The interacting deconstructions have in turn generated opportunities for reconstruction. Blitzkrieg was certainly not a comprehensive principle for mobilizing Germany’s resources for a total war waged incrementally. Nor was it a structure of concepts like Air Land Battle or counterinsurgency, expressed in manuals, taught in schools, and practiced in maneuvers. The word itself had appeared now and then in German military writing since the mid-1930s, not in a specific sense but to refer to the kind of quick, complete victory that was at the heart of the army’s operational planning, and a central feature of its doctrine and training. Nor was the context always positive. Just before the outbreak of war, one critic affirmed that the chances of a blitzkrieg victory against an evenly matched enemy were zero.

To say that blitzkrieg was an ex post facto construction nevertheless makes as much sense as to assemble the components of a watch, shake the pieces in a sack, and expect to pull out a functioning timepiece. The most reasonable approach involves splitting the difference. On one hand, blitzkrieg is a manifestation of Bewegungskrieg, the war of movement, the historic focus of Prussian/German strategic and operational planning that Seeckt and his contemporaries sought to restore after the Great War. On the other hand, blitzkrieg gave a technologically based literalness to an abstract concept. Bewegungskrieg had always been more of an intellectual construction than a physical reality. It involved forcing an enemy off balance through sophisticated planning creatively implemented in a context of forces moving essentially at the same pace. In blitzkrieg the combination of radios and engines made it possible for an army literally to run rings around its enemy—if, and it was a big if, its moral and intellectual qualities were on par with its material.

The Polish campaign helped shape that concept. Considered in hindsight, Case White, the cover name for the invasion of Poland, seems a classic example of what the Germans call “a made bed.” Much of the terrain was ideal for mobile operations: large stretches of open country with neither formidable natural obstacles nor man-made ones like the hedgerows of Normandy. The weather cooperated. September was unusually dry—a boon in a country where paved roads were few to an invader whose off-road capacities were limited. The Polish army depended on the muscles of men and horses for mobility. It had around 600 tanks, but most of them were counterparts of the Panzer I, and most of those were attached by companies to the cavalry brigades. Strategically, German occupation of the rump state of Slovakia left Poland enveloped on three sides—yet the Polish army was deployed along its frontiers in a pattern similar to the one Napoleon sarcastically suggested was best suited to stop smuggling.

That positioning reflected domestic factors. Poland, much like West Germany during the Cold War, could not afford to abandon large parts of its territory without devastating consequences for the national morale on which its conscript army’s effectiveness depended. It reflected as well the defensible—and accurate—conclusion that even without the non-aggression pact with Germany, whose negotiation had hardly been a secret, the Soviet Union could be expected to seek direct profit from a German- Polish war.

In sum, Poland had no prospects of waging anything like a long war successfully. Its only prospects lay with its French and British allies. That, in turn, ironically placed Poland in a position similar to that of Prussia in the autumn of 1806, when it did not have to defeat Napoleon, just bloody his nose and set him back on his heels until the British guin eas and Russian bayonets that were the Fourth Coalition’s real strengths could be brought into play. German planners, with vivid memories of the World War I blockade and well aware of France’s “Anaconda plan” of total mobilization for total war, were correspondingly committed to a war from a standing start. Overwhelming Poland as quickly as possible would change the military dynamic—and might just change the international dynamic as well, if Hitler could pull off another of his high-wire stunts.

Reduced to basics, the “decisive point” of Case White rested with Army Group South: three armies coming out of Silesia and Slovakia. Army Group North’s two armies attacked from Pomerania and East Prussia. The strategic intention was a breakthrough of the Polish cordon followed by a double penetration: a pincers movement on a Schlieffe nesque scale, the tanks meeting somewhere around Warsaw and then separating again, one part turning inward toward the Vistula River to finish off the trapped Polish main force, the other continuing to the Bug River to screen the decisive battle and secure against such contingencies as Soviet treachery.

