Despite the general demoralisation, there was still a nucleus of disciplined men in most units, and many regiments found reinforcements in Smolensk, in the shape of echelons sent from depots in France, Germany or Italy. Pelet’s regiment, for instance, had shrunk to six hundred men but found a couple of hundred uniformed and armed men waiting for them. Raymond de Fezensac’s 4th of the Line was down to three hundred, but was joined by two hundred fresh men. The only problem with these men was that they had not been through the same tempering process as their comrades, and they were not up to dealing with the conditions. The 6th Chasseurs à Cheval received 250 recruits from their depot in northern Italy, but the shock to their system was such that not one of them was alive a week later.

The loss of up to 60,000 men and possibly as many as 20,000 camp followers since leaving Moscow could, theoretically, have been to Napoleon’s advantage. Caulaincourt was one of those who believed that if a couple of hundred cannon had been thrown into the Dnieper, along with the wagons carrying the trophies from Moscow, and all the wounded left in Smolensk with medical attendants and supplies, liberating thousands of horses, the slimmed-down but more mobile force of 40,000 or so men could have operated in a more aggressive manner and fed itself more easily. He blamed Napoleon for failing to take stock of the situation. ‘Never has a retreat been less well ordered,’ he complained.

It is certainly true that Napoleon’s unwillingness to lose face prevented him from taking drastic measures and making a dash for Minsk and Vilna. He put off every decision to fall back further until the very last moment. ‘In that long retreat from Russia he was as uncertain and as undecided on the last day as he was on the first,’ wrote Caulaincourt. As a result, even the march could not be organised properly by the staff.

But the real problem vitiating any attempt to reorganise the Grande Armée was that at every stop along the line of retreat it picked up fresh troops, who were often more of a liability than an asset, as well as commissaires, local collaborators, wounded and sick who had been left behind on the advance, and all the riff-raff who had been infesting the area under French occupation. As the Grande Armée retreated, it pushed all this dead weight before it, and had to march through it, losing resources and gaining chaos in the process.

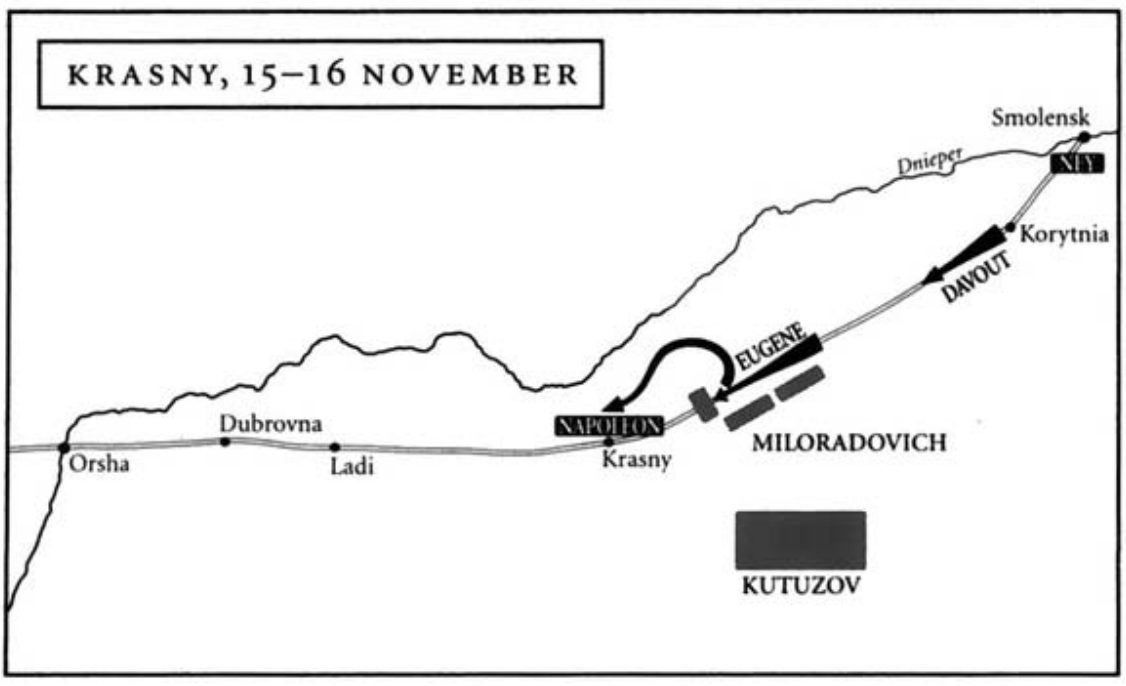

Napoleon still entertained hopes of halting the retreat at Orsha or, failing that, along the line of the river Berezina. After four days in Smolensk, he sent the remnants of Junot’s and Poniatowski’s corps ahead, and left the city himself on the following day, 14 November, preceded by Mortier with the Young Guard and followed by the Old Guard. Prince Eugène, Davout and Ney were to follow at one-day intervals.

