The treaty with Guthrum gave Alfred the breathing space he needed to fortify and revitalize Wessex. As the last outpost of independent England, it was essential for Wessex to have an efficient military.

Alfred the Great reorganized Wessex’s army, keeping half of the men on duty at any given time. And although Alfred is famous as the father of the English Navy, kings before Alfred had used war ships. Nonetheless, recognizing that swift ships were just one more advantage the Vikings held over the English, Alfred brought over from Frisia (modern-day Holland) skilled shipwrights to build his new navy.

Guthrum gave Alfred seven years to rebuild his kingdom, but then the double-dealing Viking broke the treaty and invaded Wessex in 885 and laid siege to Rochester. But Alfred’s new military defensive measures worked. Mobilizing his standing army, his burh garrisons, and his navy, he broke the Danish siege easily, then sent his fleet up the River Thames to capture London.

In 886, after seventeen years of occupation under the Vikings, London was in English hands again. Alfred pressed his advantage by requiring, in a new treaty with Guthrum, that English Christians under Viking rule in the Danelaw enjoy the same legal protections as the settlers from Scandinavia; beaten and humiliated, Guthrum agreed. Four years later, Guthrum, apparently without giving Alfred any more trouble, died in Hadleigh.

The Invasions Continue

In spite of Guthrum’s defeat and death, the Vikings continued to mount sporadic raids on Alfred’s territory. But a serious invasion with eighty ships was mounted from France in 892, led by a Viking chief named Hastein who had been terrorizing the inhabitants of the Loire Valley. He ordered part of his force to disembark in Kent, then beached his ships at Benfleet in Essex. Danes from East Anglia and York joined Hastein’s army, but once again Alfred’s military proved its worth. The infantry harried the Vikings, while Alfred’s navy destroyed many of Hastein’s long ships in a battle off the coast of Devon in 893. After several more reverses on land, Hastein and most of his army retreated up the old Roman road, Wading Street, to Chester.

Bad luck pursued Hastein’s army for another three years. The Vikings abandoned Chester in 894 and invaded northern Wales, but the ferocious resistance of the Welshmen and the lack of supplies forced the Vikings to retreat. The next year they attempted to establish a base on the River Lea north of London, no doubt positioning themselves to take the city back from Alfred, but the English hit them so hard that the Vikings had to retreat for safety into the Danelaw, leaving their dragon ships behind. In 896, the Vikings were encamped along the Severn when Alfred attacked again. The Vikings scattered: Some went north to York, and others sailed back to France in hope of easier plunder.

Building a Navy

The decades of struggle between the Danish raiders and the people of Wessex, waxed and waned. Often defeated, sometimes victorious, it is recorded that Alfred remained resolute and positive and carried his army with him. They trusted him to lead them and followed his commands absolutely. He was a good strategist and it was during his reign that the building of ships to defeat the Danes before they made land, began.

