The essential weapons were a sword and a dagger. The defensive weapon was a shield either of oblong, circular or semi-circular shape, which covered the main part of the body. Each unit probably had several craftsmen to make or repair these; Lucius was for a time a shield-maker (scutarius) at Vindolanda. Weapon training was done first with wooden staves and wickerwork shields hitting against a stake. According to Vegetius these were twice as heavy as service weight. Later, real weapons would be employed. Celts, who were used to a long slashing sword, would have had to be trained in the tactics of a short stabbing sword, although the cavalry did use a longer sword (spatha). They were also used to throwing spears and javelins so throwing a pilum (a javelin usually about 2m/6 ft long) would present no difficulty. Modern experiments throwing javelins have shown that the average range is 15–20 m (16–22 yards) and that the rate of delivery can be as fast as using sling stones, although the accuracy was not as good.

By the first century AD a standard set of equipment had evolved which seems to have been made at centres in Gaul and Italy. Once the army was established in Britain armourers would provide and repair equipment at the forts, which was issued to the troops with deductions from pay. Any loss of weapons or armour merited a fine, presumably to stop weapons being sold to civilians. Legionaries wore a bronze helmet with a large flange tilted to cover the neck, flaps to cover the cheeks and a conical knob to which a plume could be attached; by the third century the helmet was becoming more conical in shape and the plume was worn only for ceremonial parades. Officers’ helmets kept a large stiff plume. A helmet found at Colchester had stylized ‘eyebrows’ on the front. Standard bearers wore an animal skin over their helmets.

Each soldier was given a tunic, a cloak and a blanket either yearly or every two years. The linen or woollen tunic was worn beneath the armour; a scarf round the neck prevented chafing. Legionaries did not at first wear breeches but as more provincial troops entered the army they brought their sartorial customs with them and it was soon realized that in the more northerly parts of the empire the winter cold made it essential to wear warmer clothing. Armour was strapped over the tunic. In 1984, a wooden chest, buried at Corbridge about AD 100, probably to save it from ravaging Caledonian tribes, was discovered to hold two sets of lorica segmentata. These were strips of metal on a base of leather straps, held together by metal hinges, thus forming a hard, movable carapace round the upper part of the body, weighing about 9 kg (20 lb). Another suit consisting of the iron bands, copper alloy studs and rivets and buckles for the leather strappings was found at Caerleon. Added metal strips on the shoulders guarded against a downward sword stroke. Olive oil was applied to keep joints from rusting. Officers wore a metal cuirass shaped like a naked torso and decorated with relief work.

Dangling metal plates attached to a belt beneath the lorica swung loosely, possibly more for decorative effect than for protection. Mail tunics or lamellar armour replaced the loricae in the late empire. Tiny pieces found at Corbridge indicate that this was made of small plates pierced by holes so that they could be lashed together to form a flexible sheet of metal. Greaves worn on the legs are indicated on the tombstone of Marcus Flavius Facilis at Colchester; these shin protectors are plain but those worn by officers were decorated with lion’s heads. Armour was probably too heavy to wear except in battle, on parade and during guard duty so off-duty dress would be a tunic and loincloth. While soldiers might have started out with the same coloured tunic, constant washing would have altered these colours so that a multicoloured array might have greeted a centurion. Unfortunately nothing is known about laundry arrangements but washerwomen in the vicus could have done this.

Thick woollen cloaks worn over the armour kept out the winter chill. The sagum was a rectangular shape and a hooded paenula drooped to a triangular point at the front. Legionaries wore brown cloaks; officers were more distinguished. Caesar speaks of his red campaign cloak. Some men may have worn the Gallic coat like the optio depicted on a tombstone at Chester. During the first century AD the usual shoe was the caliga made of hard leather with iron nails hammered so hard into the soles that they bent round. An open lattice allowed ventilation and they were held on the feet by flexible straps. The nails may have been deliberately designed to provide a crashing noise on the march and presumably intimidate people. Juvenal’s advice was not to provoke a soldier in case he kicked your shin with such a boot. They might, however, cause a problem to the wearer. Josephus recorded a soldier being killed during the attack on the temple in Jerusalem because the nails on his shoes caused him to slip, leaving him unable to defend himself.

Later a new style of shoe was adopted: a single piece of leather sewn up the front and resembling a modern climbing boot. A Vindolanda tablet referred to a balnearia or a bathing shoe with a wooden sole, which might have been worn to protect feet from the heat of the caldarium of a bathhouse. In cold weather feet would be wrapped round with cloth stuffed with wool and fur although, as already indicated, socks seemed to have been available. A bronze leg, complete to the knee, found in the River Tees at Piercebridge clearly depicts a sandal and what appears to be a woolly sock. In 2010, excavations on the A1 road between Deeping and Leeming (North Yorkshire) near the fort at Healam Bridge produced a nail of a Roman boot. On the rust appeared to be traces of fibre, possibly from a sock.

