When Burgoyne’s army piled its arms on the surrender field at Saratoga, the event could have been rightly celebrated by the Americans as their greatest victory of the war. Some thirty months later, and hundreds of miles to the south, the British were entitled to claim their greatest success of the war. On 12 May 1780 General Benjamin Lincoln, the same Lincoln who commanded a wing of Gates’s army at Saratoga, surrendered the city of Charleston, South Carolina, and its garrison to Sir Henry Clinton. The loss of the South’s largest city and seaport was serious enough, but what went with it was staggering—one of the major catastrophes suffered by the colonials during the whole war. The forty-four-day siege yielded to the British over 5,000 prisoners of war, 6,000 muskets, 391 cannon, and immense stores of ammunition and other supplies. The cost to the British: 76 killed and 189 wounded.

What had brought Sir Henry Clinton to Charleston and this surprising success? Clinton had succeeded Howe as commander in chief of His Majesty’s forces in America in March 1778. He assumed actual command in May upon Howe’s departure. After undergoing several setbacks in the North, Clinton found himself on the strategic defensive, though he had never given up his grand plan to take the offensive in the South. When the combined forces of American and French failed to take Savannah by siege and storm, French Admiral d’Estaing reembarked his troops and sailed back to France in October 1779. The small American force withdrew to Charleston, amid hard feelings toward the French by the Patriots and no end of jubilation among southern Loyalists, who renewed their call for a British invasion of the Carolinas.

All this good news, along with the assurance of a firm British hold on Georgia, led Clinton to decide that the time was right for undertaking his southern campaign. His plan was a bold one, and clear enough on the map. His first objective was Charleston, and following its seizure he would make that seaport his base of operations in the South. From then on it would be mainly a land campaign, with its major thrust northward across South Carolina, through North Carolina, and up into eastern Virginia. A major purpose behind all the thrusting was that steadfast aspiration that so influenced British strategic planning throughout the war: the belief that the Loyalists would come forward to reinforce British regular forces in large numbers. That illusion, as Page Smith saw it, was “that the great majority of the people of the South were loyal to the Crown and would with a little encouragement, avow that loyalty and take up arms, if necessary, to vindicate it” (A New Age Now Begins). When British commanders became disillusioned enough to see the real world, it was obvious that the Crown’s law and order could be maintained only in the areas occupied by His Majesty’s forces. When British troops passed on or were withdrawn from an area, either that quarter reverted to Patriot control or guerrilla warfare broke out anew.

Sir Henry Clinton was able to carry out the initial phase of his southern offensive without a hitch. Accompanied by Cornwallis as his second in command, Clinton sailed from New York in December 1779 with a fleet of ninety transports carrying 8,500 troops. In spite of a near-disastrous storm—the fleet was dispersed over a great expanse of the Atlantic for nearly a month and lost one transport full of Hessians, which was driven clear across the ocean to the English coast—the ships were finally reassembled and repaired at Savannah. Clinton then sailed for Charleston and began land operations in mid-February 1780. Although the operation was conducted at such a snail’s pace that the city was actually under siege only by the end of March, on 12 May Charleston was surrendered to Clinton, at tremendous cost to the Patriot cause in the South.

Clinton’s next step was the subjection of large interior regions of the Carolinas. His method was, insofar as practicable, to employ sizable detachments of Tories to do the job. Those operations resulted in raising Tory hopes and recruits, but also served to enflame what Christopher Ward describes as no less than “a civil war within the war against England” that was “marked by bitterness, violence and malevolence such as only civil wars can engender” (The War of the Revolution). The effects of the civil war on the operations of regular forces will be seen presently.

By the end of May Clinton was satisfied that things were going well enough for him to turn over operational control to Cornwallis. He sailed for New York on 5 June, leaving Cornwallis with some 8,300 men to carry on. Clinton’s concept of carrying on was to hold on to Georgia, South Carolina, and New York, and not to venture further in the immediate future. Cornwallis, however, had ideas of his own. He was to make his own broad interpretation of offensive operations that “did not jeopardize his primary mission of holding the large region of Georgia and South Carolina left . . . in British control when Clinton ventured to New York” (Boatner, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution). In effect, Cornwallis was going to embrace the old maxim that an offense is also the best defense. He envisioned, in fact, that an invasion of North Carolina would rally enough Loyalists to his banner so that he could eventually carry his offensive into Virginia, where he could link up with British forces from the North.