The projected campaign generally resembled pre-World War I planning and specifically replicated the Austro-German offensive into Russian Poland in October 1914. Despite significant tactical successes, that operation ultimately failed. There was only one way for the German army to achieve its objective operationally: keep moving. Army Group South had the peacetime army’s three mobile corps headquarters, four panzer divisions, all four of the light divisions, and two motorized divisions—around 2,000 tanks. Army Group North had the newly organized 10th Panzer Division, a provisional division built around a panzer brigade, and a corps of one panzer and two motorized divisions under Heinz Guderian—around 500 tanks, but with lesser distances to cover.

Army Group South broke through and drove northeast, bypassing defenses, striking into the Poles’ rear to cut communications and block retreats, supported by Stuka dive-bombers whose precision strikes were neither disrupted from the air nor challenged from the ground. The Stukas had increased their repertoire by adding a propeller-driven siren to each strut of their fixed landing gear. The eldritch screaming of these “Trumpets of Jericho” reinforced the conviction, affirmed by virtually everyone ever under dive-bomber attack anywhere, that the plane was aiming at him personally.

That did not mean the Poles collapsed. Nor did they act, contrary to one report, as though German tanks were still made of wood and cardboard. The panzers and motorized infantry of Army Group North found breaking out was hard to do against local counterattacks and the determined resistance of cut-off troops with no place to go. It was in this sector that the legend of cavalry attacking tanks with lances was born—courtesy of some Italian journalists who listened to shaken German survivors of the actual event. On September 1, a Polish lancer regiment stumbled on elements of a German battalion in a clearing, charged, and took them by surprise. Then a few German armored cars appeared and shot the lancers to pieces. But that incident, among others, shook the 2nd Motorized Division badly enough that its commander briefly considered retreat until brought up short and sharp by Guderian.

The panzers’ initial fighting in the northern sector featured the kinds of logistical, tactical, and communications lapses predictable for any untested formations in the first days of any war. Guderian’s lead-from-the-front approach led to interventions in the chain of command that confused his subordinates. Nevertheless, by day five of the offensive the tanks and trucks of Army Group North were on their way to Warsaw. Hitler himself came forward to see the results, and the one-time infantryman was suitably impressed when Guderian showed him Polish artillery positions overrun and destroyed by tanks.

On October 15 the spearheads of XIX Panzer Corps, now reinforced by the 10th Panzer Division, reached Brest-Litovsk, far into the Polish rear. Army Group South’s 4th Panzer Division reached the outskirts of Warsaw as early as October 8, but lost half its tanks attempting to break into the city. The general advance was further delayed by a desperate Polish breakout attempt that caught the German left flank along the Bzura River. But the panzers shifted their axis of advance 180 degrees in twenty-four hours with an ease belying their lack of experience. Stukas and conventional bombers hammered Polish concentrations. The counterattack collapsed in a welter of blood and the mobile forces swung back toward Warsaw to link up with Guderian.

On September 17, the Red Army crossed Poland’s eastern border with a half million troops. That ended any Polish hopes for continued resistance on the far side of the Vistula—hopes in any case dashed by the refusal of the Western allies to make more than a token effort to relieve the German pressure. Only Warsaw remained unconquered and its defenders cashed out high, inflicting heavy casualties despite continuous air and artillery bombardment, both characterized by disturbingly high levels of inaccuracy. German propaganda spoke of an eighteen-day war. Army Group South, which bore the brunt of the fight for Warsaw, lost more men in the second half of the campaign than in the first two weeks, a dry run for the serious work. Warsaw capitulated on September 27. On October 5, Hitler reviewed a victory parade through the devastated city. The last organized Polish force fought off the 13th Motorized Division for four days before surrendering at Kock on October 6. Poland was kaput. What remained was establishing the new border with Russia, organizing the occupation of the Reich’s latest conquest, and evaluating performances.

