Popes, Cardinals and War: The Military Church in Renaissance and Early Modern Europe by D.S. Chambers (Author)

‘Blessed are the peacemakers.’ But blessed, too, have been the warmongers throughout the Christian centuries. Among the many aspects of this paradox a particular problem arises: how far could papal authority and the clerical hierarchy go in supporting or even committing acts of war in defence of the Church? The question has never been resolved with precision. St Ambrose (ca.340–97) proclaimed that – unlike Old Testament leaders, such as Joshua or David – Christian clerics should refrain from force: ‘I cannot surrender the church, but I must not fight’ ‘pugnare non debeo’; ‘Against weapons, soldiers, the Goths, tears are my arms, these are the defences of a priest.’ These precepts set the canonical line, but a fine distinction in culpability came to be admitted between inflicting violence directly and inciting others to acts of violence and bloodshed. It remained a matter of serious concern throughout the Middle Ages and beyond: how was the necessary defence of the Church to be defined and limited? Could the clergy, the officers of the Church, in conscience wholly avoid being involved in homicidal physical conflict, at least in self-defence?

In practice, when acute physical dangers threatened the Church, and its Roman power base in particular, active response must have seemed a matter of duty. The site of Rome, halfway down the ‘leg’ of Italy, was extremely vulnerable once the huge resources, military and naval strength, and well-maintained road system of the empire had gone. Successive hordes of invaders attacked or threatened the Roman bishopric’s sanctuaries and scattered estates, as well as overrunning other provinces of Italy. In the summer of 452 Pope Leo I reputedly stopped the Huns in their tracks only thanks to a miraculous if terrifying overflight of St Peter and St Paul, but Pope Gregory the Great (590–604) confronted the Lombards with military leadership. He exhorted his military captains to strive for glory, and provisioned and directed troops in defence of Rome. Two centuries later the recurrent invaders were Muslim Arabs or Moors from North Africa. Leo IV (pope 847–55) accompanied the Roman army that fought victoriously against Muslim pirates at the mouth of the Tiber, and was responsible for building fortified walls to protect the Borgo Leonino, the district near St Peter’s. John VIII (pope 872–82) in 877 commanded a galley in a joint naval campaign with Amalfitan and Greek forces against the Muslims. Maybe the scale of the victory was exaggerated, but the nineteenth-century historian Ferdinand Gregorovius felt justified in writing ‘this is the first time in history that a Pope made war as an admiral’. He quoted a letter allegedly from the Pope himself, claiming that ‘eighteen ships were captured, many Saracens were slain and almost 600 slaves liberated’. In 915 John X (pope 914–28) was present at another victory against Muslims on the river Garigliano in 915, and wrote to the Archbishop of Cologne boasting that he had bared his own chest to the enemy (‘se ipsum corpusque suum opponendo’) and twice joined battle. It is arguable that the papal resistance was largely responsible for saving the mainland of Italy from the Muslim domination that befell Sicily and much of Spain.

A very different challenge was presented by the northern ascendancy of the Frankish monarchy in the eight and ninth centuries. Its professed role was to protect the papacy, and this included large-scale ‘donations’ of territory in Italy, by Pepin (754), Charlemagne (774) and Louis the Pious (817). These confirmed at least some of the items in the forged ‘donation’ of Constantine, according to which the recently converted Emperor Constantine I, who moved his capital to Byzantium (henceforth Constantinople) in 330, transferred to the Pope extensive rights and possessions in the west. Not until the ninth century, however, did the boundaries of these claims begin to become at all geographically precise, including much of Umbria and extending north of the Appenines to parts of Emilia.