Cornwallis’s first moves to implement his own strategy included securing the subdued regions of Georgia and South Carolina by strengthening the critical posts at Savannah, Augusta, and Ninety-Six. Leaving his main force at Charleston, he then established a forward base at Camden, with outposts as far out as Georgetown, Cheraw, Hanging Rock, and Rocky Mount. Thus the solidly held territory of South Carolina was ringed by posts extending from Savannah in the south, northward through Augusta and Ninety-Six, and northeastward to Cheraw. The forward base at Camden was held by Lord Rawdon with 2,500 British regulars and Tory units.

The area to be secured was immense, comprising some fifteen thousand square miles, yet it had been subdued and occupied with ease. After the fall of Charleston only one Continental regiment remained in South Carolina, and what happened as it retreated northward clearly marked the end of Patriot resistance in South Carolina.

In mid-May 1780 Colonel Abraham Buford had marched his regiment, the 3rd Virginia Continentals, within forty miles of Charleston when he received news of the surrender; he then got orders to retreat to Hillsboro, North Carolina. Cornwallis dispatched Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton in pursuit. With a task force of 270 men, Tarleton caught up with Buford’s rear guard on the twenty-ninth at a place called Waxhaws, about ten miles east of present-day Lancaster, S.C. The American commander deployed into line on open ground, and his officers ordered their men to hold their fire until the charging cavalry came within ten yards of their line. The Continentals’ single volley was too late to break the momentum of Tarleton’s charge. The American line was shattered, and simultaneously the Tory cavalry swept around both flanks. The Continentals were encircled and soon became a helpless mass, most men throwing down their arms. Buford had Ensign Cruit raise a white flag; when Tarleton himself charged at the flag, his horse was killed. Seeing him downed, a fury swept through his troopers with the word that their leader had been shot down in front of a flag of truce. Tarleton could not or would not hold back his men. They were out of control, sabering right and left, ignoring any cries for quarter. In moments the Tory infantry of the legion were into the Americans with their bayonets. The Americans by now were completely helpless, since they had grounded their muskets when the white flag was raised. In Robert Bass’s version of the affair, “the infantrymen continued to sweep over the ground, plunging their bayonets into any living American. Where several had fallen together, they used their bayonets to untangle them, in order to finish off those on the bottom” (The Green Dragoon).

In this massacre was born the American battle cry of “Tarleton’s quarter!” The “Waxhaws massacre” and “Tarleton’s quarter” flamed across the Carolinas and Georgia to become household words, and Tarleton became the hated symbol of the Crown and Tory oppression, and henceforth was known as Bloody Tarleton.

American casualties were 113 killed and 203 prisoners, but 150 of those were too badly wounded to be moved. Buford escaped on horseback, losing all six pieces of his artillery and his entire supply train. Tarleton counted his casualties at 19 killed or wounded and a loss of 31 horses. Buford’s losses, however, became more symbolic than material; they symbolized the end of organized Patriot military power in South Carolina.

The Waxhaws affair also signaled the spread of civil War. Although there were too many skirmishes to recount, at least four actions took place after Waxhaws that could be called battles. They were notable not only for blood and bitterness but further for the absence of British regular troops.

On 20 June 400 Patriots under Colonel Francis Locke attacked some 700 Tories at Ramsour’s Mill in North Carolina. Each side lost about 150 men, losses which speak clearly for the fierceness of the encounter.

At Williamson’s Plantation on 12 July a hastily organized band of Patriots surprised a Tory raiding party by attacking its camp at dawn. Out of 115 Tories in the camp only 24 escaped; of the remainder, 30 to 40 were killed and 50 wounded. The attacking Patriots lost one man killed out of about 250 who actually made the attack.

The victory at Williamson’s Plantation encouraged many of the rebels to rally to the side of famed Thomas Sumter, the “Carolina Gamecock,” who was building up a force in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. Sumter decided to move against the fortified post at Rocky Mount, South Carolina, held by the Tory Lieutenant Colonel Turnbull with some 150 New York Volunteers and a detachment of South Carolina Tories. Turnbull had been warned of Sumter’s approach and was prepared. Three successive assaults were beaten back by the heavy fire of the defenders. After unsuccessful attempts to burn out the Tories, Sumter had to call it quits and withdraw to Land’s Ford on the Catawba River. Losses were equally light on both sides, each losing about fourteen killed or wounded.

