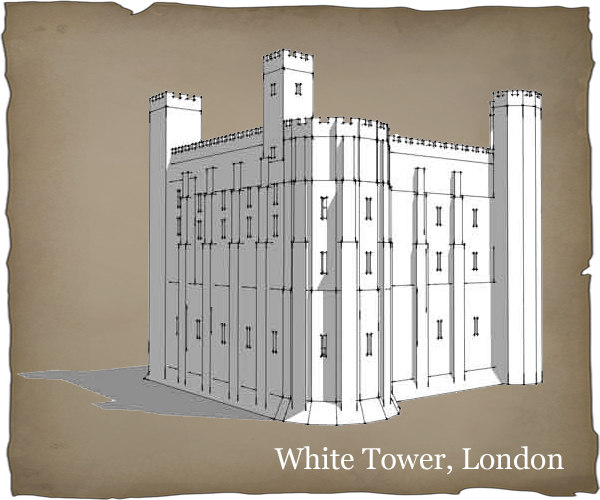

Illustration of how the Tower may have looked, c1300 by Ivan Lapper.

Moving slowly, and savagely stamping out sparks of resistance as he went, William took until mid-December to reach Southwark on the south bank of the Thames. He found the wooden London Bridge – the only river crossing – barred against him. Cautiously, he marched west, burning and looting, until at Wallingford he met a submissive Archbishop of Canterbury, Stigand, sent by the Witan to offer him the crown. On Christmas Day 1066, William I was crowned by Stigand in Edward the Confessor’s newly built Westminster Abbey.

Outside the abbey, the coronation ceremony was disrupted by angry Londoners loudly opposing their new, foreign-born king. Alarmed, Norman soldiers rushed from the abbey with drawn swords. It was a reminder that their conquest was far from complete. They were a tiny, beleaguered army amidst a hostile, barely cowed populace which bitterly resented these strangers with their weird tongue and alien ways. The Normans had killed the English king and decimated his host, but to enjoy the fruits of victory they realised they must be equally ruthless in repressing Harold’s discontented former subjects. And they had a tried and tested method at their disposal: the castle.

Fortified hilltops had been commonplace in England for centuries; as the ramparts and ditches of Dorset’s Maiden Castle, dug by the ancient British, attest. The Romans had their fortresses too, as the stones of Hadrian’s Wall bear witness. But it was the Normans who patented the ‘motte-and-bailey’ castle. The idea was simple. Where there was no convenient natural hill, as with a sandcastle, the Normans threw up an artificial mound – the motte – crowned by a wooden tower. They then dug a defensive ditch – the bailey – around its base, using the excavated earth to make an additional encircling rampart, surmounted by a wooden fence. By 1066 the Normans were past masters at the speedy construction of these flat-pack fortresses – they could build one within a week – and their first acts upon landing had been to put up two, at Pevensey and Hastings.

Eventually, the Normans would build some eighty-four motte-and-bailey castles across their newly conquered kingdom. The early ones were sited near their Sussex beachhead – Lewes, Bramber and Arundel – guarding strategic river valleys in case they needed to retreat to the coast in a hurry. The temporary wooden castles were soon replaced by solid stone, once the Normans felt confident that they were in England for good. The functions of the castle were twofold: as the imposing home and headquarters of the local magnate; and as a refuge for his loyal soldiers, servants and tenants in times of trouble. They were the nodal points of the feudal mesh of occupation that the Normans threw over the conquered kingdom.

William rewarded the knights who had followed and fought alongside him with large parcels of conquered English land – together with the overlordship of the peasants who tilled the soil. Great castles were erected at Dover, Exeter, York, Nottingham, Durham, Lincoln, Huntingdon, Cambridge and Colchester. Norman names – de Warenne, de Lacey, Beauchamp – replaced Saxon ones in the nobility and clergy as a military occupation morphed into a new social structure.

William lavished special care on one castle in particular. His new capital, London, was vulnerable to attack on its eastern, seaward side. It clearly needed the protection that only a great castle could provide. England’s earlier military masters, the Romans, had pointed the way. In the fourth century AD, to defend the port-city they called Londinium Augusta, they had thrown up a stout city wall. It ran north–south from today’s Bishopsgate down to the Thames before swinging west along the northern bank of the river. Only the foundations of the wall remained by William’s time, but it was in the angle of its south-eastern corner, on the site of a former Roman fort named Arx Palatina – erroneously thought by the Normans (and by Shakespeare) to have been put up by Julius Caesar – that William decided to build his super-castle.

The rowdy scenes at his coronation had made it very clear that Norman rule could only be imposed by brute force. As a contemporary French chronicler, William of Poitiers, recorded, ‘Certain strongholds were made in the town against the fickleness of the vast and fierce populace.’ A fortress to house London’s garrison and intimidate its inhabitants – who totalled around 10,000 in 1066 – had to be constructed without delay. Within days of the Christmas coronation, conscripted gangs of Saxon labourers were hacking into the frozen soil. The remains of the Roman city wall served as a temporary barrier on the new fortress’s eastern and southern sides. A wide and deep ditch, surmounted by a palisaded rampart, went up on the western and northern sides of the site. A wooden tower was erected within three days in the middle of this rough rectangle. After a decade, however, largely spent in stamping out rebellions in the west and north of his new kingdom, William decided to remake his temporary timber structure in permanent stone.

