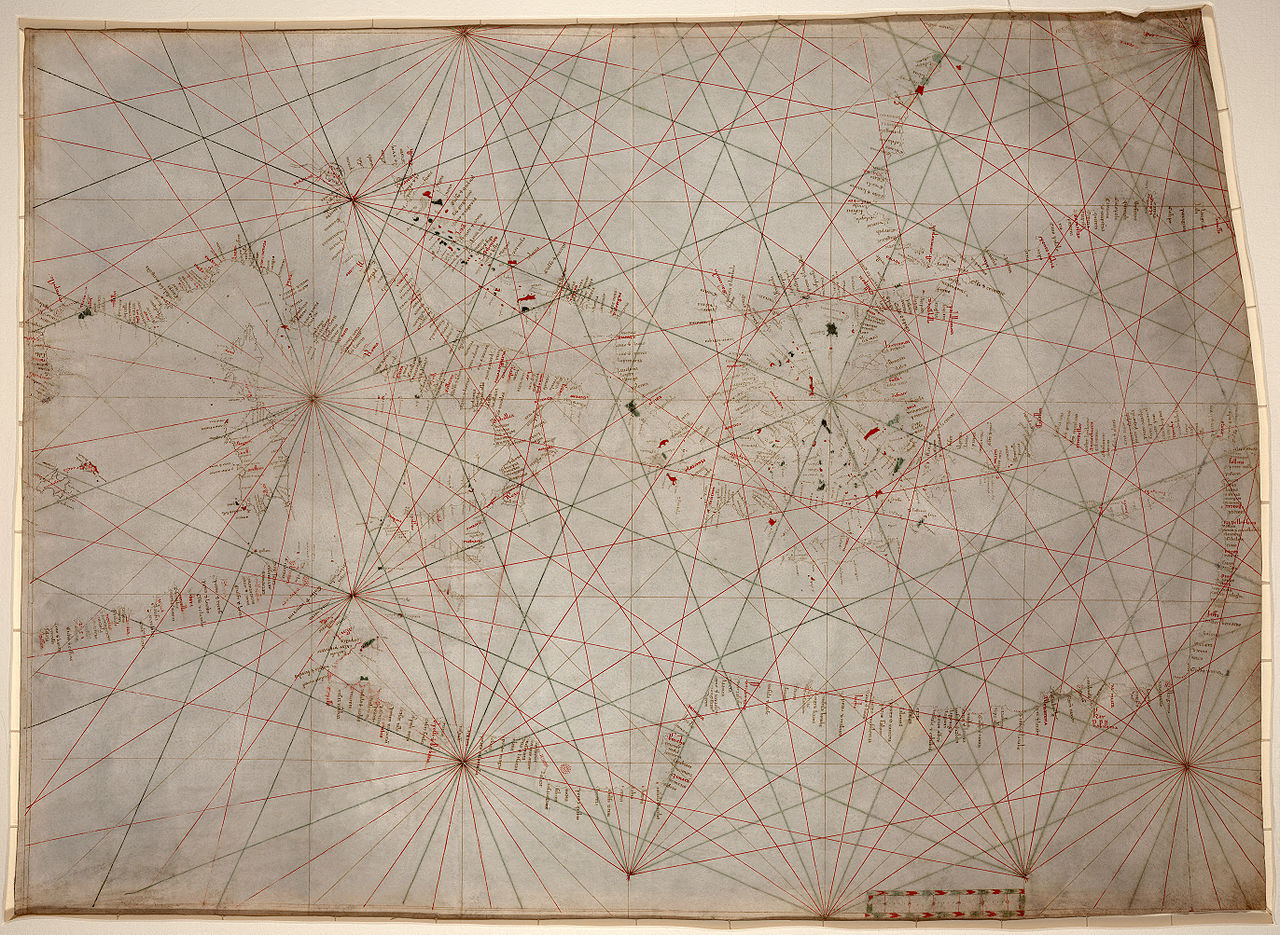

The oldest original cartographic artifact in the Library of Congress: a portolan nautical chart of the Mediterranean Sea. Second quarter of the 14th century.

In view of the dearth of useful technical aids it is hard to resist the impression that navigators relied on the sheer accumulation of practical craftsmanship and lore to guide them in unknown waters. From the thirteenth century onwards, compilers of navigational manuals distilled vicarious experience into sailing directions which could genuinely assist a navigator without much prior local knowledge. ‘Portolan charts’ began to present similar information in graphic form at about the same period. The earliest clear reference is to the chart which accompanied St Louis on his crusade to Tunis in 1270.