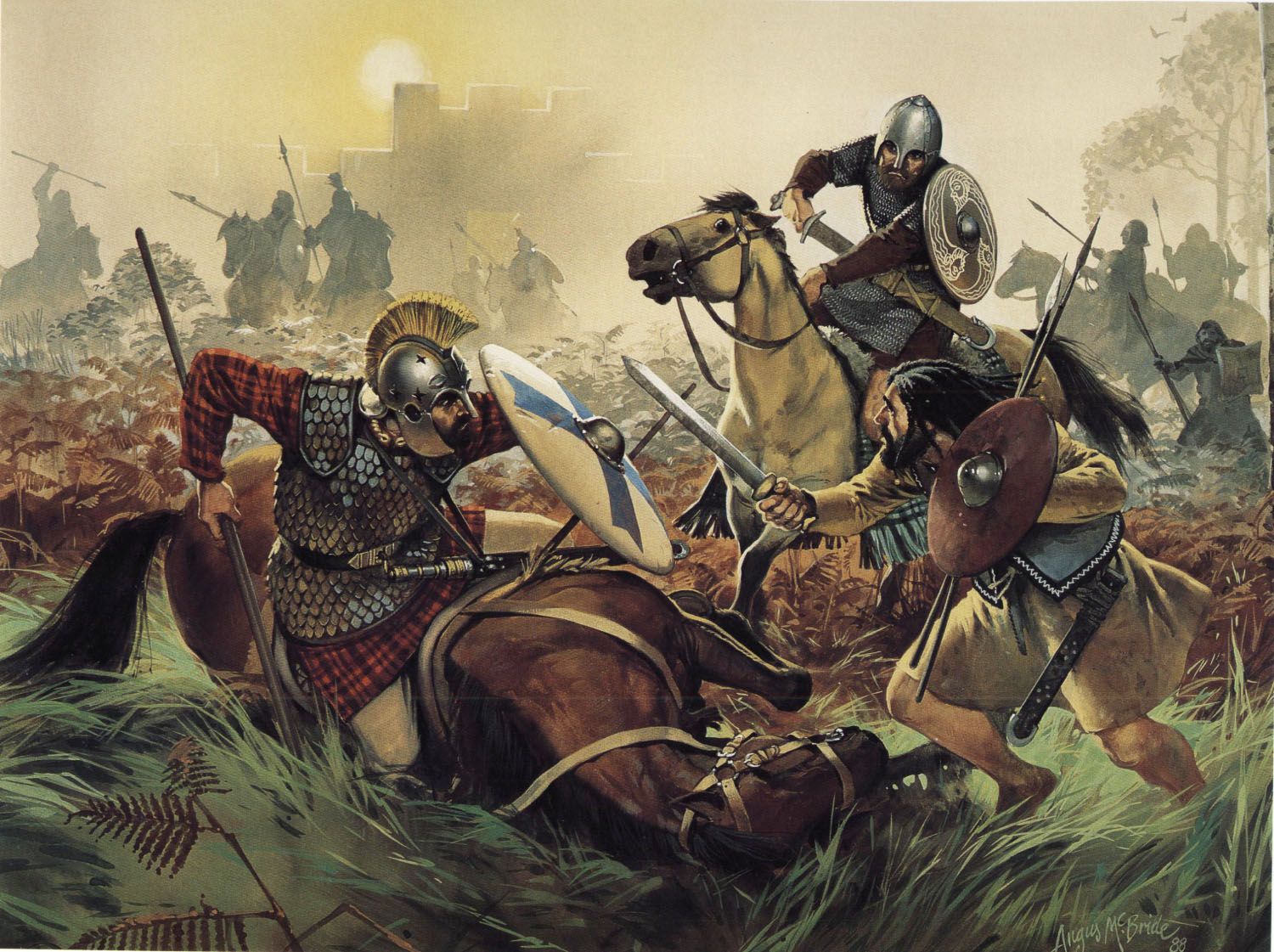

Auxilia came from far more varied backgrounds so many units wore their own dress, some wearing breeches, or using their own specialized weapons that reflected their particular fighting styles. Shields were usually oval. Most infantry cohorts wore a coat of mail (lorica hamata), which covered the body down to the hips. Later lorica squamata was introduced: rows of plates joined together by bronze wire links that were sewn on to tunics. Cavalrymen wore these split down the sides for comfort. The infantry helmets were similar to those worn by the legionaries.