William had the very man in mind to realise his vision. He envisaged the building of a mighty edifice that would be at once fortress and palace – the last word in state-of-the-art military architecture, as well as an impressive royal residence. A towering, solid structure that would literally set Norman superiority in stone, inducing a Saxon cultural cringe and snuffing out any notion of further resistance to his rule. The master architect that William hand-picked to oversee the project was a talented cleric named Gundulf.

Born in 1024 near Caen, Gundulf, like many medieval bright lads, entered the all-powerful Church. Legend says his decision was prompted by his miraculously surviving a storm during a perilous pilgrimage to Jerusalem in the 1050s. He became a protégé of Lanfranc, the Italian-born prior of the great Benedictine Bec Abbey. Gundulf demonstrated a particular talent for architecture, designing churches and castles. He was an emotional man, given to outbursts of weeping, which won him the disrespectful nickname ‘the Wailing Monk’. Nevertheless, when William sacked the Saxon Stigand and chose Lanfranc to succeed him as the first Norman Archbishop of Canterbury in 1070, the new archbishop brought his temperamental clerk with him to Canterbury, where Gundulf supervised extensions to the cathedral.

The castle-building cleric caught the Conqueror’s eye, and Gundulf was soon summoned to London. William suggested that Gundulf should crown his architectural career by building in London the greatest castle in all Christendom. Gundulf was reluctant. Ageing and increasingly pious, he told the king that in his time left on earth he wanted to construct an ecclesiastical, rather than a secular, edifice – if possible a cathedral. No problem, William replied. At Rochester, near Canterbury, there already was a cathedral, in ruins since being pillaged in a Viking raid. He offered Gundulf the vacant bishopric and money for the cathedral’s restoration – so long as he built the great London castle first. So – doubtless with more tears and fears – Gundulf accepted his commission. In 1077 he became Bishop of Rochester, and the following year – 1078 – work on London’s new Tower commenced.

Gundulf set about his task with vigour. He was fifty-four, old by medieval standards, yet would not only complete both the White Tower and Rochester Cathedral (along with a fine new castle there), but also see out both the Conqueror, and William’s son and successor, William Rufus. The White Tower gained its name from the blocks of pale marble-like Caen stone imported from Normandy with which it was constructed – with infill of local coarse Kentish ragstone – and from the coats of gleaming whitewash with which it was eventually plastered. The Tower was a huge structure, the biggest non-ecclesiastical building in England, rising some ninety feet above ground, with four pepperpot turrets, one at each corner. All the turrets were rectangular, with the exception of the north-east one, which was rounded to contain a spiral staircase.

When complete, the White Tower measured 107 feet (33 metres) from east to west, and 118 feet (36.3 metres) from north to south. The massive walls were fifteen-foot thick at their base, tapering to eleven at the top, built on foundations of chalk and flint. An undercroft, or basement, formed the lowest floor of the White Tower, where a well was sunk to supply the inhabitants with water. The cellar vaults were used at first for storing food and drink, as well as arms and armour. A more sinister function was their later use as the Tower’s principal torture chambers, the agonised screams of victims muffled by the surrounding earth and stone. The main, middle floor was entered, then as now, on the south side by an exterior wooden staircase, which could be quickly removed in case of siege. This floor was originally the living quarters of the Tower’s garrison, and was divided into three vast rooms: a refectory with a great stone fireplace where the soldiers ate and made merry when off duty; a smaller dormitory with another fireplace where they slept; and, in the south-east corner, the beautifully simple Romanesque Chapel of St John, with its twelve huge pillars.

The second floor of the White Tower was reserved for the use of the constable – the Tower’s commander appointed by the monarch – for important guests, and eventually for state prisoners of high status. The rooms consisted of a great hall complete with fireplace – used for state banquets – with a minstrels’ gallery running around it; and the constable’s chamber, a space which served as bedroom, meeting room and living quarters for the Tower’s top official. Each floor had latrines with chutes into underground cesspits emptied by the ‘night soil men’.

South of the White Tower, a gaggle of smaller buildings sprang up to serve Gundulf’s great structure. These, the first of many additions and extensions added to the original keep across the centuries, were temporary structures not designed to last. There were stables, blacksmiths’ forges, stores for building materials, chicken coops and pigsties. Before he died, Gundulf oversaw the building of a high curtain wall guarding the Tower on its southern, river side, and the first of many smaller towers girding the great central keep. It is not known exactly when the oldest surviving tower outside the White Tower, the Wardrobe Tower, was built; and the date of the construction of the royal palace south of the White Tower is equally uncertain. It is likely, however, that by the time of Gundulf’s death, aged eighty-four, in 1108, a start had been made.

Gundulf had long outlived his original patron. Having finally subdued the English, William the Conqueror was faced with rebellion in his native Normandy by his own oldest son, Robert Curthose. It was on a punitive expedition against the rebellious town of Mantes, in 1087, that the Conqueror, his youthful stockiness run to fat, met his end. Having torched the conquered town with his customary savagery, William was riding through the blazing streets when his horse stepped on a burning ember. The beast bucked violently, throwing William’s great gut against the hard iron saddle pommel, and causing devastating internal injuries to his swollen stomach. William took ten days to die in agony. Feared more than loved, when he expired, his remaining followers stripped his bloated corpse and then scarpered. The Conqueror’s final indignity came at his funeral, when monks attempted to stuff his carcase into a small sarcophagus. The cadaver split, filling the church with such a noxious stench that mourners fled. It was an inglorious end for the victor of Hastings and the founder of the Tower.