At the start of our period, there were marked technical differences between Mediterranean and Atlantic Europe in shipbuilding. In both areas, the shipwright’s was a numinous craft, sanctified by the sacred images in which ships were associated in the pictorial imaginations of the time: the ark of salvation, the storm-tossed barque, and the ship of fools. Much of our knowledge of medieval shipyards comes from pictures of Noah. Underlain by this conceptual continuity were differences in technique which arose from differences in the environment. Atlantic and northern shipwrights built for heavier seas. Durability was their main criterion. They characteristically built up their hulls plank by plank, laying planks to overlap along their entire length and fitting them together with nails. The Mediterranean tradition preferred to work frame-first: planks were nailed to the frame and laid edge-to-edge. The latter method was more economical. It demanded less wood in all and far fewer nails; once the frame was built, most of the rest of the work could be entrusted to less specialized labour. In partial consequence, frame-first construction gradually spread all over Europe until by the end of our period it was the normal method everywhere. For warships, however, Atlantic-side shipyards generally remained willing to invest in the robust effect of overlapping planks, even though, from the early fifteenth century, these were invariably attached to skeleton frames.

Warships—in the sense of ships designed for battle—were relatively rare. Warfare demanded more troop transports and supply vessels than floating battle-stations and, in any case, merchant ships could be adapted for fighting whenever the need arose. In times of conflict, therefore, shipping of every kind was impressed: availability was more important than suitability. Navies were scraped together by means of ship-levying powers on maritime communities, which compounded for taxes with ships; or they were bought or hired—crews and all—on the international market.

Until late-medieval developments in rigging improved ships’ manoeuvrability under sail, oared vessels were essential for warfare in normal weather conditions. Byzantine dromons were rowed in battle from the lower deck, as shown in this late eleventh-century illustration, with the upper deck cleared for action, apart from the tiller at the stern.

Maritime states usually had some warships permanently at their disposal, for even in time of peace coasts had to be patrolled and customs duties enforced. Purpose-built warships also existed in private hands, commissioned by individuals with piracy in mind, and could be appropriated by the state in wartime. From 1104, the Venetian state maintained the famous arsenal—over 30 hectares of shipyards by the sixteenth century. From 1284 the rulers of the Arago-Catalan state had their own yard, specializing in war galleys, at Barcelona, where the eight parallel aisles built for Pere III in 1378 can still be seen. From 1294 to 1418 the French crown had its Clos des Galées in Rouen, which employed, at its height, sixty-four carpenters and twenty-three caulkers, along with oar-makers, sawyers, sail-makers, stitchers, rope-walkers, lightermen, and warehousemen. Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy from 1419 to 1467, whose wars and crusading projects created exceptional demand for shipping, founded a shipyard of his own in Bruges, staffed by Portuguese technicians. England had no royal shipyard, but Henry V maintained purpose-built ships of his own as well as borrowing them from others: an ex-pirate vessel, the Craccher, was for instance loaned by John Hawley of Dartmouth. Such loans were not acts of generosity: Henry V was one of the few monarchs of the European middle ages who were serious about curtailing their own subjects’ piracy.

At the start of our period, warships, whether on the Atlantic-side or Mediterranean-side of Europe, were almost invariably driven by oars. Rigging was light by modern standards and only oars could provide the manoeuvrability demanded in battle, or keep a vessel safe in the locations, often close to the shore, where battles commonly took place.

Gradually, however, oars were replaced by sails, especially on the Atlantic seaboard. With additional masts and more sails of differing size and shapes, ships could be controlled almost as well as by oars, while frame-first construction permitted rudders to be fitted to stern-posts rising from the keel: formerly, ships were steered by tillers dangled from the starboard towards the stern. These improvements in manoeuvrability, which were introduced gradually from the twelfth century onwards, freed ships from the economic and logistic burden of vast crews of oarsmen. Oar-power dominated Baltic warfare until 1210, when the crusading order of Sword-brothers switched to sail-driven cogs, which helped them extend their control along the whole coast of Livonia. King John of England had forty-five galleys in 1204 and built twenty more between 1209 and 1212. Edward I’s order for a battle fleet in 1294 was for twenty galleys of 120 oars each. A hundred years later, however, only small oared craft formed part of England’s navy, in which the fighting vanguard was entirely sail-driven. French shipbuilding changed faster. The French at Sluys in 1340 had 170 sailing ships as well as the royal galleys: many of them were certainly intended for the fray.

To a lesser extent, the oar-less craft played a growing role in Mediterranean warfare, too. The Florentine chronicler, Giovanni Villani, with characteristic exaggeration, dated the start of this innovation to 1304 when pirates from Gascony invaded the Mediterranean with ships so impressive that ‘henceforth Genoese, Venetians and Catalans began to use cogs. . . . This was a great change for our navy.’ In the fifteenth century, the Venetian state commissioned large sailing warships specifically for operations against corsair galleys.

