a loyal veteran to go and murder him. Nymphidius Lupus on the other hand was used in a more positive way. He rose to the heights of being primus pilus in Legio III Gallica, where he knew Pliny the Younger around the year 81 when the latter was a military tribune in the same legion. ‘From then on I began to develop a special regard for his friendship’, wrote Pliny to Trajan, and the two evidently stayed on excellent terms thereafter. When Pliny became governor of Bithynia he wrote to Lupus and asked him to give up his retirement and join him as a sort of adviser. When Lupus agreed, Pliny wrote to Trajan to ask for promotion for Lupus’ son by way of repayment.

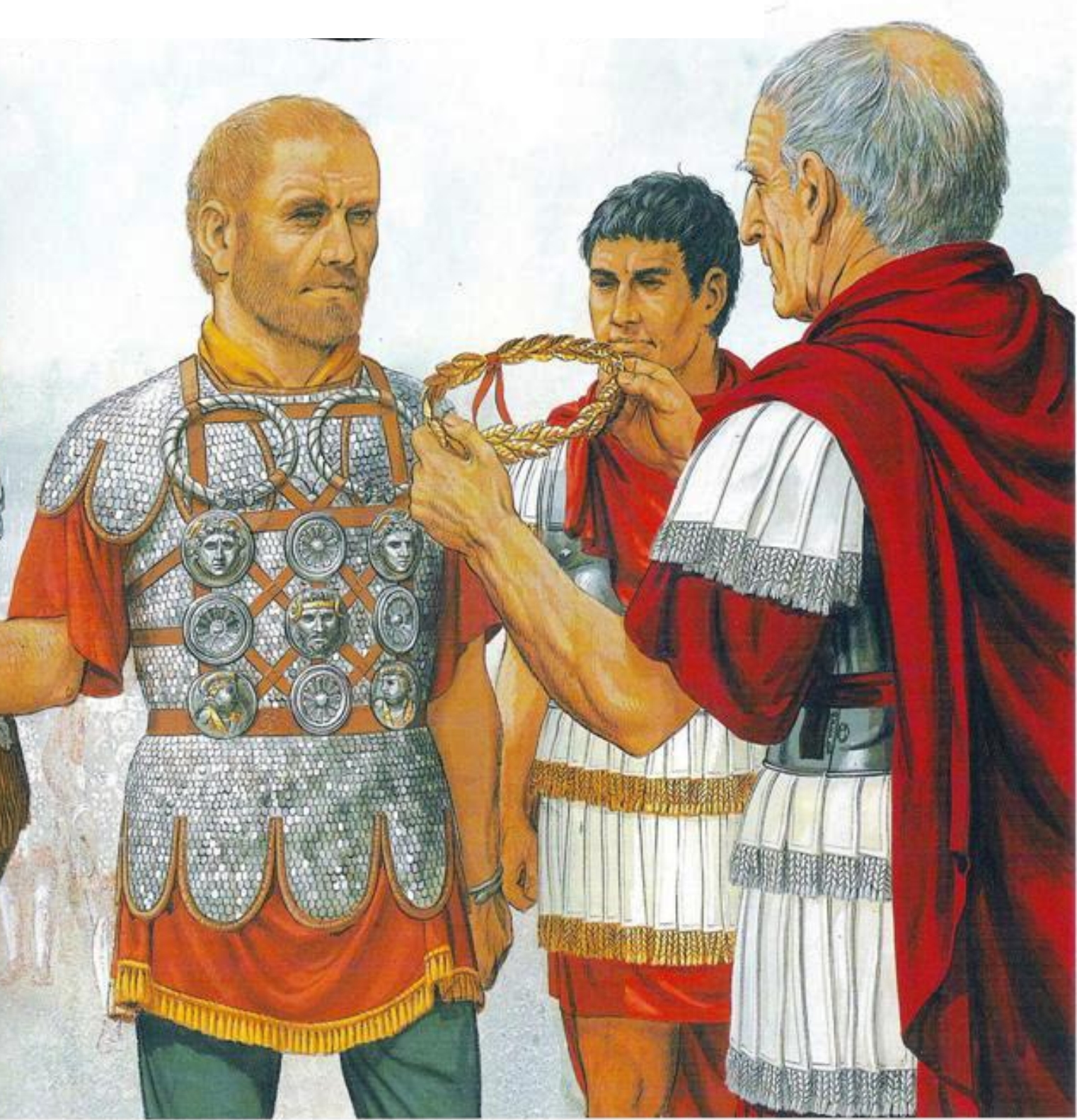

PROMOTION BY HEROISM

Tiberius Claudius Maximus did well during his time in the army in the late first and early second century, but apparently not so well that anyone else could be bothered to record the fact. Therefore he commemorated himself. As a veteran he commissioned an inscription found at Philippi that documented his time in Legio VII Claudia. Having been a quaestor equitum, a title which is otherwise unknown and probably meant he was in charge of the treasury of the legion’s cavalry, he then served in the legate’s mounted bodyguard before being made a vexillarius of the cavalry in the legion. Decorated for his feats in Domitian’s Dacian War, he fought in Trajan’s Dacian and Parthian wars where he served as a duplicarius in Ala II Pannoniorum before being promoted to decurio for – so he claimed – capturing the Dacian king Decebalus and bringing his head to Trajan. The claim is spurious, because Decebalus had already taken his own life; but it is plausible that Claudius Maximus found the body, severed the head and took it to the emperor. He continued to serve after his official term of service was up, and finally received his honourable discharge as a voluntarius in the army of Mesopotamia under Terentius Scaurianus.

BAD LUCK

Not all soldiers retired from the army to enjoy life. At some point before the mid-first century BC one veteran, whose name is unknown, came home to find that his father had been falsely told that he had died. The father had named other heirs in his will as a result and had himself then expired. The soldier therefore found he had nothing, while his father’s friends, who had been the beneficiaries, shut him out in spite of the personal sacrifice he had made fighting for the Roman state. Forced to pursue a legal campaign in the forum at Rome, he eventually won his case by a unanimous vote and was restored to his family estate.

Another veteran whose retirement went disastrously wrong was Claudius Pacatus. Pacatus had risen to the ranks of the centurionate by the time he was discharged in the late first century. Unfortunately, it was discovered in 93 that he was a slave and had evidently managed to conceal the fact when he enlisted. Domitian, acting in his capacity as censor, ordered that Pacatus be returned to his former master.

Even those who made it into retirement did not necessarily live long enough to make the most of their freedom from duty. Gaius Julius Decuminus, who served with Legio II Augusta at Caerleon, died when he was only forty-five. He was by then a veteran of the legion and had remained close to its base but evidently did not live long to enjoy the privileges of his status. His anonymous wife was left to organize his funeral.

Wherever a Roman soldier came from, and wherever he served, the experience stayed with him for life. For some men it proved impossible to let the army go, especially if retirement meant unfamiliarity and a loss of contact with old comrades. Normally, veterans were settled in colonies drawn from their old units. In 61 under Nero, however, the colonies at Tarento and Anzio in Italy were peopled by veterans drawn randomly from bases all over the Empire. The idea was that they would make good a decline in the local populations; but the scheme fell flat when most of the veterans, faced with other men they had never seen before, slunk off back to the frontier provinces where they had served. Some even abandoned wives and children in the colonies, preferring a retirement near their old bases where the sight, sound and smell of the Roman army made them feel at home. Once a soldier, always a soldier.