Sumter had not earned the title of Gamecock by sitting around camp fires; four days after Rocky Mount, he left Land’s Ford to attack the heavily garrisoned outpost at Hanging Rock, about twelve miles east of Rocky Mount. Sumter had mustered 500 North Carolina militia and about 300 South Carolinians; all could be considered mounted infantry. Sumter divided his force into three columns, each with the mission of attacking one of the Tory camps. Their guides went astray, and all three divisions ended up on the front and flank of the North Carolinians on the Tory left. Sumter’s men drove on but were stopped by heavy fire from the legionaries and rangers of the enemy center. The Tory force commander, Major Garden, seeing his chance, took a detachment and fell upon Sumter’s flank. The surprised Americans rallied and, with amazing fierceness for militia, retaliated with such firepower that Tory casualties mounted to the point where Garden’s men fled or surrendered.

The main Tory camp and supply center were now wide open, and the triumphant victors went hog wild. Stores of rum were uncovered and gulped down, and while Sumter’s disorganized men were getting drunk and out of control, Garden formed some rallied men into a hollow square with two cannon on its corners and prepared to continue the fight. Garden was opposed by Major William Davie, a noted partisan leader. Davie had kept his “dragoons” under control and away from the looting. In the meantime Sumter had succeeded in drawing about 200 of his men from the looted camp. While so engaged he was threatened by two companies of legion cavalry who had come to join the fight. Davie led a charge against the new threat and drove the Tory cavalry out of sight. At this point, with the enemy square still standing fast, Sumter decided that further offensive action was out of the question and offered a general withdrawal. Outside of the fiasco in the looted camp, the battle had been fought with firmness and courage on both sides. The Tory losses were especially heavy: nearly 200 killed and wounded. The Patriots claimed to have suffered casualties of only 12 killed and 41 wounded, which is unlikely.

The Battle of Hanging Rock was the largest and last of the civil war actions after the fall of Charleston. Now, in early August 1780, new Patriot forces were entering the arena, forces not composed of partisans or irregulars.

When Sir Henry Clinton was making up his mind whether to stay on in Charleston or leave and turn the southern command over to Cornwallis, his decision was hastened by a bit of news: Comte de Rochambeau had left France for America carrying a large force of French troops bound for New England. The news prompted Sir Henry’s departure for New York on 5 June 1780. What was bad news for Clinton was, of course, good news for Congress and Washington. The latter had already sent a small force south under Major General Baron de Kalb in April 1780 to give “further succor to the Southern States.” De Kalb’s little army consisted of two brigades: the first comprising four regiments of Maryland Continentals; the second, three Maryland regiments and the Delaware regiment, all Continentals. The 1st Continental Artillery Regiment of eighteen guns marched in support. The force totaled 1,400 rank and file.

De Kalb was marching into North Carolina when he learned of Charleston’s surrender; the news had traveled with unaccountable slowness and reached de Kalb five weeks after the fact. Tough professional that he was, de Kalb refused to be disheartened. After several forward moves southward, he set up camp at Buffalo Ford, and from this base tried to raise reinforcements of militia, which should have become available. The hoped-for volunteers did not show up. Militia Major General Caswell, with a strong force of North Carolina militia, preferred to chase Tories elsewhere. Virginia militia led by Stevens and Porterfield also made themselves unavailable. While at Buffalo Ford, de Kalb got word of Horatio Gates’s appointment to command of the Southern Department. Washington’s man for the job had been Nathanael Greene; but Congress, with characteristic perversity, preferred the hero of Saratoga. The hero arrived at de Kalb’s new camp on Deep River on 25 July and assumed command of an army short of clothing as well as discipline. Through no fault of de Kalb’s, the army was exhausted and in bad need of all sorts of necessities, including rations and rum.

Gates immediately went on the offensive, his objective no less than the seizure of that tantalizing forward base of Cornwallis’s at Camden, with all its promise of life-restoring stores. Rejecting the route of advance proposed by de Kalb and his commanders, which would have taken the army through a relatively fertile region where most of the locals favored the Patriot cause, Gates ordered a more direct march through a desolate area dominated by swamps, pine barrens, and Tory sympathizers. Gates also turned down the request of Colonels William Washington and Anthony White for aid in recruiting horsemen, aid which would have been repaid handsomely if the two colonels had joined Gates’s army and furnished him with a reconnaissance and security force.