To a degree, unusual after such a decisive victory, the German army applied an “iron broom” to doctrine, training, and command. The artillery was criticized for hanging too far back and for being unresponsive to the rapidly changing requirement of modern battle. The infantry came under fire for a general lack of aggressiveness and flexibility and for too often waiting for the guns, the tanks, and the Stukas to do the work instead of pressing forward with their own resources. Officers at all levels were reminded of the need for maintaining situational awareness, for maintaining calm in what seemed a crisis, and, above all, for seizing the initiative in every situation.

The panzers came off unscathed by comparison. Prior to September 1, questions had remained as to how well the methods and material of mobile warfare would actually work in the field. A month later, there seemed no doubt: The combination of tanks, motorized troops, and aircraft could not only break into and break through an enemy front; they could break out, with decisive effect. Breaking regiments and battalions into combined-arms battle groups, usually based on the tank and rifle regiments but reconfigured to meet changing tactical and operational situations, was generally validated. The difficulties of practical implementation even against what quickly became episodic resistance were noted, but described as susceptible to training and experience.

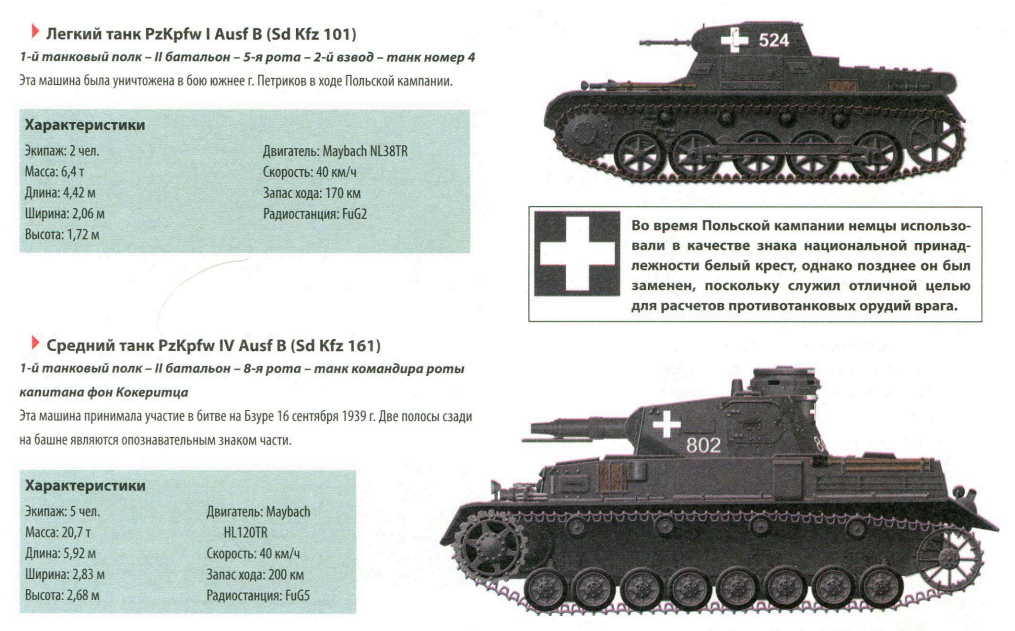

That did not mean fine-tuning could be neglected. The armored force reported a loss of just over 200 tanks—under 10 percent of the total committed, and that figure is the one most often cited. Recent research by Polish scholars in German records indicates that almost 700 tanks were written off at one time or another from all causes. About 550 of those were either total losses or beyond the ability of unit workshops to repair. These statistics reflect a demanding operational environment, one that encouraged neglecting vehicle maintenance because of crew and unit stress and fatigue. They reflected the relative fragility of the Panzer Is and IIs that formed the bulk of the armored force. And they reflected the determined local fights, often to the last man, made by Polish troops using everything from satchel charges, grenades, and antitank rifles to field guns firing over open sights, in the pattern of the First World War.