The going was hard, through deep snow which became slippery when compacted by the tramp of feet and hooves. There were many slopes in the road testing men and horses, and a number of bridges over small ravines causing bottlenecks. On the evening of the first day out of Smolensk, Colonel Boulart with part of the artillery of the Guard got stuck at a bridge which was followed by a steep rise. There was the usual jam of people, horses and vehicles, all vying for precedence, and every so often cossacks would ride up and cause panic. The Russians had now placed light guns on sleighs, which meant they could be brought up, fired and pulled away before the French had time to unlimber their cannon and fire back. Boulart realised that if he did not take decisive action, his battery would disintegrate in the midst of the jam. He therefore forced a passage for himself, by over-turning civilian vehicles or pushing them off the road. He got his men to dig under the snow on either side of the road until they found earth, and to sprinkle this on the icy surface of the road leading up the slope, which he also broke up with picks. It took him all night to get his cannon across the bridge and up the slope. ‘I fell heavily at least twenty times as I went up and down that slope, but, sustained as I was by the determination to succeed, I did not let this hinder me,’ he wrote.

While Boulart struggled with his guns, Napoleon, who had stopped at Korytnia for the night, called Caulaincourt to his bedside and again talked of the necessity of his going back to Paris as soon as possible. He had just heard that Miloradovich had cut the road ahead of him near Krasny. He could not rule out the possibility of being taken, and his close encounter with the cossacks outside Maloyaroslavets had unnerved him. In order to arm himself against capture he bade Dr Yvan prepare him a dose of poison, which he henceforth wore in a small black silk sachet around his neck.

The following morning, 15 November, Napoleon fought his way through to Krasny, where he paused to allow those behind him to catch up. But Miloradovich had closed the road once more behind him, and when Prince Eugène’s Italians, now not much more than four thousand strong, came marching down it the following afternoon they in turn found themselves cut off. Massed ranks of Russian infantry supported by guns barred the road in front of them, while cavalry and cossacks hovered on their flanks. Miloradovich sent an officer under a white flag to inform Prince Eugène that he had 20,000 men and that Kutuzov was nearby with the rest of the Russian army. ‘Go back quickly whence you came and tell him who sent you that if he has 20,000 men, we are 80,000!’ came the reply. Prince Eugène unlimbered his remaining ten guns, formed up his corps into a dense column and forged ahead.

The Russians, who could see how few of them there were, once again summoned them to surrender. When this was rejected, they opened fire, and a fierce and bloody fight ensued. ‘We fought until nightfall without giving ground,’ recalled one French officer, ‘but it fell just in time; one more hour of daylight and we would probably have been overpowered.’ The Russians were nevertheless still between them and Krasny, and would easily crush them on the following day. In the circumstances, Prince Eugène could see no way out other than to fall in with the plan of a Polish colonel attached to his staff. When darkness fell, he formed up his remaining men in a compact file and, leaving behind all unnecessary impedimenta, marched off the road, into the woods, and across country round the side of the Russian army. When challenged by Russian sentries, the Polish colonel marching at the head of the column brazenly replied in Russian that they were on a special secret mission by order of His Serene Highness Field Marshal Prince Kutuzov. Unbelievably, the ploy worked, and in the early hours, just as Miloradovich was preparing to finish it off, the 4th Corps marched into Krasny behind his back.

Napoleon was relieved to see his stepson, but he was now in something of a quandary. He ought to wait for Davout and Ney, in case they too had difficulty in breaking through Miloradovich’s roadblock, but he was in peril of being stranded himself, as Kutuzov had turned up a couple of miles to the south of Krasny, and could easily cut the road between him and Orsha. In order to gain time, he decided to take the field himself at the head of his Guard.