The army marched on 27 July, only two days after Gates’s arrival, and without the rations and rum which the soldiers had been promised. The hungry troops made 120 miles in two weeks, setting no records at an average of less than 9 miles a day. The promised rations never did catch up, so Gates promised them corn when they reached the Pee Dee River. “He was right, but the corn was still green, and soldiers who had been getting sick on green peaches now got sick on green corn instead” (Boatner, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution). Across the Pee Dee, Gates was joined on 3 August by Lieutenant Colonel Charles Porterfield with a small band of militia, and the yet-to-be-famous Colonel Francis Marion with twenty of his men.

Two days later Gates got a message from General Richard Caswell that he was about to attack a British outpost at Lynches Creek. When Caswell, with an estimated 2,100 men, advanced against the outpost, his “army” was thrown into disorder by a British surprise attack. The attack was actually a feint made by Lord Rawdon, commanding Cornwallis’s forces based on Camden. After his successful feint, Rawdon withdrew his detachment to Little Lynches Creek, where he occupied a strong position blocking the route to Camden.

On 6 August Gates was finally joined by Caswell, “adding 2,100 to his grand army, but greatly weakening it as the event proved” (Ward, War of the American Revolution). The combined forces moved forward toward Little Lynches Creek, bumping into Rawdon’s blocking force there on 11 August. De Kalb proposed to march up Little Lynches Creek at night, cross it, and turn the British out of their position while continuing to advance on Camden. Gates rejected the plan and instead tried a clumsy envelopment of the British left in broad daylight. Rawdon threw out a screening force of Tarleton’s legion and quietly pulled back to Camden.

Rawdon was met in Camden by Cornwallis on 13 August. What Cornwallis found was anything but cheering. His enemy’s estimated strength was 7,000, which Mark Boatner says was “an understandable error inasmuch as Gates himself was under the same misapprehension.” Cornwallis’s own strength was reported to him at 2,117 rank and file present for duty, with a dismaying 800 sick in the Camden field hospital. Of the effective 2,117, about 1,500 were regulars and the rest were dependable Tory units such as Tarleton’s legion, the Volunteers of Ireland, and two North Carolina regiments. Considering the estimated adverse odds of more than three to one, a lesser general would have fallen back on Charleston. Not so Charles Cornwallis; he would not abandon his sick in Camden. But even if they had not been there, he would still have taken the initiative and attacked his enemy. This he proceeded to do, and advanced northward to meet the Hero of Saratoga.

On 14 august 1780, the day after Cornwallis’s arrival at Camden, Gates’s army at Rugeley’s Mill received its last reinforcement, the 700 Virginia militia of General Edward Stevens. On that date Gates’s strength returns included de Kalb’s 900 Maryland and Delaware Continentals, Caswell’s 1,800 North Carolina militia, Armand’s command (formerly Pulaski’s legion) of 120, Porterfield’s 100 Virginia light infantry, about 70 volunteer cavalry, and 106 guns in Colonel Harrison’s Virginia artillery. In all, counting some “miscellaneous” attachments, Gates’s total would have come to about 4,100. Yet when Otho Williams, Gates’s adjutant general, showed him the morning report strength of 3,052 fit for duty, Gates, still believing he had over twice that many men, didn’t want to be confused with facts. He brushed off Williams with “there are enough for our purpose.”

With his “purpose” in mind, Gates, in a command conference on 15 August, read his operation order for an attack that night to his commanders. It would require them to maneuver over wooded sand hills and scattered swamps with an army of which over two-thirds were green militia and whose major elements had never operated together

Before the troops fell in for the march, a full ration of meat and corn meal was to be issued. There was, however, no rum, a customary stimulant before going into action. In its stead, Gates had a gill of molasses from the hospital supplies issued to each soldier. “The men ate voraciously of half-cooked meat and half-baked bread with a dessert of corn meal mush mixed with the molasses.” A sergeant-major described the results of the solution: “Instead of enlivening our spirits . . . it served to purge us . . . [and, Colonel Otho Williams added] the men were of necessity breaking the ranks all night and were certainly much debilitated before the action commenced in the morning” (Ward, War of the American Revolution).