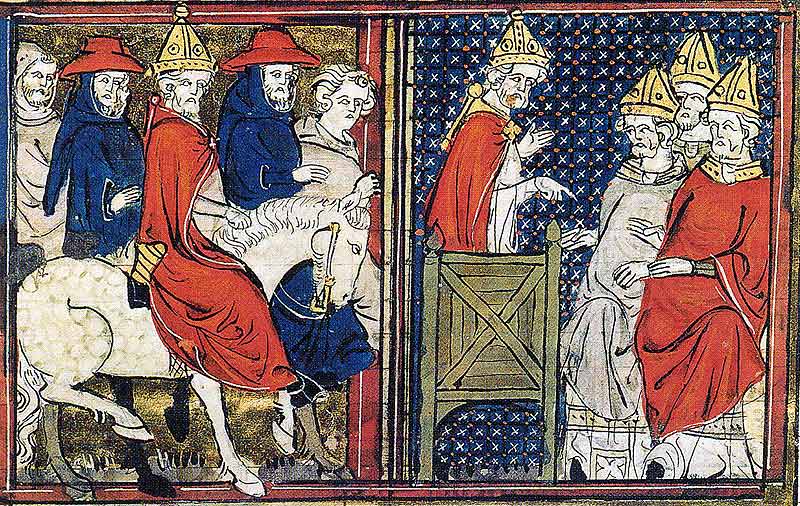

The Frankish kings’ protective, military role was graphically expressed by Charlemagne in a famous letter congratulating Leo III (pope 795–816) on his accession. In this he declared that, while his own task was to defend the Church by arms, the Pope would simply need to raise his arms to God, like Moses did to ensure victory over the Amalikites (Exodus XVII, 8–13). The other side of the bargain was that the Pope should perform coronation of his protector as emperor, the revived title duly conferred on Charlemagne in Rome on Christmas Day 800. As the imperial office also carried an aura of divinity, this protective role would eventually lead to trouble, a challenge over primacy of jurisdiction, but meanwhile it helped to preserve the papacy’s dignity. Another Germanic dynasty subsequently rescued it from the scandalous if obscure confusion that prevailed in Rome during the first half of the tenth century. During that period the local nobility, and even two unscrupulous matriarchs, Theodora and her daughter Marozia, determined the appointment and even perhaps the deposition of several popes. After 960, however, three Saxon emperors, all named Otto, began to repair the situation. Early in 962 Otto I was crowned by Marozia’s son, John XII (pope since 957), who had appealed for his protection, but in December 962 John was deposed by Otto. According to Liudprand, Bishop of Cremona, who acted as Otto’s interpreter and is therefore fairly credible as a source, this was in response to collective denunciations by senior Roman clergy. Among the alleged offences of John XII were fornication, drunkenness, arson and playing at dice, but a special emphasis seems to have been placed on publicly bearing arms. Ultimately he had turned against his imperial protector and advanced with troops against Otto’s army ‘equipped with shield, sword, helmet and cuirass’. Otto allegedly declared, ‘There are as many witnesses to that as there are fighting men in our army.’

Most successful in sharing or dominating the papacy’s authority was Otto I’s grandson Otto III. He resided in Rome once he had come of age in 996 and oversaw the appointments of his cousin Bruno of Carinthia (Gregory V, pope 996–99), who crowned him emperor, and the learned Gerbert of Aurillac (Silvester II, pope 999–1003). Both Otto I and Otto III also issued new ‘donations’, confirming the Frankish concessions of papal title to territories formerly occupied by Byzantine Greeks and Lombards. Much of central Italy, including Umbria, southern Tuscany and lands bordering the Adriatic roughly from the region of Ravenna down to Ascoli, were redefined as potential lands of St Peter. Only ‘potential’, of course, because these claims under ‘donation’ would be hard to realise and enforce; centuries of effort, with many setbacks, lay ahead. After a relapse under local political forces in the early eleventh century, the papacy again came to be protected by a German royal dynasty. From 1046 to 1055, under the Salian Henry III, a succession of reputable popes were appointed, and to one of these, Victor II, Henry conceded rule over the March of Ancona, but seemingly as an imperial vassal. For popes to have to admit the superiority or semi-parity of the emperor’s office was a hard price to pay for security.