Walking in front of his grenadiers, Napoleon led them out of Krasny back onto the Smolensk road and then turned them to face the Russian troops who had massed in a long formation to the south of the road. ‘Advancing with a firm step, as on the day of a great parade, he placed himself in the middle of the battlefield, facing the enemy’s batteries,’ in the words of Sergeant Bourgogne. He was vastly outnumbered, but his bearing, standing calmly under fire as the Russian shells struck men all around him, seems to have impressed not only his own men but the enemy as well. Miloradovich moved back from the road, leaving it open for Davout to march through. And Kutuzov resisted the entreaties of Toll, Konovnitsin, Bennigsen and Wilson, who could all see that the Russians were in a position to encircle Napoleon and overwhelm him by sheer weight of numbers, ending the war there and then.

Napoleon was alarmed to discover that Davout had hurried on westwards without waiting for Ney, who was still some way behind. But he could not afford to wait any longer himself, as Kutuzov had by now turned his wing and threatened his line of retreat to Orsha. He left Mortier and the Young Guard to hold Krasny and cover Davout’s retreat, and himself marched through the town and out onto the Orsha road, at the head of the Old Guard.

It was not long before he came up against a horde of civilians and deserters who had gone on ahead and, finding the road cut by the Russians, come rushing back in a panic. Napoleon steadied them, but not before they had caused chaos in the ranks and among the wagons following the staff, with the result that some careered off the road and sank in the deep snow covering the boggy ground on either side of it.

As the French resumed their march, they were caught in a murderous enfilading fire from the Russian guns. The last of Latour-Maubourg’s cavalry struggled to keep cossacks and Russian cavalry at bay, while the dense column of men and vehicles made its way down the cluttered road. Colonel Boulart, who had managed to keep all his guns thus far, had a terrible job getting them through here too. The civilians and men who had left the ranks were getting in the way, and their skidding vehicles obstructed the road. Boulart cleared some ground at the side of the road, and, one by one, led his gun teams round the jam. But the chaos increased as the Russian artillery were now shelling the bottleneck, and when he went back for his last gun he found it impossible to move it among the exploding shells, so he spiked and abandoned it. As he struggled free of the mass of civilians with his last team, he saw a harrowing sight. ‘A young lady, a fugitive from Moscow, well-dressed and with striking looks, had managed to free herself from the mêlée and was moving ahead with great difficulty on the donkey she was riding, when a cannonball came and shattered the poor animal’s jaw,’ he wrote. ‘I cannot express the feeling of sorrow I carried away with me as I left that unfortunate woman, who would betimes become the prey and possibly the victim of the cossacks.’

In an effort to push back the Russian guns, the infantry made a number of exhausting bayonet attacks through the deep snow, in which hundreds perished. Colonel Tyndal’s Dutch Grenadiers, whom Napoleon used to call ‘the glory of Holland’, lost 464 men out of five hundred. The Young Guard was virtually sacrificed in the process of covering the withdrawal. The Russians kept out of musketshot and merely shelled them, but in the words of General Roguet, ‘they killed without vanquishing … for three hours these troops received death without making the slightest move to avoid it and without being able to return it’.

Luckily for the French, Kutuzov refused to reinforce the troops barring the road once he heard that it was Napoleon himself who was marching down it. Many on the Russian side felt a deep-seated reluctance to take him on, and preferred to stand by in awe. ‘As on the previous days, the Emperor marched at the head of his Grenadiers,’ recalled one of the few cavalrymen left in his escort. ‘The shells which flew over were bursting all round him without his seeming to notice.’ But this heroic day ended on a less solemn note as they reached Ladi late that afternoon. The approach to the town was down a steep icy slope. It was utterly impossible to walk down, so Napoleon, his marshals and his Old Guard had no option but to slide down it on their bottoms.

The Emperor struck a more serious tone the following day at Dubrovna, where he assembled his Guard and addressed the dense ranks of bearskins. ‘Grenadiers of my Guard,’ he thundered, ‘you are witnessing the disintegration of the army; through a deplorable inevitability the majority of the soldiers have cast away their weapons. If you imitate this disastrous example, all hope is lost. The salvation of the army has been entrusted to you, and I know you will justify the good opinion I have of you. Not only must officers maintain strict discipline, but the soldiers too must keep a watchful eye and themselves punish those who would leave the ranks.’ The grenadiers responded by raising their bearskins on their bayonets and cheering.