With these unhappy auguries gates’s troops began their march as scheduled, at 10:00 P.M. on 15 August. The axis of advance was southward on the main road from Rugeley’s Mill to Camden. Colonel Armand’s horsemen preceded the advance, despite his warning to Gates that a cavalry unit was not right for the mission because it would be too noisy on the march and could not operate effectively in the woods. It was followed by Armstrong’s and Porterfield’s militia, who were followed by the advance guard of the Continentals. There was only starlight to see by; it was of no help to either the files slogging through sand and swamps or the column on the main road hemmed in by the dark pine woods.

About 2:30 A.M. on the sixteenth the march was brought to an abrupt halt by the sound of firing up ahead around Armand’s troops. They had run smack into the cavalry and infantry of Tarleton’s legion. Although the British advance party had only twenty cavalrymen and an equal number of legion infantry, Tarleton acted so quickly in attacking Armand’s troops that they wheeled away, spreading confusion among the Continentals’ advance guard. There was a firefight of sorts, which broke off in about fifteen minutes, since neither side had anything to gain by blazing away in the dark.

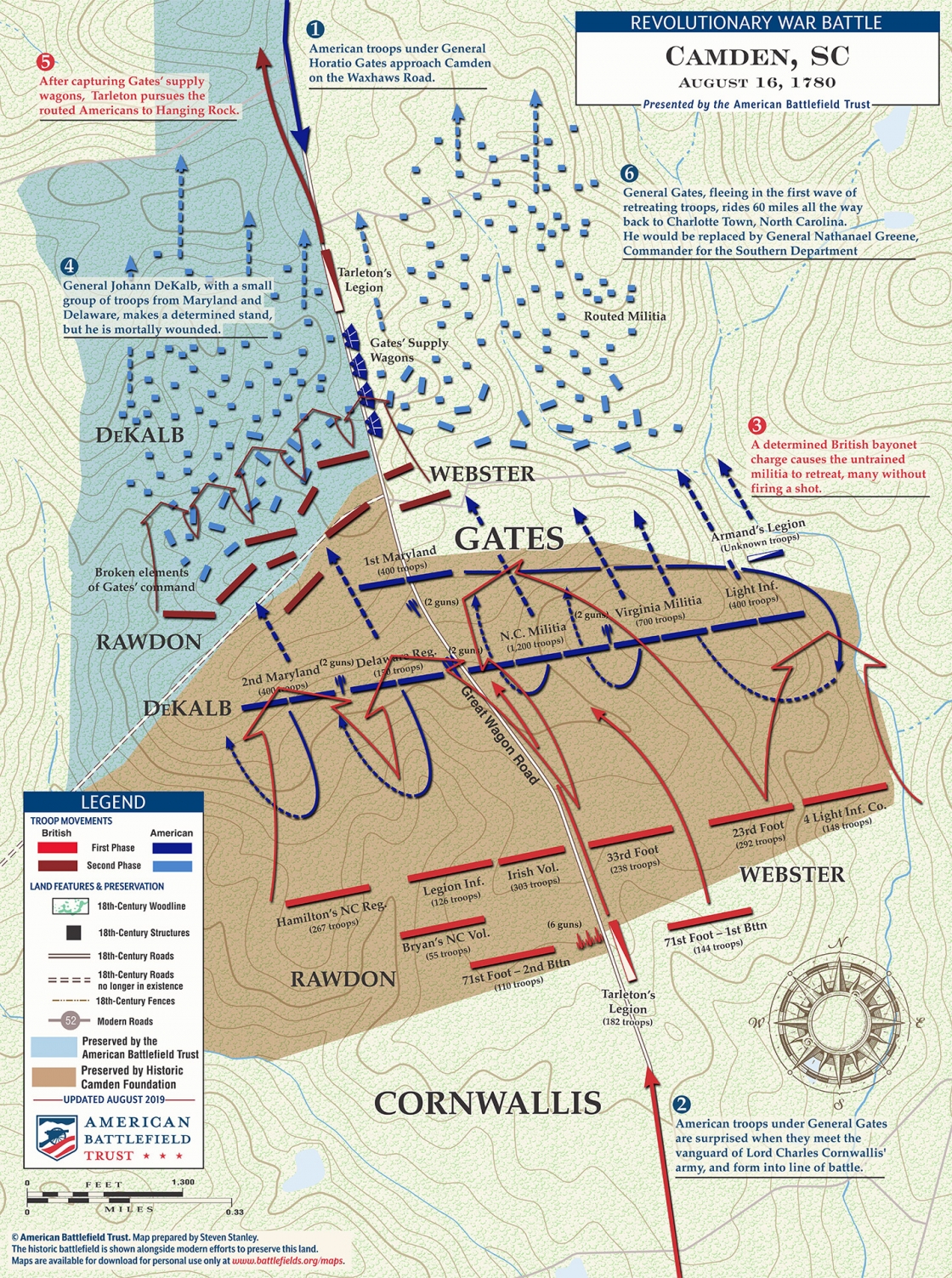

Cornwallis had marched north from Camden at 10:00 P.M. to carry out his decision to attack Gates. The opposing forces had met on the Rugeley’s Mill–Camden road, bounded in this area by open pine forest, which in turn was flanked on each side by extensive swamps. Although the Americans had the minor advantage of some slightly higher ground, the open forest to their rear widened out so that their flanks would be exposed if they were driven back. Both sides deployed with their fronts parallel, in line perpendicular to the road. On the British side, Lieutenant Colonel Webster led Cornwallis’s right wing, that is, all the units on the east side of the road. Lord Rawdon commanded the left wing, west of the road. Cornwallis’s second line, support or reserve as the situation called for, was composed of the 71st Highlanders astride the road. Behind them Tarleton’s legion was held in reserve, in column because of the terrain. The British artillery had only four guns—two six-pounders and two three-pounders—positioned in front of the center.

Gates’s army was also in two lines. Gist’s brigade of Continentals was on the right, Caswell’s North Carolina militia was in the center, and Stevens’s Virginia militia was on the left, backed up by Armand’s legion. The reserve was Smallwood’s brigade of Maryland Continentals. The American artillery was also positioned in front of the army’s center. De Kalb commanded the right wing, that is, the troops west of the road. Gates took up his own position about 600 yards behind the front line.