In the course of the eleventh century lofty ideas were advanced concerning both the nature of papal authority and – as an inevitable aspect of this – ecclesiastical sanctions of warfare. There were of course earlier pronouncements on the superior nature of papal power. Gelasius I (pope 492–96) is credited with introducing the idea of the Church as a principality set above all earthly princes and the pope as the vicar not only of St Peter but of Christ himself. Nicholas I (pope 858–67) pronounced that the papacy was the greater of the two lights set over the earth, that popes were princes over the whole world, and only with their sanction could the emperor use the sword; he even quoted St Peter’s use of the physical sword against Malchus. But it was not until the eleventh and twelfth centuries that scholars concerned with establishing the ‘canon law’ of the Church – pronouncements, rulings and precedents governing Church affairs laid down by successive popes and jurists – built up systematically, with the support of theologians, the ‘hierocratic’ theory of superior and universal papal power, including the power to depose unworthy rulers.

These ideas, however strong in their implications for future wars, need not concern us at this point so much as two practical measures designed to ensure more effective papal authority, both of them the achievements of Nicholas II (pope 1059–61). One was the decree that laid down regular procedure in papal elections: that popes could only be elected by the ‘cardinal’ bishops, priests and deacons of Rome. As well as this constitutional provision aimed at stabilising the papal monarchy – though it failed for centuries to avert counter-elections of ‘antipopes’ – in the same year 1059 a momentous step was taken to bring the southern half of Italy and Sicily under the legal lordship of the papacy. This was the grant of conditional rulership made to the Normans Robert Guiscard and Robert of Capua, who had previously been regarded as the most troublesome and threatening of intruders in that region. The Treaty of Melfi created them dukes ‘by the grace of God and St Peter’, with a promise of the lordship of Sicily, conditional on its recapture from the Muslims. It decisively overruled or disregarded any surviving claims of Greeks, Lombards, Muslims or other de facto occupiers, and the inclusion of Sicily seems to have depended on the donation of Constantine rather than any later, more valid concessions. This turning of southern Italy into a papal fief, with obligations upon its ruler to owe the Pope military support, would have enormous consequences in the future.

Specifically on the issue of war, first, there was also a legalistic dimension that developed in the eleventh century. One of the earliest specialists in canon law, Burchard of Worms (ca.965–1025), insisted ‘the clergy cannot fight for both God and the World’, but later canonists accepted that the problem was more complicated than this. Second, there was also a spiritual dimension, investing war – in certain circumstances – with a positive value. This was an aspect of the monastically inspired reform movement in the Church. Leo IX (pope 1049–54), Bruno, the former Archbishop of Toul, was one of a group of serious reformers in Lorraine who combined austere religious standards with a warrior mentality, as did his colleague Wazo, Bishop of Liège, who was acclaimed by his biographer as a ‘Judas Maccabeus’ in his military exploits, praised for defending Liège and destroying the castles of his opponents. As archbishop Bruno had led a force in support of Emperor Henry III. As pope he waged war against his deposed predecessor Benedict IX and his partisans in 1049–50 and personally commanded an army of Swabians against the Normans in June 1053, suffering defeat at the Battle of Civitate, the disaster that made clear that the only way forward was to adopt the Normans as allies rather than enemies. Among Leo IX’s recorded declarations was the precept ‘Those who do not fear spiritual sanction should be smitten by the sword’, though it was intended mainly against bandits and pagans.

Penetrated by both monastic reforming zeal and by canon law experts who insisted on a universal, ultimate pontifical authority over the emperor and all other secular powers, the later eleventh-century papacy was almost bound to accept that force could be sanctioned, that war and bloodshed in the right cause could even be sacred. Matters reached a head in the 1070s, with recurrent conflict between the Franconian Henry IV, king, and the emperor-elect since 1056 and the former monk Hildebrand as Gregory VII (pope 1073–85). Even before he became pope, Hildebrand had been involved in the use of force. He may have served with Leo IX; certainly he was associated with Alexander II (Anselm I of Lucca) in 1061–63. He had been largely responsible for bringing the Normans into papal service, and for employing independent military figures such as Godfrey of Lorraine. They enabled Alexander to overcome the anti-pope Cadalus, Bishop of Parma (‘Honorius II’), who for a while had controlled Rome. Hildebrand, unlike so many of the medieval popes, was not born into the nobility or warrior caste, but scientific tests of his bones have shown at least that he was sturdily built and used to riding a horse.