Numeri used on scouting duties might be dressed little differently from the native population. Specialist groups included slingers from the Balearic Islands. Modern trials held in Turkey have confirmed the efficacy of the weapon; young men could hit a mark at 200 m (656 ft) with unerring accuracy. A soldier of the First Cohort of Hamian Archers seemingly died at Housesteads where his tombstone was erected, although his regiment was stationed at Carvoran. He was wearing a conical helmet and a coat of mail over a rough tunic. His weapons were a small bow with horn strengthening the inside of the curved wood and an axe for defence in close-quarter fighting.

Auxiliary cavalry often wore helmets with elaborately chased cheek pieces, a nose guard and a jointed neck guard. These, often gilded, took the form of an ornate facemask depicting a deity or hero. Fragments of two of these helmets have been found at Guisborough (North Yorkshire) and Worthing (Norfolk) and three complete ones at Ribchester (Lancashire), Newstead and recently at Crosby Garrett (Cumbria). The latter was in the design of a youthful handsome face, polished white, with hair of golden curls. It is the only known example of a helmet with a conical or Phrygian cap decorated with a griffin, symbol of power and protection. The pride of the men in their flamboyant appearance is summed up by Flavius Arrianus of Nicomedia who was governor in Cappadocia under Hadrian: ‘The most accomplished men wore gilded helmets with plumes fluttering in the wind, especially to draw the admiring glances of the spectators and these helmets fitted all round the faces so that it appeared as if the gods themselves were on parade.’ On ceremonial occasions the horses would wear protective clothing like the leather headgear stamped with studded patterns found at Newstead. Metal eye-guards found at Chesters and Corbridge, stamped with a trellis pattern, indicate that horses’ eyes were protected.

The tombstone of Flavinus, standard-bearer of the Ala Petriana, now in Hexham Abbey, depicts him wearing tunic, breeches, a mail tunic falling to the waist and a helmet with tall plumes set in the form of a high crest. Cavalry also used spears which were longer than those used by the infantry so that riders could thrust down at the enemy as Sextus Valerius Genialis does with his spear on his tombstone at Cirencester and Rufus Sita does at Gloucester. Stirrups had not yet been invented but a Roman saddle with high pommels would grip the rider firmly, preventing him from being unseated.

Discipline had to be kept, as was the case in any army and this was usually the task of the centurions. On his tombstone Marcus Favonius Facilis loosely holds his vine stick, the symbol of his office, which could soon strike any soldier who did not quickly obey his command. One punishment might also be docking of pay and this could affect his gratuity, for part of the pay was held back to provide money for his retirement.

More serious offences could be treated severely. Frontinus said that Augustus punished a legion that did not fight bravely by decimating every tenth man and putting the rest on barley bread. Vegetius said that men who did not reach the required standard in training could be given rations of barley instead of wheat. The ultimate punishment could be that a total unit was disbanded. The number of rebellions in Britain could indicate there were often problems. Tacitus recorded that Cohors Usiporum, raised from the Usipi in Germany, was sent to Britain for training during Agricola’s governship. They mutinied and escaped by ship, only to be defeated by the Britons when they tried to get provisions from along the coast; many were captured as slaves. Their rebellion did not succeed but a powerful leader and a promise of booty could result in soldiers following men who aspired to imperial power.

There were awards for bravery according to rank, although the corona civica, made of oak leaves, could be the reward of any soldier who saved the life of a fellow soldier. One was won by M. Ostorius Scapula, the son of Ostorius Scapula, an early governor in Britain. Centurions were awarded the corona aurea of gold and they could also win the corona muralis given to the first man who scaled and went over the wall of a besieged fort or town. The greatest honour was perhaps the corona obsidionalis or wreath of grass awarded to the deliverer of a besieged army. Presumably nothing made of precious metal could ever equal the wealth of receiving this honour. Officers of senatorial rank received a hasta pura or silver spear. All ranks could be awarded torques, armillae (bracelets) and phalerae (discs), which might be given in profusion. Single phalera have been found in Britain and nine plain roundels from Newstead possibly formed backing for a set of these.