Once free of oar-power, ships could be built higher, with corresponding advantages in battle for hurlers of missiles and intimidators of the foe: the tactics favoured throughout the period made height a critical source of advantage. To hoist tubs full of archers to the masthead was an old Byzantine trick, which Venetian galley-masters adopted. Rickety superstructures, which came to be known as ‘castles’, cluttered the prows of ships; shipwrights strained to add height even at the risk of making vessels top-heavy. The clearest demonstration of the advantages of height is in the record of sailing-ships in combat with galleys: countless engagements demonstrated that it was virtually impossible for oar-driven craft to capture tall vessels, even with huge advantages in numbers—like those of the reputed 150 Turkish boats that swarmed ineffectively round four Christian sailing ships in the Bosphorus during the siege of Constantinople of 1453, or the score of Genoese craft that hopelessly hounded the big Venetian merchantman, the Rocafortis, across the Aegean in 1264.

In the Mediterranean, galleys tended to get faster. The Catalan galleys of the late thirteenth century, at the time of the conquest of Sicily, had between 100 and 150 oars; by the mid-fourteenth century, complements of between 170 and 200 oars were not unusual, while the dimensions of the vessels had not grown significantly. Light galleys pursued and pinned down the foe while more heavily armed vessels followed to decide the action. The oarsmen had to be heavily armoured, with cuirasse, collar, helmet, and shield. Despite their place in the popular imagination, ‘galley slaves’ or prisoners condemned to the oar were never numerous and were rarely relied on in war. Oarsmen were professionals who doubled as fighters; once battle was joined, speed could be sacrificed in favour of battle strength and up to a third of the oarsmen could become fighters.

The Tactical Pattern

Deliberately to sink an enemy ship would have appeared shockingly wasteful. The use of divers to hole enemy ships below the waterline was known and recommended by theorists but seems to have been rarely practised. For the object of battle was to capture the enemy’s vessels. At Sluys, as many as 190 French ships were said to have been captured; none sank—though so many lives were lost that the chronicler Froissart reckoned the king saved 200,000 florins in wages. Vessels might, of course, be lost in battle through uncontrollable fire, or irremediably holed by excessive zeal in ramming, or scuttled after capture if unseaworthy or if the victors could not man them.

Ships fought at close quarters with short-range missiles, then grappled or rammed for boarding. The first objectives of an encounter were blinding with lime, battering with stones, and burning with ‘Greek fire’—a lost recipe of medieval technology, inextinguishable in water. A digest of naval tactics from ancient treatises, compiled for Philip IV of France, recommended opening the engagement by flinging pots of pitch, sulphur, resin, and oil onto the enemy’s decks to assist combustion. It was a blast of lime, borne on the wind, that overpowered the crew of the ship carrying the siege train of Prince Louis of France to England in February 1217. Protection against lime and stones was supplied chiefly by stringing nets above the defenders; flame-throwers could be resisted, it was said, by felt soaked in vinegar or urine and spread across the decks. In a defensive role, or to force ships out of harbour, fire ships might be used, as they were—to great effect—by Castilian galleys at La Rochelle in June 1372, when blazing boats were towed into the midst of the English fleet.

‘Greek fire’ was ignited by a substance, combustible in water, of which the recipe is lost. Together with short-range missiles and blasts of blinding lime and fire-bombs, it was used prior to boarding, to distract the enemy crew and cripple rather than destroy the ship. Normally, a hand-held siphon with a bronze tube at the prow was used to project it.

As the ships closed, crossbowmen were the decisive arm. According to the chauvinistic Catalan chronicler of the fourteenth century, Ramon Muntaner, ‘The Catalans learn about it with their mother’s milk and the other people in the world do not. Therefore the Catalans are the sovereign crossbowmen of the world. . . . Like the stone thrown by a war machine, nothing fails them.’ Catalan proficiency in archery was supported by special tactics. When Pere II’s fleet confronted that of Charles of Anjou off Malta in September 1283, the Catalans were ordered by message ‘passed from ship to ship’ to withstand the enemy missiles with their shields and not to respond except with archery. The outcome, according to the chronicle tradition, was that 4,500 French were taken prisoner.

At close quarters, Philip IV’s digest recommended a range of devices: ripping the enemy’s sails with arrows specially fitted with long points, spraying his decks with slippery soap, cutting his ropes with scythes, ramming with a heavy beam, fortified with iron tips and swung from the height of the mainmast, and, ‘if he is weaker than you, grappling.’ Ramming or grappling was the prelude to an even closer-fought fight with missiles followed by boarding.

As far as is known from a few surviving inventories, the weapons carried on board ships reflected more or less this range of tactics. When inventoried in 1416, Henry V’s biggest ship had seven breech-loading guns, twenty bows, over 100 spears, 60 sail-ripping darts, crane-lines for winching weaponry between fighting decks, and grapnels with chains twelve fathoms long. It must not be supposed that the inventory was complete as most equipment was surely not stowed aboard, but it is probably a representative selection. Artillery detonated by gunpowder came into use during the period, but only as a supplement to existing weaponry, within the framework of traditional tactics. Numbers of guns increased massively in the fifteenth century, though it is not clear that they grew in effectiveness or influenced tactics much. Overwhelmingly, they were short-range, small-calibre, swivel-mounted breechloaders; anti-personnel weapons, not ship-smashers.