Soon after becoming pope, Gregory VII issued direct orders to the papacy’s mercenary forces, notably the Normans under Robert Guiscard. On 7 December 1074 he wrote to Henry IV, claiming that thousands of volunteers were calling upon him to combine the roles of ‘military commander and pontiff’ (‘si me possunt pro duce ac pontifice habere’) and lead in person an army to aid eastern Christians against the Seljuk Turks.

Gregory’s conflict with Henry IV was at first a war of words rather than of arms. It was partly legalistic, over investiture to higher Church appointments and the need for clerical reforms, but even more over incompatible temperaments and claims of superior authority. The conflict blew hot and cold; in 1075, until the autumn, Gregory seemed on the point of agreeing to crown Henry emperor, but the following year he was excommunicated. Nevertheless in January 1077 he presented himself at Canossa as a penitent. In 1080 Gregory excommunicated Henry IV for the second time, whereupon the pro-imperial bishops at the Synod of Brixen elected Guibert, Archbishop of Ravenna, as anti-pope. Then Gregory announced that ‘with the cooler weather in September’ he would mount a military expedition against Ravenna to evict Guibert. He also had in mind a campaign to punish Alfonso II of Castile for his misdeeds, threatening him not just metaphorically: ‘We shall be forced to unsheathe over you the sword of St Peter.’ While it would be hard to prove that Gregory VII ever wielded a material sword, and his frequent pronouncements invoking ‘soldiers of Christ’ or ‘the war of Christ’ may sometimes have been metaphorical rather than literal, it is easy to see how his enemies – those serving Henry IV or Guibert of Ravenna – could present his combative character as bellicose on an almost satanic scale. ‘What Christian ever caused so many wars or killed so many men?’ wrote Guy of Ferrara, who insisted that Hildebrand had had a passion for arms since boyhood, and later on led a private army. Guibert, who wrote a biographical tract denouncing Hildebrand, made similar allegations. Such criticism carried on where the militant reformer and preacher Peter Damiani (1007–72) had left off; although in many respects Damiani’s views on what was wrong with the Church were compatible with Hildebrand’s, he had insisted that ecclesiastical warfare was unacceptable: Christ had ordered St Peter to put up his sword; ‘Holy men should not kill heretics and heathen…never should one take up the sword for the faith.’

Further justifications of military force initiated and directed by popes had to be devised. Gregory’s adviser and vicar in Lombardy from 1081 to 1085, Anselm II, Bishop of Lucca, made a collection of canon law precedents at his request. In this compilation Anselm proposed that the Church could lawfully exert punitive justice or physical coercion; indeed, that such a proper use of force was even a form of charity. ‘The wounds of a friend are better than the kisses of an enemy,’ he declared, and – echoing St Augustine – ‘It is better to love with severity than to beguile with mildness.’ He invoked the Old Testament parallel, arguing that Moses did nothing cruel when at the Lord’s command he slew certain men, perhaps alluding to the punitive slaughter authorised after the worship of the Golden Calf (Exodus XXXIII, 27–8) or to the earlier battle of Israel against the Amalekites, when the fortunes of war depended on the effort of Moses’s keeping his arms in the air (the episode Charlemagne had quoted to Leo III). Anselm does not go so far as to recommend that popes and other clergy should personally inflict violence on erring Christians, but he allows that they could mastermind it; the rules might be even more relaxed in wars against non-Christians, including lapsed and excommunicated former members of the Catholic Church.