Mortier made a similar speech to what was left of the Young Guard, which responded with shouts of ‘Vive l’Empereur!’ A little further back in the marching order, General Gérard applied more summary methods when a grenadier of the 12th of the Line dropped out of the ranks announcing that he would not fight any more. He rode up to the man, drew his pistol from the saddle holster and, cocking it, announced that he would blow his brains out if he did not return to his place at once. When the soldier refused to obey, the General shot him. He then made a speech, telling the men that they were not garrison troops but soldiers of the great Napoleon, and that consequently much was expected of them. They responded with shouts of ‘Vive l’Empereur! Vive le Général Gérard!’

Later on that same day, 19 November, Napoleon reached Orsha, where he hoped to be able to rally the remains of his army. The city was reasonably well stocked with provisions and arms. ‘A few days’ rest and good food, and above all some horses and artillery will soon put us right,’ he had written to Maret from Dubrovna the previous day. He issued a proclamation giving assembly points for each corps, warning that any soldier found in possession of a horse would have it taken away for the use of the artillery, that any excess baggage would be burnt, and that soldiers who had left their units would be punished. He himself took up position at the bridge over the Dnieper leading into the town, ordering excess private vehicles to be burnt and unauthorised soldiers to give up their mounts. He then posted gendarmes there to carry on in his place and to direct incoming men to their respective corps and inform them that they would be fed only if they rejoined the colours.

Watching the men streaming into town can only have heightened Napoleon’s anxiety over Ney, who seemed irretrievably lost. That evening he paced the room he had occupied in the former Jesuit convent, cursing Davout for not having waited for Ney and declaring that he would give every one of the three hundred million francs he had in the vaults of the Tuileries to get the Marshal back. His anxiety was shared by the whole army, which held the brave and forthright Ney in high esteem. ‘His rejoining the army from beyond Krasny seemed impossible, but if there was one man who could achieve the impossible, everyone agreed, it was Ney,’ recorded Caulaincourt. ‘Maps were unfolded, everyone pored over them, pointing out the route by which he would have to march if courage alone could not open the road.’

Ney had been the last to march out of Smolensk, amid harrowing scenes, on the morning of 17 November. He had been ordered by Napoleon to blow up the city fortifications, and his unfortunate aide-de-camp Auguste Breton was given the job of setting the charges and then visiting the hospitals in order to inform the inmates that the French were leaving. ‘Already the wards, the corridors and the stairs were full of the dead and dying,’ he recorded. ‘It was a spectacle of horror whose very memory makes me shudder.’ Dr Larrey had put up large notices in three languages begging for the wounded to be treated with compassion, but neither he nor they had any illusions. Many of them crawled out into the road, begging in the name of humanity to be taken along, terrified at the prospect of being left at the mercy of the cossacks.

Ney’s corps by now numbered some six thousand men under arms, and was followed by at least twice as many stragglers and civilians. He marched along a road strewn with the usual traces of retreat, but beyond Korytnia the following morning he found himself crossing what was patently the scene of a recent battle. And that afternoon, 18 November, he himself came face to face with Miloradovich, who, having failed to capture Prince Eugène and then Davout, was determined not to miss his third chance.

He sent an officer with a flag of truce calling on Ney to surrender, to which the latter answered that a Marshal of France never surrendered. Ney then drew up his forces, opened up with the six guns he had left, and launched a bold frontal assault on the Russian positions. It was carried out with such élan that it nearly succeeded in overrunning the Russian guns barring the way, but the French ranks were raked with canister shot and a countercharge by Russian cavalry and infantry sent them reeling back. Not to be deterred, Ney mounted a second attack, and his columns advanced with remarkable determination under a hail of canister shot. It was ‘a combat of giants’ in the words of General Wilson. ‘Whole ranks fell, only to be replaced by the next ones coming up to die in the same place,’ according to one Russian officer. ‘Bravo, bravo, Messieurs les Français,’ Miloradovich exclaimed to a captured officer. ‘You have just attacked, with astonishing vigour, an entire corps with a handful of men. It is impossible to show greater bravery.’

But before long the French were beaten back once again. Colonel Pelet, who was in the front rank with his 48th of the Line, was wounded three times and saw his regiment decimated. The neighbouring 18th of the Line was reduced from six hundred men to five or six officers and twenty-five or thirty men, and lost its eagle in the attack. Fezensac’s 4th lost two-thirds of its effectives. Woldemar von Löwenstern, who had been watching the proceedings from the Russian positions, galloped back to Kutuzov’s headquarters and announced that Ney would be their prisoner that night.