Although the Romans were never happy when crossing the sea, they needed a navy to transport men and guard their trading interests; merchant ships could always be commandeered. One fleet, the Classis Britannica, was formed to guard the coasts of Britain and northern Gaul. Agricola used it in a scouting role to aid his land forces when he invaded Scotland. As previously mentioned, it sailed around the north of Scotland and a short way down the west coast before returning to a base on the River Tay. The oarsmen seemingly had difficulty with the strong currents in those seas. The fleet was especially useful during the campaigns of the Emperor Septimius Severus in the early third century when it acted as a support unit carrying grain from the numerous granaries at South Shields. Its main base was probably Boulogne during the first century ad, but, by the second century, it had transferred its headquarters to Dover. There it was probably concerned with the extraction of iron on the Sussex Weald. Excavations at Dover revealed four pairs of barracks each divided into eight contubernia, and with housing for the officers and non-commissioned officers. A villa at Folkestone where tiles stamped Classis Britannica have been found has been suggested as the commandant’s residence.

Men serving in the fleet would probably be volunteers: tombstones at Boulogne reveal service by a Syrian, a Tungrian and a Pannonian. These men had the same conditions of service as the auxiliaries, although the length could extend to thirty-five years. There was no career path in the Roman navy; the rank of praefectus commanding the fleet was merely a step in officer career advancement. Five men are known to have commanded the British fleet, the first three being dated to the second century. M. Maenius Agrippa began his career by commanding auxiliary regiments before becoming commander of the fleet in the 130s. He seems to have been succeeded by L. Aufidius Pantera, who set up an altar at Lympne (Kent), suitably dedicated to Neptune. Q. Baienus Blassianus, a native of Trieste on an inscription at Ostia recorded a career that included commander of the British fleet and ended with an appointment as Prefect of Egypt. A tombstone in Rome records that Sex. Flavius Quietus was promoted from the rank of primus pilus in XX Valeria Victrix to the post of praefectus of the Classis Britannica in the reigns of either Antoninus Pius or Caracalla. The last recorded evidence of the fleet is at Arles where Saturninus recorded that he was commander of the Classis Britannica Philippiana in the reign of the Emperor Philip I (AD 244–9). This was following the custom of naming units after the reigning emperor.

On the march the army was based in temporary camps, which could be organized quickly. Agrimensores (surveyors) determined the layout of the ground, the men dug a ditch using the excavated earth to form a defence, and tents were laid out in double rows facing each other. Bracken and straw provided floor covering. The Roman term for living under canvas was sub pellibus (under skin). A mass of organic material found at Birdoswald was identified as being composed of triangular and square leather pieces, used in tent-making. The leather was calfskin, chosen from the back of the beast for its consistent size and thickness. One estimate is that it would take the skins of thirty-eight calves to make one tent. The tents, 3 m (10 ft) square, each housed eight men; centurions’ tents were placed at the ends of the rows. Arms and other equipment were stacked in the front and the baggage train was accommodated behind. Senior officers would have still larger tents placed in the centre of the camp and that of the commanding officer could be quite luxurious. Suetonius records that Caesar carried with him tessellated and mosaic floors on campaigns, presumably both for comfort and to impress visiting chieftains.

Fortresses were permanent bases housing the whole legion, covering on average 20 hectares (50 acres); in Britain there were ten at one time or another. Auxiliary units and vexillations of legionaries and auxiliaries were housed in forts of standard measurement and in logical layout so that soldiers, who might move from fort to fort, would realize in any emergency what route they had to follow to reach their posts. The largest fortress in Britain covered over 24 hectares (60 acres), the smallest fort less than 0.20 hectares (0.5 acre). Their size varied as to whether they housed large or small military units, infantry or cavalry, or mixed garrisons. Colchester, 20 hectares (49 acres), housed Legion XX. Hod Hill, 4 hectares (9.6 acres), housed a mixed garrison of legionaries and auxiliaries, which was necessary during the first century to ensure the successful control of that area after the invasion.

Forts were usually oblong or square-shaped with gates on each side, opposite to each other. A main street (via principalis) ran between the main gates in the long side of the fort and another street (via praetoria) ran from the front gate (porta praetoria), set in the centre of the short side of the fort, to join the via principalis in front of the headquarters building (principia). To the rear of the principia the line of the via praetoria was continued by the via decumana which ran down to the rear gate (porta decumana) in the centre of the second short side. The principia, the administrative centre of the fort, was so important that temporary accommodation was often provided while the rest of the fort was built. A defensive space, the via sagularis, so-called from the sagum or cloak which the soldier wore when he left the fort, ran between the barracks and the wall.

Buildings were of stone and timber and were renewed when necessary; many timber forts were rebuilt in stone in the second century. If a fort had been abandoned and then reoccupied the buildings were usually rebuilt to the same pattern. Timber forts would need the felling of 6.6–12.5 hectares (16–30 acres) of wood to supply the necessary material. Stone forts used material from the nearest quarry. Banks and ditches provided defence. Soldiers from the Royal Engineers, aided by Borstal Boys, built a reconstructed rampart at the Lunt fort at Baginton. This was based on the presumed Roman measurements of 5.5 m (18 ft) wide at the base, with an earth core faced back and sides by cut turfs, and narrowing to 1.8m (6 ft) at the top. It gave a height of 3.65 m (12 ft) to which a breastwork was added.