Few of Gregory VII’s successors could equal that extraordinary pope’s remorseless energy, but on their part there was no renouncing of coercion by force. Even Paschal II (pope 1099–1118), a sick and elderly monk, who submitted to the humiliation of imprisonment by the Emperor Henry V in 1111, spent much of his pontificate going from siege to siege in the region of Rome. In the year of his death he supervised the mounting of ‘war machines’ at Castel Sant’Angelo to overcome rebels occupying St Peter’s. Innocent II (1130–43) was engaged in war with a rival elected soon after himself – possibly by a larger number of the cardinals – who took the name Anacletus and for a while even controlled Rome itself. Both of them found strong backers. Anacletus persuaded the German king Lothar to bring military force against his rival; Innocent obtained the support of Roger II, the Norman ruler of Sicily. In July 1139 Innocent definitely had the worst of it when an army led by himself was ambushed at Galluccio, near the river Garigliano between Rome and Naples. He was taken prisoner and had to concede to Roger investiture as king of Sicily, which Anacletus had previously bestowed on him. This was a considerable upgrading of the title ‘Apostolic Legate’, which had been conferred on Roger’s father and namesake in 1098 in recognition of the successful reconquest of Sicily from the Muslims. The grant of kingship was the culmination or reaffirmation of the policy intended to ensure a strong and loyal military defence for the papacy in the south. As a favoured relationship it had not worked altogether smoothly. One of its lowest points was Robert Guiscard’s delay in coming to the help of Gregory VII in 1084, when he delivered Rome from its long siege by Henry IV, but caused a bloodbath; another low point was the war in the 1130s mentioned above. Yet another papal defeat by Norman forces, in spite of the concession of kingship to Roger II, befell Adrian IV at Benevento in 1156. In all these military conflicts it cannot be proved that Paschal II, Innocent II, Anacletus or Adrian IV engaged physically in fighting, but in each case they accompanied armies and appear to have directed – or misdirected – field operations.

A formidable challenge arose in the middle of the twelfth century on the part of the empire, the very authority that was supposedly ‘protecting’ the papacy. In the hands of Frederick I ‘Barbarossa’, of the Swabian Staufer or Staufen family – generally but incorrectly called Hohenstaufen – the empire or its lawyers advanced its own claims to government of cities and lands in northern Italy, including the city of Rome, despite local civic aspirations. The English cardinal Breakspear, elected as Adrian IV (pope 1154–59), duly crowned Frederick in 1155, but his safe arrival at St Peter’s had depended on his relative, Cardinal Octavian, securing it with armed force. The imperial decrees issued at Roncaglia, near Piacenza, in 1158 made clear that Frederick had no greater respect for the judicial, fiscal and territorial claims of the papacy than he had for civic autonomy. Adrian IV, under whose rule there had been a certain advance in papal control of central Italian castles and towns, protested vehemently to the emperor. In practice, however, in his three invasions of Italy Frederick was more concerned with Lombardy and its rapidly growing and de facto independent mercantile cities, above all Milan, which as punishment for its defiance he devastated in 1162. Without seeking direct military confrontation, the astute Sienese jurist Cardinal Rolando Bandinelli, elected as Alexander III (pope 1159–81), gave financial and moral support to the Lombard cities. He had meanwhile to contend with a series of anti-popes elected by proimperial cardinals. After the Lombard League’s famous victory against Frederick at Legnano in 1174 Alexander was able to play the role of mediator and peacemaker. Much of central Italy nevertheless was subjected in his time to imperial, not papal, jurisdiction and taxation, under the direction of men such as Christian of Mainz, whose administrative capital was Viterbo, and Conrad of Urslingen, who in 1177 became imperial Duke of Spoleto. In 1164 Frederick Barbarossa had even ordered Christian to move with an army to help install his antipope in Rome. The reversal of this imperial heyday had to wait until after the deaths of Barbarossa (drowned on crusade in 1190) and his son Henry VI in 1197.