When artillery Captain Anthony Singleton told Otho Williams, Gates’s adjutant general, that he saw enemy infantry advancing in line of columns at several hundred yards distance, Williams told him to open fire. The adjutant general then rode back to report to Gates. When Gates appeared to be in no hurry to take any action, Williams recommended that Stevens advance and attack the enemy when they would be most vulnerable, in the act of deploying from columns into lines. According to Christopher Ward, Gates answered: “Sir, that’s right. Let it be done.” It was the last order he gave in that battle or in any other to the end of the war.

Williams had skirmishers thrown out to cover the advance of Stevens’s Virginians. Just before the Virginia militia were ready to advance, Cornwallis ordered Webster to attack the American left. The sight of ordered ranks coming at them with field music playing, drums beating the charge, regimental colors flying, and lines of glittering bayonets leveled at charge bayonet was all too much for the Virginia militia. Before the first British assault reached them, Stevens’s units broke and fled, throwing aside their muskets as they ran. Caswell’s North Carolina militia needed no prompting to follow their Virginia comrades and also took off smartly for the rear. Gates and Caswell tried to rally the fleeing men, but “they ran like a torrent, dashing past the officers and . . . spread through the woods in every direction.”

While the American left was breaking, Rawdon advanced with his wing. On the east side of the road Gist’s Continentals stood their ground, along with some North Carolina militia who had stayed to fight. By now there was so much smoke and dust obscuring the battlefield that de Kalb and his wing didn’t yet know that they were having to fight the whole battle. De Kalb went back to bring up Smallwood’s Maryland brigade in person, its commander having been carried away by the fugitives.

Cornwallis was as firmly in command of his battle as Gates was not. The British commander’s quick eye saw the opportunity to turn Webster’s regulars against the reserve brigade. The Marylanders fought back, were twice driven back and twice rallied, then were finally overcome and driven from the field.

It was Gist’s Maryland and Delaware Continentals who fought the rest of the battle—and fought it well indeed. They took on the whole of Rawdon’s wing, 1,000 to the American 600, and threw them back. Counterattacks followed each British thrust for almost an hour; at one point they broke through attacking British units to snatch 50 prisoners at bayonet point. In the midst of this fierce action de Kalb and Gist kept up the fight, still unaware that their wing was doing all the fighting. They had received no orders from Gates, and so saw no reason to save their men by falling back.