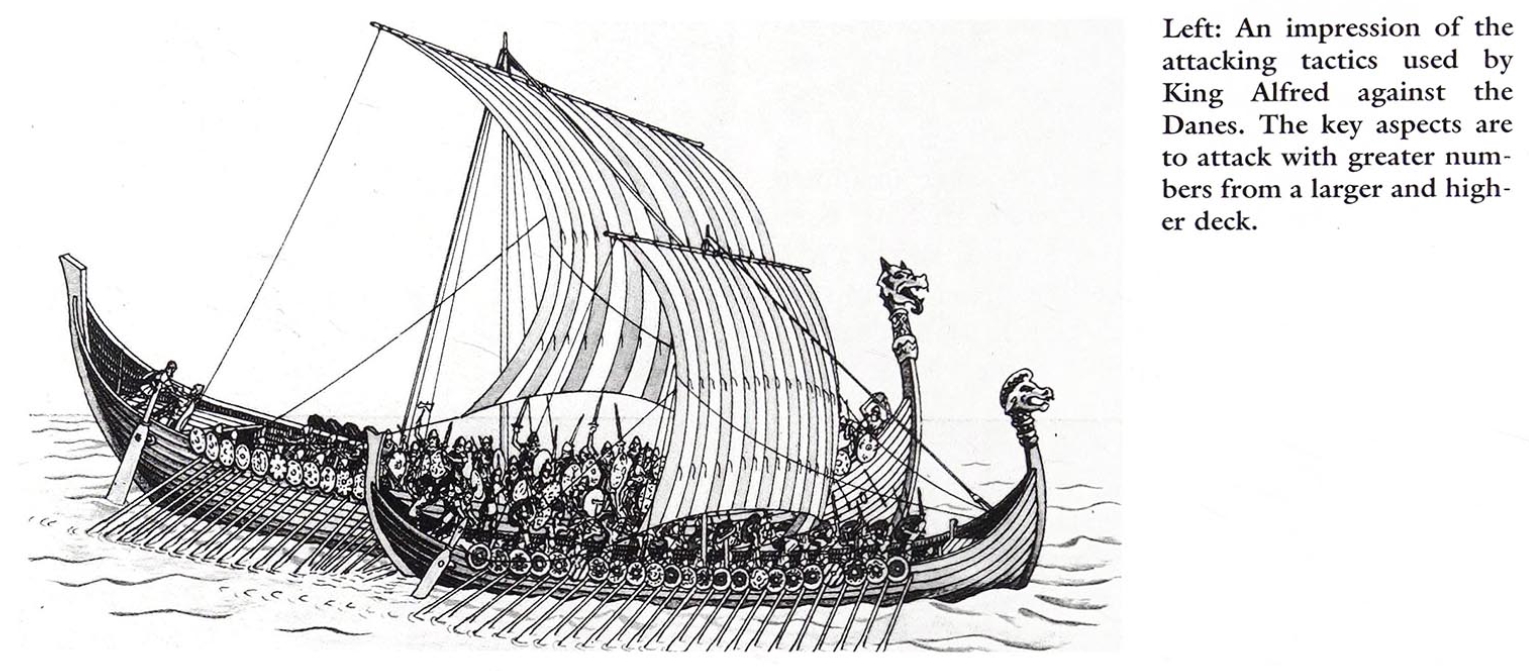

The Anglo Saxon Chronicle tells us that Alfred ordered the ships to be built to oppose the ‘esks’, the Danish vessels. It appears that Alfred himself designed the ships, he wanted a ship that would be more efficient than the Danes. Longer, steadier, higher and swifter. Some had sixty oars or more.

It is worth reading the Anglo Saxon Chronicle at this point, as it explains quite clearly the events that led to the construction of King Alfred’s Navy

A.D. 897. In the summer of this year went the army, some into East-Anglia, and some into Northumbria; and those that were penniless got themselves ships, and went south over sea to the Seine. The enemy had not, thank God. entirely destroyed the English nation; but they were much more weakened in these three years by the disease of cattle, and most of all of men; so that many of the mightiest of the king’s thanes. that were in the land, died within the three years. Of these. one was Swithulf Bishop of Rochester, Ceolmund alderman in Kent, Bertulf alderman in Essex, Wulfred alderman in Hampshire, Elhard Bishop of Dorchester, Eadulf a king’s thane in Sussex, Bernuff governor of Winchester, and Egulf the king’s horse-thane; and many also with them; though I have named only the men of the highest rank. This same year the plunderers in East-Anglia and Northumbria greatly harassed the land of the West-Saxons by piracies on the southern coast, but most of all by the esks which they built many years before.

Then King Alfred gave orders for building long ships against the esks, which were full-nigh twice as long as the others. Some had sixty oars, some more; and they were both swifter and steadier, and also higher than the others.

They were not shaped either after the Frisian or the Danish model, but so as he himself thought that they might be most serviceable. Then, at a certain turn of this same year, came six of their ships to the Isle of Wight; and going into Devonshire, they did much mischief both there and everywhere on the seacoast. Then commanded the king his men to go out against them with nine of the new ships, and prevent their escape by the mouth of the river to the outer sea. Then came they out against them with three ships, and three others were standing upwards above the mouth on dry land: for the men were gone off upon shore. Of the first three ships they took two at the mouth outwards, and slew the men; the third veered off, but all the men were slain except five; and they too were severely wounded. Then came onward those who manned the other ships, which were also very uneasily situated. Three were stationed on that side of the deep where the Danish ships were aground, whilst the others were all on the opposite side; so that none of them could join the rest; for the water had ebbed many furlongs from them. Then went the Danes from their three ships to those other three that were on their side, be-ebbed; and there they then fought.

There were slain Lucomon, the king’s reve, and Wulfheard, a Frieslander; Ebb, a Frieslander, and Ethelere, a Frieslander; and Ethelferth, the king’s neat-herd; and of all the men, Frieslanders and English, sixty-two; of the Danes a hundred and twenty. The tide, however, reached the Danish ships ere the Christians could shove theirs out; whereupon they rowed them out; but they were so crippled, that they could not row them beyond the coast of Sussex: there two of them the sea drove ashore; and the crew were led to Winchester to the king, who ordered them to be hanged. The men who escaped in the single ship came to East-Anglia, severely wounded. This same year were lost no less than twenty ships, and the men withal, on the southern coast. Wulfric, the king’s horse-thane, who was also viceroy of Wales, died the same year.

It is thought that the boat yards would therefore have had to have been sufficiently close to Alfred’s household at Winchester, so that he could oversee the building of his ships. One of his yards was quite probably on the Itchen at Southampton, where succeeding monarchs also built ships.

The great forests of Hampshire would have yielded plenty of wood for the construction of the ships and the mouth of the Itchen an excellent launching site.

In AD897 King Alfred’s Navy was put to the test, when a fleet of Danish boats sailed up the Solent. Alfred’s ships sailed out to confront them and a major battle ensued with great losses on both sides. The Danes were eventually defeated and those captured taken to Winchester where Alfred had them hung as pirates.