In the long run, actual losses were inconsequential. No one with any responsibility seriously considered the light tanks as anything but stopgaps. On mobilization, each tank battalion had left one company behind as a depot. In the panzer divisions, one of the remaining three companies was supposed to be equipped with Panzer IIIs and IVs. Delivery problems meant only the 1st and 5th Divisions came close to that standard. The light tanks were left on their own—contrary to prewar doctrine and expectation. Absent projected support from the high-velocity gun of the Panzer III and the 75mm of the Panzer IV, light tanks depended even more than anticipated on speed and maneuverability. A light tank halted for any reason was wearing a bull’s-eye. A light tank challenging a barricade risked winding up on its side. A light tank engaging antitank guns was pitting hope against experience. It was first-rate crew training—but the hard way.

Tactically, frontline reports uniformly insisted on using tanks en masse, by battalions at least. Even when needed for direct support of infantry, tanks should never be distributed in less than company strength. Panzer officers also consistently complained of the motorized infantry’s inability to keep pace, and more or less delicately suggested that advancing under fire was not a particular strong point. Some suggestion of the infantry’s problems in that regard comes from the war diary of the 35th Panzer Regiment. Describing the initial fight for Warsaw on September 9, it refers to truck-borne infantry taking cover under heavy small- arms fire as their unarmored vehicles went up in flames. The diary does not refer to any direct support provided by tanks that were having their own troubles that day. “Avoid built-up areas” was solid panzer advice, eventually forgotten in the rubble of Stalingrad. Solid as well was the recognition that the motorized troops at least needed more in the way of organic supporting weapons and, if possible, a general issue of armored half-tracks.

The panzers took with them into Poland another legacy. After 1933, generalized concepts of the “East” as an object of German manifest destiny, long present in the general culture, were integrated with National Socialist conceptions of the East as “living space.” Soldiers were informed that they were the vanguard of Germany’s destiny, with the missions of conquering the new territory and governing the primitives who inhabited it. “I’m looking for hard men,” Hitler declared to his adjunct. “I need fanatical National Socialists. See to it that such men are brought forward.”

The Führer had plenty of prototypes. From the early days of September 1939, negative, derogatory attitudes toward Poles and Jews informed the army’s official reports, its private correspondence, and its public behavior. Troops used Nazi jargon to describe the people as “subhuman” or “inhuman”; junior officers and enlisted men showed consistent willingness to initiate reprisals, to implement terror, to translate vague authorizations to establish local security into fists and boots, summary executions and firing squads.

The Prussian/German army had a history—it might be said a culture—based on risk and violence, fear and force. World War I had shown German units were likely to assume any surprise attack was initiated by the civilians. A report from 4th Panzer Regiment, for example, describes priests “disappearing” into a village church “as soon as panzers appeared. . . . Signals were immediately observed from the church tower. Then machine guns opened fire on us.” Two well-placed rounds from a Panzer IV solved that particular tactical problem. The social/ cultural one remained. Fast-moving armored formations were disproportionately likely to come under unexpected fire. Erich Hoepner, commanding XVI Panzer Corps, ordered “the most severe measures” against “partisans.” On September 4 and 5, troops of his 1st Panzer Division responded by shooting a number of male civilians, apparently in the belief that someone in the village had fired on them. Elements of 1st Panzer killed more civilian men and destroyed as many as 80 farms in another village in reprisal for a Polish counterattack—presumably assuming the civilians had somehow participated. In the aftermath of the collapse of the Bzura counterattack pocket, the 4th Panzer Division was involved in a number of killings of Polish civilians and of soldiers who were legally prisoners of war by the terms of the local surrender.

Examples can be multiplied, though not yet ad libitum. Compared to the rear-echelon “Action Groups” that followed the army, and to a Waffen SS that was at this stage far more dangerous to civilians than to anyone with a gun, the panzers’ shield might even be described as relatively clean. Their behavior nevertheless went well beyond first-battle jitters involving quick triggers or misunderstood gestures or a straggling soldier officially surrendered who still had his rifle.