In the second century the front of a rampart was often cut back to insert a stone wall. The Ala Hispanorum Vettonum did this at Brecon Gaer (Powys) about AD 140. The rampart walk would continue across the gateways, two or four in number, often with double passageways, which would secure the weak entrance points. The stone pivots on which stout wooden gates would swing can still be seen at Brecon Gaer. Over the main gateway of the fort would be placed a carved stone or wooden panel giving the name of the unit and the date of its erection, which usually included the name of the emperor. The south-east fortress gateway of York was dominated by that recording its building in the reign of Trajan by Legion IX.

The two most prominent buildings were the headquarters building (principia) and the commandant’s house (praetorium). The principia consisted of a crosshall, possibly large enough for the whole garrison to meet, an aedes (shrine) and a forecourt surrounded by a veranda. The aedes, opening off the crosshall, was the focus of the headquarters building and therefore of the fort, where standards were kept, together with a statue of the emperor and altars dedicated to protecting deities of the unit. At Caerleon there were benches on which standards could be placed. At High Rochester an altar set up in the third century to the Genius of the Emperor and to the standards of the Cohors I Vardulli and of the numerus Exploratorum Bremeniensium may have been intended either to promote harmony between two very different units or to indicate that they shared the fort in mutual respect. Corbridge and Vindolanda had carved stone friezes showing the standards.

Statues of deities and emperors were placed in the crosshall; bases remain at Housesteads and York and fragments of bronze statues were found in a number of forts. From the forecourt rooms might lead off for other activities. One might be an armamentarium or weapon store, although an inscription at Lanchester (County Durham) indicates that the weapon store was a completely separate building. A well provided water for drinking or to be used in religious ceremonies. When the Bar Hill principia was demolished, the well was used as a refuse pit for column shafts and capitals.

At first, the regimental pay-chest, containing the funds of the unit and the savings of the soldiers, was kept in the shrine. Later these were placed in a strong room under the shrine. There was a strong door at Chesters; at High Rochester, a stone slab, balanced on iron wheels to slide it across, assured even more security. At Brough-by-Bainbridge (North Yorkshire), the pit was lined with concrete. There were huge strong rooms at South Shields and Maryport possibly because large sums of money were held at these supply bases. At Housesteads and Vindolanda excavations revealed that the soldiers’ pay could be issued from counters guarded by stone screens and grills.

The praetorium was usually placed by the side of the principia. This could be a palatial building in a fortress, especially in the third century when the legate of Legion VI at York was also governor of Britannia Inferior. Every commanding officer, however, expected to have comfortable quarters, especially if he had a wife and children, and brought many of his own possessions with him. The presence of a wife is known at one fort by an invitation on a wooden tablet found at Vindolanda. Sulpicia Lepidina had accompanied her husband, Flavius Cerialis, prefect of Cohort IX of Batavians, to Vindolanda at the end of the first century AD. A friend or relative, Claudia Severa, whose husband, Aelius Brocchus, commanded a fort called Briga, probably Kirkbride, near Carlisle, invited her to her birthday party on the third day before the Ides of September, sometime in the year AD 100. If Sulpicia had accepted, a military escort would have had to be provided across 55 km (35 miles) of rough country. This invitation seems to have been written by a scribe, but to make sure that Sulpicia came Claudia pressed her, saying that this would ‘make the day more enjoyable by your presence’. She added in her own hand, ‘I will expect you sister. Farewell sister, my dearest soul as I hope to prosper, and greetings.’

Comfort in the praetorium would have included rooms heated with a hypocaust. Imposing quarters were needed to impress fellow officers, visiting officials and native tribesmen, and to act as a model to encourage civilian guests to realize the comforts of Roman civilization. At Caerleon the praetorium included a long colonnaded area with apsidal ends, possibly laid out as a garden, where business was concluded or where visiting dignitaries and fellow officers were entertained before a meal. The praetorium at South Shields seems to have had summer and winter dining rooms. Even in the smaller forts auxiliary commanders and legionary tribunes expected to be housed in accordance with their rank. Praetoria seem to have been based on the model of the Mediterranean house with rooms arranged round a central courtyard and including a private bathhouse like that at Chesters. Several forts have evidence for private latrines placed within the commandant’s house. If the commandant was not married the military tribunes could have used this accommodation as a clubhouse, otherwise they would be accommodated in courtyard houses.