But this forty-three-year-old son of a barrel-maker from Lorraine was not so easily accounted for. Touchy and headstrong, Ney was furious when he realised that he had been left to fend for himself by Napoleon. ‘That b—has abandoned us; he sacrificed us in order to save himself; what can we do? What will become of us? Everything is f—ked!’ he ranted. But it would take more than that to shake his loyalty to Napoleon. And if he was not the most intelligent of Napoleon’s marshals, he was resourceful and certainly one of the bravest. After some discussion with his generals, he decided to try to give the Russians the slip by crossing the Dnieper, which flowed more or less parallel with the road some distance away, and then making for Orsha along its other bank, thus bypassing Miloradovich and putting the river between himself and the Russians.

While he made a show of settling down for the night, Ney sent a Polish officer to reconnoitre the banks of the Dnieper in search of a place to cross. A place was found, and that night, after having carefully stoked up enough bivouac fires to give the impression that the whole corps was camping there, Ney led the remainder of his force – not much more than a couple of thousand men – off the Smolensk – Orsha road and into the woods to the north of it. It was an exhausting and difficult march, particularly as he was still dragging his last few guns and as many supply wagons as he could through the deep snow. ‘None of us knew what would become of us,’ recalled Raymond de Fezensac. ‘But the presence of Marshal Ney was enough to reassure us. Without knowing what he intended to do or what he was capable of doing, we knew that he would do something. His self-confidence was on a par with his courage. The greater the danger, the stronger his determination, and once he had made his decision he never doubted its successful outcome. Thus it was that at such a moment his face betrayed neither indecision nor anxiety; all eyes were upon him, but nobody dared to question him.’

They soon got lost and disoriented, but Ney spotted a gully which he assumed to be the bed of a stream. Digging through the snow they found ice, and when they broke that they saw from the direction of flow which way they must follow it. They eventually came to the Dnieper, which was covered with a coating of ice thick enough to take the weight of men and horses spaced out, but not to support large groups or cannon drawn by teams of horses.

The men began to cross, leaving spaces between each other, prodding the ice in front with their musket butts as it groaned ominously. ‘We slithered carefully one behind the other, fearful of being engulfed by the ice, which made cracking sounds at every step we took; we were moving between life and death,’ in the words of General Freytag. As they reached the other bank, they came up against a steep and slippery incline. Freytag floundered helplessly until Ney himself saw him and, cutting a sapling with his sabre, stretched out a helping limb and pulled him up.

Some mounted men and then a few light wagons did get across, encouraging others to try but weakening the ice in the process. More wagons ventured onto it, including some carrying wounded men, but these foundered through the ice with sickening cracks. ‘All around one could see unfortunate men who had fallen through the ice with their horses, and were up to their shoulders in the water, begging their comrades for assistance which these could not lend without exposing themselves to sharing their unhappy fate,’ recalled Freytag; ‘their cries and their moans tore at our hearts, which were already strongly affected by our own peril.’

All of the guns and some three hundred men were left behind on the south bank, but Ney had got over with the rest and soon found an unravaged village, well stocked with food, in which they settled down to rest. The following day they set off across country in a westerly direction. It was not long before Platov, who had been following the French retreat along the north bank of the river, located them and began to close in. Ney led his men into a wood, where they formed a kind of fortress into which the cossacks dared not venture. Platov could do no more than shell them with his light field-pieces mounted on sleigh runners, but this produced little effect.

At nightfall, Ney moved off again. They trudged through knee-deep snow, stalked by cossacks who sometimes got a clear enough field of fire to shell them. ‘A sergeant fell beside me, his leg shattered by a carbine shot,’ wrote Fezensac. ‘“I’m a lost man, take my knapsack, you might find it useful,” he cried. Someone took his knapsack and we moved off in silence.’ Even the bravest began to talk of giving up, but Ney kept them going. ‘Those who get through this will show they have their b—s hung by steel wire!’ he announced at one stage.

Unsure of his bearings, Ney sent a Polish officer ahead. The man eventually stumbled on pickets of Prince Eugène’s corps outside Orsha, and as soon as he was informed of Ney’s approach, Prince Eugène himself sallied forth to meet him. Eventually, Ney’s force, now not much more than a thousand men in the final stages of exhaustion as they stumbled through the night, heard the welcome shout of ‘Qui vive?’, to which they roared back: ‘France!’ Moments later Ney and Prince Eugène fell into each other’s arms, and their men embraced each other with joy and relief.